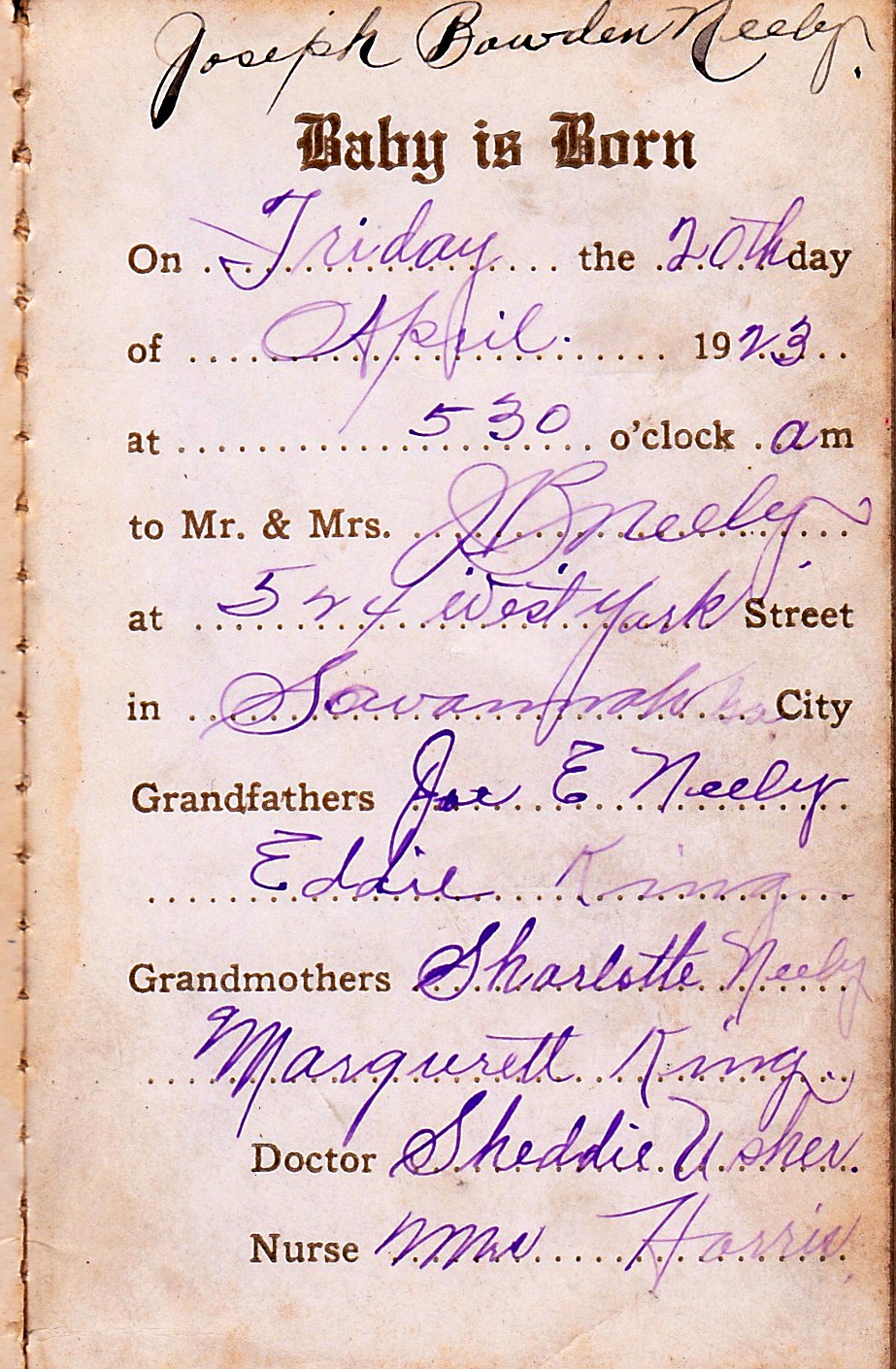

She married Joseph E. Neely, and they had five children: Joseph Bowden Neely, Sr., Ada Catherine Neely Young (the twin of Oliver Neely who died in infancy), Ruth Beatrice Neely Wink Rogers, and a fifth child, possibly named Jane Neely. Her only surviving son is named for both her husband, Joseph, and one of her brothers, Bowden Sarvis, who died in a sawmill fire.

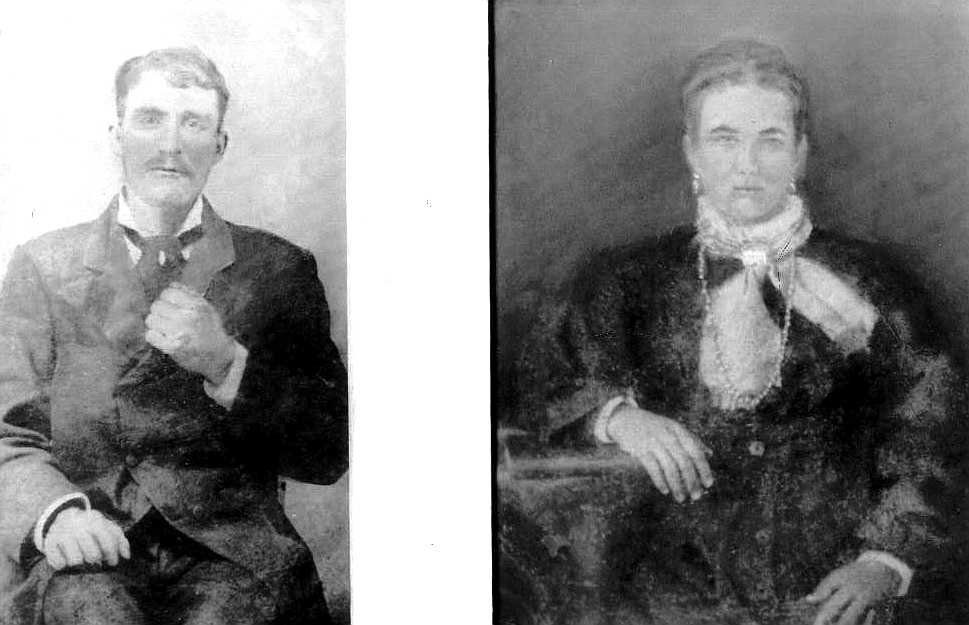

Sharlotte and her husband are probably buried in unmarked graves in the Pleasant Meadow Baptist Church Cemetery in Horry County near her Sarvis relatives. Where, when, and how did she die? Sharlotte and Joe appear in the 1900 Horry County, South Carolina census but are not on any 1910 census suggesting they both died between 1900 and 1910.

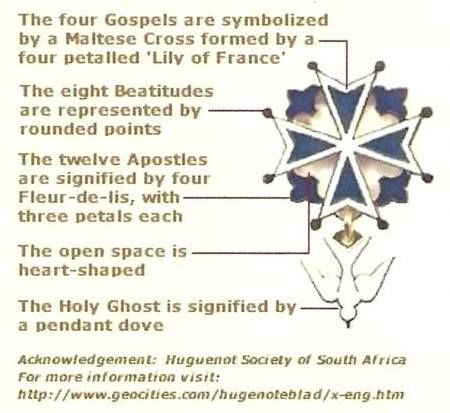

Through both her mother and father, Sharlotte was of French Huguenot and English descent. Sarvis is a coastal Carolina Native American surname. In this case, however, the Sarvis surname may have originally been Serivens, a French Huguenot name. Her granddaughter Charlotte Wink was named for her. Her great-granddaughter Sharlotte Neely Donnelly is named for her.

There are a variety of reasons Native American (American Indian) ancestry may not show up in a person's DNA. One obvious reason is that a person may never have had any Native American ancestors. There are, however, other reasons. For most Americans with Native American ancestors, that ancestry is five or more generations back. In fact it can be so far back in a family tree that it does not show up in DNA tests. Also, most ancestry testing companies use only a small sample of Native American groups (often less than half a dozen tribes) as a reference for testing, and many of those sample groups are from South, rather than North, America. (My own case is a good example of how inaccurate genetics testing companies can be when it comes to Native American ancestry. Three different companies have estimated my Indian ancestry as none, a trace, and 9%.) Another important point about American Indian (Native American) DNA ancestry should be made. Anthropologist Mary Helms created the term "colonial Indian tribes" in the 1960s to refer to societies which originated as recognizable entities only as a direct result of colonial policies. Colonial tribes are often a racially mixed people that over time became identified more with their Indian ancestry rather than their African or white ancestry. These groups are culturally Indian while ultimately having little, if any, Indian DNA. Colonial tribes include groups as diverse as the Miskito Indians of eastern Nicaragua (whom Helms studied); various Amazon tribes in Brazil; the Lumbee Indians of North Carolina; the Black Seminoles of Oklahoma, Mexico, and the Bahamas; and many others. The term colonial tribe attempts to get at the idea that someone can be culturally something (American Indian, for example) without being biologically something. So, it should not be surprising that someone with, for example, a Lumbee Indian ancestor would not necessarily test as having significant American Indian DNA.

Thanks so much to descendants Joseph Bowden Neely, Jr. and Kay Evans for much of this information. Any errors, however, are mine alone. Please go to the "edit" link on this site with any corrections or additions.

She married Joseph E. Neely, and they had five children: Joseph Bowden Neely, Sr., Ada Catherine Neely Young (the twin of Oliver Neely who died in infancy), Ruth Beatrice Neely Wink Rogers, and a fifth child, possibly named Jane Neely. Her only surviving son is named for both her husband, Joseph, and one of her brothers, Bowden Sarvis, who died in a sawmill fire.

Sharlotte and her husband are probably buried in unmarked graves in the Pleasant Meadow Baptist Church Cemetery in Horry County near her Sarvis relatives. Where, when, and how did she die? Sharlotte and Joe appear in the 1900 Horry County, South Carolina census but are not on any 1910 census suggesting they both died between 1900 and 1910.

Through both her mother and father, Sharlotte was of French Huguenot and English descent. Sarvis is a coastal Carolina Native American surname. In this case, however, the Sarvis surname may have originally been Serivens, a French Huguenot name. Her granddaughter Charlotte Wink was named for her. Her great-granddaughter Sharlotte Neely Donnelly is named for her.

There are a variety of reasons Native American (American Indian) ancestry may not show up in a person's DNA. One obvious reason is that a person may never have had any Native American ancestors. There are, however, other reasons. For most Americans with Native American ancestors, that ancestry is five or more generations back. In fact it can be so far back in a family tree that it does not show up in DNA tests. Also, most ancestry testing companies use only a small sample of Native American groups (often less than half a dozen tribes) as a reference for testing, and many of those sample groups are from South, rather than North, America. (My own case is a good example of how inaccurate genetics testing companies can be when it comes to Native American ancestry. Three different companies have estimated my Indian ancestry as none, a trace, and 9%.) Another important point about American Indian (Native American) DNA ancestry should be made. Anthropologist Mary Helms created the term "colonial Indian tribes" in the 1960s to refer to societies which originated as recognizable entities only as a direct result of colonial policies. Colonial tribes are often a racially mixed people that over time became identified more with their Indian ancestry rather than their African or white ancestry. These groups are culturally Indian while ultimately having little, if any, Indian DNA. Colonial tribes include groups as diverse as the Miskito Indians of eastern Nicaragua (whom Helms studied); various Amazon tribes in Brazil; the Lumbee Indians of North Carolina; the Black Seminoles of Oklahoma, Mexico, and the Bahamas; and many others. The term colonial tribe attempts to get at the idea that someone can be culturally something (American Indian, for example) without being biologically something. So, it should not be surprising that someone with, for example, a Lumbee Indian ancestor would not necessarily test as having significant American Indian DNA.

Thanks so much to descendants Joseph Bowden Neely, Jr. and Kay Evans for much of this information. Any errors, however, are mine alone. Please go to the "edit" link on this site with any corrections or additions.

Family Members

-

![]()

PVT Thomas Lester "Tommy" Sarvis

1847–1931

-

![]()

PVT William Scarborough Sarvis

1848–1862

-

![]()

George Marsden Sarvis

1850–1871

-

![]()

Edward Charles "Ned" Sarvis

1851–1927

-

![]()

Helan Sarvis King

1852–1918

-

![]()

Rhoda Mary Elizabeth "Lizzie" Sarvis Cartrette

1854–1934

-

![]()

Eahmon A. Sarvis

1858–1871

-

![]()

Bowden Sarvis

1859–1871

-

![]()

Dock J Sarvis

1861–1931

-

![]()

James Scarborough Sarvis

1862–1919