Lawyer, Author, Roman Catholic Saint. One of the key figures of the English Renaissance. His humanist political fantasy, "Utopia" (1516), has had an enduring impact on world literature and social theory. A loyal Catholic, More served as Lord Chancellor of England under Henry VIII (1529 to 1532) but resigned because he opposed the king's religious policies. This stance cost him his life. He is admired for his steadfast courage in putting his conscience above the demands of secular authority. G. K. Chesterton wrote that "the mind of More was like a diamond that a tyrant threw away into a ditch because he could not break it." More was born in London, the son of Sir John More, a respected lawyer and judge. He attended St. Anthony's School in Threadneedle Street and served as a page for Cardinal John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor, who sent him to Oxford University's Christ Church in 1492. At his father's insistence, he studied law at New Inn (1494 to 1496) and Lincoln's Inn, gaining admission to the bar in 1501. While continuing to pursue classical interests, he came to know several eminent scholars, forming lifelong friendships with John Colet and Desiderius Erasmus. He mastered Latin, Greek, mathematics, history, and astronomy, learned to play several musical instruments, and wrote poetry. More's first substantial literary work, an English translation of a biography of Catholic humanist philosopher Pico della Mirandola (1505), reflected a period when he seriously considered taking Holy Orders. Between 1499 and 1503, he delivered a series of lectures on St. Augustine's "City of God" and was drawn to the austere devotion of the Carthusian and Franciscan monks. According to Erasmus, "The one thing that prevented him from giving himself to that kind of life was that he could not shake off the desire of the married state. He chose, therefore, to be a chaste husband rather than an impure priest." Like Pico della Mirandola, he also decided that his abilities would be of greater use in the secular world, but part of him would always remain a religious ascetic. Even at the height of his political power, he wore a hair shirt beneath his robes and practiced self-flagellation and other forms of penance. In January 1505, More married 16-year-old Jane Colt, the daughter of a nobleman. They had four children and adopted an orphan named Margaret Giggs. Within a month of Jane's death in 1511, he married the widow Alice Middleton to manage his household and raised her daughter as his own. He supported his family through his exceptional skills as a lawyer both in civil cases and international trade negotiations. Despite his youth, he was invited to serve as Reader (senior lecturer) at Furneval Inn from 1504 to 1507 and won much respect for providing pro bono services to the poor. This led to his first election to Parliament in 1504, when he was 25. At that time Henry VII was notorious for using the assembly as a rubber stamp for his exorbitant tax policies, carried out by royal ministers Edmund Dudley and Sir Richard Empson. Dudley served as Speaker of the House for that session and sought a huge appropriation based, rather dubiously, on ancient feudal privileges. To his surprise, More led an opposition group that succeeded on legal grounds in reducing the amount by two-thirds. Henry was furious that "a beardless boy" in the House of Commons had put such a dent in his coffers and would not summon Parliament again for the rest of his reign. Dudley later told More that he escaped beheading only because he had prudently avoided mentioning the king's name in his speeches. Instead, the monarch retaliated against More's father, tossing him in prison on a petty trumped-up charge until he paid a fine of 100 pounds. Some believe More visited universities in France and Flanders in 1508 to investigate the possibilities of self-exile. The 18-year-old Henry VIII ascended to the throne the following year and announced a change in policy by removing the unpopular Dudley and Empson from power (both were subsequently executed). More celebrated these events by writing a "Coronation Ode" (1509) that combined the flattery of the new king with a surprisingly frank condemnation of his father's rule. From then on, his public career rose steadily. He was reelected to Parliament in 1509, but his ambition was now tempered by a reluctance to enter royal service. He would never trust kings and would learn well the value of silence as a personal legal strategy. From 1510 to 1518, More served as Undersheriff of London, gaining a reputation as a fair, incorruptible judge. His heroic, if unsuccessful, attempt to peacefully circumvent the "Evil May Day" race riot (1517) was long remembered in the city. He was also peripherally involved in the 1514 investigation of Richard Hunne, a Lollard sympathizer imprisoned and murdered for waging an unprecedented lawsuit that challenged Catholic intervention in civil affairs. Future Protestants would cite the case as an example of the injustices that made the English Reformation inevitable. In a letter to Erasmus, More complained that his duties as Undersheriff prevented him from doing much creative writing, but his two most important books emerged from this period. "The History of Richard III" (c. 1513), based on unpublished material by Cardinal Morton, is naturally biased towards the Tudors. More was the first historian to portray the Plantagenet king as a scheming, villainous usurper, stopping short of blaming him for the deaths of the Duke of Clarence and the Princes in the Tower while making it clear he was capable of such deeds. Its dramatic and literary quality marked a step forward in English biography, especially More's ability to capture the essence of a scene with a single telling detail. He never finished it, probably because a few of Richard's key associates were still living. Manuscript copies circulated for decades and, from the 1540s, began to appear in English histories, including Holinshed's "Chronicles" (1587), the primary source for Shakespeare's play "Richard III." In 1515, More spent six months in Flanders as part of a delegation reviewing disputes over the wool trade, a task that gave him the leisure time to write Book II of "Utopia." Book I was completed in London the following year. Erasmus supervised its original publication at Louvain. Written in Latin, it made More famous throughout Europe, though he would not allow it to be published in England during his lifetime. A dialogue in the book reveals him contemplating the efforts of Henry VIII and Cardinal Thomas Wolsey to secure his services at court, with its rewards and deadly intrigues. On the subject of statesmanship, he reasoned, "You must not abandon the ship in a storm because you cannot control the winds...What you cannot turn to good, you must at least make as little bad as you can." In August 1517, More finally became a member of the Privy Council, enjoying remarkable royal favor for someone of common birth. From 1519, he was a vital intermediary between Wolsey and the king, accompanying both to the summit meeting between England and France at the Field of the Cloth of Gold (1520). He was knighted in 1521 for a successful diplomatic mission in Bruges, receiving land grants in Oxford and Kent as additional rewards. Among his many appointments were those of Under Treasurer of the Exchequer (1521 to 1525), Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (1525 to 1529), and High Steward of Oxford and Cambridge Universities (from 1525). In 1523, More agreed to serve as Speaker of the House of Commons on the condition that its members were permitted freedom of speech, a landmark event in the history of Parliament. He capped his diplomatic career by helping negotiate the Treaty of Cambrai (1529), a truce between Francis I of France and the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, with benefits to English foreign trade. The onetime aspiring monk enjoyed the trappings of wealth, moving into a 34-acre estate along the River Thames in Chelsea. Later, he built a private chapel at Chelsea Old Church, where he and his family worshipped. His patronage of the arts brought painter Hans Holbein the Younger to England in 1526, beginning an association that would yield some of the greatest portraits of the Tudor era, including the iconic 1527 likeness of More himself. At home, he was both a quietly stern and affectionate patriarch. Most unusual for that era was his interest in women's education, an idea he first broached in "Utopia." He saw to it that his five daughters were as well-instructed in the classics as his son and insisted they correspond with him in Latin. His favorite child. Margaret (he called her Meg), became the most learned Englishwoman of her day. To all, he was known for a quick and ironic wit that never deserted him under any circumstances, causing humor-impaired observers to wonder if he took anything seriously. In the early Chelsea years, King Henry liked to visit unannounced, and he and More would chat for hours in the garden, his arm around More's shoulder in a privileged gesture of royal familiarity. Flattering as it appeared to others, More had no illusions about this "friendship." He confided to Margaret's husband, William Roper, "If my head would win him a castle in France, it should not fail to go." In the end, it was an epochal clash of religion and politics that brought him to that fate. More started out as a conservative Christian humanist, using humor and speculation in his writings to suggest the need for reform within the church. The freer-thinking Erasmus wrote his famous satire of monks and the papacy, "The Praise of Folly" (1509). For More's amusement, its Latin title, "Moriae Encomium," was a pun on his name ("The Praise of More"). High-spirited ridicule of dense clergymen can be found in "Utopia" and in More's "Epigrammata" (1518), but in many respects, he was still a Medieval man in his attitude. He never wavered in his devout Catholicism, and the rise of the Protestant movement in the 1520s drove him to defend his faith with a reactionary zeal that some historians have characterized as a betrayal of his humanist principles. It began with Henry's repudiation of Martin Luther in his "Defence of the Seven Sacraments" (1521), allegedly written with More's help. When the Protestant leader fired back in a crudely insulting pamphlet, More replied on Henry's behalf with the even cruder "Response to Luther" (1523). More believed the only stabilizing influence in a splintered and constantly warring Europe was the Catholic hierarchy. For him Luther was a false prophet; the Reformation, the Antichrist that threatened to plunge Western civilization into anarchy. He laid responsibility for the German Peasants' Revolt (1525 to 1526) at Luther's door. More went on to wage a polemical war against the exiled William Tyndale, the first translator of the Bible into English, in "A Dialogue Concerning Heresies" (1529) and the vast "Confutation of Tyndale's Answer" (1532). At root was the fear that making the Old and New Testaments available in the vernacular would lead to independent interpretations and the erosion of Catholic teaching. "The Supplication of Souls" (1529) brought him into conflict with Tyndale's ally Simon Fish and dissident priest John Frith. Filled with scorn and mounting hatred, these works show that More was not above using base propaganda methods to uphold the Church. Thus in 1527, when Henry embarked on his "great matter" - his determination to annul his union with Catharine of Aragon, which had failed to produce a male heir, and marry Anne Boleyn - he and More were set on a collision course. Wolsey's failure to procure the annulment from the Holy See resulted in his dismissal on October 17, 1529, and, on October 26, More was named new Lord Chancellor. The choice was surprising since More had told Henry he believed in Catherine's legitimacy as queen; perhaps it was felt that as a loyal servant, he would eventually change his mind. He accepted the appointment primarily because he hoped to enact tougher laws against the spread of Lutheranism, unaware that the king's fury at the Pope for standing in his way would open the floodgates of the English Reformation. Along with the outspoken Bishop of Rochester, John Fisher, More became the most visible leader of the English Catholic opposition. During his chancellorship, six Protestants were burned at the stake as heretics, and dozens more were arrested, some dying in prison; the fugitive Frith was seized on a warrant issued by More and put to death in 1533. In "The Apology of Sir Thomas More" (1533), he defended himself by stating he was duty-bound to enforce England's civil laws, including the use of capital punishment against religious dissidents, and emphatically denied rumors he tortured suspects under interrogation. Not only was More swimming against the tide, but his downfall had begun within weeks of his taking office. The first session of the Reformation Parliament (November 1529 to April 1536) initiated Henry's break from Rome. In 1530, More refused to sign a petition to have Pope Clement VII annul Henry's marriage, and the following year, he asked to step down rather than take an oath declaring the king supreme head of the English Church with the proviso "as far as the law of Christ allows." His request was denied. A formidable new enemy, the Reformist Thomas Cromwell, gained entry to the royal inner circle and began whittling away at the power of the bishops (and More) through Parliamentary bills, including limiting the persecution of Protestants. On May 15, 1532, the clergy yielded to Henry's demand that all religious law in England required royal consent. More resigned as Lord Chancellor the next day, citing a heart condition, unable to tolerate further incursions into Catholic authority. Aware that his position was now dangerous, he prepared himself and his family for the likelihood of his arrest. His first act on leaving office was to erect his intended tomb at Chelsea Old Church, its epitaph proudly noting that he was "troublesome to thieves, murderers, and heretics." He did not actively seek martyrdom. He hoped to avoid the royal displeasure by keeping silent about Henry's 1533 annulment from Catherine and marriage to Anne, both performed in defiance of Rome by the accommodating new Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer and for which Henry and Cranmer were excommunicated. More's conspicuous absence at Anne's coronation was noted - he was too high-profile for so much as passive resistance to go unchecked. Cromwell hounded him with investigations, and in February 1534, he was included in a bill of attainder for alleged complicity with the "Nun of Kent" Elizabeth Barton, who had predicted Henry's death and damnation for rejecting the papacy. More admitted interviewing Barton, then managed to escape the charges by producing a letter in which he warned her to keep out of state affairs. On March 23, 1534, Parliament passed the Act of Succession, which established the line of succession through the children of Queen Anne. It also required English subjects to take an oath vowing to uphold the Act and recognize the king's supremacy over "all foreign princes and potentates" (including the pope). Failure to do so when commanded was considered high treason. On April 13, More was summoned to Lambeth Palace to pledge his allegiance to the Act. After reading the texts, he told the commission that while he accepted the right to declare Anne queen, he would not swear to the oath nor explain his refusal. He was remanded to the custody of the Abbot of Westminster and, on April 17, was transported to the Tower of London, where Bishop John Fisher was already being held for taking the same stand. During his 15 months in prison, he wrote his finest religious work, "A Dialogue of Comfort Against Tribulation" (1534), as well as letters to Margaret attempting to explain himself without incriminating either of them; she alone of his loved ones sympathized with his actions. That same period saw the passage of two laws that would lead directly to More's execution: the Act of Supremacy, which formally established Henry as head of the English Church, and the Treason Act, a blanket law that made mere criticism of the king's policies punishable by death. The latter was clearly intended to deal with men like More who posed obstacles to the Reformation. Cromwell visited him several times, demanding to know his thoughts on these acts and promising leniency if he cooperated. More continued to stonewall, saying he had given up "meddling" in worldly affairs and only wanted to lead a good Christian life. On June 22, 1535, John Fisher was executed. Days earlier, the bishop had been found in possession of smuggled letters from More, and Solicitor General Richard Rich was sent to confiscate More's books and writing materials. On that occasion, he and Rich had a seemingly casual discussion that would be manipulated into the principal charge against him. More was tried for treason at Westminster Hall on July 1, 1535. He had no chance of winning acquittal: the panel of judges included Anne Boleyn's father, brother, and uncle, and was led by new Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley, who would keep his head through utter subservience to Henry's will. The jury faced possible reprisals if they sided with the defendant. Nevertheless, he conducted a brilliant defense, the culmination of 40 years' worth of legal experience and study. Visibly frail and wearing a long gray beard, More remained seated throughout, but answered the charges in a firm voice. He had indeed, "according to the dictates of my conscience," expressed opposition to Henry's annulment and remarriage - as a private opinion the king had specifically asked for, which did not constitute treason. To lie under the circumstances would have been a greater sin to both God and sovereign, he maintained. On his failure to swear the oath recognizing the king as leader of the English Church, the judges asserted that More's refusal to divulge his motives was proof of malicious intent. "No law in the world can punish any man for his silence," More countered, citing benefit of the doubt through the legal maxim "qui tacet consentire videtur" ("who is silent is seen to consent"). The third count alleged that in his prison correspondence with Fisher, More tried to persuade the bishop to violate the Treason Act. The letters could not be entered as evidence (it was claimed Fisher had burned them), enabling More to refute the charge as false hearsay. The court then called Richard Rich, who testified that, during their conversation in the Tower, More had, in fact, denied Henry as head of the church. Rich had previously sealed Fisher's doom by persuading him, under false pretenses, to give his honest opinion on the Act of Supremacy, but it is unlikely More would have fallen into the same trap. The accused told the panel he shared his thoughts on the matter with no one and would certainly not have done so with Rich, whom he described as having a reputation for low moral character. If the Solicitor General's account was true, he added, "then I pray I may never see God's face." The two men who accompanied Rich to the Tower were called to corroborate his testimony, but both insisted they were too busy removing More's possessions to hear what was being said. With that, the case was handed over to the jury. They returned with a guilty verdict in 15 minutes. Before sentence was passed More reminded the court that he was entitled to a final "arrest of judgement" statement, and with nothing left to lose he spoke his mind at last, challenging the legality of the proceedings. He stated that his indictment was grounded on a law "directly oppugnant to God." No "temporal prince" could usurp religious leadership from the See of Rome, and Parliament had no right to enact legislation that conflicted with the laws of "Christ's universal Catholic Church." He also explained how provisions in the Succession and Treason Acts negated centuries of English legal precedent, including the Magna Carta. When Audley asked how he alone could defy what "the best learned of this realm" had agreed to support, More replied tha,t outside of England, the view would be the opposite. "I am not bound, my lord, to conform my conscience to the council of one realm against the General Council of Christendom." He concluded, "I shall pray heartily that though your lordships have now here on Earth been judges of my condemnation, we may yet hereafter in heaven merrily all meet together to everlasting salvation." More was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn, the punishment for commoners convicted of treason. Henry commuted the sentence to beheading, supposedly in gratitude for his years of loyal service; he also commanded that the prisoner "not use many words" on the scaffold. The execution took place at London's Tower Hill on July 6, 1535. Before the axe fell, More implored the spectators to bear witness that he died "the king's good servant, and God's first." His body was unceremoniously buried beneath the floor of the nearby Chapel of Saint Peter ad Vincula, to rest with other victims of Henry's wrath (soon to include Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell). More's head was displayed on a pike above London Bridge for a month before his daughter, Margaret Roper, clandestinely rescued it from being tossed into the Thames. When she died in 1544, the skull was buried with her at Chelsea Old Church, in the tomb More had wished to occupy. The remains of both were later reinterred in the Roper Vault at St. Dunstan's Church in Canterbury. News of More's death shocked Continental Europe, where he was regarded as a foremost intellectual. Charles V told the English ambassador, "If I had been master of such a servant...I would rather have lost the best city in my dominions than lose such a worthy councilor." His reputation remained high in England over the backlash of the evangelicals he fought against; even his enemies did not appear to believe he was a traitor, tacitly acknowledging that his execution was an act of judicial murder. Protestant polemicist John Foxe demonized him as "a bitter persecutor of good men" in his "Book of Martyrs" (1563), but granted that, in matters outside of religion, he was "in degree worshipful, in place superior, in wit and learning singular...a man with many worthy ornaments beautified." Anglican author Jonathan Swift called More "a person of the greatest virtue this kingdom ever produced" for sacrificing his life for his beliefs. More and Fisher were beatified by Pope Leo XIII in 1886, and, in 1935, they were canonized by Pope Pius XI, with their feast day on June 22., the anniversary of St. John Fisher's death. In 1980, the Church of England recognized More as a "Reformation martyr" and included him in its Calendar of Saints (July 6). A 1999 poll from the Law Society of Great Britain voted him "Lawyer of the Millenium" over Abraham Lincoln, Mohandas Gandhi, and Nelson Mandela. Having already been named patron saint of attorneys, More was declared "the heavenly patron of statesmen and politicians" by Pope John Paul II in 2000. He was depicted as the idealized hero of conscience in Robert Bolt's 1960 play "A Man for All Seasons" (and its 1966 film adaptation). More was certainly a complex, contradictory man. The same can be said for his masterpiece "Utopia," a work that spawned two literary genres and has influenced political and philosophical thought for centuries. In this imaginative quest for the best possible form of government, More coined the term "Utopia" by combining two Greek words that together mean "no place." His models were Plato's "Republic" (c. 380 BC) and the New World adventures chronicled in "The Four Voyages of Amerigo Vespucci" (published in 1507). The setting is Antwerp during More's 1515 stay in the Low Countries, and the author is a main character. In Book I, he meets veteran traveler Raphael Hythloday, whose exploits include sailing with Vespucci on his last voyage. Hythloday's surname translates as "dealer in nonsense," but he impresses More with his insightful criticisms of the many ills and injustices of European society, England in particular. When More urges him to use his knowledge to benefit mankind by serving as advisor to a monarch, he claims he lacks diplomatic skills and that royal courts are too corrupt to listen to him anyway. He then mentions that he has discovered the ideal commonwealth on a remote island in the Western Hemisphere, and, in Book II, he describes it in great detail. The nation of Utopia is an intricate form of democracy consisting of 54 cities, each ruled by an elected official called a Prince; this is a lifetime position, but the leader can be voted out of office for abuse of power. Money and private property are unknown, as all material needs are supplied for free by the state. It has six-hour workdays, universal healthcare and education, and almost complete religious freedom (atheists are rather grudgingly tolerated). Utopians view war as immoral and hire mercenaries to do their necessary fighting for them. Citizens are required to spend two years working on communal farms for a fair share of agricultural labor; after that they are given employment best suited to their abilities. Engaged couples are allowed to see each other naked to get a better idea of who they are going to spend the rest of their lives with, and consensual divorce for incompatibility is permitted. Euthanasia is a legal option. There are no locked doors, no poverty or hunger, no violent crime. Most tantalizing of all, there are no lawyers, the laws being few and simple enough for the layman to understand. But Utopia is not as ideal as Hythloday insists we believe. It is a severely-regimented society with little privacy or individual freedom. Everyone wears the same clothes, eats the same food, and lives in identical housing. Families are periodically reassigned living quarters to prevent them from gaining roots in one place, or are relocated to other parts of the island to keep the populations of its cities as equal as possible. The few opportunities for personal choice, such as dining at home instead of at a communal hall, are socially frowned upon. There are no taverns or "secret meeting places" to indulge bad habits or ideas, and while the people have much more leisure time, the place seems dreadfully dull. Hythloday rationalizes such enforced conformity because, in Utopia, the negative impulses of human nature are controlled for the common good; he claims the Utopians are contented. In the end, More is skeptical. He admits he would like to see certain elements of Utopia implemented in England but doubts it will ever happen. The insoluble enigma of "Utopia" is More's own viewpoint. Did he intend it to be a serious political manifesto? A satire? A cunning plea for a Catholic theocracy? Nothing in the book can be taken at face value, but the concept of Utopia was so convincingly presented that attempts to reproduce it in life and art began during More's lifetime. The first communities based on utopian principles were founded in Mexico (then part of New Spain) in the early 1530s by Catholic bishop and jurist Vasco de Quiroga, as a means of converting the indigenous population to Christianity and a Spanish way of life. More's book also influenced pioneer socialists Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and Robert Owen, whose theories led to the founding of several short-lived utopian villages in the American Midwest during the mid-1800s. Such experiments were rejected as impractical by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in "The Communist Manifesto" (1848), in which they introduced the term "Utopian socialism" to distinguish lofty speculation on socialist ideals from their own "scientific socialism," which advocated revolutionary action. The 20th Century Israeli kibbutz successfully originated in the utopian organization. In the world of letters, the book's progress was steadier. It was translated into German (1524), Italian (1548), French (1550), English (by Ralph Robinson, 1551), Dutch (1553), and Spanish (1637), while the word "utopia" itself entered standard usage in those languages. In 1532, the French satirist Rabelais referred to the Utopians in the first volume of his "Gargantua and Pantagrue, l" and, in the 17th century, writers began to foster utopian literature by creating their own fictional commonwealths. Notable among these are Tommaso Campanella's "The City of the Sun" (1623), Francis Bacon's "The New Atlantis" (1624), Edward Bellamy's "Looking Backward" (1888), and William Morris' "News from Nowhere" (1891). Swift's classic "Gulliver's Travels" (1726) presents a series of satirical Utopias. H. G. Wells explored the theme in several books, among them "The Time Machine" (1895), "A Modern Utopia" (1905), and "The Shape of Things to Come" (1933). In 1868, John Stuart Mill invented the term "dystopia" ("bad place") to describe nightmare visions of the future, though as a genre it did not become prevalent until the 20th century, spurred by two World Wars and the rise of Communism. Key examples of dystopian fiction include Yevgeny Zamyatin's "We" (1924), Aldous Huxley's "Brave New World" (1932), George Orwell's "1984" (1949), Ray Bradbury's "Fahrenheit 451" (1953), Anthony Burgess' "A Clockwork Orange" (1962), Ursula K. Le Guin's "The Lathe of Heaven" (1971), and Margaret Atwood's "The Handmaid's Tale" (1985). Many works of science fiction in different media employ utopian or dystopian forms.

View body burial: Burial Location with family links.

View head burial: Head Here.

Lawyer, Author, Roman Catholic Saint. One of the key figures of the English Renaissance. His humanist political fantasy, "Utopia" (1516), has had an enduring impact on world literature and social theory. A loyal Catholic, More served as Lord Chancellor of England under Henry VIII (1529 to 1532) but resigned because he opposed the king's religious policies. This stance cost him his life. He is admired for his steadfast courage in putting his conscience above the demands of secular authority. G. K. Chesterton wrote that "the mind of More was like a diamond that a tyrant threw away into a ditch because he could not break it." More was born in London, the son of Sir John More, a respected lawyer and judge. He attended St. Anthony's School in Threadneedle Street and served as a page for Cardinal John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor, who sent him to Oxford University's Christ Church in 1492. At his father's insistence, he studied law at New Inn (1494 to 1496) and Lincoln's Inn, gaining admission to the bar in 1501. While continuing to pursue classical interests, he came to know several eminent scholars, forming lifelong friendships with John Colet and Desiderius Erasmus. He mastered Latin, Greek, mathematics, history, and astronomy, learned to play several musical instruments, and wrote poetry. More's first substantial literary work, an English translation of a biography of Catholic humanist philosopher Pico della Mirandola (1505), reflected a period when he seriously considered taking Holy Orders. Between 1499 and 1503, he delivered a series of lectures on St. Augustine's "City of God" and was drawn to the austere devotion of the Carthusian and Franciscan monks. According to Erasmus, "The one thing that prevented him from giving himself to that kind of life was that he could not shake off the desire of the married state. He chose, therefore, to be a chaste husband rather than an impure priest." Like Pico della Mirandola, he also decided that his abilities would be of greater use in the secular world, but part of him would always remain a religious ascetic. Even at the height of his political power, he wore a hair shirt beneath his robes and practiced self-flagellation and other forms of penance. In January 1505, More married 16-year-old Jane Colt, the daughter of a nobleman. They had four children and adopted an orphan named Margaret Giggs. Within a month of Jane's death in 1511, he married the widow Alice Middleton to manage his household and raised her daughter as his own. He supported his family through his exceptional skills as a lawyer both in civil cases and international trade negotiations. Despite his youth, he was invited to serve as Reader (senior lecturer) at Furneval Inn from 1504 to 1507 and won much respect for providing pro bono services to the poor. This led to his first election to Parliament in 1504, when he was 25. At that time Henry VII was notorious for using the assembly as a rubber stamp for his exorbitant tax policies, carried out by royal ministers Edmund Dudley and Sir Richard Empson. Dudley served as Speaker of the House for that session and sought a huge appropriation based, rather dubiously, on ancient feudal privileges. To his surprise, More led an opposition group that succeeded on legal grounds in reducing the amount by two-thirds. Henry was furious that "a beardless boy" in the House of Commons had put such a dent in his coffers and would not summon Parliament again for the rest of his reign. Dudley later told More that he escaped beheading only because he had prudently avoided mentioning the king's name in his speeches. Instead, the monarch retaliated against More's father, tossing him in prison on a petty trumped-up charge until he paid a fine of 100 pounds. Some believe More visited universities in France and Flanders in 1508 to investigate the possibilities of self-exile. The 18-year-old Henry VIII ascended to the throne the following year and announced a change in policy by removing the unpopular Dudley and Empson from power (both were subsequently executed). More celebrated these events by writing a "Coronation Ode" (1509) that combined the flattery of the new king with a surprisingly frank condemnation of his father's rule. From then on, his public career rose steadily. He was reelected to Parliament in 1509, but his ambition was now tempered by a reluctance to enter royal service. He would never trust kings and would learn well the value of silence as a personal legal strategy. From 1510 to 1518, More served as Undersheriff of London, gaining a reputation as a fair, incorruptible judge. His heroic, if unsuccessful, attempt to peacefully circumvent the "Evil May Day" race riot (1517) was long remembered in the city. He was also peripherally involved in the 1514 investigation of Richard Hunne, a Lollard sympathizer imprisoned and murdered for waging an unprecedented lawsuit that challenged Catholic intervention in civil affairs. Future Protestants would cite the case as an example of the injustices that made the English Reformation inevitable. In a letter to Erasmus, More complained that his duties as Undersheriff prevented him from doing much creative writing, but his two most important books emerged from this period. "The History of Richard III" (c. 1513), based on unpublished material by Cardinal Morton, is naturally biased towards the Tudors. More was the first historian to portray the Plantagenet king as a scheming, villainous usurper, stopping short of blaming him for the deaths of the Duke of Clarence and the Princes in the Tower while making it clear he was capable of such deeds. Its dramatic and literary quality marked a step forward in English biography, especially More's ability to capture the essence of a scene with a single telling detail. He never finished it, probably because a few of Richard's key associates were still living. Manuscript copies circulated for decades and, from the 1540s, began to appear in English histories, including Holinshed's "Chronicles" (1587), the primary source for Shakespeare's play "Richard III." In 1515, More spent six months in Flanders as part of a delegation reviewing disputes over the wool trade, a task that gave him the leisure time to write Book II of "Utopia." Book I was completed in London the following year. Erasmus supervised its original publication at Louvain. Written in Latin, it made More famous throughout Europe, though he would not allow it to be published in England during his lifetime. A dialogue in the book reveals him contemplating the efforts of Henry VIII and Cardinal Thomas Wolsey to secure his services at court, with its rewards and deadly intrigues. On the subject of statesmanship, he reasoned, "You must not abandon the ship in a storm because you cannot control the winds...What you cannot turn to good, you must at least make as little bad as you can." In August 1517, More finally became a member of the Privy Council, enjoying remarkable royal favor for someone of common birth. From 1519, he was a vital intermediary between Wolsey and the king, accompanying both to the summit meeting between England and France at the Field of the Cloth of Gold (1520). He was knighted in 1521 for a successful diplomatic mission in Bruges, receiving land grants in Oxford and Kent as additional rewards. Among his many appointments were those of Under Treasurer of the Exchequer (1521 to 1525), Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (1525 to 1529), and High Steward of Oxford and Cambridge Universities (from 1525). In 1523, More agreed to serve as Speaker of the House of Commons on the condition that its members were permitted freedom of speech, a landmark event in the history of Parliament. He capped his diplomatic career by helping negotiate the Treaty of Cambrai (1529), a truce between Francis I of France and the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, with benefits to English foreign trade. The onetime aspiring monk enjoyed the trappings of wealth, moving into a 34-acre estate along the River Thames in Chelsea. Later, he built a private chapel at Chelsea Old Church, where he and his family worshipped. His patronage of the arts brought painter Hans Holbein the Younger to England in 1526, beginning an association that would yield some of the greatest portraits of the Tudor era, including the iconic 1527 likeness of More himself. At home, he was both a quietly stern and affectionate patriarch. Most unusual for that era was his interest in women's education, an idea he first broached in "Utopia." He saw to it that his five daughters were as well-instructed in the classics as his son and insisted they correspond with him in Latin. His favorite child. Margaret (he called her Meg), became the most learned Englishwoman of her day. To all, he was known for a quick and ironic wit that never deserted him under any circumstances, causing humor-impaired observers to wonder if he took anything seriously. In the early Chelsea years, King Henry liked to visit unannounced, and he and More would chat for hours in the garden, his arm around More's shoulder in a privileged gesture of royal familiarity. Flattering as it appeared to others, More had no illusions about this "friendship." He confided to Margaret's husband, William Roper, "If my head would win him a castle in France, it should not fail to go." In the end, it was an epochal clash of religion and politics that brought him to that fate. More started out as a conservative Christian humanist, using humor and speculation in his writings to suggest the need for reform within the church. The freer-thinking Erasmus wrote his famous satire of monks and the papacy, "The Praise of Folly" (1509). For More's amusement, its Latin title, "Moriae Encomium," was a pun on his name ("The Praise of More"). High-spirited ridicule of dense clergymen can be found in "Utopia" and in More's "Epigrammata" (1518), but in many respects, he was still a Medieval man in his attitude. He never wavered in his devout Catholicism, and the rise of the Protestant movement in the 1520s drove him to defend his faith with a reactionary zeal that some historians have characterized as a betrayal of his humanist principles. It began with Henry's repudiation of Martin Luther in his "Defence of the Seven Sacraments" (1521), allegedly written with More's help. When the Protestant leader fired back in a crudely insulting pamphlet, More replied on Henry's behalf with the even cruder "Response to Luther" (1523). More believed the only stabilizing influence in a splintered and constantly warring Europe was the Catholic hierarchy. For him Luther was a false prophet; the Reformation, the Antichrist that threatened to plunge Western civilization into anarchy. He laid responsibility for the German Peasants' Revolt (1525 to 1526) at Luther's door. More went on to wage a polemical war against the exiled William Tyndale, the first translator of the Bible into English, in "A Dialogue Concerning Heresies" (1529) and the vast "Confutation of Tyndale's Answer" (1532). At root was the fear that making the Old and New Testaments available in the vernacular would lead to independent interpretations and the erosion of Catholic teaching. "The Supplication of Souls" (1529) brought him into conflict with Tyndale's ally Simon Fish and dissident priest John Frith. Filled with scorn and mounting hatred, these works show that More was not above using base propaganda methods to uphold the Church. Thus in 1527, when Henry embarked on his "great matter" - his determination to annul his union with Catharine of Aragon, which had failed to produce a male heir, and marry Anne Boleyn - he and More were set on a collision course. Wolsey's failure to procure the annulment from the Holy See resulted in his dismissal on October 17, 1529, and, on October 26, More was named new Lord Chancellor. The choice was surprising since More had told Henry he believed in Catherine's legitimacy as queen; perhaps it was felt that as a loyal servant, he would eventually change his mind. He accepted the appointment primarily because he hoped to enact tougher laws against the spread of Lutheranism, unaware that the king's fury at the Pope for standing in his way would open the floodgates of the English Reformation. Along with the outspoken Bishop of Rochester, John Fisher, More became the most visible leader of the English Catholic opposition. During his chancellorship, six Protestants were burned at the stake as heretics, and dozens more were arrested, some dying in prison; the fugitive Frith was seized on a warrant issued by More and put to death in 1533. In "The Apology of Sir Thomas More" (1533), he defended himself by stating he was duty-bound to enforce England's civil laws, including the use of capital punishment against religious dissidents, and emphatically denied rumors he tortured suspects under interrogation. Not only was More swimming against the tide, but his downfall had begun within weeks of his taking office. The first session of the Reformation Parliament (November 1529 to April 1536) initiated Henry's break from Rome. In 1530, More refused to sign a petition to have Pope Clement VII annul Henry's marriage, and the following year, he asked to step down rather than take an oath declaring the king supreme head of the English Church with the proviso "as far as the law of Christ allows." His request was denied. A formidable new enemy, the Reformist Thomas Cromwell, gained entry to the royal inner circle and began whittling away at the power of the bishops (and More) through Parliamentary bills, including limiting the persecution of Protestants. On May 15, 1532, the clergy yielded to Henry's demand that all religious law in England required royal consent. More resigned as Lord Chancellor the next day, citing a heart condition, unable to tolerate further incursions into Catholic authority. Aware that his position was now dangerous, he prepared himself and his family for the likelihood of his arrest. His first act on leaving office was to erect his intended tomb at Chelsea Old Church, its epitaph proudly noting that he was "troublesome to thieves, murderers, and heretics." He did not actively seek martyrdom. He hoped to avoid the royal displeasure by keeping silent about Henry's 1533 annulment from Catherine and marriage to Anne, both performed in defiance of Rome by the accommodating new Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer and for which Henry and Cranmer were excommunicated. More's conspicuous absence at Anne's coronation was noted - he was too high-profile for so much as passive resistance to go unchecked. Cromwell hounded him with investigations, and in February 1534, he was included in a bill of attainder for alleged complicity with the "Nun of Kent" Elizabeth Barton, who had predicted Henry's death and damnation for rejecting the papacy. More admitted interviewing Barton, then managed to escape the charges by producing a letter in which he warned her to keep out of state affairs. On March 23, 1534, Parliament passed the Act of Succession, which established the line of succession through the children of Queen Anne. It also required English subjects to take an oath vowing to uphold the Act and recognize the king's supremacy over "all foreign princes and potentates" (including the pope). Failure to do so when commanded was considered high treason. On April 13, More was summoned to Lambeth Palace to pledge his allegiance to the Act. After reading the texts, he told the commission that while he accepted the right to declare Anne queen, he would not swear to the oath nor explain his refusal. He was remanded to the custody of the Abbot of Westminster and, on April 17, was transported to the Tower of London, where Bishop John Fisher was already being held for taking the same stand. During his 15 months in prison, he wrote his finest religious work, "A Dialogue of Comfort Against Tribulation" (1534), as well as letters to Margaret attempting to explain himself without incriminating either of them; she alone of his loved ones sympathized with his actions. That same period saw the passage of two laws that would lead directly to More's execution: the Act of Supremacy, which formally established Henry as head of the English Church, and the Treason Act, a blanket law that made mere criticism of the king's policies punishable by death. The latter was clearly intended to deal with men like More who posed obstacles to the Reformation. Cromwell visited him several times, demanding to know his thoughts on these acts and promising leniency if he cooperated. More continued to stonewall, saying he had given up "meddling" in worldly affairs and only wanted to lead a good Christian life. On June 22, 1535, John Fisher was executed. Days earlier, the bishop had been found in possession of smuggled letters from More, and Solicitor General Richard Rich was sent to confiscate More's books and writing materials. On that occasion, he and Rich had a seemingly casual discussion that would be manipulated into the principal charge against him. More was tried for treason at Westminster Hall on July 1, 1535. He had no chance of winning acquittal: the panel of judges included Anne Boleyn's father, brother, and uncle, and was led by new Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley, who would keep his head through utter subservience to Henry's will. The jury faced possible reprisals if they sided with the defendant. Nevertheless, he conducted a brilliant defense, the culmination of 40 years' worth of legal experience and study. Visibly frail and wearing a long gray beard, More remained seated throughout, but answered the charges in a firm voice. He had indeed, "according to the dictates of my conscience," expressed opposition to Henry's annulment and remarriage - as a private opinion the king had specifically asked for, which did not constitute treason. To lie under the circumstances would have been a greater sin to both God and sovereign, he maintained. On his failure to swear the oath recognizing the king as leader of the English Church, the judges asserted that More's refusal to divulge his motives was proof of malicious intent. "No law in the world can punish any man for his silence," More countered, citing benefit of the doubt through the legal maxim "qui tacet consentire videtur" ("who is silent is seen to consent"). The third count alleged that in his prison correspondence with Fisher, More tried to persuade the bishop to violate the Treason Act. The letters could not be entered as evidence (it was claimed Fisher had burned them), enabling More to refute the charge as false hearsay. The court then called Richard Rich, who testified that, during their conversation in the Tower, More had, in fact, denied Henry as head of the church. Rich had previously sealed Fisher's doom by persuading him, under false pretenses, to give his honest opinion on the Act of Supremacy, but it is unlikely More would have fallen into the same trap. The accused told the panel he shared his thoughts on the matter with no one and would certainly not have done so with Rich, whom he described as having a reputation for low moral character. If the Solicitor General's account was true, he added, "then I pray I may never see God's face." The two men who accompanied Rich to the Tower were called to corroborate his testimony, but both insisted they were too busy removing More's possessions to hear what was being said. With that, the case was handed over to the jury. They returned with a guilty verdict in 15 minutes. Before sentence was passed More reminded the court that he was entitled to a final "arrest of judgement" statement, and with nothing left to lose he spoke his mind at last, challenging the legality of the proceedings. He stated that his indictment was grounded on a law "directly oppugnant to God." No "temporal prince" could usurp religious leadership from the See of Rome, and Parliament had no right to enact legislation that conflicted with the laws of "Christ's universal Catholic Church." He also explained how provisions in the Succession and Treason Acts negated centuries of English legal precedent, including the Magna Carta. When Audley asked how he alone could defy what "the best learned of this realm" had agreed to support, More replied tha,t outside of England, the view would be the opposite. "I am not bound, my lord, to conform my conscience to the council of one realm against the General Council of Christendom." He concluded, "I shall pray heartily that though your lordships have now here on Earth been judges of my condemnation, we may yet hereafter in heaven merrily all meet together to everlasting salvation." More was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered at Tyburn, the punishment for commoners convicted of treason. Henry commuted the sentence to beheading, supposedly in gratitude for his years of loyal service; he also commanded that the prisoner "not use many words" on the scaffold. The execution took place at London's Tower Hill on July 6, 1535. Before the axe fell, More implored the spectators to bear witness that he died "the king's good servant, and God's first." His body was unceremoniously buried beneath the floor of the nearby Chapel of Saint Peter ad Vincula, to rest with other victims of Henry's wrath (soon to include Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell). More's head was displayed on a pike above London Bridge for a month before his daughter, Margaret Roper, clandestinely rescued it from being tossed into the Thames. When she died in 1544, the skull was buried with her at Chelsea Old Church, in the tomb More had wished to occupy. The remains of both were later reinterred in the Roper Vault at St. Dunstan's Church in Canterbury. News of More's death shocked Continental Europe, where he was regarded as a foremost intellectual. Charles V told the English ambassador, "If I had been master of such a servant...I would rather have lost the best city in my dominions than lose such a worthy councilor." His reputation remained high in England over the backlash of the evangelicals he fought against; even his enemies did not appear to believe he was a traitor, tacitly acknowledging that his execution was an act of judicial murder. Protestant polemicist John Foxe demonized him as "a bitter persecutor of good men" in his "Book of Martyrs" (1563), but granted that, in matters outside of religion, he was "in degree worshipful, in place superior, in wit and learning singular...a man with many worthy ornaments beautified." Anglican author Jonathan Swift called More "a person of the greatest virtue this kingdom ever produced" for sacrificing his life for his beliefs. More and Fisher were beatified by Pope Leo XIII in 1886, and, in 1935, they were canonized by Pope Pius XI, with their feast day on June 22., the anniversary of St. John Fisher's death. In 1980, the Church of England recognized More as a "Reformation martyr" and included him in its Calendar of Saints (July 6). A 1999 poll from the Law Society of Great Britain voted him "Lawyer of the Millenium" over Abraham Lincoln, Mohandas Gandhi, and Nelson Mandela. Having already been named patron saint of attorneys, More was declared "the heavenly patron of statesmen and politicians" by Pope John Paul II in 2000. He was depicted as the idealized hero of conscience in Robert Bolt's 1960 play "A Man for All Seasons" (and its 1966 film adaptation). More was certainly a complex, contradictory man. The same can be said for his masterpiece "Utopia," a work that spawned two literary genres and has influenced political and philosophical thought for centuries. In this imaginative quest for the best possible form of government, More coined the term "Utopia" by combining two Greek words that together mean "no place." His models were Plato's "Republic" (c. 380 BC) and the New World adventures chronicled in "The Four Voyages of Amerigo Vespucci" (published in 1507). The setting is Antwerp during More's 1515 stay in the Low Countries, and the author is a main character. In Book I, he meets veteran traveler Raphael Hythloday, whose exploits include sailing with Vespucci on his last voyage. Hythloday's surname translates as "dealer in nonsense," but he impresses More with his insightful criticisms of the many ills and injustices of European society, England in particular. When More urges him to use his knowledge to benefit mankind by serving as advisor to a monarch, he claims he lacks diplomatic skills and that royal courts are too corrupt to listen to him anyway. He then mentions that he has discovered the ideal commonwealth on a remote island in the Western Hemisphere, and, in Book II, he describes it in great detail. The nation of Utopia is an intricate form of democracy consisting of 54 cities, each ruled by an elected official called a Prince; this is a lifetime position, but the leader can be voted out of office for abuse of power. Money and private property are unknown, as all material needs are supplied for free by the state. It has six-hour workdays, universal healthcare and education, and almost complete religious freedom (atheists are rather grudgingly tolerated). Utopians view war as immoral and hire mercenaries to do their necessary fighting for them. Citizens are required to spend two years working on communal farms for a fair share of agricultural labor; after that they are given employment best suited to their abilities. Engaged couples are allowed to see each other naked to get a better idea of who they are going to spend the rest of their lives with, and consensual divorce for incompatibility is permitted. Euthanasia is a legal option. There are no locked doors, no poverty or hunger, no violent crime. Most tantalizing of all, there are no lawyers, the laws being few and simple enough for the layman to understand. But Utopia is not as ideal as Hythloday insists we believe. It is a severely-regimented society with little privacy or individual freedom. Everyone wears the same clothes, eats the same food, and lives in identical housing. Families are periodically reassigned living quarters to prevent them from gaining roots in one place, or are relocated to other parts of the island to keep the populations of its cities as equal as possible. The few opportunities for personal choice, such as dining at home instead of at a communal hall, are socially frowned upon. There are no taverns or "secret meeting places" to indulge bad habits or ideas, and while the people have much more leisure time, the place seems dreadfully dull. Hythloday rationalizes such enforced conformity because, in Utopia, the negative impulses of human nature are controlled for the common good; he claims the Utopians are contented. In the end, More is skeptical. He admits he would like to see certain elements of Utopia implemented in England but doubts it will ever happen. The insoluble enigma of "Utopia" is More's own viewpoint. Did he intend it to be a serious political manifesto? A satire? A cunning plea for a Catholic theocracy? Nothing in the book can be taken at face value, but the concept of Utopia was so convincingly presented that attempts to reproduce it in life and art began during More's lifetime. The first communities based on utopian principles were founded in Mexico (then part of New Spain) in the early 1530s by Catholic bishop and jurist Vasco de Quiroga, as a means of converting the indigenous population to Christianity and a Spanish way of life. More's book also influenced pioneer socialists Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and Robert Owen, whose theories led to the founding of several short-lived utopian villages in the American Midwest during the mid-1800s. Such experiments were rejected as impractical by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in "The Communist Manifesto" (1848), in which they introduced the term "Utopian socialism" to distinguish lofty speculation on socialist ideals from their own "scientific socialism," which advocated revolutionary action. The 20th Century Israeli kibbutz successfully originated in the utopian organization. In the world of letters, the book's progress was steadier. It was translated into German (1524), Italian (1548), French (1550), English (by Ralph Robinson, 1551), Dutch (1553), and Spanish (1637), while the word "utopia" itself entered standard usage in those languages. In 1532, the French satirist Rabelais referred to the Utopians in the first volume of his "Gargantua and Pantagrue, l" and, in the 17th century, writers began to foster utopian literature by creating their own fictional commonwealths. Notable among these are Tommaso Campanella's "The City of the Sun" (1623), Francis Bacon's "The New Atlantis" (1624), Edward Bellamy's "Looking Backward" (1888), and William Morris' "News from Nowhere" (1891). Swift's classic "Gulliver's Travels" (1726) presents a series of satirical Utopias. H. G. Wells explored the theme in several books, among them "The Time Machine" (1895), "A Modern Utopia" (1905), and "The Shape of Things to Come" (1933). In 1868, John Stuart Mill invented the term "dystopia" ("bad place") to describe nightmare visions of the future, though as a genre it did not become prevalent until the 20th century, spurred by two World Wars and the rise of Communism. Key examples of dystopian fiction include Yevgeny Zamyatin's "We" (1924), Aldous Huxley's "Brave New World" (1932), George Orwell's "1984" (1949), Ray Bradbury's "Fahrenheit 451" (1953), Anthony Burgess' "A Clockwork Orange" (1962), Ursula K. Le Guin's "The Lathe of Heaven" (1971), and Margaret Atwood's "The Handmaid's Tale" (1985). Many works of science fiction in different media employ utopian or dystopian forms.

View body burial: Burial Location with family links.

View head burial: Head Here.

Bio by: Bobb Edwards

Gravesite Details

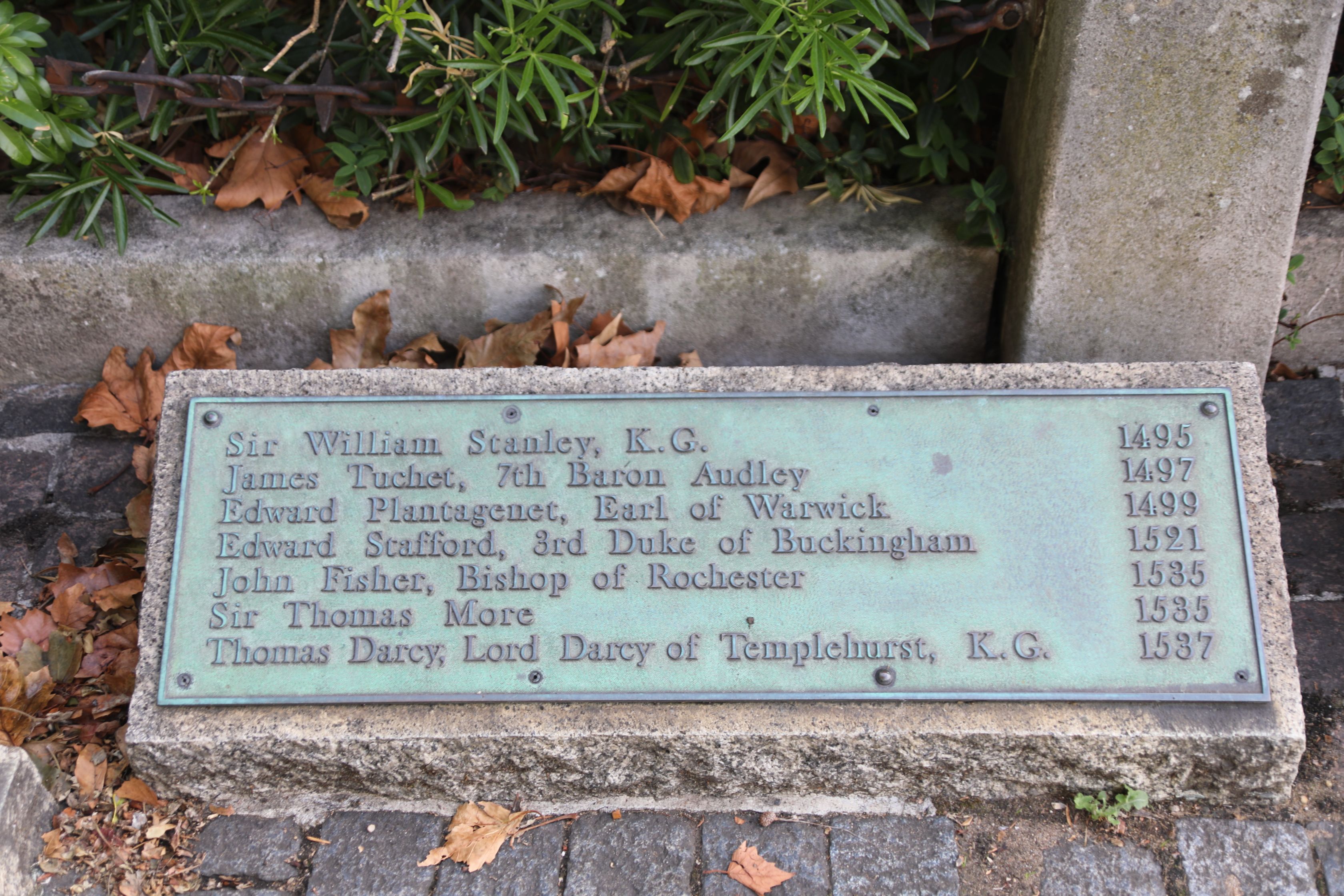

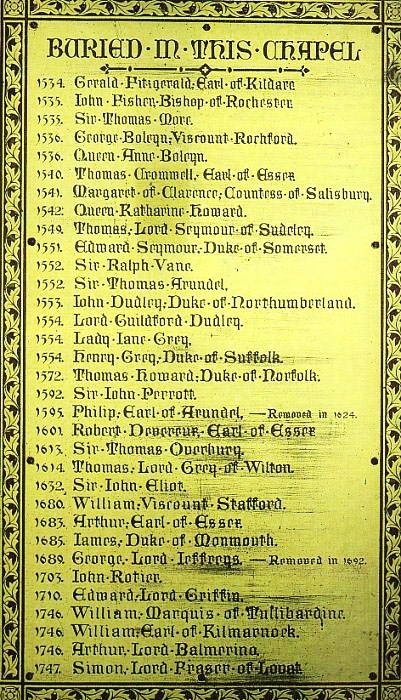

His body, minus his head, was buried in an unmarked mass grave beneath the Royal Chapel of St. Peter Ad Vincula. St Dunstan's Church possesses More's head.

Family Members

Advertisement

See more More memorials in:

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement