French Educator and Inventor. He is best remembered as the creator of a system of reading and writing for use by the blind or visually impaired, known simply as Braille.

Born the youngest of four children, his father maintained a successful business as a leather worker and maker of horse tack. At the age of three, he injured one of his eyes with an awl in his father's workshop, and after a few weeks, it became severely infected and spread to the other eye, likely due to sympathetic ophthalmia (inflammation of the eye). By the age of five, he was completely blind in both eyes.

He learned to navigate the village and country paths with canes his father hewed for him, and he grew up seemingly at peace with his disability. His bright and creative mind impressed the local teachers and priests, and he was accommodated with higher education. He studied locally until the age of 10 and, in February 1819, he was allowed to attend one of the first schools for blind children in the world, the Royal Institute for Blind Youth (now the National Institute for Blind Youth in Paris). There, he was taught how to read by a system devised by the school's founder, Valentin Haüy. Not blind himself, Haüy was a committed philanthropist who devoted his life to helping the blind. He designed and manufactured a small library of books for the children using a technique of embossing heavy paper with the raised imprints of Latin letters. Readers would trace their fingers over the text, comprehending slowly, but in a traditional fashion which Haüy could appreciate.

While helped by Haüy's books, Braille was disappointed over their lack of depth, their cumbersome size and weight, and that there was no way he could learn how to write. Despite these drawbacks, he proved to be a highly proficient student and, after he had exhausted the school's curriculum, in 1821, he learned of a communication system devised by Captain Charles Barbier de la Serre of the French Army called "night writing" which was a code of dots and dashes impressed into thick paper. These impressions could be interpreted entirely by the fingers, letting soldiers share information on the battlefield without having light or needing to speak.

The captain's code turned out to be too complex to use in its original military form, but it inspired Braille to develop a system of his own. By 1824, when he was just 15 years of age, his system was completed. He innovated Barbier's night writing by simplifying its form and maximizing its efficiency, making uniform columns for each letter and reducing the 12 raised dots to six. He published his system in 1829, and by the second edition in 1837, he had discarded the dashes because they were too difficult to read. Crucially, Braille's smaller cells were capable of being recognized as letters with a single touch of a finger.

His ear for music enabled him to become an accomplished cellist and organist in classes taught by Jean-Nicholas Marrigues. The system was soon extended to include Braille musical notation. Passionate about his own music, he took extreme care in its planning to ensure that the musical code would be "flexible enough to meet the unique requirements of any instrument." In 1829, he published the first book about his system, "Method of Writing Words, Music, and Plain Songs by Means of Dots, for Use by the Blind and Arranged for Them."

He was asked to remain at the Royal Institute as a teacher's aide and, by 1833, was elevated to a full professorship. For much of the rest of his life, Braille stayed at the Institute, where he taught history, geometry, and algebra. His other Braille books include the mathematical guide "Little Synopsis of Arithmetic for Beginners" (1838) and his monograph "New Method for Representing by Dots the Form of Letters, Maps, Geometric Figures, Musical Symbols, etc., for Use by the Blind" (1839). Later in life, his musical talents led him to play the organ for churches all over France and eventually held the position of organist in Paris at the Church of Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs from 1834 to 1839, and later at the Church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul.

Although he was admired and respected by his students, his writing system was not taught at the Royal Institute during his lifetime. The successors of Valentin Haüy, who had died in 1822, showed no interest in altering the established methods of the school and were actively hostile to its use.

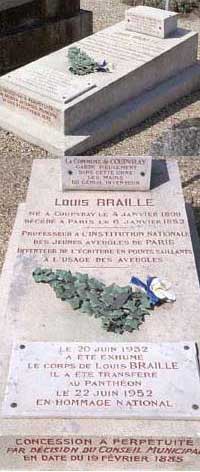

He had always been a sickly child, and his condition worsened in adulthood. A persistent respiratory illness, long believed to be tuberculosis, dogged him, and by the age of 40, he was forced to relinquish his position as a teacher. When his condition proved to be mortal, he was taken back to his family home in Coupvray, where he died at the age of 43.

Through the overwhelming insistence of the blind pupils, his system was finally adopted by the Royal Institute in 1854, two years after his death. The system spread throughout the French-speaking world, but was slower to expand in other places. In 1916, Braille was officially adopted by schools for the blind in the United States, and a universal Braille code for English was formalized in 1932.

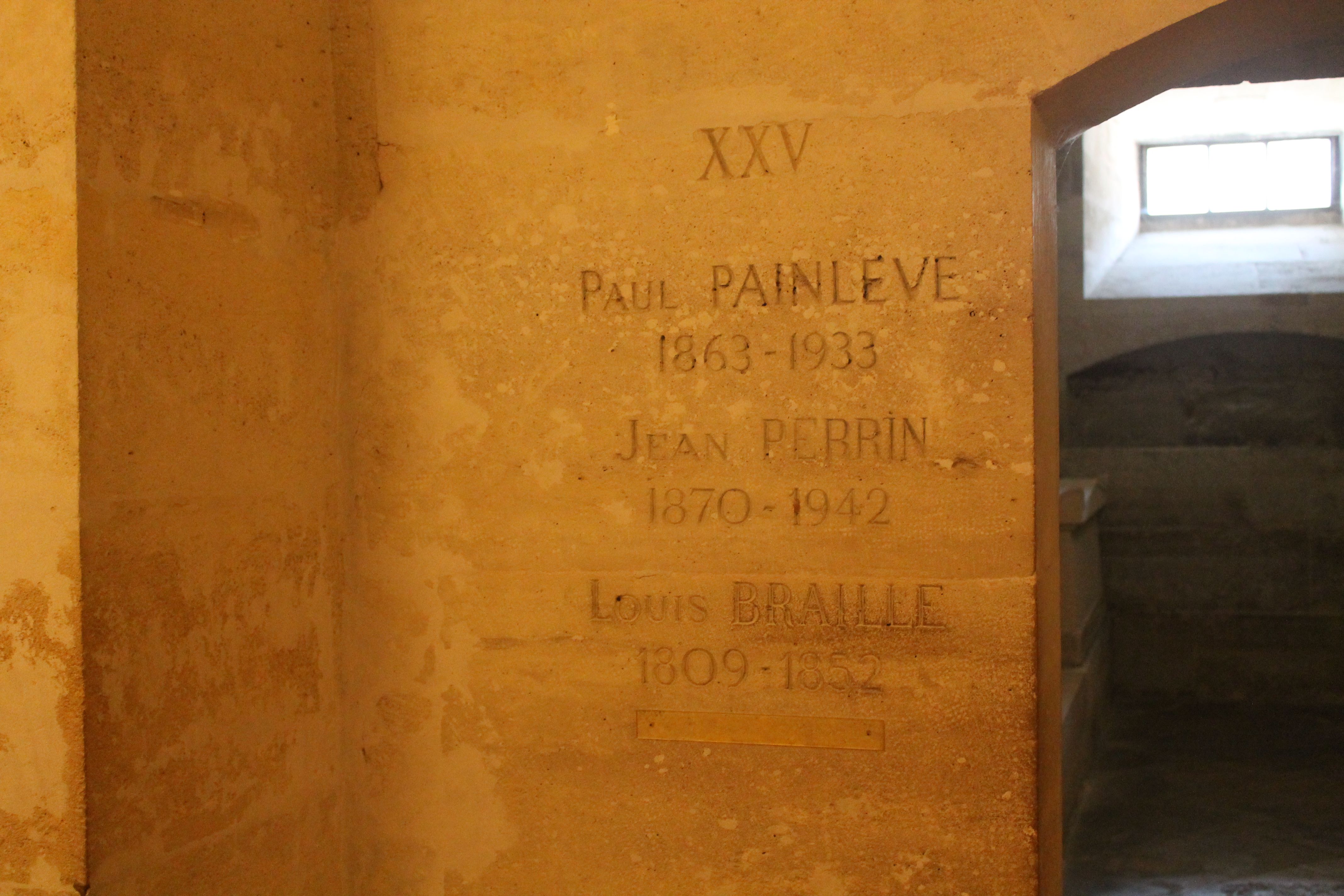

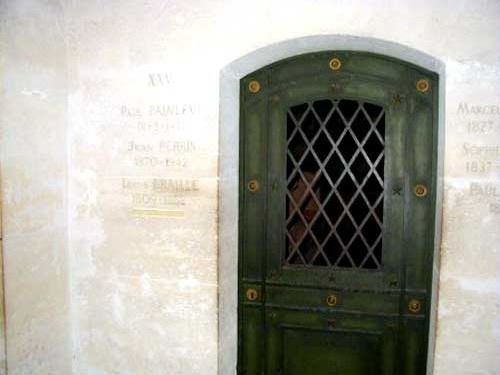

His childhood home in Coupvray is a listed historic building and houses the Louis Braille Museum. A large monument was erected in his honor in the town square, which was renamed Braille Square. On the centenary of his death, his remains were moved to the Panthéon in the Latin Quarter in Paris. In a symbolic gesture, his hands were left in Coupvray, reverently buried near his home. He was featured in the 2009 Belgian Commemorative 2 Euro Coin.

French Educator and Inventor. He is best remembered as the creator of a system of reading and writing for use by the blind or visually impaired, known simply as Braille.

Born the youngest of four children, his father maintained a successful business as a leather worker and maker of horse tack. At the age of three, he injured one of his eyes with an awl in his father's workshop, and after a few weeks, it became severely infected and spread to the other eye, likely due to sympathetic ophthalmia (inflammation of the eye). By the age of five, he was completely blind in both eyes.

He learned to navigate the village and country paths with canes his father hewed for him, and he grew up seemingly at peace with his disability. His bright and creative mind impressed the local teachers and priests, and he was accommodated with higher education. He studied locally until the age of 10 and, in February 1819, he was allowed to attend one of the first schools for blind children in the world, the Royal Institute for Blind Youth (now the National Institute for Blind Youth in Paris). There, he was taught how to read by a system devised by the school's founder, Valentin Haüy. Not blind himself, Haüy was a committed philanthropist who devoted his life to helping the blind. He designed and manufactured a small library of books for the children using a technique of embossing heavy paper with the raised imprints of Latin letters. Readers would trace their fingers over the text, comprehending slowly, but in a traditional fashion which Haüy could appreciate.

While helped by Haüy's books, Braille was disappointed over their lack of depth, their cumbersome size and weight, and that there was no way he could learn how to write. Despite these drawbacks, he proved to be a highly proficient student and, after he had exhausted the school's curriculum, in 1821, he learned of a communication system devised by Captain Charles Barbier de la Serre of the French Army called "night writing" which was a code of dots and dashes impressed into thick paper. These impressions could be interpreted entirely by the fingers, letting soldiers share information on the battlefield without having light or needing to speak.

The captain's code turned out to be too complex to use in its original military form, but it inspired Braille to develop a system of his own. By 1824, when he was just 15 years of age, his system was completed. He innovated Barbier's night writing by simplifying its form and maximizing its efficiency, making uniform columns for each letter and reducing the 12 raised dots to six. He published his system in 1829, and by the second edition in 1837, he had discarded the dashes because they were too difficult to read. Crucially, Braille's smaller cells were capable of being recognized as letters with a single touch of a finger.

His ear for music enabled him to become an accomplished cellist and organist in classes taught by Jean-Nicholas Marrigues. The system was soon extended to include Braille musical notation. Passionate about his own music, he took extreme care in its planning to ensure that the musical code would be "flexible enough to meet the unique requirements of any instrument." In 1829, he published the first book about his system, "Method of Writing Words, Music, and Plain Songs by Means of Dots, for Use by the Blind and Arranged for Them."

He was asked to remain at the Royal Institute as a teacher's aide and, by 1833, was elevated to a full professorship. For much of the rest of his life, Braille stayed at the Institute, where he taught history, geometry, and algebra. His other Braille books include the mathematical guide "Little Synopsis of Arithmetic for Beginners" (1838) and his monograph "New Method for Representing by Dots the Form of Letters, Maps, Geometric Figures, Musical Symbols, etc., for Use by the Blind" (1839). Later in life, his musical talents led him to play the organ for churches all over France and eventually held the position of organist in Paris at the Church of Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs from 1834 to 1839, and later at the Church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul.

Although he was admired and respected by his students, his writing system was not taught at the Royal Institute during his lifetime. The successors of Valentin Haüy, who had died in 1822, showed no interest in altering the established methods of the school and were actively hostile to its use.

He had always been a sickly child, and his condition worsened in adulthood. A persistent respiratory illness, long believed to be tuberculosis, dogged him, and by the age of 40, he was forced to relinquish his position as a teacher. When his condition proved to be mortal, he was taken back to his family home in Coupvray, where he died at the age of 43.

Through the overwhelming insistence of the blind pupils, his system was finally adopted by the Royal Institute in 1854, two years after his death. The system spread throughout the French-speaking world, but was slower to expand in other places. In 1916, Braille was officially adopted by schools for the blind in the United States, and a universal Braille code for English was formalized in 1932.

His childhood home in Coupvray is a listed historic building and houses the Louis Braille Museum. A large monument was erected in his honor in the town square, which was renamed Braille Square. On the centenary of his death, his remains were moved to the Panthéon in the Latin Quarter in Paris. In a symbolic gesture, his hands were left in Coupvray, reverently buried near his home. He was featured in the 2009 Belgian Commemorative 2 Euro Coin.

Bio by: William Bjornstad

Advertisement

See more Braille memorials in:

Records on Ancestry

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement