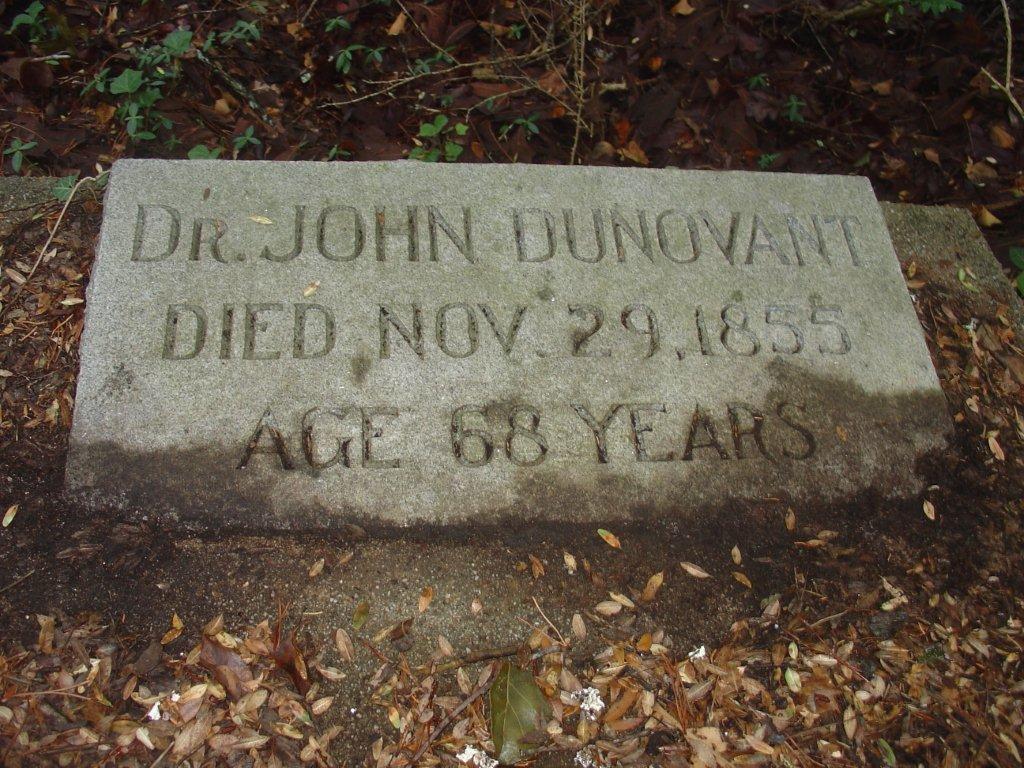

Dr. John Dunovant, of Chester, S. C., a graduate of the Philadelphia Medical College and subsequently a State Senator. His mother, Margaret Quay, was the daughter of Alexander Quay and Catherine Leslie, both of Chester, S. C. His grandfather, William Dunovant, a planter, moved from Amelia County, Va., to Chester District, S. C., the latter part of the eighteenth century.

DR. JOHN DUNOVANT’S SON, GEN, JOHN DUNOVANT HOUSTON, TEX.

FROM SKETCH BY MISS ADELIA A. DUNOVANT, Ex-PRESIDENT TEXAS DIVISION, U. D. C.

In a list of the Confederate generals published in the January (1908) issue of the CONFEDERATE VETERAN the same of one who was conspicuous for courage, brilliant in achievement, and exceptional in discipline and command of troops was not given—Brig. Gen. John Dunovant, of South Carolina. In the “Confederate Military History” there is a record of the services of this truly distinguished soldier. In the Confederate Museum at Richmond his commission is preserved. At a Confederate Reunion held in Columbia, S.C., in 1895 the eminent Maj. Gen. M. C. Butler, of South Carolina, on being requested to deliver an address, “occupied the time allotted,” to use his language, “by relating the incidents attending the death of one of the most gallant and accomplished soldiers with whom I was associated during our Civil War— Brig. Gen. John Dunovant, of Chester—with a brief and imperfect sketch of his life.” Col. U.R. Brooks' book, “Butler and His Cavalry in the War of Secession,” contains a vivid narrative of the battle of McDowell's Farm and the death of General Dunovant by one of the bravest of Confederate couriers, Charles Montague, Company B, 6th South Carolina Cavalry, Dunovant's Brigade, now living at Bandera, Tex. A circumstance following the death of General Dunovant reveals the awe in which General Dunovant was held by the enemy. The circumstance referred to in the book is as follows: “The United States Congress gave a medal to the Yankee soldier who claimed to have killed General Dunovant. A member of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry petitioned Congress for a medal, claiming that he had killed General Dunovant, and he got the medal. Colonel Kester commanded this regiment. I don't understand how a man could claim that he had killed the General when at least a thousand guns were fired at him about the same time.”

TRIBUTE FROM GENERAL BUTLER.

In his address General Butler, above referred to, said: “Gen. John Dunovant succeeded me in the command of the brigade composed of the 4th, 5th, and 6th South Carolina Cavalry, which joined the Army of Northern Virginia in April, 1864, at the opening of that desperate and trying campaign which Grant inaugurated against Richmond. General Dunovant was in command of the 5th South Carolina when the regiment reached Virginia; and, as I have remarked, was made brigadier general when I was promoted to the command of Hampton's Division, in September, 1864. “He was the beau ideal of a soldier, a knightly, chivalric gentleman, thorough in the details of discipline and order, exacting, but always just, guarding with care and solicitude the interests of his soldiers, demanding of all alike the full measure of their duty. The result was, his command was always ready to respond promptly to his orders. He was in himself a model of promptness and precision, both in obeying and executing orders. “To say that General Dunovant was able in the organization, discipline, and command C troops in battle would be no higher commendation than could be bestowed on hundreds of others. He was exceptional in those respects, and deserved higher rank than he reached. Two things conspired to prevent his advancement: First, the hostility and, I am inclined to think, jealousy of a superior officer in the early years of the war had blocked his way to promotion; and, secondly, this post of duty did not afford the opportunity for active field service, for the full exercise of his military talents. His experience in the regular army of the United States, which he left to cast his fortune with the Confederacy, prepared and qualified him for organization and putting volunteer troops in the field. “His first service in the Confederate army was as a field officer in the 1st Regiment of South Carolina Regulars, performing garrison duty in front of Charleston. This duty was of course arduous and important, and I don’t think has been properly appreciated. I have always insisted that the defense of that historic city, so full of unexampled deeds of heroism, fortitude, and gallantry, was without a parallel in military annals. The defense of Forts Moultrie and Sumter and the Morris Island Batteries against the combined attacks of the land and naval forces of the United States, when considered in all of its details, is the most remarkable in history. “But I am straying from my subject. Dunovant was for a time one of the actors in that great drama; but it was when he was transferred to the broader fields of Virginia that his talents became more conspicuous and he received the promotion to which they entitled him. “Soon after his arrival in Virginia, in 1864, he was detached with his regiment on temporary duty under command of Gen. Fitz Lee, and while so detached received a painful wound in the hand in an engagement with the enemy on the James River. Before his wound was healed he reported for duty with his hand in a sling, and never again left it until his death. “He was killed on October 1, 1864, near McDowell's farm, below Petersburg, leading his brigade, fighting as infantry, against the breastworks of the enemy. He was mounted on his favorite chestnut horse, and it was my fortune to be at his side when he received his mortal wound. General Hampton had directed me to hold a certain position on the Squirrel Level road until I heard the guns of Gen. W. H. F. Lee on my left, and then to move forward and attack all along our front. It was a cold, rainy, disagreeable day. We were dismounted, and had thrown up temporary breastworks of rails, logs, etc., and had been engaging the enemy almost the entire day, resisting repeated and determined assaults on our lines until about 3 P.M., when I ordered forward the whole line, and they went at a run down the hill, leaving the two batteries on the ridge engaged over our heads in a sharp artillery duel with the enemy's guns. Dunovant's and Young's Brigades had reached the base of the hill, where they were subjected to such a murderous fire from the enemy on the other side of a narrow swamp that I ordered the whole line to halt and lie down. I had directed Colonel Phillips to conduct his mounted regiment across a strip of woods and re-form it in an open field to our right. While the dismounted men were thus partially protected from the enemy's fire I had sent scouts to the right to ascertain if we could not find a position from which to move on the left flank of the enemy, and thus avoid a direct front attack across the swamp. “There was but one point at which a horseman could cross a narrow causeway about the center of our lines. I had ridden through the woods, a short distance to the right of the causeway, to reconnoiter the ground, and on returning met Dunovant, who remarked to me that he thought if we would make one more forward movement we could drive the enemy from this last line of works. It was then getting late in the afternoon, and I replied, ‘If that is your opinion, move your brigade forward, and then extended the order to Young. “Dunovant gave the command, ‘Attention, men, in a loud voice. They had been subjected to such a terrible fire a short time before that they were a little tardy in heeding the order. He called out a second time in tones that could not be mistaken, and every man jumped to his feet and moved forward, firing across the swamp. Dunovant's horse was fretting and careering, and mine was not behaving much better; and as we reached the causeway to cross with the line on our right and left, with an open road to the enemy's works on the other side, we were greeted with a deadly volley. Dunovant was shot, and tumbled forward from his horse on the causeway. The horse dashed forward and ran into the enemy's lines. His command, 'Forward' to his gallant soldiers was the last word he ever uttered. When the body was taken up, under the direction of his faithful and gallant adjutant general, Jeffords, I discovered an ugly indentation on his forehead, and concluded that it was there he received his mortal wound; but on examination it was found that he was shot in the breast, and the wound on the forehead must have been made by a root or log when he fell forward on the causeway. “We at once summoned Dr. Fontaine, medical director of the corps; and as he was making his way through our batteries on the hill in our rear, he was struck in the neck by the fragment of a shell from the enemy's guns, and he too paid the penalty of a faithful, fearless discharge of duty—a splendid gentleman and an accomplished officer passed to his last account. He could, however, have rendered Dunovant no service, as his gallant life went out almost in the twinkling of an eye. “This country has never had a more devoted son or gallant defender. He was one of the few men I have met in my life who seemed absolutely indifferent to the dangers and perils of battle. He was always sedate, self-composed, fearless, and ready. He died as I know he would have liked to die—with his face to the enemy and every throb of his manly, brave heart pulsating for the glory and welfare of his country.”

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FAMILY.

Gen. John Dunovant was born at Chester, S.C., on the 5th of March, 1825; and therefore was in his thirty-ninth year at the time of his death. He was the third son of Dr. John Dunovant, of Chester, S. C., a graduate of the Philadelphia Medical College and subsequently a State Senator. His mother, Margaret Quay, was the daughter of Alexander Quay and Catherine Leslie, both of Chester, S. C. His grandfather, William Dunovant, a planter, moved from Amelia County, Va., to Chester District, S. C., the latter part of the eighteenth century. Two elder brothers of General Dunovant, Col. A. Q. Dunovant and Gen. R. G. M. Dunovant (the former of Chester, the latter of Edgefield), signed South Carolina's ordinance of secession. Gen. R. G. M. Dunovant was an officer in the Mexican War. He entered the service as captain of Company B, Palmetto Regiment, and was promoted to lieutenant colonel. Some years later he was elected Adjutant and Inspector General of the State of South Carolina, in which capacity he was in command of Fort Moultrie when the “Star of the West” was fired into, and was also in command when Fort Sumter surrendered to the arms of the State.

Gen. John Dunovant served in the Mexican War as third sergeant of Company B, Palmetto Regiment; he received a severe wound at Chapultepec. He was subsequently appointed captain of Company A, 10th Infantry, United States Army, and resigned his commission upon the secession of his native State, South Carolina, giving to her the allegiance of a devoted son.

General Lee in a letter to General Hampton: “I grieve with you at the loss of General Dunovant and Dr. Fontaine, two Officers whom it will be difficult to replace.”

From Col. U. R. Brooks's book: “The greatest loss that day was General Dunovant, a brave, gallant soldier. He died leading a charge that, I believe, would have been preeminently successful had he not fallen. I have heard him since styled as rash for urging this charge; but the cool and impassive Butler gave him permission, and we subsequently succeeded in carrying with the same men the position that we then were charging when he fell, and from the increase in the enemy's fire I have always believed that subsequent to Dunovant's death and prior to our last successful charge they had been heavily reënforced. The next day General Butler started me for Chester, S.C., with the General's body, where it lies to-day at the home of his birth. No braver man ever filled a soldier's grave.

“The world shall yet decide

In truth’s clear, far-off light

That the soldiers who wore the gray and died

With Lee were in the right.’”

Gen. John Dunovant was never married. The late Capt. William Dunovant, of Texas, brother of Miss Dunovant, author of this sketch, though scarcely eighteen years of age, was appointed captain of Company C, 17th Regiment, South Carolina Volunteers, “for skill and valor.” His commission is now in the Museum at Richmond. He was intellectually developed far beyond most of his years, and was the favorite nephew of General Dunovant—a character sublime for morality, chivalry, and courage.

Through the United Daughters of the Confederacy there is distinctly a merging of the generations. These women and their successors may be expected to survive all the veterans and be perpetuated on and on for many generations.

Dr. John Dunovant, of Chester, S. C., a graduate of the Philadelphia Medical College and subsequently a State Senator. His mother, Margaret Quay, was the daughter of Alexander Quay and Catherine Leslie, both of Chester, S. C. His grandfather, William Dunovant, a planter, moved from Amelia County, Va., to Chester District, S. C., the latter part of the eighteenth century.

DR. JOHN DUNOVANT’S SON, GEN, JOHN DUNOVANT HOUSTON, TEX.

FROM SKETCH BY MISS ADELIA A. DUNOVANT, Ex-PRESIDENT TEXAS DIVISION, U. D. C.

In a list of the Confederate generals published in the January (1908) issue of the CONFEDERATE VETERAN the same of one who was conspicuous for courage, brilliant in achievement, and exceptional in discipline and command of troops was not given—Brig. Gen. John Dunovant, of South Carolina. In the “Confederate Military History” there is a record of the services of this truly distinguished soldier. In the Confederate Museum at Richmond his commission is preserved. At a Confederate Reunion held in Columbia, S.C., in 1895 the eminent Maj. Gen. M. C. Butler, of South Carolina, on being requested to deliver an address, “occupied the time allotted,” to use his language, “by relating the incidents attending the death of one of the most gallant and accomplished soldiers with whom I was associated during our Civil War— Brig. Gen. John Dunovant, of Chester—with a brief and imperfect sketch of his life.” Col. U.R. Brooks' book, “Butler and His Cavalry in the War of Secession,” contains a vivid narrative of the battle of McDowell's Farm and the death of General Dunovant by one of the bravest of Confederate couriers, Charles Montague, Company B, 6th South Carolina Cavalry, Dunovant's Brigade, now living at Bandera, Tex. A circumstance following the death of General Dunovant reveals the awe in which General Dunovant was held by the enemy. The circumstance referred to in the book is as follows: “The United States Congress gave a medal to the Yankee soldier who claimed to have killed General Dunovant. A member of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry petitioned Congress for a medal, claiming that he had killed General Dunovant, and he got the medal. Colonel Kester commanded this regiment. I don't understand how a man could claim that he had killed the General when at least a thousand guns were fired at him about the same time.”

TRIBUTE FROM GENERAL BUTLER.

In his address General Butler, above referred to, said: “Gen. John Dunovant succeeded me in the command of the brigade composed of the 4th, 5th, and 6th South Carolina Cavalry, which joined the Army of Northern Virginia in April, 1864, at the opening of that desperate and trying campaign which Grant inaugurated against Richmond. General Dunovant was in command of the 5th South Carolina when the regiment reached Virginia; and, as I have remarked, was made brigadier general when I was promoted to the command of Hampton's Division, in September, 1864. “He was the beau ideal of a soldier, a knightly, chivalric gentleman, thorough in the details of discipline and order, exacting, but always just, guarding with care and solicitude the interests of his soldiers, demanding of all alike the full measure of their duty. The result was, his command was always ready to respond promptly to his orders. He was in himself a model of promptness and precision, both in obeying and executing orders. “To say that General Dunovant was able in the organization, discipline, and command C troops in battle would be no higher commendation than could be bestowed on hundreds of others. He was exceptional in those respects, and deserved higher rank than he reached. Two things conspired to prevent his advancement: First, the hostility and, I am inclined to think, jealousy of a superior officer in the early years of the war had blocked his way to promotion; and, secondly, this post of duty did not afford the opportunity for active field service, for the full exercise of his military talents. His experience in the regular army of the United States, which he left to cast his fortune with the Confederacy, prepared and qualified him for organization and putting volunteer troops in the field. “His first service in the Confederate army was as a field officer in the 1st Regiment of South Carolina Regulars, performing garrison duty in front of Charleston. This duty was of course arduous and important, and I don’t think has been properly appreciated. I have always insisted that the defense of that historic city, so full of unexampled deeds of heroism, fortitude, and gallantry, was without a parallel in military annals. The defense of Forts Moultrie and Sumter and the Morris Island Batteries against the combined attacks of the land and naval forces of the United States, when considered in all of its details, is the most remarkable in history. “But I am straying from my subject. Dunovant was for a time one of the actors in that great drama; but it was when he was transferred to the broader fields of Virginia that his talents became more conspicuous and he received the promotion to which they entitled him. “Soon after his arrival in Virginia, in 1864, he was detached with his regiment on temporary duty under command of Gen. Fitz Lee, and while so detached received a painful wound in the hand in an engagement with the enemy on the James River. Before his wound was healed he reported for duty with his hand in a sling, and never again left it until his death. “He was killed on October 1, 1864, near McDowell's farm, below Petersburg, leading his brigade, fighting as infantry, against the breastworks of the enemy. He was mounted on his favorite chestnut horse, and it was my fortune to be at his side when he received his mortal wound. General Hampton had directed me to hold a certain position on the Squirrel Level road until I heard the guns of Gen. W. H. F. Lee on my left, and then to move forward and attack all along our front. It was a cold, rainy, disagreeable day. We were dismounted, and had thrown up temporary breastworks of rails, logs, etc., and had been engaging the enemy almost the entire day, resisting repeated and determined assaults on our lines until about 3 P.M., when I ordered forward the whole line, and they went at a run down the hill, leaving the two batteries on the ridge engaged over our heads in a sharp artillery duel with the enemy's guns. Dunovant's and Young's Brigades had reached the base of the hill, where they were subjected to such a murderous fire from the enemy on the other side of a narrow swamp that I ordered the whole line to halt and lie down. I had directed Colonel Phillips to conduct his mounted regiment across a strip of woods and re-form it in an open field to our right. While the dismounted men were thus partially protected from the enemy's fire I had sent scouts to the right to ascertain if we could not find a position from which to move on the left flank of the enemy, and thus avoid a direct front attack across the swamp. “There was but one point at which a horseman could cross a narrow causeway about the center of our lines. I had ridden through the woods, a short distance to the right of the causeway, to reconnoiter the ground, and on returning met Dunovant, who remarked to me that he thought if we would make one more forward movement we could drive the enemy from this last line of works. It was then getting late in the afternoon, and I replied, ‘If that is your opinion, move your brigade forward, and then extended the order to Young. “Dunovant gave the command, ‘Attention, men, in a loud voice. They had been subjected to such a terrible fire a short time before that they were a little tardy in heeding the order. He called out a second time in tones that could not be mistaken, and every man jumped to his feet and moved forward, firing across the swamp. Dunovant's horse was fretting and careering, and mine was not behaving much better; and as we reached the causeway to cross with the line on our right and left, with an open road to the enemy's works on the other side, we were greeted with a deadly volley. Dunovant was shot, and tumbled forward from his horse on the causeway. The horse dashed forward and ran into the enemy's lines. His command, 'Forward' to his gallant soldiers was the last word he ever uttered. When the body was taken up, under the direction of his faithful and gallant adjutant general, Jeffords, I discovered an ugly indentation on his forehead, and concluded that it was there he received his mortal wound; but on examination it was found that he was shot in the breast, and the wound on the forehead must have been made by a root or log when he fell forward on the causeway. “We at once summoned Dr. Fontaine, medical director of the corps; and as he was making his way through our batteries on the hill in our rear, he was struck in the neck by the fragment of a shell from the enemy's guns, and he too paid the penalty of a faithful, fearless discharge of duty—a splendid gentleman and an accomplished officer passed to his last account. He could, however, have rendered Dunovant no service, as his gallant life went out almost in the twinkling of an eye. “This country has never had a more devoted son or gallant defender. He was one of the few men I have met in my life who seemed absolutely indifferent to the dangers and perils of battle. He was always sedate, self-composed, fearless, and ready. He died as I know he would have liked to die—with his face to the enemy and every throb of his manly, brave heart pulsating for the glory and welfare of his country.”

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FAMILY.

Gen. John Dunovant was born at Chester, S.C., on the 5th of March, 1825; and therefore was in his thirty-ninth year at the time of his death. He was the third son of Dr. John Dunovant, of Chester, S. C., a graduate of the Philadelphia Medical College and subsequently a State Senator. His mother, Margaret Quay, was the daughter of Alexander Quay and Catherine Leslie, both of Chester, S. C. His grandfather, William Dunovant, a planter, moved from Amelia County, Va., to Chester District, S. C., the latter part of the eighteenth century. Two elder brothers of General Dunovant, Col. A. Q. Dunovant and Gen. R. G. M. Dunovant (the former of Chester, the latter of Edgefield), signed South Carolina's ordinance of secession. Gen. R. G. M. Dunovant was an officer in the Mexican War. He entered the service as captain of Company B, Palmetto Regiment, and was promoted to lieutenant colonel. Some years later he was elected Adjutant and Inspector General of the State of South Carolina, in which capacity he was in command of Fort Moultrie when the “Star of the West” was fired into, and was also in command when Fort Sumter surrendered to the arms of the State.

Gen. John Dunovant served in the Mexican War as third sergeant of Company B, Palmetto Regiment; he received a severe wound at Chapultepec. He was subsequently appointed captain of Company A, 10th Infantry, United States Army, and resigned his commission upon the secession of his native State, South Carolina, giving to her the allegiance of a devoted son.

General Lee in a letter to General Hampton: “I grieve with you at the loss of General Dunovant and Dr. Fontaine, two Officers whom it will be difficult to replace.”

From Col. U. R. Brooks's book: “The greatest loss that day was General Dunovant, a brave, gallant soldier. He died leading a charge that, I believe, would have been preeminently successful had he not fallen. I have heard him since styled as rash for urging this charge; but the cool and impassive Butler gave him permission, and we subsequently succeeded in carrying with the same men the position that we then were charging when he fell, and from the increase in the enemy's fire I have always believed that subsequent to Dunovant's death and prior to our last successful charge they had been heavily reënforced. The next day General Butler started me for Chester, S.C., with the General's body, where it lies to-day at the home of his birth. No braver man ever filled a soldier's grave.

“The world shall yet decide

In truth’s clear, far-off light

That the soldiers who wore the gray and died

With Lee were in the right.’”

Gen. John Dunovant was never married. The late Capt. William Dunovant, of Texas, brother of Miss Dunovant, author of this sketch, though scarcely eighteen years of age, was appointed captain of Company C, 17th Regiment, South Carolina Volunteers, “for skill and valor.” His commission is now in the Museum at Richmond. He was intellectually developed far beyond most of his years, and was the favorite nephew of General Dunovant—a character sublime for morality, chivalry, and courage.

Through the United Daughters of the Confederacy there is distinctly a merging of the generations. These women and their successors may be expected to survive all the veterans and be perpetuated on and on for many generations.

Family Members

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement