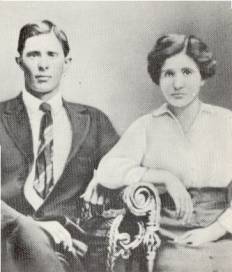

Nannie Bess DOB: August 7, 1897

Married: April 7, 1915

Nannie Bess died: March 25, 1962

Age: 64 years, 7 months, 18 days.

Buried: 27 March 1962.

(Date of death on grave stone says March 25th. Death certificate says March 26th).

Nannie Bess Yarbrough's parents were:

Will J. Yarbrough m. Bettie Bell White on September 13, 1896

Will was born March 4, 1873 and died in 1951

Nannie Bess Yarbrough's Paternal grandparents were:

John Newton Yarbrough (born in 1846) m. Sara Adeline Doster (born January 7, 1850)

Married in 1867

John died on June 11, 1921. Sara died on August 17, 1913

Married to Clarence Melvin Raulston, Jr.

Children: Two infant daughters, Clarence Melvin Raulston, Jr., Katie Raulston (died age 10), Willie Garland Raulston, Herbert Wayne (Hub) Raulston, Kent Raulston, and Cora Sue Raulston Boone.

[Uncle C.M. wrote the following via e-mail to Paula Raulston Duchesne for the purpose of adding to our website.]

"My name is Clarence Melvin Raulston, Jr. I was born October 15, 1920 at Dimple, on the Raulston Homestead, in the house where my father and his father were born. My father was Clarence Melvin Raulston Sr.(1894-1978).

When I was about 14 years old he told me and a couple of other boys the following story.

*******************************************

In the spring of 1914 I was at the church and we had all stood up to sing the first hymn when the door was pushed open and someone entered. As was the custom then, everyone turned to see who had entered. It was the family of William Joseph Yarbrough who was new in the community. Walking beside her mother was the prettiest little gal I had ever seen in my life!

She wasn't more than five feet tall with black hair and sparkling brown eyes that seemed to be looking straight at me. I blushed a little and told myself, " I'm gonna wait for that little gal, she can't be more than fourteen and already ready built like a brick chicken house! After the service I discovered she was almost seventeen and we commenced to sparking right there". Mr. Yarbrough had bought the John C. Raulston place which put the girl next door west of Clarence.

Mr. Yarbrough had a habit which was admired by most but proved to be his ruination. It was his custom to roll out of bed before daybreak and straightaway buiId a fire in the woodburning cookstove, then go to the living room where he lighted the coal-oil lamp and proceeded to study his Bible for about fifteen minutes before rousing up his wife. Being a man of the Fannin County Prairie, Mr. Yarbrough did not know what would happen if one overcharged a cookstove with dry pine wood. His Bible study period was almost over before he became aware of the fire which had already involved the whole south end of the kitchen. They got all the kids out but were able to save very little else. Mr. Yarbrough sold out immediately to Jimmie D. Raulston and loaded his family onto the train bound for Windom in Fannin County. Clarence was mighty blue when that train pulled out with his tearful little sweetheart on board. (That experience, I am sure, was the cause of his comment to me on several occasions as we walked from the barn towards the house on those damp, cold and foggy mornings when the acoustics were such that the train going west from Clarksville sounded like it was no more than a mile away. When those old time engineers blew the whistle at approaching road crossings they had a way of making those old steamwhistles sound like the wail of a swampangel searching for a lost child. Daddv would turn toward the sound and exclaim "LORD ALMIGHTY! I wish they wouldn't do that, there's not a more lonesome sound in this world than the sound of a trainwhistle going away".)

He had a widowed sister with three Young children in addition to two younger brothers living with him which made it impractical for him to get married, but he had an understanding with the young lady that he would travel to her father's home and get permission to marry her just as soon as he possibly could. She promised to wait faithfully until that joyous day arrived. During the winter of 1914-1915, The sister, Mattie Max Raulston Brady, got herself engaged to a widower who had been courting her for almost a year. They would leave for Gallup, New Mexico in the spring. The eldest of the two brothers, Ernest, obtained gainful employment in the County Seat and moved out. On April 6, 1915 Clarence loaded a fattened hog into the wagon and headed for town. He had thirty cents in his pocket when he departed the farm. He sold the hog for $15.00, drove his wagon and team to the mulebarn and hotfooted to the railroad station in time to board the train outbound for Windom. His arrival in Windom was late in the day so he put up for the night with The Fletcher Yarbrough family, an uncle of the bride to be. Next day he rented a buggy and a highstepping black gelding in Windom and drove out to the farm south of town. After he had visited a decent amount of time with the family he loaded his intended and her luggage into the rig and drove to Honey Grove where on April 15, 1915 he married Nannie Bess Yarbrough sitting in the rig on the public square.

Nannie Bess was quite popular in Honey Grove and a small crowd gathered around the buggy to witness the ceremony. They returned to Clarksville by train, picked up the wagon and team at the mulebarn and arrived at the farm after dark. I feel certain Mattie May had a hot meal waiting on the back of the stove. Next day Clarence discovered he had thirty-seven cents in his pocket. He reported to his bride they had made seven cents on the trip.

There are unwritten facts running between the lines in this story. First, modes of transport. In 1915 there were probably fewer than 100 motor vehicles in all of Red River County. Travel from city to village, however short the distance, if the railroad went there, you traveled by train.,, Local travel was on unimproved County Roads by horseback, horse and buggy or wagon and team. It was much slower and uncomfortable but a lot safer and much more tranquil. Didn't have much highway rage then. Second, Economics. People did not buy things which were not pertinent to the task at hand. The lady of the Fletcher Yarbrough house had adequate warning of Clarence's impending arrival to put his name in the pot for the evening meal, which usually involved wringing the neck of another spring chicken. He had a hearty breakfast back at the farm before daybreak. A soda-pop on the train cost ten cents and a cold sandwich came to twenty-five cents. You have to multiply those numbers by twenty to get to 2001 prices.

The youngest of the two younger brothers was Farris (1904-1957) who was a month or so shy of eleven years of age when Nannie Bess became part of the family. The two of them formed a bond which would endure the remainder of their lives. I never heard him refer to her as anything but Sis. Nannie Bess died in 1962 a few months short of age 65. They both died from coronary occlusion.

Mother and Father had two daughters die in infancy then two sons were born. In 1923 Father came down with dengue fever, commonly called "breakbone fever," and was told by his doctor that in order to survive he must change climates. He loaded his wife and two infant sons into a covered wagon and headed West. The wagon was furnished with a full size mattress, a coal bucket, and a minimum of clothing, utensils and tools. They had no specific destination in mind when they left. When they reached a point just west of old Camp Bowie, in what is now the Ridglea Section of Fort Worth, a decision had to be made. Here the road forked, one branch turning south to the Rio Grande Valley, the other pointing straight ahead to the South Plains. After a short conversation they agreed that the road going west looked better and proceeded in that direction. Twenty-seven days after their departure from their farm in Red River County they were in Lubbock, a distance of more than four hundred miles.

These two transplanted East Texans stuck it out for two years in the Lubbock area farming rented or leased land. Many were their trials and tribulations, and deep was their longing for the Piney Woods of home. Mother had to learn simple things such as it takes much longer to cook boiled vegetables at that elevation. Father had to learn to use multi-row implements such as go-devils behind a four-horse hitch. In the late summer of 1924, Clarence M., Sr., was sitting on the fence with his landlord looking across his acreage of lush cotton. They were speculating that the yield would be a bale and one-half to two bales per acre. They were also speculating that the small thunderhead approaching from the southwest might yield a cooling shower. Thirty minutes later, after a brief but very violent hailstorm, there was nothing but stubble left in the cotton fields. Father decided immediately that he would subject himself and family to no more hardships in that strange country.

He sold out lock, stock and barrel and loaded his family on a train whose destination was Red River County. They lived one year in the small town of Bagwell, and in the autumn of 1925 Father moved back to the Raulston home place where he remained until his death.

My Father often commented that it seems his accomplishments in this life have been minimal. My Wife and I have told him that for him and Mother to have reared and educated four sons and a daughter on the proceeds from a small sandy land farm in times of depression are by no means small accomplishments. Their work day started before dawn and ended after dark, and bed time was when the supper dishes were washed, for it had been a hard day and tomorrow would be another.

Wednesday's wash was the special horror of every farm wife. The day started with a fire around the cast iron wash pot filled with water and heavily saturated with small bits of lye soap. Four wash tubs were lined up on a bench and filled with water which was drawn by rope and bucket from the well. The white clothes were washed, then rinsed and dumped into the pot for boiling. Next came the colored clothes, but they could not be put into the boiling pot until the whites were removed for the coloreds would usually fade. Next came the men's work clothes which were the real challenge of every wash day. They were heavy denim or duck, heavily soiled with ground-in dirt and grease from a full week's hard wear. These work clothes had to be soaked in a strong soap solution and scrubbed repeatedly on the rub board to get them clean. I have seen my mother finish many a wash day with her hands red, blistered and often bleeding, for it was her creed that it is no disgrace to wear patched clothing, but to wear them dirty is sinful.

My Mother was one-eighth Indian and a very quiet and gentle person, but she was a fanatic about cleanliness and order. She scrubbed the floors once a week with a strong soap solution. Before the floors were replaced in the old farm house, they were bleached and the knots stood a full inch above average floor level because of repeated scrubbing.

As soon as the breakfast dishes were put away, Mother made the beds and swept the house. Then it was time to gather vegetables from the garden for the noon meal. After the dinner (noon meal) dishes were dealt with, she had a two hour "rest period" when she could sew, wash windows, sweep the yard, or other such restful chores. She sometimes spent this time just rocking and singing to one of her babies.

Mid afternoon was the time to plan and start supper for the men would be ready to eat just after sundown and the vegetables were best when they were boiled very slowly. When the supper dishes were out of the way, her baby bathed the third time for the day and bedded down, the older kids yelled at until they washed their feet and went to bed, then she could lie down beside her man for a badly needed night's rest, hopefully uninterrupted by the whimpering of a fretful child. Such was the day to day struggle that was my

Mother's life and she would not have exchanged it for the life of a queen for this was her destiny.

Two machine age innovations came to the farm during my Father's working years. Others would come, but the first was a 1924 model T truck rigged for hauling logs. He worked in the timber business during the off season to supplement the farm income, and the truck enabled him to increase that supplementary income considerably. He later owned two or three different model T touring cars which were the pride of the family, as well as a farm work horse, for he hauled fresh vegetables to market in them. The second innovation was the battery-powered radio. It did not come to our house early, but two or three neighbors in the community owned one and I walked many times, on a Saturday night, to the home of a neighbor to listen to the radio. The first radio I encountered was in the home of Aunt Lizzie and Uncle Tom Mosley in 1927. It was an Atwater Kent with a morning glory horn and I surreptitiously peeked in the back of the cabinet looking for the people who were talking. The favorite program down on the farm was the "Grand Ole Opry" on Saturday nights.

The great depression of the 1930s was felt on the farm later and to a lesser degree than in the cities. In the city the family bread winner lost his job suddenly and the family had no recourse except to get in the soup line. On the farm, life's three essentials - food, clothing, and shelter - came directly or indirectly from the land. It meant that we had to work harder and get by with less, especially those items that came from town that cost money. Life on the farm was never easy and it would become even less so during the depression years.

Father was made acutely aware that hard times were upon him in 1933 when younger brother, Earnest G. Raulston, returned to the farm looking for a place to live and the chance to earn sustenance for his family. The next year the other brother, George Farris, returned with his family to seek a new start.

Grandfather William G. had acquired a tract of land across the road North of the home place. The two tracts comprised a total of over two hundred twenty-five acres which was divided between the three brothers in 1934, each taking seventy-five acres more or less. Farris moved into a house across the road that had previously been used as a house for share-croppers. Earnest took the Northeast tract and built his home there.

In 1934 my parents had a family of four boys and a girl. Betty Katherine Raulston was bom September 13, 1924. She died June 2, 1934. In the weeks following the funeral, my Father found it very difficult to come up with the sixty-five dollars he owed for the casket. A badly needed milk cow, stock feed, and other produce had to be sold. My Mother was never the same sweet, pacific person, even after her terrible grief had been assuaged by the soothing lotion of fading memories.

It was a great joy and comfort to her when on August 24, 1938, a second daughter, Cora Sue was born.

In the depression years money was very scarce throughout the nation. This caused prices to be very low. Some prices I remember are: a 48 pound bag of flour cost 65 cents, gasoline was 9 cents per gallon, and cigarettes (ready-rolls) were 12 cents a pack, a boy's overalls were 75 cents, a spool of thread was 5 cents, and ten hours hard work at the sawmill got you 75 cents.

The war years, starting in 1941, brought relief from the depression and Anxiety to every mother's heart. I was too short to get into uniform so served in a civilian capacity with the military across the nation and in the Hawiian Islands. My Mother's letters to me were so filled with worry and concern that I sometimes got the impression that she thought I was at the front.

My brother, Garland, enlisted in the Navy and served three years as a dry-land sailor. He even did a short tour in the desert at a place called Twenty-nine Palms in California. During the war years my Father was one of the few men back home who did not work in a defense job. By this time his farming operation had turned to stock farming, some romanticists call it ranching. He supplemented this income by working at the local sawmill and by independently operating in the timber business. He had two sons and a daughter who had yet to finish high school, and the increasing demands of an escalating economy had to be met. He too worried about the war and listened attentively to the news at every opportunity.

In late 1945 and early 1946 "Johnny came marching home" by the thousands. Our parents were inclined to lean back and let the boys take over. I fear that we were a great disappointment to them for we felt that a lot of living, lost in a regimented life, had to be regained. My parents were concerned but very patient with me during these years when my chief interests were fast cars and fun-loving girls. By working in a radio repair shop for a local appliance mart, I was able to stretch my funds for two years of fun and games. I was then forced to seek more gainful employment in order to pursue a more respectable niche for myself in the social order. In 1950 both of my brothers had finished school and were away from home making their own life.

In the middle 1950s, my sister, Sue, completed high school. Her graduation must have been a joyous occasion for my parents for one of their primary goals had been achieved, all of their living children had graduated from high school.

When Sue married in 1956 my parents were alone for the first time in their entire life together. Their loneliness was tempered somewhat by frequent visits from sons and grandchildren. Cora Sue Raulston Boone and husband, James, were in the Air Force at the time and were therefore not able to visit the home folk so often.

After James' discharge from service they moved back home. Their timing was fortunate for Mother's health was failing rapidly. I think that very few, if any, of the people concerned realize what a tremendous service James and Sue rendered the family by being there to care for Mother the two or three years prior to her death. After Mother's death, James and Sue built a new home on the Northeast corner of the Raulston homestead tract and Father moved in with them. We were pleased to have them move into a comfortable new home but our pleasure was accompanied by a sadness because after one hundred and thirteen years of continuously providing shelter for four generations of Raulstons, the old home was abandoned. There is nothing in this world which looks more lonesome than an abandoned house, especially if that house was your home for the first twenty years of your life. I feel pangs of remorse and guilt each time I look at it, for although it is not economically feasible to repair or rebuild the old house, it seems a disgrace and a shame to allow it to rot away."

Nannie Bess DOB: August 7, 1897

Married: April 7, 1915

Nannie Bess died: March 25, 1962

Age: 64 years, 7 months, 18 days.

Buried: 27 March 1962.

(Date of death on grave stone says March 25th. Death certificate says March 26th).

Nannie Bess Yarbrough's parents were:

Will J. Yarbrough m. Bettie Bell White on September 13, 1896

Will was born March 4, 1873 and died in 1951

Nannie Bess Yarbrough's Paternal grandparents were:

John Newton Yarbrough (born in 1846) m. Sara Adeline Doster (born January 7, 1850)

Married in 1867

John died on June 11, 1921. Sara died on August 17, 1913

Married to Clarence Melvin Raulston, Jr.

Children: Two infant daughters, Clarence Melvin Raulston, Jr., Katie Raulston (died age 10), Willie Garland Raulston, Herbert Wayne (Hub) Raulston, Kent Raulston, and Cora Sue Raulston Boone.

[Uncle C.M. wrote the following via e-mail to Paula Raulston Duchesne for the purpose of adding to our website.]

"My name is Clarence Melvin Raulston, Jr. I was born October 15, 1920 at Dimple, on the Raulston Homestead, in the house where my father and his father were born. My father was Clarence Melvin Raulston Sr.(1894-1978).

When I was about 14 years old he told me and a couple of other boys the following story.

*******************************************

In the spring of 1914 I was at the church and we had all stood up to sing the first hymn when the door was pushed open and someone entered. As was the custom then, everyone turned to see who had entered. It was the family of William Joseph Yarbrough who was new in the community. Walking beside her mother was the prettiest little gal I had ever seen in my life!

She wasn't more than five feet tall with black hair and sparkling brown eyes that seemed to be looking straight at me. I blushed a little and told myself, " I'm gonna wait for that little gal, she can't be more than fourteen and already ready built like a brick chicken house! After the service I discovered she was almost seventeen and we commenced to sparking right there". Mr. Yarbrough had bought the John C. Raulston place which put the girl next door west of Clarence.

Mr. Yarbrough had a habit which was admired by most but proved to be his ruination. It was his custom to roll out of bed before daybreak and straightaway buiId a fire in the woodburning cookstove, then go to the living room where he lighted the coal-oil lamp and proceeded to study his Bible for about fifteen minutes before rousing up his wife. Being a man of the Fannin County Prairie, Mr. Yarbrough did not know what would happen if one overcharged a cookstove with dry pine wood. His Bible study period was almost over before he became aware of the fire which had already involved the whole south end of the kitchen. They got all the kids out but were able to save very little else. Mr. Yarbrough sold out immediately to Jimmie D. Raulston and loaded his family onto the train bound for Windom in Fannin County. Clarence was mighty blue when that train pulled out with his tearful little sweetheart on board. (That experience, I am sure, was the cause of his comment to me on several occasions as we walked from the barn towards the house on those damp, cold and foggy mornings when the acoustics were such that the train going west from Clarksville sounded like it was no more than a mile away. When those old time engineers blew the whistle at approaching road crossings they had a way of making those old steamwhistles sound like the wail of a swampangel searching for a lost child. Daddv would turn toward the sound and exclaim "LORD ALMIGHTY! I wish they wouldn't do that, there's not a more lonesome sound in this world than the sound of a trainwhistle going away".)

He had a widowed sister with three Young children in addition to two younger brothers living with him which made it impractical for him to get married, but he had an understanding with the young lady that he would travel to her father's home and get permission to marry her just as soon as he possibly could. She promised to wait faithfully until that joyous day arrived. During the winter of 1914-1915, The sister, Mattie Max Raulston Brady, got herself engaged to a widower who had been courting her for almost a year. They would leave for Gallup, New Mexico in the spring. The eldest of the two brothers, Ernest, obtained gainful employment in the County Seat and moved out. On April 6, 1915 Clarence loaded a fattened hog into the wagon and headed for town. He had thirty cents in his pocket when he departed the farm. He sold the hog for $15.00, drove his wagon and team to the mulebarn and hotfooted to the railroad station in time to board the train outbound for Windom. His arrival in Windom was late in the day so he put up for the night with The Fletcher Yarbrough family, an uncle of the bride to be. Next day he rented a buggy and a highstepping black gelding in Windom and drove out to the farm south of town. After he had visited a decent amount of time with the family he loaded his intended and her luggage into the rig and drove to Honey Grove where on April 15, 1915 he married Nannie Bess Yarbrough sitting in the rig on the public square.

Nannie Bess was quite popular in Honey Grove and a small crowd gathered around the buggy to witness the ceremony. They returned to Clarksville by train, picked up the wagon and team at the mulebarn and arrived at the farm after dark. I feel certain Mattie May had a hot meal waiting on the back of the stove. Next day Clarence discovered he had thirty-seven cents in his pocket. He reported to his bride they had made seven cents on the trip.

There are unwritten facts running between the lines in this story. First, modes of transport. In 1915 there were probably fewer than 100 motor vehicles in all of Red River County. Travel from city to village, however short the distance, if the railroad went there, you traveled by train.,, Local travel was on unimproved County Roads by horseback, horse and buggy or wagon and team. It was much slower and uncomfortable but a lot safer and much more tranquil. Didn't have much highway rage then. Second, Economics. People did not buy things which were not pertinent to the task at hand. The lady of the Fletcher Yarbrough house had adequate warning of Clarence's impending arrival to put his name in the pot for the evening meal, which usually involved wringing the neck of another spring chicken. He had a hearty breakfast back at the farm before daybreak. A soda-pop on the train cost ten cents and a cold sandwich came to twenty-five cents. You have to multiply those numbers by twenty to get to 2001 prices.

The youngest of the two younger brothers was Farris (1904-1957) who was a month or so shy of eleven years of age when Nannie Bess became part of the family. The two of them formed a bond which would endure the remainder of their lives. I never heard him refer to her as anything but Sis. Nannie Bess died in 1962 a few months short of age 65. They both died from coronary occlusion.

Mother and Father had two daughters die in infancy then two sons were born. In 1923 Father came down with dengue fever, commonly called "breakbone fever," and was told by his doctor that in order to survive he must change climates. He loaded his wife and two infant sons into a covered wagon and headed West. The wagon was furnished with a full size mattress, a coal bucket, and a minimum of clothing, utensils and tools. They had no specific destination in mind when they left. When they reached a point just west of old Camp Bowie, in what is now the Ridglea Section of Fort Worth, a decision had to be made. Here the road forked, one branch turning south to the Rio Grande Valley, the other pointing straight ahead to the South Plains. After a short conversation they agreed that the road going west looked better and proceeded in that direction. Twenty-seven days after their departure from their farm in Red River County they were in Lubbock, a distance of more than four hundred miles.

These two transplanted East Texans stuck it out for two years in the Lubbock area farming rented or leased land. Many were their trials and tribulations, and deep was their longing for the Piney Woods of home. Mother had to learn simple things such as it takes much longer to cook boiled vegetables at that elevation. Father had to learn to use multi-row implements such as go-devils behind a four-horse hitch. In the late summer of 1924, Clarence M., Sr., was sitting on the fence with his landlord looking across his acreage of lush cotton. They were speculating that the yield would be a bale and one-half to two bales per acre. They were also speculating that the small thunderhead approaching from the southwest might yield a cooling shower. Thirty minutes later, after a brief but very violent hailstorm, there was nothing but stubble left in the cotton fields. Father decided immediately that he would subject himself and family to no more hardships in that strange country.

He sold out lock, stock and barrel and loaded his family on a train whose destination was Red River County. They lived one year in the small town of Bagwell, and in the autumn of 1925 Father moved back to the Raulston home place where he remained until his death.

My Father often commented that it seems his accomplishments in this life have been minimal. My Wife and I have told him that for him and Mother to have reared and educated four sons and a daughter on the proceeds from a small sandy land farm in times of depression are by no means small accomplishments. Their work day started before dawn and ended after dark, and bed time was when the supper dishes were washed, for it had been a hard day and tomorrow would be another.

Wednesday's wash was the special horror of every farm wife. The day started with a fire around the cast iron wash pot filled with water and heavily saturated with small bits of lye soap. Four wash tubs were lined up on a bench and filled with water which was drawn by rope and bucket from the well. The white clothes were washed, then rinsed and dumped into the pot for boiling. Next came the colored clothes, but they could not be put into the boiling pot until the whites were removed for the coloreds would usually fade. Next came the men's work clothes which were the real challenge of every wash day. They were heavy denim or duck, heavily soiled with ground-in dirt and grease from a full week's hard wear. These work clothes had to be soaked in a strong soap solution and scrubbed repeatedly on the rub board to get them clean. I have seen my mother finish many a wash day with her hands red, blistered and often bleeding, for it was her creed that it is no disgrace to wear patched clothing, but to wear them dirty is sinful.

My Mother was one-eighth Indian and a very quiet and gentle person, but she was a fanatic about cleanliness and order. She scrubbed the floors once a week with a strong soap solution. Before the floors were replaced in the old farm house, they were bleached and the knots stood a full inch above average floor level because of repeated scrubbing.

As soon as the breakfast dishes were put away, Mother made the beds and swept the house. Then it was time to gather vegetables from the garden for the noon meal. After the dinner (noon meal) dishes were dealt with, she had a two hour "rest period" when she could sew, wash windows, sweep the yard, or other such restful chores. She sometimes spent this time just rocking and singing to one of her babies.

Mid afternoon was the time to plan and start supper for the men would be ready to eat just after sundown and the vegetables were best when they were boiled very slowly. When the supper dishes were out of the way, her baby bathed the third time for the day and bedded down, the older kids yelled at until they washed their feet and went to bed, then she could lie down beside her man for a badly needed night's rest, hopefully uninterrupted by the whimpering of a fretful child. Such was the day to day struggle that was my

Mother's life and she would not have exchanged it for the life of a queen for this was her destiny.

Two machine age innovations came to the farm during my Father's working years. Others would come, but the first was a 1924 model T truck rigged for hauling logs. He worked in the timber business during the off season to supplement the farm income, and the truck enabled him to increase that supplementary income considerably. He later owned two or three different model T touring cars which were the pride of the family, as well as a farm work horse, for he hauled fresh vegetables to market in them. The second innovation was the battery-powered radio. It did not come to our house early, but two or three neighbors in the community owned one and I walked many times, on a Saturday night, to the home of a neighbor to listen to the radio. The first radio I encountered was in the home of Aunt Lizzie and Uncle Tom Mosley in 1927. It was an Atwater Kent with a morning glory horn and I surreptitiously peeked in the back of the cabinet looking for the people who were talking. The favorite program down on the farm was the "Grand Ole Opry" on Saturday nights.

The great depression of the 1930s was felt on the farm later and to a lesser degree than in the cities. In the city the family bread winner lost his job suddenly and the family had no recourse except to get in the soup line. On the farm, life's three essentials - food, clothing, and shelter - came directly or indirectly from the land. It meant that we had to work harder and get by with less, especially those items that came from town that cost money. Life on the farm was never easy and it would become even less so during the depression years.

Father was made acutely aware that hard times were upon him in 1933 when younger brother, Earnest G. Raulston, returned to the farm looking for a place to live and the chance to earn sustenance for his family. The next year the other brother, George Farris, returned with his family to seek a new start.

Grandfather William G. had acquired a tract of land across the road North of the home place. The two tracts comprised a total of over two hundred twenty-five acres which was divided between the three brothers in 1934, each taking seventy-five acres more or less. Farris moved into a house across the road that had previously been used as a house for share-croppers. Earnest took the Northeast tract and built his home there.

In 1934 my parents had a family of four boys and a girl. Betty Katherine Raulston was bom September 13, 1924. She died June 2, 1934. In the weeks following the funeral, my Father found it very difficult to come up with the sixty-five dollars he owed for the casket. A badly needed milk cow, stock feed, and other produce had to be sold. My Mother was never the same sweet, pacific person, even after her terrible grief had been assuaged by the soothing lotion of fading memories.

It was a great joy and comfort to her when on August 24, 1938, a second daughter, Cora Sue was born.

In the depression years money was very scarce throughout the nation. This caused prices to be very low. Some prices I remember are: a 48 pound bag of flour cost 65 cents, gasoline was 9 cents per gallon, and cigarettes (ready-rolls) were 12 cents a pack, a boy's overalls were 75 cents, a spool of thread was 5 cents, and ten hours hard work at the sawmill got you 75 cents.

The war years, starting in 1941, brought relief from the depression and Anxiety to every mother's heart. I was too short to get into uniform so served in a civilian capacity with the military across the nation and in the Hawiian Islands. My Mother's letters to me were so filled with worry and concern that I sometimes got the impression that she thought I was at the front.

My brother, Garland, enlisted in the Navy and served three years as a dry-land sailor. He even did a short tour in the desert at a place called Twenty-nine Palms in California. During the war years my Father was one of the few men back home who did not work in a defense job. By this time his farming operation had turned to stock farming, some romanticists call it ranching. He supplemented this income by working at the local sawmill and by independently operating in the timber business. He had two sons and a daughter who had yet to finish high school, and the increasing demands of an escalating economy had to be met. He too worried about the war and listened attentively to the news at every opportunity.

In late 1945 and early 1946 "Johnny came marching home" by the thousands. Our parents were inclined to lean back and let the boys take over. I fear that we were a great disappointment to them for we felt that a lot of living, lost in a regimented life, had to be regained. My parents were concerned but very patient with me during these years when my chief interests were fast cars and fun-loving girls. By working in a radio repair shop for a local appliance mart, I was able to stretch my funds for two years of fun and games. I was then forced to seek more gainful employment in order to pursue a more respectable niche for myself in the social order. In 1950 both of my brothers had finished school and were away from home making their own life.

In the middle 1950s, my sister, Sue, completed high school. Her graduation must have been a joyous occasion for my parents for one of their primary goals had been achieved, all of their living children had graduated from high school.

When Sue married in 1956 my parents were alone for the first time in their entire life together. Their loneliness was tempered somewhat by frequent visits from sons and grandchildren. Cora Sue Raulston Boone and husband, James, were in the Air Force at the time and were therefore not able to visit the home folk so often.

After James' discharge from service they moved back home. Their timing was fortunate for Mother's health was failing rapidly. I think that very few, if any, of the people concerned realize what a tremendous service James and Sue rendered the family by being there to care for Mother the two or three years prior to her death. After Mother's death, James and Sue built a new home on the Northeast corner of the Raulston homestead tract and Father moved in with them. We were pleased to have them move into a comfortable new home but our pleasure was accompanied by a sadness because after one hundred and thirteen years of continuously providing shelter for four generations of Raulstons, the old home was abandoned. There is nothing in this world which looks more lonesome than an abandoned house, especially if that house was your home for the first twenty years of your life. I feel pangs of remorse and guilt each time I look at it, for although it is not economically feasible to repair or rebuild the old house, it seems a disgrace and a shame to allow it to rot away."

Family Members

-

![]()

Infant Daughter 1 To Cm & Nb Raulston

1917–1917

-

![]()

Infant 2 Cm And Nb Raulston

1918–1918

-

![]()

Clarence Melvin "Cm" Raulston Jr

1920–2003

-

![]()

Willie Garland Raulston

1922–2020

-

![]()

Bettie Kathryn "Katy" Raulston

1924–1934

-

![]()

Herbert Wayne "Hub" Raulston

1928–1993

-

![]()

Kenneth A Raulston

1930–2003

-

![]()

Cora Sue Raulston Boone

1938–2014

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement