City engineer Briggs and party, while engaged in the survey for the waterworks plant extensions west of the reservoir and about one mile southeast of the city, discovered an isolated grave, while nearby a marble headstone was found upon which was inscribed the following:

"Lodowick C. Fitch, born in West Bloomingdale, New York, January 2, 1864"

Inquiry among the Lewiston pioneers developed the information that the deceased was an early resident of Lewiston, being engaged in the mercantile business with a partner, the firm name being Fitch & Bacon. The unfortunate man committed suicide and he was buried where his grave is now located at his own request.

Lewiston Tribune February 11, 1903, pg. 2

=====

A Suspicious Case of Self-Deliverance

Any truth is better than indefinite doubt.

—Arthur Conan Doyle, The Adventure of the Yellow Face

Almost any story is some kind of lie.

—Orson Wells

In early February 1903, city engineer Edson Briggs and his team of surveyors discovered a relic of old Lewiston on a hillside while working on an extension of Lewiston’s waterworks reservoir, about a mile southeast of town. The object was a marble slab with an inscription:

Lodowick C. Fitch

Born in West Bloomingdale, New York

January 2, 1827

Died at Lewiston, I.T.

January 27, 1864

Few Lewiston old-timers had any memories of a local businessman whose body was buried so long before. Those recollections were badly worn with the years, as the headstone itself would attest.

Lodowick Champlin Fitch Jr., or “L.C.” to his associates, was the scion of a wealthy and well-established West Bloomfield, New York merchant family. His father, Lodowick Sr., was “extensively known in the western part of this state for his rare business and social qualities.” Born in February 1788, he served as an original director of the Ontario and Livingstone Mutual Insurance Company, was a leading figure of the Whig Party in New York and worked as a local attorney. He married Sarah Dean on September 17, 1822. Sarah also brought an impressive pedigree to the marriage, as she was the daughter of Stewart Dean, captain of the armed sloop Beaver in the Revolutionary War.

The Fitches raised nine children in their West Bloomfield home—sons Stewart, Lodowick Jr. and Elisha, along with their six daughters. By 1850, all but two of the children had left home. Elisha went to sea and quickly rose to be the master of various United States mail steamers, notably the Washington. Lodowick Sr. died on April 20, 1854. Elisha had much on his mind when he left New York for Southampton, England, a few days later.

On May 2, he came across the packet ship Winchester, which had been de-masted in a major gale, causing the ship to go adrift with 482 passengers and crew aboard. Maneuvering the Washington as close as he dared, Elisha dispatched his first officer and four volunteers to board the Winchester. Their boat began to sink as they reached the ship, but the rescue team was “snatched from a watery grave,” as the Sabbath Recorder reported.

Elisha directed lifeboats into position, and the last survivors left the ship only minutes before it sank from sight. Several persons had died in the storm, and the crew had laid them out on the rolling deck. Remaining to be the last persons off the wreck, Washington’s first officer P.W. King and the captain of the Winchester made one final survey of the dead and found a woman who was still breathing. For their heroism, Elisha and his crew were awarded medals and large monetary rewards and were repeatedly feted in New York City.

Elisha went on the command the steamship Sonora, carrying passengers from New York to Bremen, Germany, and died at sea aboard the ship on July 22, 1858, leaving his wife, Louisa, with four children in Brooklyn. However, where was Lodowick Jr. in this story?

His name appears for the first time in the March 22, 1854, edition of the Sacramento (California) Daily Union. He had left Panama earlier that month aboard the SS California, bound for San Francisco, which he reached on March 21, a month before his father’s death. It would be many more months before he would hear the news of his father’s burial and years before he would read of the drama aboard the Winchester.

His life in California is a patchwork of isolated facts. At least one unconfirmed source reports that he married in 1855. What we know of his work comes from the 1861 edition of the Langley San Francisco City Directory, in which he is listed as the agent for the McCarthy Automatic Steam Boiler Safety Valve. He arrived back in New York aboard the steamship North Star from Aspinwall, Panama, in May 1860, to negotiate his contract with McCarthy. Business took him to Louisiana in December, where he is found checking into the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans on the thirteenth. His stay in the East lasted until February 1861, when he finally embarked for his return to San Francisco via Panama. The April 8 issue of the Daily Alta California reported on the recent return of “Mr. S. Fitch” and included an extensive description of the safety valve. The man in question was Samuel S. Fitch. A new market for the steam valve seemed ready at hand, and Lodowick wasted no time demonstrating the new technology. Then, the lure of Idaho then began to call our enterprising thirty-five-year-old. 033

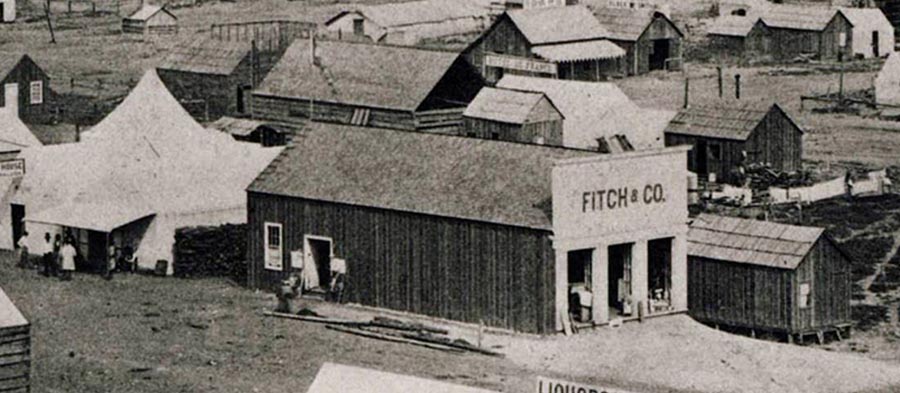

By August 1862, the firm of Fitch & Company, dry goods and general merchandise business, was a fixture on the corner of Third and D Streets in Lewiston, where the city’s community development offices are now located. Based on the best evidence, at some point in 1863, Fitch took on a junior partner, Levin Bacon, a young man with an obvious future. Bacon was the only Democratic member of the First Idaho Territorial Legislature that convened in Lewiston on December 7, 1863. He was soon swept up in the events surrounding the brutal murders of Lloyd Magruder and his companions in October of that year. 034

In August 1940, William Bacon, Levin’s son, visited Lewiston. He related to a reporter that his father was the hangman at the March 4, 1864, execution of the killers (Historic Firsts 47–48). His father spoke often of the events that transpired at the foot of Poe Grade (Thirteenth Street) that fateful Friday morning. Levin was an acquaintance of one of the convicted men and felt bad about the role he was about to play in his death. However, the condemned criminal turned to him and said, “Go ahead. Somebody has to do it.”

Lewiston must have been a dismal place in 1864. The census that year listed only 225 inhabitants, many of them newly arrived Chinese. The town’s very existence seemed threatened by its dwindling numbers and by reports of a possible withdrawal of federal troops from nearby Fort Lapwai. On March 1, Fitch wrote to Brigadier General Benjamin Alvord, commander of the U.S. Volunteers in the Oregon District. In his letter, Fitch told Alvord, “So far as I can judge the public verdict of the people is that the establishment of Fort Lapwai prevented an Indian war.” In his reply on March 14, Alvord assured him that any rumors of an abandonment of the fort were unfounded and included a compliment: “It gratifies me to hear such language from an intelligent source, as my efforts for the defense of Idaho Territory have been underrated in some quarters.” The fort was going to stay. Fitch had a lot invested in Lewiston.

On April 4, 1864, Nez Perce County held its first regularly scheduled election to fill public offices. Bacon won the position as the first elected Nez Perce County assessor in the balloting that secured the office of county superintendent of schools for Lodowick Fitch. The next mention of Fitch appears in the October 15, 1864 edition of the Daily Union. And the news was not good.

SUICIDE.—We learn from the Golden Age, of Lewiston (I.T.), that L.C. Fitch, a respectable hardware merchant of that city, committed suicide on Thursday, September 22d, by shooting himself with a revolver, the ball entering the right side of the head, near the ear, coming out of the left side, just above the temple. The deceased was conducting a lucrative business, of perfectly sane mind, enjoying the confidence and respect of the community.

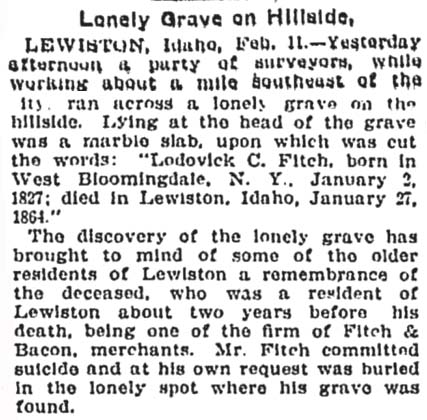

When Briggs and his staff located the grave and headstone more than thirty-eight years later, the Fitch name meant nothing to them. The surveyors were not surprised by the discovery, as several isolated grave sites have been found in or near the city. A reporter for the Lewiston Morning Tribune queried “some of the older residents of Lewiston,” who stated that Fitch had committed suicide and “at his request was buried in the lonely spot where his grave was found.”

Those are the facts accepted at the time. However, let us explore Lodowick’s death using the methods employed by modern law enforcement investigators in cases of suicide and attempt to answer whether Fitch took his own life or someone murdered him?

In his work Practical Homicide Investigation: Tactics, Procedures, and Forensic Techniques, Vernon Geberth, a forty-year veteran of the Bronx Police Department and commander of their homicide task force, outlines three basic considerations to establish that a death is really a suicide:

1. The presence of the weapon or means of death at the scene

2. Injuries or wounds that are obviously self-inflicted, or could have been inflicted by the deceased

3. The existence of a motive or intent on the part of the victim to take his or her own life

All right all you CSI fans, what conclusions can we reach based on the scanty evidence?

First, the report from the Golden Age states that a revolver delivered the fatal wound. If the revolver was still at the scene, a reasonable person would ask, “Was it his revolver?” Did those who found his body just assume that a revolver was used?

Second, while it is true that the wound described in the Golden Age could have been inflicted by Fitch, whoever reported finding the body would not likely have had the skills necessary to distinguish the beveling of the bones of the skull found at entry and exit points. Fired at the angle described in the news report, the bullet would have produced very similar damage to his head. Was Fitch right-handed? If he had been shot at very close range, any revolver of that period would have deposited considerable stippling, the soot residue left by a gunshot at close range and not blocked by clothing. No one mentioned powder burns.

You are probably asking where was the county coroner? The first documented election of a Nez Perce County coroner took place in November 1872, when Walter Dyer won the office. Dyer had come to the county in 1862 and was a longtime member of the farming department at the Nez Perce Reservation. Thus, we are left with unqualified people making unqualified claims.

Before continuing to a discussion of motive, the location of Fitch’s body, the timing of the report and the headstone raise some troubling questions. His grave was found near what is now Twenty-sixth Street in Lewiston. At the time, the site was about two miles from the center of town, too far for the direction of a gunshot to be determined, and few people were startled to hear gunshots in Lewiston in September 1864. As no road ran near the site, an innocent passerby would have come across his body only by accident. If Fitch did leave a note, he would have had no idea how long it would be before someone found his remains.

The headstone certainly raises questions, as the inscription contains glaring discrepancies. The headstone gives his hometown as West Bloomingdale, New York, with a birth date of January 2. Fitch was born on January 3 in West Bloomfield. Well, it is at least close. Most surprising, however, is the difference in the day of death. The stone reads January 27, when the reported date was September 22. Unless Fitch ordered his own stone and then delayed his suicide, someone with a faulty memory had the marker carved at a much later date. We do know at least one thing about the stone: it was carved before July 1, 1890, when Idaho gained statehood. Fitch’s grave remained untended and undocumented for nearly four decades.

So then, what would have been Fitch’s motive to kill himself? The Golden Age report stated that he enjoyed “the confidence and respect of the community.” He was entrusted with the management of the school system, and Lewiston has always taken its schools and those who lead them very seriously.

Financial insecurities do not prove to be a reasonable answer. His hardware company was “a lucrative business.” Indeed, business registries and newspapers continued to mention “Fitch & Co” at its Third and D Streets location as late as 1866. The same old-timers who remembered Fitch did so as a partner of “Fitch & Bacon,” a name that does not appear in any primary sources and would lead us to believe that Bacon assumed ownership after Lodowick’s death. Yes, I know. I too am asking who would have benefited from his death.

One might speculate that depression may have been a factor. Research has demonstrated that four out of five men who kill themselves (usually by gunshot) resort to self-deliverance as a result of depression. In Men and Depression, James Ellison notes some important issues:

Women who are depressed often cry and talk about the sadness, low energy and loss of fun. A depressed man may not want anyone to see him as weak or out of control. His depression takes a different form. He may show a bad temper or even anger instead of sadness. He might have trouble working. He might blame a physical problem such as arthritis for pain that is more than you would expect with that disease. He might get into alcohol or drugs, or unsafe behavior. Men are less likely to ask for help.

If Lodowick Fitch suffered from depression, no one recognized it or probably would have. He was, to everyone, a man “of perfectly sane mind.” No one saw any loss of interest in his work or an inability to concentrate on the details and responsibilities of his business—both of which are key signs and symptoms of depression in men. Marital strife can also be discounted. A thorough search of the California marriage records and New York genealogical charts fail to show any union, and the report of his death makes no reference to a widow.

We finally come to a crucial piece of evidence: the “suicide note,” which would be an indication of intent. Fitch had supposedly left instructions to bury him where he was found. Such a note would suggest suicide. However, the idea of a note of burial instructions arose only in 1903, and death notes are left in less than twenty-five percent of all cases. Let’s assume for a moment that a note was found. Today, investigators are schooled to treat suicide notes like any other piece of crime scene evidence. They will study many features: handwriting, the angle on the page, the slant of the letters and the spacing of the words. More importantly, an exemplary, or sample, of the victim’s handwriting will be compared to the note. That most certainly did not happen in September 1864.

Whoever found his body took the note at face value. As that scrap of paper was long ago discarded, we cannot compare it with the characteristics of the genuine and the fake. A murderer could have penned the note or had Fitch write it before killing him. One has to wonder why Fitch left no instructions describing how his company was to be managed. “Bury me here” leaves a lot to the imagination.

Levin Bacon continued to live in Lewiston after Fitch’s death. If anyone suspected him, they were not talking. It was not the first or last time that a felon would live undisturbed in Lewiston. He hired on as a driver for Felix Warren by 1869. In 1871, he and two friends won a parcel of land on Tenth Street in a poker game and subsequently quitclaimed it as the site for a new public school. On June 15, 1876, we find him in St. George, Utah, where he married eighteen-year-old Cecelia White, an English immigrant twenty years his junior. The Bacons moved to Dry Canyon, Utah, and started a family, which included two sons and a daughter. On January 26, 1892, Levin suffered disfiguring injuries to his face, hands, and body when a spark from his candle ignited a box of blasting caps. He did not fully recover and died in June 1896. 035

Benjamin Alvord would have more to say about Lewiston five months after Lodowick’s death. Governor Caleb Lyon had fled the territory and an arrest warrant after the second territorial legislature voted to move the capital to Boise City. A local judge placed his interim secretary under house arrest and locked the territorial seal and essential government documents in the prison. President Lincoln’s patience with the chaos ran out, and he ordered Alvord to settle the matter, which he did, directing a detachment of the First Oregon Volunteer Cavalry from Lapwai to accompany Clinton DeWitt Smith, the new secretary, to seize the emblems of office. The deed was done on March 30, 1865, and north Idaho residents have never stopped talking about it.

The discovery of the Fitch’s grave site [All of my sources list this as one word, and it appears as such in Lost Lewiston.] in 1903 moved his sisters, Annie and Mary, to have his remains exhumed and transported, along with the headstone, to Pontiac, Michigan, where the sisters lived for decades. Lodowick’s mother, Sarah, had remarried and then died there in October 1878, knowing her son was dead without being able to find his grave. 036

Fitch was reburied in Oak Hill Cemetery, his inscription being added to Sarah’s monument. The timing of this familial and final act of love is confirmed by a simple fact: Lewiston is referred to as being in Idaho, not the Idaho Territory. A Michigan engraver would have had no reason to etch “Idaho Territory” into the granite monolith in 1903.

Winston Churchill once described the Soviet Union as “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” The death of Lodowick Champlin Fitch Jr. is no less a conundrum.

Wicked Lewiston: A Sinful Century

By Steven Branting

============================================

Son of:

Sarah Stewart Dean Fitch

Birth 2 June 1794 in Albany, Albany, NY, USA

Death 4 October 1878 in Pontiac, Oakland, MI, USA

and

Lodowick Champlin Fitch, Sr.

Birth 9 February 1788 in Lyme, New London, CT, USA

Death April 20, 1854 in West Bloomfield, Ontario, NY, USA

=====

City engineer Briggs and party, while engaged in the survey for the waterworks plant extensions west of the reservoir and about one mile southeast of the city, discovered an isolated grave, while nearby a marble headstone was found upon which was inscribed the following:

"Lodowick C. Fitch, born in West Bloomingdale, New York, January 2, 1864"

Inquiry among the Lewiston pioneers developed the information that the deceased was an early resident of Lewiston, being engaged in the mercantile business with a partner, the firm name being Fitch & Bacon. The unfortunate man committed suicide and he was buried where his grave is now located at his own request.

Lewiston Tribune February 11, 1903, pg. 2

=====

A Suspicious Case of Self-Deliverance

Any truth is better than indefinite doubt.

—Arthur Conan Doyle, The Adventure of the Yellow Face

Almost any story is some kind of lie.

—Orson Wells

In early February 1903, city engineer Edson Briggs and his team of surveyors discovered a relic of old Lewiston on a hillside while working on an extension of Lewiston’s waterworks reservoir, about a mile southeast of town. The object was a marble slab with an inscription:

Lodowick C. Fitch

Born in West Bloomingdale, New York

January 2, 1827

Died at Lewiston, I.T.

January 27, 1864

Few Lewiston old-timers had any memories of a local businessman whose body was buried so long before. Those recollections were badly worn with the years, as the headstone itself would attest.

Lodowick Champlin Fitch Jr., or “L.C.” to his associates, was the scion of a wealthy and well-established West Bloomfield, New York merchant family. His father, Lodowick Sr., was “extensively known in the western part of this state for his rare business and social qualities.” Born in February 1788, he served as an original director of the Ontario and Livingstone Mutual Insurance Company, was a leading figure of the Whig Party in New York and worked as a local attorney. He married Sarah Dean on September 17, 1822. Sarah also brought an impressive pedigree to the marriage, as she was the daughter of Stewart Dean, captain of the armed sloop Beaver in the Revolutionary War.

The Fitches raised nine children in their West Bloomfield home—sons Stewart, Lodowick Jr. and Elisha, along with their six daughters. By 1850, all but two of the children had left home. Elisha went to sea and quickly rose to be the master of various United States mail steamers, notably the Washington. Lodowick Sr. died on April 20, 1854. Elisha had much on his mind when he left New York for Southampton, England, a few days later.

On May 2, he came across the packet ship Winchester, which had been de-masted in a major gale, causing the ship to go adrift with 482 passengers and crew aboard. Maneuvering the Washington as close as he dared, Elisha dispatched his first officer and four volunteers to board the Winchester. Their boat began to sink as they reached the ship, but the rescue team was “snatched from a watery grave,” as the Sabbath Recorder reported.

Elisha directed lifeboats into position, and the last survivors left the ship only minutes before it sank from sight. Several persons had died in the storm, and the crew had laid them out on the rolling deck. Remaining to be the last persons off the wreck, Washington’s first officer P.W. King and the captain of the Winchester made one final survey of the dead and found a woman who was still breathing. For their heroism, Elisha and his crew were awarded medals and large monetary rewards and were repeatedly feted in New York City.

Elisha went on the command the steamship Sonora, carrying passengers from New York to Bremen, Germany, and died at sea aboard the ship on July 22, 1858, leaving his wife, Louisa, with four children in Brooklyn. However, where was Lodowick Jr. in this story?

His name appears for the first time in the March 22, 1854, edition of the Sacramento (California) Daily Union. He had left Panama earlier that month aboard the SS California, bound for San Francisco, which he reached on March 21, a month before his father’s death. It would be many more months before he would hear the news of his father’s burial and years before he would read of the drama aboard the Winchester.

His life in California is a patchwork of isolated facts. At least one unconfirmed source reports that he married in 1855. What we know of his work comes from the 1861 edition of the Langley San Francisco City Directory, in which he is listed as the agent for the McCarthy Automatic Steam Boiler Safety Valve. He arrived back in New York aboard the steamship North Star from Aspinwall, Panama, in May 1860, to negotiate his contract with McCarthy. Business took him to Louisiana in December, where he is found checking into the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans on the thirteenth. His stay in the East lasted until February 1861, when he finally embarked for his return to San Francisco via Panama. The April 8 issue of the Daily Alta California reported on the recent return of “Mr. S. Fitch” and included an extensive description of the safety valve. The man in question was Samuel S. Fitch. A new market for the steam valve seemed ready at hand, and Lodowick wasted no time demonstrating the new technology. Then, the lure of Idaho then began to call our enterprising thirty-five-year-old. 033

By August 1862, the firm of Fitch & Company, dry goods and general merchandise business, was a fixture on the corner of Third and D Streets in Lewiston, where the city’s community development offices are now located. Based on the best evidence, at some point in 1863, Fitch took on a junior partner, Levin Bacon, a young man with an obvious future. Bacon was the only Democratic member of the First Idaho Territorial Legislature that convened in Lewiston on December 7, 1863. He was soon swept up in the events surrounding the brutal murders of Lloyd Magruder and his companions in October of that year. 034

In August 1940, William Bacon, Levin’s son, visited Lewiston. He related to a reporter that his father was the hangman at the March 4, 1864, execution of the killers (Historic Firsts 47–48). His father spoke often of the events that transpired at the foot of Poe Grade (Thirteenth Street) that fateful Friday morning. Levin was an acquaintance of one of the convicted men and felt bad about the role he was about to play in his death. However, the condemned criminal turned to him and said, “Go ahead. Somebody has to do it.”

Lewiston must have been a dismal place in 1864. The census that year listed only 225 inhabitants, many of them newly arrived Chinese. The town’s very existence seemed threatened by its dwindling numbers and by reports of a possible withdrawal of federal troops from nearby Fort Lapwai. On March 1, Fitch wrote to Brigadier General Benjamin Alvord, commander of the U.S. Volunteers in the Oregon District. In his letter, Fitch told Alvord, “So far as I can judge the public verdict of the people is that the establishment of Fort Lapwai prevented an Indian war.” In his reply on March 14, Alvord assured him that any rumors of an abandonment of the fort were unfounded and included a compliment: “It gratifies me to hear such language from an intelligent source, as my efforts for the defense of Idaho Territory have been underrated in some quarters.” The fort was going to stay. Fitch had a lot invested in Lewiston.

On April 4, 1864, Nez Perce County held its first regularly scheduled election to fill public offices. Bacon won the position as the first elected Nez Perce County assessor in the balloting that secured the office of county superintendent of schools for Lodowick Fitch. The next mention of Fitch appears in the October 15, 1864 edition of the Daily Union. And the news was not good.

SUICIDE.—We learn from the Golden Age, of Lewiston (I.T.), that L.C. Fitch, a respectable hardware merchant of that city, committed suicide on Thursday, September 22d, by shooting himself with a revolver, the ball entering the right side of the head, near the ear, coming out of the left side, just above the temple. The deceased was conducting a lucrative business, of perfectly sane mind, enjoying the confidence and respect of the community.

When Briggs and his staff located the grave and headstone more than thirty-eight years later, the Fitch name meant nothing to them. The surveyors were not surprised by the discovery, as several isolated grave sites have been found in or near the city. A reporter for the Lewiston Morning Tribune queried “some of the older residents of Lewiston,” who stated that Fitch had committed suicide and “at his request was buried in the lonely spot where his grave was found.”

Those are the facts accepted at the time. However, let us explore Lodowick’s death using the methods employed by modern law enforcement investigators in cases of suicide and attempt to answer whether Fitch took his own life or someone murdered him?

In his work Practical Homicide Investigation: Tactics, Procedures, and Forensic Techniques, Vernon Geberth, a forty-year veteran of the Bronx Police Department and commander of their homicide task force, outlines three basic considerations to establish that a death is really a suicide:

1. The presence of the weapon or means of death at the scene

2. Injuries or wounds that are obviously self-inflicted, or could have been inflicted by the deceased

3. The existence of a motive or intent on the part of the victim to take his or her own life

All right all you CSI fans, what conclusions can we reach based on the scanty evidence?

First, the report from the Golden Age states that a revolver delivered the fatal wound. If the revolver was still at the scene, a reasonable person would ask, “Was it his revolver?” Did those who found his body just assume that a revolver was used?

Second, while it is true that the wound described in the Golden Age could have been inflicted by Fitch, whoever reported finding the body would not likely have had the skills necessary to distinguish the beveling of the bones of the skull found at entry and exit points. Fired at the angle described in the news report, the bullet would have produced very similar damage to his head. Was Fitch right-handed? If he had been shot at very close range, any revolver of that period would have deposited considerable stippling, the soot residue left by a gunshot at close range and not blocked by clothing. No one mentioned powder burns.

You are probably asking where was the county coroner? The first documented election of a Nez Perce County coroner took place in November 1872, when Walter Dyer won the office. Dyer had come to the county in 1862 and was a longtime member of the farming department at the Nez Perce Reservation. Thus, we are left with unqualified people making unqualified claims.

Before continuing to a discussion of motive, the location of Fitch’s body, the timing of the report and the headstone raise some troubling questions. His grave was found near what is now Twenty-sixth Street in Lewiston. At the time, the site was about two miles from the center of town, too far for the direction of a gunshot to be determined, and few people were startled to hear gunshots in Lewiston in September 1864. As no road ran near the site, an innocent passerby would have come across his body only by accident. If Fitch did leave a note, he would have had no idea how long it would be before someone found his remains.

The headstone certainly raises questions, as the inscription contains glaring discrepancies. The headstone gives his hometown as West Bloomingdale, New York, with a birth date of January 2. Fitch was born on January 3 in West Bloomfield. Well, it is at least close. Most surprising, however, is the difference in the day of death. The stone reads January 27, when the reported date was September 22. Unless Fitch ordered his own stone and then delayed his suicide, someone with a faulty memory had the marker carved at a much later date. We do know at least one thing about the stone: it was carved before July 1, 1890, when Idaho gained statehood. Fitch’s grave remained untended and undocumented for nearly four decades.

So then, what would have been Fitch’s motive to kill himself? The Golden Age report stated that he enjoyed “the confidence and respect of the community.” He was entrusted with the management of the school system, and Lewiston has always taken its schools and those who lead them very seriously.

Financial insecurities do not prove to be a reasonable answer. His hardware company was “a lucrative business.” Indeed, business registries and newspapers continued to mention “Fitch & Co” at its Third and D Streets location as late as 1866. The same old-timers who remembered Fitch did so as a partner of “Fitch & Bacon,” a name that does not appear in any primary sources and would lead us to believe that Bacon assumed ownership after Lodowick’s death. Yes, I know. I too am asking who would have benefited from his death.

One might speculate that depression may have been a factor. Research has demonstrated that four out of five men who kill themselves (usually by gunshot) resort to self-deliverance as a result of depression. In Men and Depression, James Ellison notes some important issues:

Women who are depressed often cry and talk about the sadness, low energy and loss of fun. A depressed man may not want anyone to see him as weak or out of control. His depression takes a different form. He may show a bad temper or even anger instead of sadness. He might have trouble working. He might blame a physical problem such as arthritis for pain that is more than you would expect with that disease. He might get into alcohol or drugs, or unsafe behavior. Men are less likely to ask for help.

If Lodowick Fitch suffered from depression, no one recognized it or probably would have. He was, to everyone, a man “of perfectly sane mind.” No one saw any loss of interest in his work or an inability to concentrate on the details and responsibilities of his business—both of which are key signs and symptoms of depression in men. Marital strife can also be discounted. A thorough search of the California marriage records and New York genealogical charts fail to show any union, and the report of his death makes no reference to a widow.

We finally come to a crucial piece of evidence: the “suicide note,” which would be an indication of intent. Fitch had supposedly left instructions to bury him where he was found. Such a note would suggest suicide. However, the idea of a note of burial instructions arose only in 1903, and death notes are left in less than twenty-five percent of all cases. Let’s assume for a moment that a note was found. Today, investigators are schooled to treat suicide notes like any other piece of crime scene evidence. They will study many features: handwriting, the angle on the page, the slant of the letters and the spacing of the words. More importantly, an exemplary, or sample, of the victim’s handwriting will be compared to the note. That most certainly did not happen in September 1864.

Whoever found his body took the note at face value. As that scrap of paper was long ago discarded, we cannot compare it with the characteristics of the genuine and the fake. A murderer could have penned the note or had Fitch write it before killing him. One has to wonder why Fitch left no instructions describing how his company was to be managed. “Bury me here” leaves a lot to the imagination.

Levin Bacon continued to live in Lewiston after Fitch’s death. If anyone suspected him, they were not talking. It was not the first or last time that a felon would live undisturbed in Lewiston. He hired on as a driver for Felix Warren by 1869. In 1871, he and two friends won a parcel of land on Tenth Street in a poker game and subsequently quitclaimed it as the site for a new public school. On June 15, 1876, we find him in St. George, Utah, where he married eighteen-year-old Cecelia White, an English immigrant twenty years his junior. The Bacons moved to Dry Canyon, Utah, and started a family, which included two sons and a daughter. On January 26, 1892, Levin suffered disfiguring injuries to his face, hands, and body when a spark from his candle ignited a box of blasting caps. He did not fully recover and died in June 1896. 035

Benjamin Alvord would have more to say about Lewiston five months after Lodowick’s death. Governor Caleb Lyon had fled the territory and an arrest warrant after the second territorial legislature voted to move the capital to Boise City. A local judge placed his interim secretary under house arrest and locked the territorial seal and essential government documents in the prison. President Lincoln’s patience with the chaos ran out, and he ordered Alvord to settle the matter, which he did, directing a detachment of the First Oregon Volunteer Cavalry from Lapwai to accompany Clinton DeWitt Smith, the new secretary, to seize the emblems of office. The deed was done on March 30, 1865, and north Idaho residents have never stopped talking about it.

The discovery of the Fitch’s grave site [All of my sources list this as one word, and it appears as such in Lost Lewiston.] in 1903 moved his sisters, Annie and Mary, to have his remains exhumed and transported, along with the headstone, to Pontiac, Michigan, where the sisters lived for decades. Lodowick’s mother, Sarah, had remarried and then died there in October 1878, knowing her son was dead without being able to find his grave. 036

Fitch was reburied in Oak Hill Cemetery, his inscription being added to Sarah’s monument. The timing of this familial and final act of love is confirmed by a simple fact: Lewiston is referred to as being in Idaho, not the Idaho Territory. A Michigan engraver would have had no reason to etch “Idaho Territory” into the granite monolith in 1903.

Winston Churchill once described the Soviet Union as “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” The death of Lodowick Champlin Fitch Jr. is no less a conundrum.

Wicked Lewiston: A Sinful Century

By Steven Branting

============================================

Son of:

Sarah Stewart Dean Fitch

Birth 2 June 1794 in Albany, Albany, NY, USA

Death 4 October 1878 in Pontiac, Oakland, MI, USA

and

Lodowick Champlin Fitch, Sr.

Birth 9 February 1788 in Lyme, New London, CT, USA

Death April 20, 1854 in West Bloomfield, Ontario, NY, USA

=====

Gravesite Details

cemetery has no record of him being there, even though his name is on marker. This could be a cenotaph.

Family Members

Advertisement

Advertisement