After marrying Jeannette "Johnny" Allen, the high-spirited daughter of Major General Henry Tureman Allen, in 1914, her husband gained entrée into elite inner circles of Washington society and within the military. They were the parents of three children: Josephine (1914-1977), Allen (1917-2008), and Jean (b. 1923).

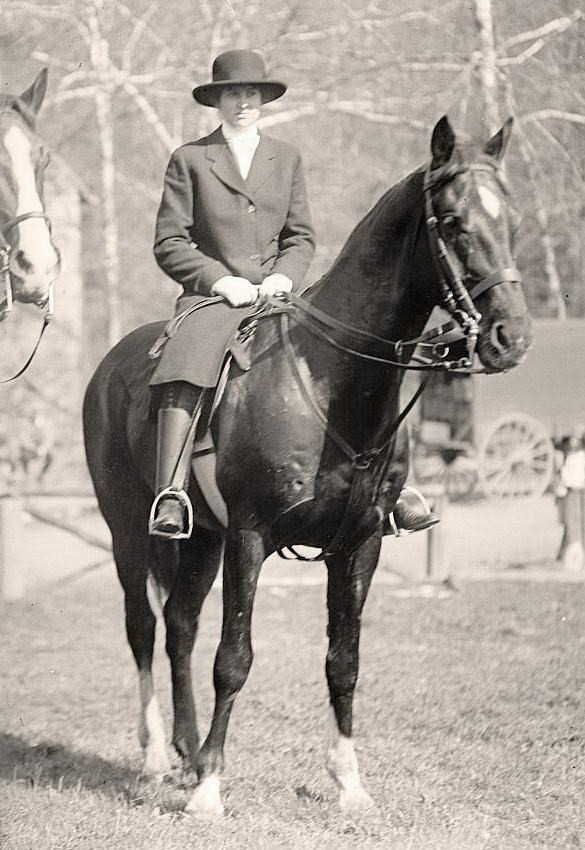

Like many other cavalrymen, her future husband, Frank Maxwell Andrews, became an ardent and hard-riding polo player. After being detailed to Ft. Ethan Allen in Vermont in December 1913, he met Jeanette Allen, the daughter of General Henry T. Allen. She not only liked horses and polo but she also played polo with Army teams. Even though General Allen is reported to have said that no daughter of his would ever marry an aviator, Andrews became interested in flying during their courtship. But he bided his time and won her hand. They were married on March 18, 1914 and three children were later born to them: Josephine, Allen and Jean.

A story related in the press many times during Andrews' lifetime claimed that General Allen forestalled the aeronautical aspirations of his future son-in-law by declaring, as stated above, that no daughter of his would marry a flyer. Andrews' service records, however, show that his commanding officer in the Second Cavalry vetoed his application for temporary aeronautical duty with the Army Signal Corps in February 1914, a decision that held firm despite a plea from the Chief Signal Officer's for reconsideration by higher-ups.

Jeannette's husband was commander of all Forces in Europe during the early stages of World War II, serving with General Dwight D. Eisenhower at times, and when Eisenhower was appointed to command all allied forces in Europe, Andrews succeeded him as commander of US forces. Two months later in May 3, 1943, he was killed in the crash of a B-24 in Iceland.* Before his premature death in 1943, Frank Maxwell Andrews played a major role in building the small US Army Air Corps of the 1930s into the powerful US Army Air Forces of World War II. Furthermore, he had become one of the key military commanders in the United States' armed forces.

[* Only the tail gunner, S/Sgt. George A. Eisel of Columbus, Ohio, survived.]

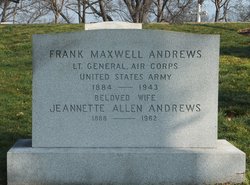

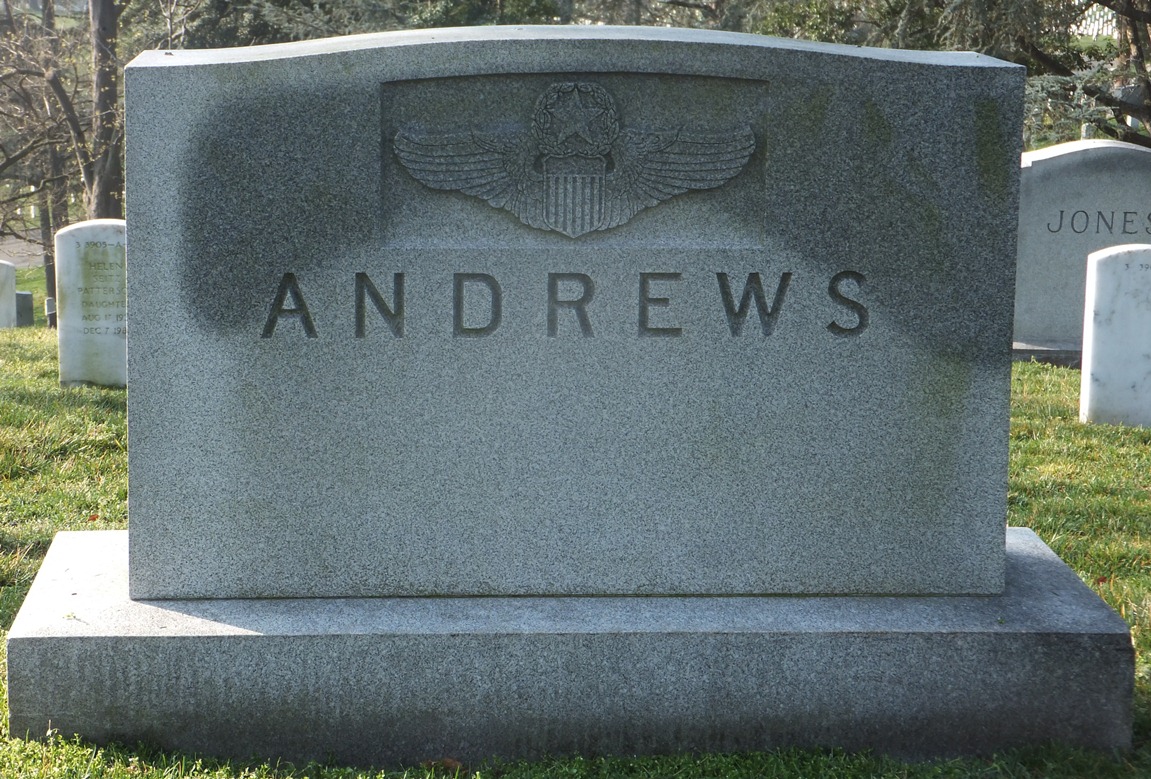

U.S. Veterans Gravesites, ca. 1775-2006

Name: Jeannette Allen Andrews

Service Info.: AR United States Army

Birth Date: 28 Apr 1889

Death Date: 19 Sep 1962

Relation: Wife of Veteran

Interment Date: 20 Sep 1962

Cemetery: Arlington National Cemetery

Cemetery Address: C/O Director Arlington, VA 22211

Buried At: Section 2 Site 1883-A

Her husband was an outspoken proponent of air power and Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland is named in his honor. Jeanette Allen Andrews, the wife of Frank Maxwell Andrews is buried with her husband in Section 3 of Arlington National Cemetery.

Remembering Frank Andrews

by Dr. Henry O. Malone

Former Army Historian 02/28/02 - HAMPTON, Va. (AFPN)

- For decades, Andrews Air Force Base, Md., has been the "gateway to the capital" for presidents and foreign leaders. Today, it is far more famous than the person for whom it was named. Most are unaware that Lt. Gen. Frank M. Andrews was one of the founding fathers of the Air Force. Andrews' contribution to airpower rests on the unique role he played during his military career. He was responsible for orchestrating sweeping changes to the pre-World War II Army Air Corps, and he paved the way for the wartime Army Air Forces and postwar Air Force as a separate service.

By early 1943, Andrews was overall commander of U.S. forces in the European theater of operations, responsible for direction of the American strategic bombing campaign against Germany and planning the land invasion of occupied Western Europe. Andrews was killed in a B-24 Liberator crash along the Icelandic coast May 3, 1943. It was a loss of immense proportions, because Marshall ranked Andrews as one of the nation's "few great captains." Later, Marshall selected Dwight D. Eisenhower as Andrews' successor. In 1945, Hap Arnold, then leader of the Army Air Forces, renamed Camp Springs Army Airfield, Md., as "Andrews Field." Later, as Andrews AFB, it became the "gateway to the capital."

Throughout the years, some have speculated on what "might have been" had Andrews lived to see victory in Europe. But his place in history does not rest on that. His true significance lies in the crucial role he had in the evolution of the Army air arm into a separate service. The wartime numbered Air Forces, built on the GHQ Air Force foundation, were the basis of the early postwar Strategic Air Command, Tactical Air Command, and Air Defense Command. When a separate Air Force was established in 1947, the functions of GHQ Air Force were transferred to the chief of staff of the new U.S. Air Force. But that was not the end of the Frank Andrews story. After the Cold War, command and control doctrine for air combat forces came full circle in a revival of the prewar concept of a single combat air command. In June 1992, the Air Force established a new Air Combat Command, which, once again, centralized control nationwide of all domestic air combat units -- bombardment, attack, and fighter -- under a single air officer at Langley, reminiscent of Andrews' prototype combat command.

Directed from the same historic building Andrews used to lead GHQ Air Force, the new Air Combat Command had striking conceptual similarities to its forerunner from 1935. That historical parallel remains a reminder of the central role Andrews played as a founding father of the Air Force.

At a memorial service for Andrews in the chapel at Ft. Myer, Va., General George C. Marshall himself gave the eulogy. He reminded the mourners, "No Army produces more than a few great captains." He added, "General Andrews was undoubtedly one of these."

Andrews's dream of a separate Air Force needed four more years to come to fruition, but his contemporaries knew well the importance of the role he had played. In July 1947, President Harry Truman signed the National Security Act authorizing a separate Air Force within a unified National Military Establishment.

MORE ABOUT HER HUSBAND (from The National Aviation Hall of Fame):

Born in Nashville, Tennessee on February 3, 1884. Of English descent, Frank Andrews' father was James David Andrews, a newspaper publisher and real estate dealer, and his mother was Lulu Adaline (Maxwell) Andrews.

Andrews attended public grade school in Nashville, and then at age 13, he entered the Montgomery Bell Academy, from which he graduated in 1901. The following year he was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York on July 31, 1902. He graduated from the Academy on June 12, 1906 and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. cavalry. Andrews remained in the cavalry for eleven years, and he served at various posts, including the Philippines and Hawaii.

After being detailed to Ft. Ethan Allen in Vermont in December 1913, he met Jeanette Allen, the daughter of General Henry T. Allen. She not only liked horses and polo but she also played polo with Army teams. Even though General Allen is reported to have said that no daughter of his would ever marry an aviator, Andrews became interested in flying during their courtship. But he bided his time and won her hand. They were married on March 18, 1914 and three children were later born to them: Josephine, Allen and Jean.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Andrews thought his cavalry unit would not be sent overseas, so he transferred to the Aviation Section of the Army Signal Corps. After a short time in the office of the Aviation Section in Washington, DC, Andrews went to Rockwell Field, California, in 1918. There, he earned his aviator wings at the age of 34. Ironically, Andrews never went overseas during the war. Instead, he commanded various airfields around the United States and served in the war plans division of the Army General Staff in Washington, DC. Following the war, he replaced Brig. Gen. William "Billy Mitchell as the air officer assigned to the Army of Occupation in Germany

After first attending the Field Artillery School of Fire at Fort Sill in Oklahoma, he then reported for duty in the Air Division in the Office of the Chief Signal Officer in Washington, D.C. in September 1917. In working for the Chief Signal Officer, Andrews had an opportunity to observe America's first large-scale efforts to build up its airpower in accordance with the Aviation Act of 1917. Congress had appropriated $640 million in a belated effort to provide 5,000 warplanes, 4,500 trained pilots and 50,000 mechanics for the war effort by June, 1918. However, he found that while the Chief Signal Officer was responsible for training and organization, he had no control over procurement and operations. As a result of these divided command responsibilities, the aeronautical goals were never fully achieved. However, the lesson was not lost on Andrews, who became a temporary lieutenant on January 30, 1918.

In April 1918, Andrews became commander of Rockwell Field on North Island off San Diego. There he finally earned his wings as a Junior Military Aviator in July 1918 at the age of 34, which was considered old. Subsequently, he commanded Carlstrom Field and Dorr Field at Arcadia in Florida. Then in October 1918, he became Supervisor of the Southeastern Air Service District with headquarters in Montgomery, Alabama.

After World War I ended in November, 1918, Andrews returned to Washington, D.C. on March 21, 1919, where he became Chief of the Inspection Division and a member of the Advisory Board in the Office of the Director of the Air Service. Then on March 29, 1920, he was assigned to serve with the War Plans Division of the War Dept.'s general staff. During this tour, he reverted to his permanent rank of captain on April 3, 1920, but was then promoted to the permanent rank of major in the Regular Army on July 1, 1920.

On August 14, 1920, Andrews was sent to Germany to serve with the American Army of Occupation. There he first became Air Service Officer of the American Forces in Germany. Then in June 1922, he became Assistant to the Officer in Charge of Civil Affairs in the Headquarters of the American Forces at Coblentz, Germany.

After returning to the U.S. in February 1923, Andrews served in the Office of the Chief of the Air Service in Washington, D.C. and supervised the Training and War Plans Divisions. Then in June 1923, he became Executive Officer at Kelly Field at San Antonio, Texas. In July 1925, he became Assistant Commandant of Kelly, in command of the 10th School Group at the Air Service Advanced Flying School there. On June 30, 1926, he became Commandant of the School.

In September 1927, Andrews entered the Air Corps Tactical School at Langley Field in Virginia. Upon graduation in June 1928, he remained at Langley, where he served with the 2nd Wing Headquarters until July 16, 1928. He then attended the Command and General Staff School at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas. After graduation in June 1929, he was assigned to duty in the Office of the Chief of the Air Corps in Washington, D.C. There he was promoted to lieutenant colonel on January 13, 1930. Andrews served as the chief of the Army Air Corps' Training and Operations Division for a year before taking command of the 1st Pursuit Group at Selfridge Field, Michigan. He served in this office until August 15, 1932, when he entered the Army War College in Washington, D.C.

After graduation from the Army War College in 1933, Andrews returned to the General Staff in 1934.

On October 10, 1934, he returned to duty with the War Department general staff and served its Operations and Training Branch. This was a very important period in his career for he participated in the reorganization of the Army Air Corps and in the planning for the establishment of the Army General Headquarters Air Force.

This was a turning point for the Air Corps, for the GHQ Air Force within the Army was an operating air arm. He was named the Acting Commanding Officer of the GHQ Air Force until February 28, 1935. Then on March 1, 1935 he became its Commanding General when he was appointed to the temporary rank of Brigadier General, being selected over 12 senior colonels and lieutenant colonels. He established the headquarters of the new independent strategic striking force at Langley Field in Virginia.

As the first commander of the GHQ Air Force, Andrews was also the organizer of that command and he selected the most energetic of the airpower enthusiasts in uniform for his staff. They were dedicated and purposeful airmen who believed in developing the capabilities of large bombers and were willing to put up with the frustrations of their mission. The new organization was the first American approach to independent air operations. By the creation of this new organization, the Army Air Corps was taken away from the scattered control of nine Corps Area commanders and concentrated under one head, making it a highly centralized combat unit, as had been recommended by the famous Baker Board the year before.

Theoretically, Andrews command was a concentrated striking force of all types of military aircraft. Before, the tactical units of the Air Corps had been scattered all over the U.S. under many general officers and no plans existed for this mass employment. Andrews welded these dispersed squadrons into small but efficient fighting forces of three wings: the Atlantic Wing based at headquarters at Langley Field in Virginia; the Pacific Wing at Hamilton Field in California; and the Southern Wing at Fort Crockett in Texas. Later this Southern Wing was moved to Barksdale Field in Louisiana.

He trained this striking force to concentrate rapidly on various airfields along the vast perimeter of the continental U.S. At first, secret mass flights were conducted across the continent. In later maneuvers, bombardment aviation ranged far out to sea to intercept simulated enemy task forces. All of this brought questions from the press, but they found no sensationalism in Andrews' sober modesty. He said "We must realize that in common with the mobilization of the Air Force in this area, the ground arms of the Army would also be assembling, prepared to take a major role in repelling the enemy.---I want to ask that you do not accuse of trying to win a war alone."

On December 26, 1935, Andrews was promoted to the temporary rank of major general. For the next four years, he continuously studied how to improve the GHQ Air Force and how to make it a striking force that could be ordered to any point in the world for effective action.

By now he had become an ardent supporter of the big bomber. He also personally helped to demonstrate their utility on August 24, 1935, when he piloted a Martin B-12 seaplane with 1,202.3 and 2,204.6 pound payloads to new 1,000 kilometer closed-course records. He also had a zest for flight in rain, storm and fog and made hundreds of instrumental flights and landings to prove their practicality under such conditions.

On June 29, 1936 Andrews and Major John Whitely and their crew established an international airline distance record for amphibians by flying a Douglas YOA-5 amphibian powered by two Wright Cyclone 800 horsepower engines from San Juan, Puerto Rico to Langley Field, Virginia, a distance of 1,430 miles, which was officially recognized by the National Aeronautic Association and the Federation Aeronautique Internationale. When urged to give up flying after this he said "I don't want to be one of those generals who die in bed."

In April 1937, Andrews was rated as a command pilot and combat observer. By now he had become an ardent support of the new long-range, four-engine Boeing YB-17A Flying Fortress bomber, the first of which had been delivered to the 2nd Bombardment Group at Langley Field on March 1, 1937. On October 9, 1937, he pleaded for more and bigger bombers and said "Air attacks cannot be stopped by any means now known. The main reliance to defeat an enemy air force must be bombardment aviation directed against his bases and airplanes on the ground. The airpower of a nation is what is actually in the air today; that which is on the drawing board---cannot become its airpower until five years from now, --- too late for tomorrow's employment."

Andrews was always eager to take advantage of any war game to give tactical training to his bombardment units. These were exercises with aircraft bombing land targets and then targets towed by naval vessels. He used every other opportunity to demonstrate the capabilities of big bombers. One demonstration of the B-17's capabilities came on February 27, 1938 when six from the 2nd bombardment group, led by Colonel Robert Olds, made a 5,225 mile Goodwill Flight from Miami, Florida to Buenos Aires, Argentina with a stop en route to Lima, Peru. They then returned to Langley Field, Virginia.

The first leg of the trip was the longest Air Corps mass flight to date and took 33-1/2 hours. The return flight took 33-3/4 hours. Then in August, 1938, the first B-15 bomber, powered by four 1,000 horsepower engines was delivered to the 2nd Bombardment Group. Later, one made history by flying from Langley Field to Chile in 29 hours 53 minutes carrying 3,250 pounds of medical supplies aboard for earthquake victims.

With the clouds of war darkening over Europe, Andrews fought very hard for a stronger American Air Force, particularly one fully equipped with heavy bombers. On January 16, 1939, he told members of the National Aeronautic Association at their annual convention in St. Louis that the U.S. was a fifth or sixth rate air power. Though more tactful than his hero Billy Mitchell, he was also equally persistent and told a supposedly secret session of the House of Representatives "To ensure against air attacks being launched from any of these bases (in the Caribbean and in South America)---they must be kept under constant surveillance---and we must be ready to bomb such installations as they are discovered. If the situation is sufficiently vital to require it, we must be prepared to seize these outlying bases to prevent their development by the enemy as bases of operation against us."

This statement found its way into the press and Andrews was publicly censured by the President of the U.S. who said that these views were "not those of the White House or the nation." Five years later, such a statement would be viewed as one required by "Hemisphere Defense." However, his endorsement of such a policy did not please most of the members of the Army General Staff, who still believed that Army aviation should be nothing more than "the eyes of the artillery." Consequently, when his tour as commander of the GHQ Air Force ended in March 1939, he was reverted to his permanent rank of colonel and was ordered to Ft. Sam Houston, Texas as Air Officer of the Eighth Corps Area, --- the same post that his mentor, Colonel Billy Mitchell, had been exiled ten years before.

Fortunately, Andrews had important friends who believed in him, his abilities, and the scope of his knowledge and the breadth of his experiences. He had previously taken General George C. Marshall on a tour of aircraft plants and the three bases of the GHQ Air Force and had succeeded in winning him over as a new ally for the cause of airpower. Consequently, when General Marshall was appointed as Chief of Staff of the Army, he selected Andrews to serve the War Department General Staff in Washington, D.C. as Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations and Training (G-3). He also promoted him to the permanent rank of Brigadier General in the regular army on July 1, 1939. He thus became the first airman to handle the Regular Army's organization and training programs.

Marshall's choice was based on the knowledge that Andrews was not only a distinguished military aviator, but that he was also highly skilled in international relations. In addition, he was fully versed in the classic management of ground warfare, and the only American officer with experience in the command of a balanced and integrated air arm.

In Andrews he saw the emergence of a new kind of Army leader in American History, ---one with a knowledge of airpower at the command level and a depth of general staff experience,---qualities not then common among ground or air officers. In October 1940, he was promoted to the temporary rank of major general.

After the outbreak of World War II in Europe in September 1939, the importance of the Panama Canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and the entire Caribbean area and their adequate defense became a matter of great concern to the War Department. Among the measures taken to strengthen the defenses in this area was the appointment by President Roosevelt of Andrews as Commander of Panama Air Force on November 14, 1940.

On September 19, 1941, he was placed in charge of the Caribbean Defense Command and the Panama Canal Department and elevated to the rank of lieutenant general. As such, he was the first Army Air Corps officer to head a joint command and to hold a major Army Area command. There he was responsible for defending an area extending from his Canal Zone headquarters to Trinidad, and to Brazil and Ecuador.

One of his greatest tasks was to insure effective coordination of Navy, Army, Air Corps and Latin American forces. He organized the Air Force of the Caribbean Defense Command on a theater-wide basis and divided into bomber, interceptor and service commands. His chief activity became anti-submarine warfare from the air. He also commanded anti-aircraft defenses, land-based infantry units, and essential Army engineer units at score of jungle bases. The Caribbean Defense Command was unique in that it possessed airborne forces on December 7, 1941, the "Day of Infamy," when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entered World War II.

In 1942, he received the Distinguished Service Medal with the following citation: "For exceptionally meritorious services to the Government in positions of great responsibility as Commander of the Panama Canal Air Force from November 14, 1940 to September 19, 1941. His wide experience in the Army Air Forces enabled him to supervise and coordinate the numerous complicated factors involved in providing and maintaining air equipment and trained organizations available for combat operations. Through intimate knowledge and by inspirational leadership, sound judgment and devotion to duty, General Andrews created a strong tactical air command vital to the security of the Panama Canal. As Commanding General, Caribbean Defense Command, from Sept. 20, 1941, to November 9, 1942, he rendered services to the Government of outstanding character."

Andrews was also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in December 1942 with the following citation: "Frank M. Andrews, lieutenant general, U.S. Army. For extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flights in furtherance of the development and expansion program of the Army Air Forces. Since November 1940, as Senior Air Officer and Commanding General of the Caribbean Defense Command, a position of great responsibility, he participated in numerous aerial flights throughout the area of his command in order to supervise personally the establishment of air bases and other defense installation therein. General Andrews, by frequent flights both day and night over water in all kinds of weather, and using airplanes available even though not always best suited for the mission, demonstrated to the flying personnel of his command the practicability of an effective air patrol over the extensive are for which he was responsible. By precept and example in important, difficult and often hazardous flying duties, General Andrews established an effective air patrol which has proven its effectiveness in operations against the enemy. His willingness to lead the way created for the air command under his jurisdiction, a spirit of confidence, loyalty and enthusiasm.

Shortly after the Allies invaded North Africa under Operation TORCH, Andrews was picked by President Roosevelt, General Marshall and General Hap Arnold to become Commander of U.S. Forces in the Middle East. Five days later, he flew to Cairo, Egypt, where he established his command headquarters. There he gained experience in actual combat operations and in working with America's allies. Under his skillful command, the U.S. Ninth Air Force played a vital part in the Allied offensive, carrying out with conspicuous success the bombing of enemy-held ports and other targets, and destroying numerous fighter aircraft. As a result, the British Eighth Army was able to drive Axis Power forces under the command of German General Rommel back from El Alemein on the Egyptian border and send them on a disastrous retreat toward Tunis.

Andrews also represented his command at the conferences between President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill at Casablanca in January, 1943, where it was decided to establish a European Theater of Operations as a prelude to the later invasion of Europe. When the combined British and American heavy bomber offensive against Germany was approved at Casablanca, General Marshall selected Andrews as Commanding General of the U.S. forces in the European theater of operations with headquarters in London. In this capacity, Andrews' primary objective was to "increase and intensify the bombing of the enemy." His outstanding knowledge of every phase of airpower was an invaluable asset to the Allies in the early stages of planning and executing the combined British and American "round-the-clock" bombing offensive against Germany. His base in England was soon described as "one long runway for daylight bomber attacks on Germany." He also prodded the development of jettisonable fuel tanks to enable Allied fighters to penetrate deeper into Germany while escorting the heavy bombers.

In March 1943, Andrews and Major General Ira C. Eaker, commander of the Eighth Air Force in Britain, received the personal congratulations of Prime Minister Churchill after a successful American bombing raid on the German submarine yards at Vegesack.

Andrews, one of the most promising Army Air Force leaders, was killed in an airplane accident in Iceland on May 3, 1943, while on an inspection trip there from England. His plane crashed into a lonely point of land in a very dense fog while trying to find its way to Reykjavik, killing all 14 persons aboard. Of Andrews' untimely death, Army Chief of Staff General Marshall said "...the loss to the nation of an outstanding soldier." He also called Andrews "a great leader" and added that "no army produces more than a few great captains. General Andrews was undoubtedly one of these and we mourn his death."

Only the tail gunner, S/Sgt. George A. Eisel of Columbus, Ohio, survived. Others killed in the crash included Adna Wright Leonard, presiding Methodist bishop of North America, who was on a pastoral tour; Chaplains Col. Frank L. Miller (Washington, D.C.) and Maj. Robert H. Humphrey (Lynchburg, Va.), accompanying Bishop Leonard; Brig. Gen. Charles M. Barth (hometown Walter, Minn.), Andrews' chief of staff; Col. Morrow Krum (Lake Forest, Ill.), press officer for the ETO; Lt. Col. Fred A. Chapman (Grove Hill, Ala.) and Maj. Theodore C. Totman (Jamestown, N.Y.), senior aides to Andrews; pilot Capt. Robert H. Shannon (Washington, Iowa), of the 330th Bombardment Squadron, 93rd Bomb Group; Capt. Joseph T. Johnson (Los Angeles); navigator Capt. James E. Gott (Berea, Ky.); Master Sgt. George C. Weir (McRae, Ark.); Tech. Sgt. Kenneth A. Jeffers (Oriskany Falls, N.Y.); and Staff Sgt. Paul H. McQueen (Endwell, N.Y.).

General Andrews was awarded an Oak Leaf cluster for his Distinguished Service Medal, posthumously, in July 1943, with the following citation: "For exceptionally meritorious service to the Government in a position of great responsibility. As Commanding General of the European Theater of Operations, General Andrews successfully met and solved many complex problems. His calm judgment, courage, resourcefulness and superior leadership have been an inspiration to the Armed Forces and of great value to his country."

Only 59 at the time of his death, Andrews was rated as a command pilot and had acquired 5,800 hours of flying, only 173 of which were flown as an observer. His other decorations included Commander of the Crown of Italy, Cruz Peruna de Aviacion of Peru, Order of the Sun of Peru, Army Occupation of Germany Medal, Order of Boyaca of Columbia (Grand Officer), Presidential Medal of Merit of Nicaragua, Order of Vasco Nunez de Balboa of Panama, El Sol del Peru (Grand Officer), and the Emblem of the Ejercito Argentino.

Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland, nine miles outside of Washington, D.C. was named in General Andrews' honor on March 31, 1949. It stands as a living memorial to one of the greatest pioneers of the modern U.S. Air Force. Then on April 2, 1954, the Andrews Engineering Building was dedicated in his honor at the Air Force Armament Center at Elgin Air Force Base in Florida.

PHOTO DESCRIPTIONS

Newly appointed as a temporary brigadier general, Frank M. Andrews stands in front of a Martin B-12 bomber at Langley Field, Va., in March 1935.

2. Paving the way: Remembering Frank Andrews by Dr. Henry O. Malone Former Army Historian 02/28/02 - HAMPTON, Va. (AFPN) -- For decades, Andrews Air Force Base, Md., has been the "gateway to the capital" for presidents and foreign leaders. Today, it is far more famous than the person for whom it was named. Most are unaware that Lt. Gen. Frank M. Andrews was one of the founding fathers of the Air Force. Andrews' contribution to airpower rests on the unique role he played during his military career. He was responsible for orchestrating sweeping changes to the pre-World War II Army Air Corps, and he paved the way for the wartime Army Air Forces and postwar Air Force as a separate service. March 1, 1935, marked a major milestone in the strategic development of American airpower, when Andrews, newly appointed as a temporary general officer, established a combat air command called General Headquarters Air Force at Langley Field, Va. This prototype major air command centralized for the first time control of all nine Army Air Corps combat groups -- bombardment, attack, and pursuit -- under a single air officer. That move was the first major step in the long process through which the Army air arm was transformed into a separate military service throughout the ensuing 12 years.

Earlier, as a lieutenant colonel commanding the historic 1st Pursuit Group at Selfridge Field, Mich., Andrews had been detached from group command in the fall of 1934 for special duty in the War Department general staff. His task was to develop a plan to solve the problem of fragmented command of the Army's air combat units with nine separate Army Corps area commanders. The result was creation of GHQ Air Force, composed of three large composite wings, on eight installations, coast to coast. One of his wing commanders was Brig. Gen. Henry H. "Hap" Arnold. During four volatile prewar years at the helm of GHQ Air Force, Andrews initiated sweeping and fundamental changes to the Army air arm, creating the conceptual and material foundations for a modern air combat force, often against formidable opposition. When he brought the first B-17 Flying Fortress into operational service in March 1937 at Langley Field, GHQ Air Force became the peacetime test bed for defining the role American airpower would play in World War II. It was the vanguard of the wartime Army Air Forces.

In 1939, on the eve of war in Europe, Andrews went to Washington as the first airman to head a War Department general staff division. He served as Army G-3 (Operations) under Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall. Vital decisions, resulting in virtual autonomy for the later Army Air Forces, owed much to the close professional relationship between Marshall and Andrews, going back to the GHQ Air Force era.

In 1940, Andrews went to Panama to build the air defenses of the Panama Canal. Promoted to lieutenant general in November 1941, Andrews became theater commander in the Caribbean, the first airman to head a joint warfighting command. In 1942, he became theater commander of U.S. forces in the Middle East, where he established 9th Air Force, the first U.S. tactical air force to see combat. By early 1943, Andrews was overall commander of U.S. forces in the European theater of operations, responsible for direction of the American strategic bombing campaign against Germany and planning the land invasion of occupied Western Europe.

Andrews was killed in a B-24 Liberator crash along the Icelandic coast May 3, 1943. It was a loss of immense proportions, because Marshall ranked Andrews as one of the nation's "few great captains." Later, Marshall selected Dwight D. Eisenhower as Andrews' successor. In 1945, Arnold, then leader of the Army Air Forces, renamed Camp Springs Army Airfield, Md., as "Andrews Field." Later, as Andrews AFB, it became the "gateway to the capital." Throughout the years, some have speculated on what "might have been" had Andrews lived to see victory in Europe. But his place in history does not rest on that. His true significance lies in the crucial role he had in the evolution of the Army air arm into a separate service.

The wartime numbered Air Forces, built on the GHQ Air Force foundation, were the basis of the early postwar Strategic Air Command, Tactical Air Command, and Air Defense Command. When a separate Air Force was established in 1947, the functions of GHQ Air Force were transferred to the chief of staff of the new U.S. Air Force. But that was not the end of the Frank Andrews story. After the Cold War, command and control doctrine for air combat forces came full circle in a revival of the prewar concept of a single combat air command. In June 1992, the Air Force established a new Air Combat Command, which, once again, centralized control nationwide of all domestic air combat units -- bombardment, attack, and fighter -- under a single air officer at Langley, reminiscent of Andrews' prototype combat command. Directed from the same historic building Andrews used to lead GHQ Air Force, the new Air Combat Command had striking conceptual similarities to its forerunner from 1935. That historical parallel remains a reminder of the central role Andrews played as a founding father of the Air Force.

Editor's Note: The author was chief historian for U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command until retiring in 1994. He was an aviation cadet in U.S. Air Force pilot class 55-N. Upon graduation he flew the F-86 Sabre with the 50th Fighter Bomber Wing for U.S Air Forces in Europe.

MORE DETAILED AND ADDITIONAL INFORMATION:

In February 1943, Lieutenant General Andrews became the commander of all United States forces in the European Theater of Operations. In his memoirs, Gen Henry H. "Hap" Arnold, commander of the Army Air Forces in World War II, expressed the belief that Andrews would have been given the command of the Allied invasion of Europe-the position that eventually went to Gen Dwight D. Eisenhower. However, on May 3, 1943, the B-24 carrying Andrews on an inspection tour crashed while attempting to land at the Royal Air Force Base at Kaldadarnes, Iceland. Andrews and thirteen others died in the crash, and only the tail gunner survived.

At approximately 3:30 p.m. Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) on May 3, 1943, B-24D (41-23728) crashed at position 22° 19' 30" west - 63° 54' north in Iceland and was destroyed. The pilot of the aircraft, Captain Robert H. Shannon, the copilot Lt. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, four additional crewmen and eight passengers were fatally injured. One crewman, the tail gunner, escaped with only minor injuries.

The B-24 was assigned to the 8th Air Force at Bovington, England. The mission was a scheduled cross-country flight from the United Kingdom to Meeks Field, Iceland to pass over Prestwick, Scotland. The aircraft approached Iceland from the southeast and contact was made with the land seven miles east of Alvidruhamrar lighthouse at 1:49 p.m. GMT. The aircraft proceeded west along the coastline at an altitude of about 200 feet, remaining under the clouds. At 2:38 p.m. GMT, the aircraft circled the Royal Air Force airdrome at Kaldadarnes five times at about 500 feet altitude. The airdrome control signaled the aircraft to land by using a green Aldas lamp as radio contact could not be established. The B-24 flew low over the runway, but the pilot did not attempt a landing. Instead, the aircraft proceeded westward along the coastline at an altitude of 60 feet.

At Reykjanes, the aircraft turned north and followed the coast for about 10 miles, to a point directly west of Meeks Field. The time was now 2:53 hours GMT. the plot by the Air Weather Service (AWS) faded at this point. No radio contact was made at any time with the aircrew, but the track was plotted by the AWS. The aircraft turned eastward and the pilot attempted to sight Meeks Field, but low visibility and rain prevented this. The survivor stated that the pilot indicated he was going to return to Kaldadarnes airdrome to land. Captain Shannon then attempted to follow the coastline by doing steep turns in an easterly direction.

The weather was closing down with low clouds, rain and reduced visibility. As he did not have any air-to-ground communications, the pilot attempted to maintain visual contact with the land by flying under the clouds. At 22° 19' 30" west - 63° 54' north, the aircraft flew into an 1100 foot hill, 150 feet from the top, while on a northeast course at a speed of at least 160 mph. The B-24's starboard wing dug into the 45° northwest slope of the hill. Upon impact, the aircraft disintegrated except for the tail gunner's turret which remained relatively intact.

There were statements in the report given by the weather officer at Kaldadarnes. They indicated that the weather was extremely low visibility, with a possible ceiling and visibility of zero at the point of impact. A wind of about 25 mph was blowing saturated air against the mountain and this would tend to form a cloud covering below that of the general ceiling level. The weather officer further stated that while weather observations were not taken from Kaldadarnes, he thought that continuous rain prevailed there with the clouds covering the hills in the accident vicinity during that period.

(a) Along with Arnold, he prepared the way for the rise of airpower in World War II.

II. The Influence of Frank Andrews

(i) By H.O. Malone

In early 1943, Lt. Gen. Frank M. Andrews was killed in the crash of his B-24 Liberator just as he stood on the threshold of playing a key role in the Allied victory in Europe. Andrews, at the time of his death, was commander of United States forces in the European Theater of Operations and as such was in charge of the overall direction of the US strategic bombing campaign as well as planning for the invasion of the Continent.

The death of Andrews was a major blow. Even before the war ended Gen. Henry H. "Hap" Arnold, Commanding General of the Army Air Forces, renamed the Army Air Field at Camp Springs, Md., for the fallen airman. For decades Andrews Air Force Base has been the "gateway to the capital" for Presidents and foreign leaders, and today it is far more famous than the person for whom it was named. Most are unaware that Andrews was one of the founding fathers of the Air Force.

The significance of his career does not revolve around the circumstances of his death or what "might have been" had he lived longer. It rests instead on the unique role he actually played during his military service. He was responsible for orchestrating sweeping changes to the prewar Army Air Corps. He prepared the way for the wartime Army Air Forces and postwar US Air Force.

Andrews was commissioned in 1906 at West Point and served in the cavalry until 1917. He transferred to aviation as a major during World War I and earned his pilot's wings in 1918. Later, he served in Air Service staff and command billets at home and overseas, as well as on the War Department General Staff. In 1928, he finished the Air Corps Tactical School at Langley Field, Va., and, unlike most airmen, graduated from both the Army Command and General Staff School and the Army War College.

The court-martial in December 1925 and resignation in February 1926 of Army Brig. Gen. William L. "Billy" Mitchell was a turning point for the Army air arm. In the wake of that episode, experienced Army airmen such as Majors Andrews and Arnold concluded that the overall goal of building a separate Air Force-Mitchell's goal and theirs-could be achieved only by means of an evolutionary process from within the War Department.

They believed two intermediate steps lay between the status quo Air Corps of the interwar years and an independent Air Force of the future. First, they recognized that the air arm would have to consolidate all domestic Army air combat forces under the central command of a single air officer. Second, the air arm would have to gain a large measure of autonomy in the War Department and use it to demonstrate the capabilities of airpower.

In both cases, Andrews was to play a leading role.

GHQ Air Force

Following World War I, centralized command of Army air combat units was the subject of a major debate. The Chief of the Air Service was neither a commander of combat forces nor a member of the War Department General Staff. Like the Chief of Infantry, he headed an Army combat arm but possessed no actual command authority over combat units in the field. Higher command over air combat units was fragmented among the nine Army corps area commanders, none of whom were air officers.

In the interwar period, a series of outside blue-ribbon advisory panels studied this issue for the Secretary of War. The work culminated in 1934 when the Baker Board recommended the consolidation of the Air Corps combat units under a single air officer. That "air force" commander would operate in wartime directly under the commander of Army field forces, working from a command post called General Headquarters, or GHQ, that would be created during wartime. The proposed combat air command would be the GHQ Air Force.

To prevent the de facto development of an autonomous air component within the War Department, the General Staff insisted that the proposed GHQ Air Force commander be independent of the Office of the Chief of the Air Corps. Thus, Maj. Gen. Benjamin D. Foulois, an airman who was the Chief of the Air Corps, would not gain command of GHQ Air Force but would continue to have oversight of noncombatant Air Corps functions, such as individual training, equipment development, and personnel management.

The Army Chief of Staff, Gen. Douglas A. MacArthur, approved this concept with its implied acknowledgment that the "air force" had a legitimate interest in conducting independent operations quite apart from support for land forces.

However, everyone recognized that these air combat units could not be created overnight, after wartime mobilization began, and so they would have to be in place in peacetime--prior to activation of the Army's wartime GHQ. The critical question was this: What would happen to command arrangements in times of peace when no GHQ even existed? The solution was that the designated commander of GHQ Air Force would report to the Army Chief of Staff, just like Foulois, the Chief of the Air Corps.

Thus the Army's air arm would be subdivided into a combat component (GHQ Air Force) and a support component (the Office of the Chief of the Air Corps), each independent of the other. Few believed that the division of command would yield the most effective employment of air assets. Still, centralized command under a single air officer of all air combat forces was itself a major step forward, allowing for rapid concentration of air combat units against a threat.

In the mid-1930s, the Army air combat contingent comprised only 32 squadrons, parceled out to nine combat groups. One of the groups was the historic 1st Pursuit Group at Selfridge Field, Mich., which was commanded by Andrews, who was well-prepared for the task of shaping up an effective air combat arm.

In late 1934, the Army cut short Andrews's command tour at the 1st Pursuit Group and detailed him back to the General Staff to work on the GHQ Air Force project. Not long after his return to Washington, MacArthur selected Andrews to organize and command GHQ Air Force at Langley Field.

MacArthur activated GHQ Air Force on March 1, 1935, with Andrews as commander, a move that brought Andrews a double promotion to the temporary grade of brigadier general. Col. Hugh J. Knerr was his chief of staff and Lt. Col. George C. Kenney his G-3 (operations staff officer). As consolidated under GHQ Air Force, each of the nine combat groups-based at eight different locations coast to coast-was assigned to one of three composite wings. These bombardment, attack, and pursuit groups represented GHQ Air Force's strategic, tactical, and air defense missions.

Arnold, newly promoted to brigadier, led the 1st Wing at March Field, Calif., with one attack and two bombardment groups. On the Atlantic coast, the 2nd Wing, with two bombardment and two pursuit groups, was the largest of the three subordinate commands, consisting of 15 flying squadrons and headquarters at Langley Field. In the south, the 3rd Wing, smallest of the three, operated from Barksdale Field, La. It had one pursuit and one attack group.

By December 1935 Army leadership had turned over, with MacArthur succeeded by Gen. Malin Craig. Andrews--who answered to Craig--was promoted to temporary major general. Foulois retired in that same month and his assistant, Oscar Westover, a former balloonist, became Chief of the Air Corps. Hap Arnold, who begged to stay at March Field with the flying units, was sent to Washington to become Westover's assistant.

Amid all of the bureaucratic shuffling, Andrews faced a major problem: He had no truly effective long-range, heavy bombers to carry out the kinds of independent air missions fundamental to the GHQ Air Force concept. Solving that problem was one of his most pressing tasks, and it was only because of the persistence and tenacity of Andrews and his chief of staff, Knerr, that Boeing's new, four-engine B-17 bomber reached full deployment status. It was a fight that nearly ended his career.

The first B-17 Flying Fortresses were assigned in 1937 to the 2nd Bomb Group at Langley, led by Lt. Col. Robert Olds. The 2nd BG served, in effect, as the operational test bed for this important weapons system. One of Olds's operations officers, 1st Lt. Curtis E. LeMay, was not only a pilot but also an expert navigator and bombardier.

Bomber Demonstrations

Andrews was fond of demonstrating the capabilities of the big bomber. For instance, in February 1938, six B-17s from the 2nd BG under Olds's command made a 5,225-mile Goodwill Flight that included stops from Miami to Buenos Aires and the return to Langley. Later, on May 12, 1938, during Army-Navy war games, Andrews proved that a B-17 could intercept an "enemy aircraft carrier" (the role was played by an Italian ocean liner) when three of the big bombers located the ship more than 700 miles offshore in the Atlantic. The lead navigator was LeMay.

By the summer of 1938, however, the B-17 was in trouble, with the War Department threatening to shut down production in a cost-cutting effort. Senior Army officers believed that larger numbers of short- and medium-range, twin-engine bombers could do a better job than smaller numbers of large, expensive, long-range bombers with four engines.

Andrews, still a temporary major general, invited Brig. Gen. George C. Marshall, new chief of war plans on the General Staff, for an all-day briefing at his Langley Field headquarters. Marshall accepted and was favorably impressed.

Shortly afterward, Marshall accompanied Andrews on an extended inspection trip to GHQ Air Force combat units across the country, as well as visits to Air Corps support installations and several aircraft manufacturing plants. A crucial stop came at the Boeing plant in Seattle, where Marshall was allowed to see firsthand the B-17 production line. Marshall became convinced that the aircraft was not only useful but critical to US defenses. Marshall's opinion eventually went a long way toward saving the controversial aircraft, which Army officers derided as "Andrews's Folly."

Moreover, Marshall's trip with Andrews marked the beginning of a professional relationship between the two that would be of great importance to the future of the Army air arm.

Andrews spent four crucial years as head of GHQ Air Force. His actions did not sit well with Craig, the Chief of Staff of the Army. On March 1, 1939, Andrews completed his command tour at GHQ Air Force, but Craig declined to offer Andrews a new assignment in a general officer's post. He thus was forced to revert to his permanent grade of colonel and was sent to San Antonio, as VIII Corps air officer, finding himself in exactly the same job as that to which Billy Mitchell had been relegated in 1925. Craig's decision, however, could not change the fact that the consolidation of air combat units under Andrews in GHQ Air Force represented an important milestone in the strategic development of American airpower.

FDR's Surprise

Unlike Mitchell, however, Andrews did not see his career collapse in Texas. Four months after his exile, on July 1, 1939, Craig went on terminal leave prior to his planned Sept. 1 retirement. Craig could not have known that President Franklin D. Roosevelt would pass over scores of more senior generals to reach down and select Marshall to become the new Army Chief of Staff, but that is what happened.

Marshall took charge immediately as acting Chief of Staff. One of his first actions-taken despite fierce objections from Craig-was to recall Andrews to Washington in August as the assistant chief of staff for operations and training, the G-3 of the entire Army. Andrews also was promoted to the permanent grade of brigadier general.

In this remarkable turn of events, Andrews, who had for so long had to fight the War Department General Staff in trying to build an effective air combat force, held a position of first among equals on the General Staff. It was a historic appointment; he was the first airman to head a General Staff division. It was especially important in light of the fact that, in just over a month, war erupted in Europe.

In that key post within, Andrews was able to formulate Army-wide policy on important issues of concern to the air arm, such as doctrine for close air support of ground forces. And, for the first time, air officers were assigned in significant numbers to the War Department General Staff. Andrews was also able to advise Marshall on a whole range of issues regarding further development of the nation's airpower, as it became increasingly evident that the United States would not be able to avoid involvement in the war.

Building an effective air force also required a large measure of autonomy for airmen. Andrews never had it during his time as the commander of GHQ Air Force, but during his Langley years and later in Washington, he played a key role in laying the foundation for virtual autonomy.

Now it was time for him to leave Washington. Issues of Western hemisphere defense came to the forefront in fall 1940, and Marshall decided to reassign Andrews to the Canal Zone to organize air defenses of the Panama Canal. His Panama Canal Air Force became the prototype for all subsequent overseas air forces.

With the departure of Andrews from the General Staff, Marshall took another bold step, this one involving Hap Arnold, who had become Air Corps Chief, succeeding Westover when the latter died in a crash in 1938. Marshall gave Arnold the additional title of acting deputy chief of staff for air. That appointment enhanced Arnold's standing considerably within the War Department and enabled him to fill the gap on Marshall's staff created by Andrews's reassignment.

Now, Army Air Forces

Six months later, in March 1941, the GHQ Air Force flag at Langley was shifted to Bolling Field, D.C. Marshall soon approved the concept of an umbrella organization to coordinate operations of both GHQ Air Force and the Office of the Chief of the Air Corps, to be called Army Air Forces.

On June 20, 1941, Arnold was reassigned as Chief, Army Air Forces. Simultaneously, GHQ Air Force became Air Force Combat Command.

Late in 1941, on the eve of America's entry into World War II, Marshall took two steps to enhance further the standing of the air arm within the War Department. First, he advanced Andrews to lieutenant general and reassigned him as commander of Caribbean Defense Command, making him the first airman to head a unified theater command overseas. Andrews's pioneering work as a joint forces commander established valuable precedents both for directing theater commands overseas in wartime and for integrating air forces in such commands.

Second, Marshall approved a plan to reorganize the War Department so as to give the Army Air Forces parity with ground components. However, the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor delayed implementation a few months. The restructuring finally went into effect March 9, 1942, introducing fundamental changes of great significance to the air arm.

Both the Office of the Chief of the Air Corps and Air Force Combat Command (GHQ Air Force) were abolished. Their functions were merged into the Army Air Forces, whose Chief, Arnold, became Commanding General. Furthermore, a new Air Staff, separate from the War Department General Staff, was created for the Army Air Forces, which emerged with a standing in the Department equal to the new Army Ground Forces and Army Services of Supply.

Arnold's post as deputy chief of staff of the Army for air put the Army Air Forces on a level different from the other two components in the War Department. Consequently, Marshall arranged for the AAF to have a seat at both the Anglo-American Combined Chiefs of Staff and US Joint Chiefs of Staff. Thus, the AAF finally achieved the virtual autonomy that GHQ Air Force needed but never had. This was the second major step on the road toward a separate Air Force. It rested on the perceptive understanding Marshall had of airpower, fostered by his close association with Andrews.

Late in 1942, Marshall moved Andrews from Caribbean Defense Command to leadership of US forces in the Middle East. Andrews was in that post for only a short time but he established Ninth Air Force within his Middle East command, the first "tactical" air force to drop bombs in Europe.

Early in 1943, at the Casablanca Conference, Marshall nominated Andrews as commander of the US European Theater of Operations, to direct the American aerial bombing campaign against Germany and plan for the eventual land invasion of the European continent. It was Andrews's third joint theater command.

On the other side of the world, Andrews's former G-3 at Langley, George Kenney, was leading the air war for MacArthur in the Southwest Pacific Theater. Elsewhere, other veterans of the GHQ Air Force era occupied important positions in the command structure, at home and overseas. GHQ Air Force had indeed, as Arnold recognized, been the forerunner of the Army Air Forces, laying the foundation for its success in wartime. During World War II he wrote, "Today, when American bombers fly a successful mission in any theater of war, their achievement goes back to the blueprints of the General Headquarters Air Force. Our operations were based on the needs and problems of our own hemisphere, with its vast seas, huge land areas, great distances, and varying terrains and climates. If we could fly here, we could fly anywhere, and such has proved to be the case."

For Andrews, promotion to full general was on the horizon. The end, however, came abruptly on May 3, 1943, when he died on a rugged mountaintop in Iceland. An editorial in the New York Times compared Andrews to Billy Mitchell, noting that "not even General Mitchell plugged harder for the Army air arm."

At a memorial service for Andrews in the chapel at Ft. Myer, Va., Marshall himself gave the eulogy. He reminded the mourners, "No Army produces more than a few great captains." He added, "General Andrews was undoubtedly one of these."

Andrews's dream of a separate Air Force needed four more years to come to fruition, but his contemporaries knew well the importance of the role he had played. In July 1947, President Harry Truman signed the National Security Act authorizing a separate Air Force within a unified National Military Establishment. That bill transferred the dormant statutory functions of the Commanding General of GHQ Air Force to the Chief of Staff of the new US Air Force. Forty-five years later, in June 1992, domestic air combat units--bombardment, attack, and fighter--were once again consolidated under a single air officer at Langley comparable to what had happened there in 1935.

Air Combat Command, directed from the same historic building from which Andrews led GHQ Air Force, shares a striking conceptual similarity to Andrews's major air command. That parallel can serve as a reminder of the unique role Andrews played in shaping the course of events that transformed the Army air arm into the United States Air Force.

H.O. Malone was an aviation cadet and flew F-86 Sabres in Europe. He taught European history at Texas Christian University and spent 21 years in the Department of Defense, retiring in 1994 as chief historian, Army Training and Doctrine Command. This is his first article for Air Force Magazine.

After marrying Jeannette "Johnny" Allen, the high-spirited daughter of Major General Henry Tureman Allen, in 1914, her husband gained entrée into elite inner circles of Washington society and within the military. They were the parents of three children: Josephine (1914-1977), Allen (1917-2008), and Jean (b. 1923).

Like many other cavalrymen, her future husband, Frank Maxwell Andrews, became an ardent and hard-riding polo player. After being detailed to Ft. Ethan Allen in Vermont in December 1913, he met Jeanette Allen, the daughter of General Henry T. Allen. She not only liked horses and polo but she also played polo with Army teams. Even though General Allen is reported to have said that no daughter of his would ever marry an aviator, Andrews became interested in flying during their courtship. But he bided his time and won her hand. They were married on March 18, 1914 and three children were later born to them: Josephine, Allen and Jean.

A story related in the press many times during Andrews' lifetime claimed that General Allen forestalled the aeronautical aspirations of his future son-in-law by declaring, as stated above, that no daughter of his would marry a flyer. Andrews' service records, however, show that his commanding officer in the Second Cavalry vetoed his application for temporary aeronautical duty with the Army Signal Corps in February 1914, a decision that held firm despite a plea from the Chief Signal Officer's for reconsideration by higher-ups.

Jeannette's husband was commander of all Forces in Europe during the early stages of World War II, serving with General Dwight D. Eisenhower at times, and when Eisenhower was appointed to command all allied forces in Europe, Andrews succeeded him as commander of US forces. Two months later in May 3, 1943, he was killed in the crash of a B-24 in Iceland.* Before his premature death in 1943, Frank Maxwell Andrews played a major role in building the small US Army Air Corps of the 1930s into the powerful US Army Air Forces of World War II. Furthermore, he had become one of the key military commanders in the United States' armed forces.

[* Only the tail gunner, S/Sgt. George A. Eisel of Columbus, Ohio, survived.]

U.S. Veterans Gravesites, ca. 1775-2006

Name: Jeannette Allen Andrews

Service Info.: AR United States Army

Birth Date: 28 Apr 1889

Death Date: 19 Sep 1962

Relation: Wife of Veteran

Interment Date: 20 Sep 1962

Cemetery: Arlington National Cemetery

Cemetery Address: C/O Director Arlington, VA 22211

Buried At: Section 2 Site 1883-A

Her husband was an outspoken proponent of air power and Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland is named in his honor. Jeanette Allen Andrews, the wife of Frank Maxwell Andrews is buried with her husband in Section 3 of Arlington National Cemetery.

Remembering Frank Andrews

by Dr. Henry O. Malone

Former Army Historian 02/28/02 - HAMPTON, Va. (AFPN)

- For decades, Andrews Air Force Base, Md., has been the "gateway to the capital" for presidents and foreign leaders. Today, it is far more famous than the person for whom it was named. Most are unaware that Lt. Gen. Frank M. Andrews was one of the founding fathers of the Air Force. Andrews' contribution to airpower rests on the unique role he played during his military career. He was responsible for orchestrating sweeping changes to the pre-World War II Army Air Corps, and he paved the way for the wartime Army Air Forces and postwar Air Force as a separate service.

By early 1943, Andrews was overall commander of U.S. forces in the European theater of operations, responsible for direction of the American strategic bombing campaign against Germany and planning the land invasion of occupied Western Europe. Andrews was killed in a B-24 Liberator crash along the Icelandic coast May 3, 1943. It was a loss of immense proportions, because Marshall ranked Andrews as one of the nation's "few great captains." Later, Marshall selected Dwight D. Eisenhower as Andrews' successor. In 1945, Hap Arnold, then leader of the Army Air Forces, renamed Camp Springs Army Airfield, Md., as "Andrews Field." Later, as Andrews AFB, it became the "gateway to the capital."

Throughout the years, some have speculated on what "might have been" had Andrews lived to see victory in Europe. But his place in history does not rest on that. His true significance lies in the crucial role he had in the evolution of the Army air arm into a separate service. The wartime numbered Air Forces, built on the GHQ Air Force foundation, were the basis of the early postwar Strategic Air Command, Tactical Air Command, and Air Defense Command. When a separate Air Force was established in 1947, the functions of GHQ Air Force were transferred to the chief of staff of the new U.S. Air Force. But that was not the end of the Frank Andrews story. After the Cold War, command and control doctrine for air combat forces came full circle in a revival of the prewar concept of a single combat air command. In June 1992, the Air Force established a new Air Combat Command, which, once again, centralized control nationwide of all domestic air combat units -- bombardment, attack, and fighter -- under a single air officer at Langley, reminiscent of Andrews' prototype combat command.

Directed from the same historic building Andrews used to lead GHQ Air Force, the new Air Combat Command had striking conceptual similarities to its forerunner from 1935. That historical parallel remains a reminder of the central role Andrews played as a founding father of the Air Force.

At a memorial service for Andrews in the chapel at Ft. Myer, Va., General George C. Marshall himself gave the eulogy. He reminded the mourners, "No Army produces more than a few great captains." He added, "General Andrews was undoubtedly one of these."

Andrews's dream of a separate Air Force needed four more years to come to fruition, but his contemporaries knew well the importance of the role he had played. In July 1947, President Harry Truman signed the National Security Act authorizing a separate Air Force within a unified National Military Establishment.

MORE ABOUT HER HUSBAND (from The National Aviation Hall of Fame):

Born in Nashville, Tennessee on February 3, 1884. Of English descent, Frank Andrews' father was James David Andrews, a newspaper publisher and real estate dealer, and his mother was Lulu Adaline (Maxwell) Andrews.

Andrews attended public grade school in Nashville, and then at age 13, he entered the Montgomery Bell Academy, from which he graduated in 1901. The following year he was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York on July 31, 1902. He graduated from the Academy on June 12, 1906 and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. cavalry. Andrews remained in the cavalry for eleven years, and he served at various posts, including the Philippines and Hawaii.

After being detailed to Ft. Ethan Allen in Vermont in December 1913, he met Jeanette Allen, the daughter of General Henry T. Allen. She not only liked horses and polo but she also played polo with Army teams. Even though General Allen is reported to have said that no daughter of his would ever marry an aviator, Andrews became interested in flying during their courtship. But he bided his time and won her hand. They were married on March 18, 1914 and three children were later born to them: Josephine, Allen and Jean.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Andrews thought his cavalry unit would not be sent overseas, so he transferred to the Aviation Section of the Army Signal Corps. After a short time in the office of the Aviation Section in Washington, DC, Andrews went to Rockwell Field, California, in 1918. There, he earned his aviator wings at the age of 34. Ironically, Andrews never went overseas during the war. Instead, he commanded various airfields around the United States and served in the war plans division of the Army General Staff in Washington, DC. Following the war, he replaced Brig. Gen. William "Billy Mitchell as the air officer assigned to the Army of Occupation in Germany

After first attending the Field Artillery School of Fire at Fort Sill in Oklahoma, he then reported for duty in the Air Division in the Office of the Chief Signal Officer in Washington, D.C. in September 1917. In working for the Chief Signal Officer, Andrews had an opportunity to observe America's first large-scale efforts to build up its airpower in accordance with the Aviation Act of 1917. Congress had appropriated $640 million in a belated effort to provide 5,000 warplanes, 4,500 trained pilots and 50,000 mechanics for the war effort by June, 1918. However, he found that while the Chief Signal Officer was responsible for training and organization, he had no control over procurement and operations. As a result of these divided command responsibilities, the aeronautical goals were never fully achieved. However, the lesson was not lost on Andrews, who became a temporary lieutenant on January 30, 1918.

In April 1918, Andrews became commander of Rockwell Field on North Island off San Diego. There he finally earned his wings as a Junior Military Aviator in July 1918 at the age of 34, which was considered old. Subsequently, he commanded Carlstrom Field and Dorr Field at Arcadia in Florida. Then in October 1918, he became Supervisor of the Southeastern Air Service District with headquarters in Montgomery, Alabama.

After World War I ended in November, 1918, Andrews returned to Washington, D.C. on March 21, 1919, where he became Chief of the Inspection Division and a member of the Advisory Board in the Office of the Director of the Air Service. Then on March 29, 1920, he was assigned to serve with the War Plans Division of the War Dept.'s general staff. During this tour, he reverted to his permanent rank of captain on April 3, 1920, but was then promoted to the permanent rank of major in the Regular Army on July 1, 1920.

On August 14, 1920, Andrews was sent to Germany to serve with the American Army of Occupation. There he first became Air Service Officer of the American Forces in Germany. Then in June 1922, he became Assistant to the Officer in Charge of Civil Affairs in the Headquarters of the American Forces at Coblentz, Germany.

After returning to the U.S. in February 1923, Andrews served in the Office of the Chief of the Air Service in Washington, D.C. and supervised the Training and War Plans Divisions. Then in June 1923, he became Executive Officer at Kelly Field at San Antonio, Texas. In July 1925, he became Assistant Commandant of Kelly, in command of the 10th School Group at the Air Service Advanced Flying School there. On June 30, 1926, he became Commandant of the School.

In September 1927, Andrews entered the Air Corps Tactical School at Langley Field in Virginia. Upon graduation in June 1928, he remained at Langley, where he served with the 2nd Wing Headquarters until July 16, 1928. He then attended the Command and General Staff School at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas. After graduation in June 1929, he was assigned to duty in the Office of the Chief of the Air Corps in Washington, D.C. There he was promoted to lieutenant colonel on January 13, 1930. Andrews served as the chief of the Army Air Corps' Training and Operations Division for a year before taking command of the 1st Pursuit Group at Selfridge Field, Michigan. He served in this office until August 15, 1932, when he entered the Army War College in Washington, D.C.

After graduation from the Army War College in 1933, Andrews returned to the General Staff in 1934.

On October 10, 1934, he returned to duty with the War Department general staff and served its Operations and Training Branch. This was a very important period in his career for he participated in the reorganization of the Army Air Corps and in the planning for the establishment of the Army General Headquarters Air Force.

This was a turning point for the Air Corps, for the GHQ Air Force within the Army was an operating air arm. He was named the Acting Commanding Officer of the GHQ Air Force until February 28, 1935. Then on March 1, 1935 he became its Commanding General when he was appointed to the temporary rank of Brigadier General, being selected over 12 senior colonels and lieutenant colonels. He established the headquarters of the new independent strategic striking force at Langley Field in Virginia.

As the first commander of the GHQ Air Force, Andrews was also the organizer of that command and he selected the most energetic of the airpower enthusiasts in uniform for his staff. They were dedicated and purposeful airmen who believed in developing the capabilities of large bombers and were willing to put up with the frustrations of their mission. The new organization was the first American approach to independent air operations. By the creation of this new organization, the Army Air Corps was taken away from the scattered control of nine Corps Area commanders and concentrated under one head, making it a highly centralized combat unit, as had been recommended by the famous Baker Board the year before.

Theoretically, Andrews command was a concentrated striking force of all types of military aircraft. Before, the tactical units of the Air Corps had been scattered all over the U.S. under many general officers and no plans existed for this mass employment. Andrews welded these dispersed squadrons into small but efficient fighting forces of three wings: the Atlantic Wing based at headquarters at Langley Field in Virginia; the Pacific Wing at Hamilton Field in California; and the Southern Wing at Fort Crockett in Texas. Later this Southern Wing was moved to Barksdale Field in Louisiana.

He trained this striking force to concentrate rapidly on various airfields along the vast perimeter of the continental U.S. At first, secret mass flights were conducted across the continent. In later maneuvers, bombardment aviation ranged far out to sea to intercept simulated enemy task forces. All of this brought questions from the press, but they found no sensationalism in Andrews' sober modesty. He said "We must realize that in common with the mobilization of the Air Force in this area, the ground arms of the Army would also be assembling, prepared to take a major role in repelling the enemy.---I want to ask that you do not accuse of trying to win a war alone."

On December 26, 1935, Andrews was promoted to the temporary rank of major general. For the next four years, he continuously studied how to improve the GHQ Air Force and how to make it a striking force that could be ordered to any point in the world for effective action.

By now he had become an ardent supporter of the big bomber. He also personally helped to demonstrate their utility on August 24, 1935, when he piloted a Martin B-12 seaplane with 1,202.3 and 2,204.6 pound payloads to new 1,000 kilometer closed-course records. He also had a zest for flight in rain, storm and fog and made hundreds of instrumental flights and landings to prove their practicality under such conditions.

On June 29, 1936 Andrews and Major John Whitely and their crew established an international airline distance record for amphibians by flying a Douglas YOA-5 amphibian powered by two Wright Cyclone 800 horsepower engines from San Juan, Puerto Rico to Langley Field, Virginia, a distance of 1,430 miles, which was officially recognized by the National Aeronautic Association and the Federation Aeronautique Internationale. When urged to give up flying after this he said "I don't want to be one of those generals who die in bed."

In April 1937, Andrews was rated as a command pilot and combat observer. By now he had become an ardent support of the new long-range, four-engine Boeing YB-17A Flying Fortress bomber, the first of which had been delivered to the 2nd Bombardment Group at Langley Field on March 1, 1937. On October 9, 1937, he pleaded for more and bigger bombers and said "Air attacks cannot be stopped by any means now known. The main reliance to defeat an enemy air force must be bombardment aviation directed against his bases and airplanes on the ground. The airpower of a nation is what is actually in the air today; that which is on the drawing board---cannot become its airpower until five years from now, --- too late for tomorrow's employment."

Andrews was always eager to take advantage of any war game to give tactical training to his bombardment units. These were exercises with aircraft bombing land targets and then targets towed by naval vessels. He used every other opportunity to demonstrate the capabilities of big bombers. One demonstration of the B-17's capabilities came on February 27, 1938 when six from the 2nd bombardment group, led by Colonel Robert Olds, made a 5,225 mile Goodwill Flight from Miami, Florida to Buenos Aires, Argentina with a stop en route to Lima, Peru. They then returned to Langley Field, Virginia.

The first leg of the trip was the longest Air Corps mass flight to date and took 33-1/2 hours. The return flight took 33-3/4 hours. Then in August, 1938, the first B-15 bomber, powered by four 1,000 horsepower engines was delivered to the 2nd Bombardment Group. Later, one made history by flying from Langley Field to Chile in 29 hours 53 minutes carrying 3,250 pounds of medical supplies aboard for earthquake victims.

With the clouds of war darkening over Europe, Andrews fought very hard for a stronger American Air Force, particularly one fully equipped with heavy bombers. On January 16, 1939, he told members of the National Aeronautic Association at their annual convention in St. Louis that the U.S. was a fifth or sixth rate air power. Though more tactful than his hero Billy Mitchell, he was also equally persistent and told a supposedly secret session of the House of Representatives "To ensure against air attacks being launched from any of these bases (in the Caribbean and in South America)---they must be kept under constant surveillance---and we must be ready to bomb such installations as they are discovered. If the situation is sufficiently vital to require it, we must be prepared to seize these outlying bases to prevent their development by the enemy as bases of operation against us."

This statement found its way into the press and Andrews was publicly censured by the President of the U.S. who said that these views were "not those of the White House or the nation." Five years later, such a statement would be viewed as one required by "Hemisphere Defense." However, his endorsement of such a policy did not please most of the members of the Army General Staff, who still believed that Army aviation should be nothing more than "the eyes of the artillery." Consequently, when his tour as commander of the GHQ Air Force ended in March 1939, he was reverted to his permanent rank of colonel and was ordered to Ft. Sam Houston, Texas as Air Officer of the Eighth Corps Area, --- the same post that his mentor, Colonel Billy Mitchell, had been exiled ten years before.

Fortunately, Andrews had important friends who believed in him, his abilities, and the scope of his knowledge and the breadth of his experiences. He had previously taken General George C. Marshall on a tour of aircraft plants and the three bases of the GHQ Air Force and had succeeded in winning him over as a new ally for the cause of airpower. Consequently, when General Marshall was appointed as Chief of Staff of the Army, he selected Andrews to serve the War Department General Staff in Washington, D.C. as Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations and Training (G-3). He also promoted him to the permanent rank of Brigadier General in the regular army on July 1, 1939. He thus became the first airman to handle the Regular Army's organization and training programs.

Marshall's choice was based on the knowledge that Andrews was not only a distinguished military aviator, but that he was also highly skilled in international relations. In addition, he was fully versed in the classic management of ground warfare, and the only American officer with experience in the command of a balanced and integrated air arm.

In Andrews he saw the emergence of a new kind of Army leader in American History, ---one with a knowledge of airpower at the command level and a depth of general staff experience,---qualities not then common among ground or air officers. In October 1940, he was promoted to the temporary rank of major general.

After the outbreak of World War II in Europe in September 1939, the importance of the Panama Canal connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and the entire Caribbean area and their adequate defense became a matter of great concern to the War Department. Among the measures taken to strengthen the defenses in this area was the appointment by President Roosevelt of Andrews as Commander of Panama Air Force on November 14, 1940.