He attended Brown College and Newton Theological Institution. President of Denison College, taught at one time at Cornell University.

First a lay then ordained minister, later a professor, teacher of philosophy, Roman law, political economy and international law, author of historical books.

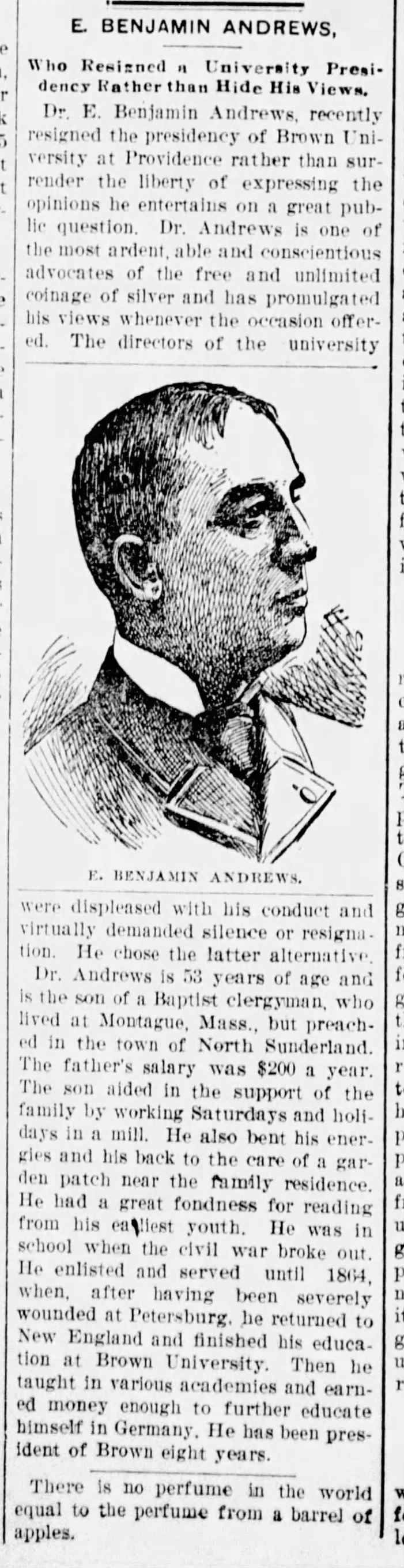

President and professor at Brown College which he directed towards becoming a university, but not without controversy over his freedom of speech right to take positions on certain issues of the day that conflicted with the views of a Brown corporate board members who wanted to his resignation and contended Andrews views undermined the ability of the school to raise endowments to make Brown into a modern university. Andrews resigned over the incident but was soon after restored to his position as President, after much alumni and public opposition to his resignation and the Brown board actions.

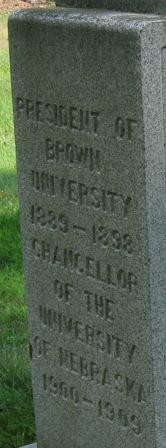

Later superintendent of Chicago public schools and chancellor of the Univ. of Nebraska until his retirement in 1908, American commissioner to the Brussels monetary conference and supporter of bimetallism, past president of the Assoc. of State Universities.

For source of the above and more information, go to: http://www.brown.edu/Administration/News_Bureau/Databases/Encyclopedia/search.php?serial=A0340

and....

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elisha_Andrews

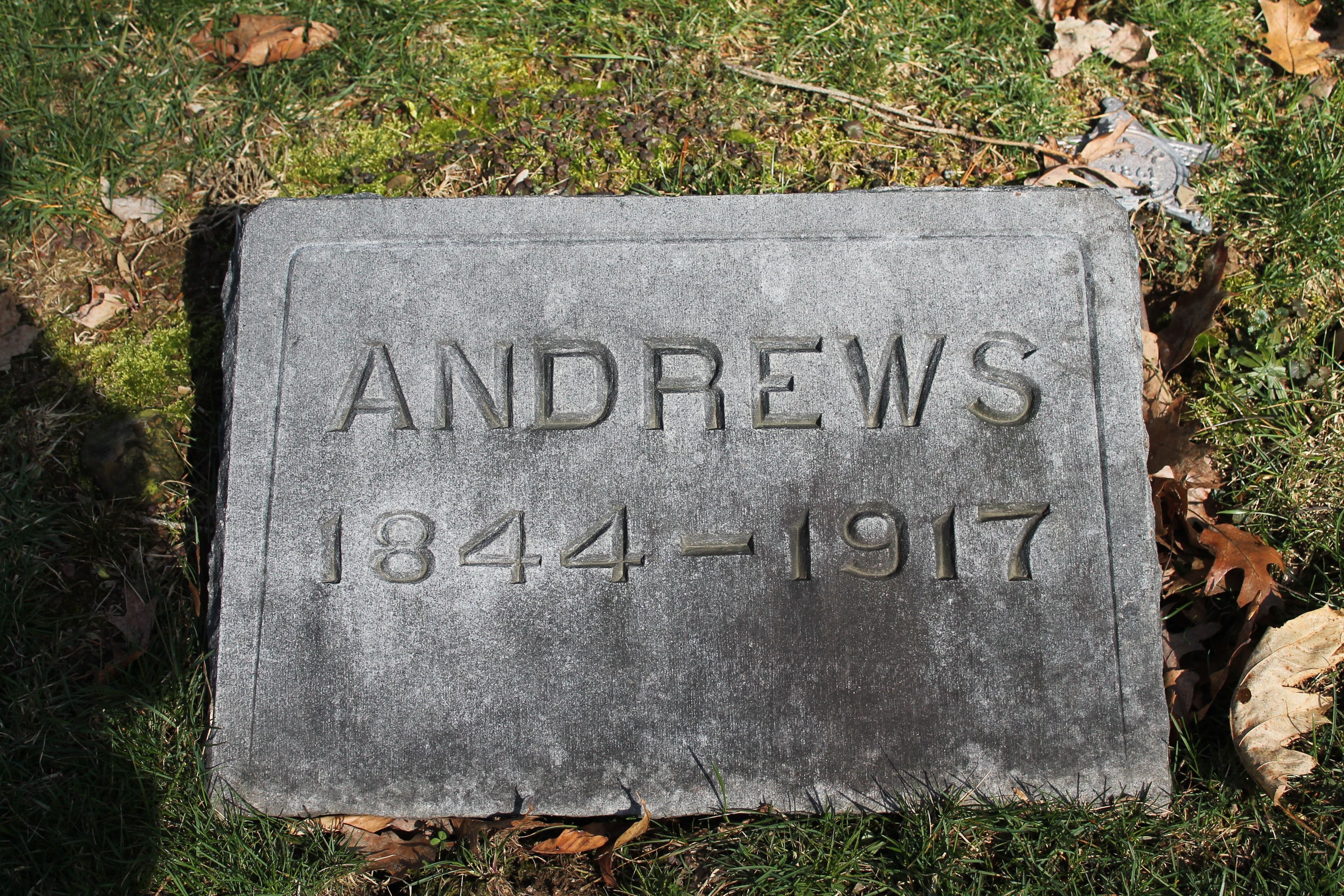

Interlachen - Dr. Benjamin Andrews passed away on the morning of October 30th, after a decline continuing for years. Remains will be taken to Granville, Ohio, for burial, under the auspices of the first college of which he was president. In the death of Dr. Andrews this country has lost one its distinguished educators and the world one of God's rarest noblemen. Further obituary notice will be given next week. (Times-Herald Obituary dtd Friday, 2 Nov 1917.)

Further obituary information:

Interlachen - Dr. Elisha Benjamin Andrews, prominent educator and writer, who for a number of years has been an invalid, passed away at his home here at an early hour Tuesday morning. He had been failing rapidly in the past two weeks, and the end was not unexpected. The remains will be taken to Ohio for interment. Dr. Andrews was chancellor emeritus of the University of Nebraska and a distinguished Baptist devine as well as educator. Before taking the presidency of the University of Nebraska he was for many years president of Dennison University of Granville, Ohio, and it is to this place that his body was shipped for interment. His son, Mr. Guy A. Andrews, is an attorney in Tampa, and he came to accompany the body north. Dr. Andrews was 73 years of age and besides the son above named he is survived by his wife and one daughter. (Palatka News Obituary dtd Friday, 2 Nov 1917.)

∼Cenotaph at the Temple Building, University of Nebraska for Dr. E.B. Andrews, Chancellor of the University of Nebraska, President of Denison and Brown Universities, professor Cornell University, superintendent of the Chicago Public Schools

In 1916 University of Nebraska Chancellor Avery asked the Board of Regents to install a plaque in the Temple Building to commemorate Andrews, but the board thought that because the Temple was a gift (from Rockefeller and the citizens of the state through their donations), the plaque should be also. After some "judicious feeling around," Avery secured support for the plaque from the class of 1915.

The plaque remains today, in the west foyer of the Temple Building. If brick and mortar could talk, or if quiet visitors would listen for the echoes emanating from the walls, the Temple would tell a remarkable story of one man's perseverance in the face of vitriolic odds.

On Tuesday, November 6, 1917, a memorial service was held for E. B. Andrews in Memorial Hall. He had died at his home in Interlachen, Florida, on October 30. The university's memorial service was scheduled to coincide with the funeral service and burial at Denison College, Granville, Ohio, site of Andrews's first college presidency. In addressing the group assembled in Nebraska, Chancellor Avery stated, "The Temple is his own peculiar gift to the University. Conceived in a highly altruistic spirit; pushed forward in the face of storm that did much to break down his health."

The Temple Building...was built during Andrews's term as chancellor. This project pitted Andrews and the regents against the press and populace of the state. Andrews contacted an acquaintance from his days at BrownJohn D. Rockefeller- and proposed that Rockefeller match $33,333.33 of locally raised funds with $66,666.66 of his own money to build a "social and religious· facility for the university. Chancellor Andrews personally bought three vacant lots at Twelfth and R streets for $5,000, the title to which he transferred to the Board of Regents in 1903.

Nearly daily from January through March 1904, the Omaha World-Herald editor attacked Andrews for having sought oil-tainted money to build a "memorial to Rockefeller.".... At the height of the World-Herald's rampage, the headlines fairly shouted through the use of heavy type and terms such as "Trickery" and "False Pretenses" and "Deceit and Duplicity....By late February, however, the tide of public opinion appeared to slowly be turning in favor of the building; by June 1904 the funds were in place and in December, construction was authorized.

Information from Anne M Oppegard, “For Posterity: Namesakes of Four University of Nebraska Buildings,” Nebraska History 78 (1997): 122-133

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The death at Interlachen, Fla., of Dr. Elisha Benjamin Andrews, formerly president of Brown University and later chancellor of the University of Nebraska, was announced in telegrams received here today.

Dr. Andrews, who was 73 years of age died early today. Broken in health after 37 years of service as an educator, he moved to Florida after resigning as chancellor of the University of Nebraska in 1908, to become chancellor emeritus. The message conveying news of his death was sent by his son Guy A. Andrews.

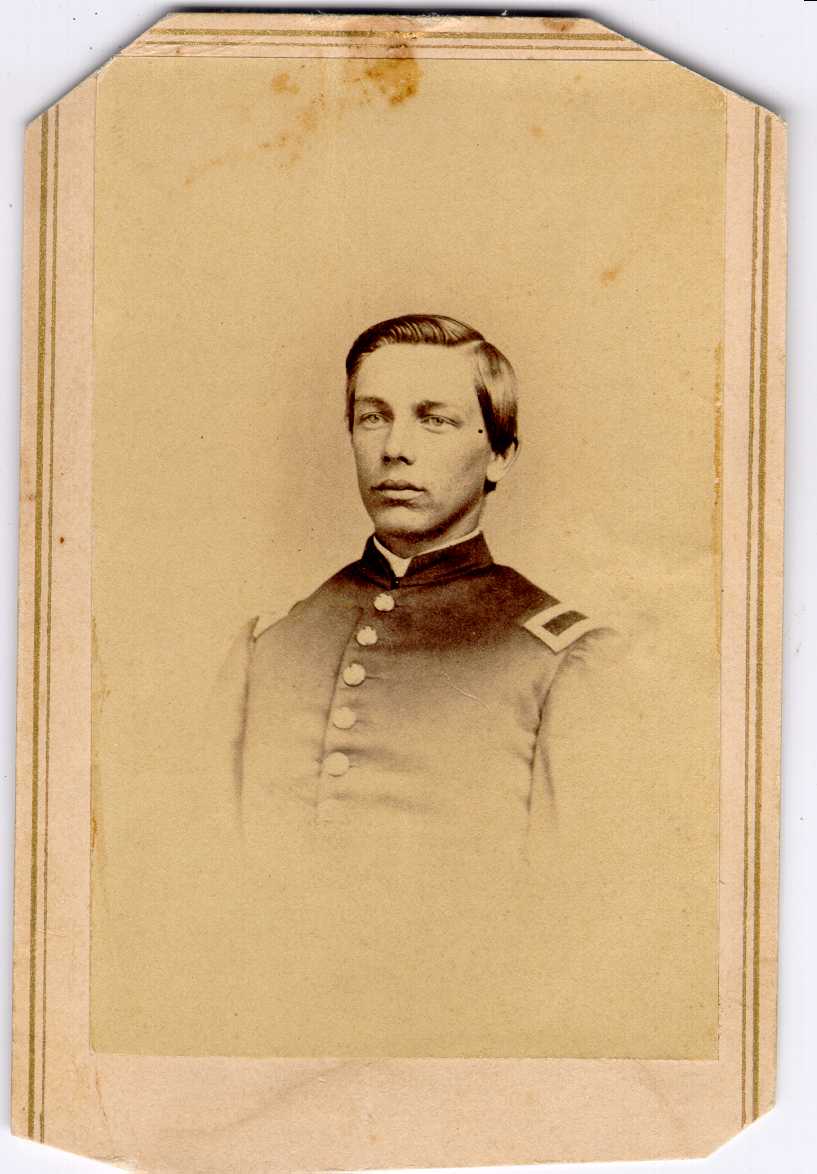

Dr. Andrews, a native of New Hampshire, saw service in the Civil War, became a lieutenant, and in 1864 was incapacitated by the loss of an eye. At the close of the war he entered Brown University and was graduated four years later. He entered Newton Theological Seminary, was ordained a minister of the Baptist Church and preached one year, resigning to become president of Denison University, Ohio.

He was subsequently a member of the faculty of Brown University and Cornell and was president of Brown from 1889 to 1898. At Cornell he served as professor of economics in 1888-1889. From Brown Dr. Andrews went to Chicago as superintendent of schools, later serving eight years as chancellor of the University of Nebraska. In 1907 he received a pension from the Carnegie foundation as a reward of his life's work.

Published in The Ithaca Journal, Ithaca New York October 30, 1917

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Elisha Benjamin Andrews was born in 1844 in Hinsdale, New Hampshire. After being severely wounded in the Civil War, permanently losing his sight in one eye, he continued his education, graduating from Brown in 1870. He was subsequently ordained as a Baptist minister but returned to Brown in 1882 as professor of history and political economy.

Andrews left for Cornell in 1888, to the great disappointment of students, but the following year was chosen unanimously to become Brown’s next president. His presidency is noted for a rapid growth in graduate studies and the transformation of Brown into what he called “a true University.”

In 1896, Nebraska populist William Jennings Bryan won the Democratic nomination for the presidency after advocating “free silver” in a speech famously proclaiming “you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” He lost the general election to Republican William McKinley, who supported the gold standard.

Andrews had supported free silver in personal letters that were published in 1896 without his knowledge or permission. In July 1897, members of Brown’s governing “Corporation” expressed their concern that his views on what had become a highly controversial political issue were so upsetting to friends of the University that they were costing gifts and legacies.

Andrews resigned immediately, but Brown faculty, students, and alumni sent petitions on his behalf, as did other college presidents. Faculty warned the Corporation that to accept the resignation “would stamp this institution, in the eyes of the country, as one in which freedom of thought and expression is not permitted when it runs counter to the views generally accepted in the community or held by those from whom the University hopes to obtain financial support.”

Andrews noted that he had not “been loud, a declaimer, parading my views, ambitiously or otherwise” but insisted as a matter of academic principle that he could not surrender his freedom of speech. The Corporation asked him to withdraw his resignation, which he did.

Nevertheless, he left the following year for Chicago where, as superintendent of the Chicago Public Schools, he freed the schools from external political controls. Then, in 1900, he was appointed Chancellor of the University of Nebraska, which he transformed over the next eight years from a rapidly growing college into a genuine university.

Along with Wisconsin and Cornell, Nebraska was known at the turn of the 20th century as a haven of dissent. Andrews immediately reinforced that reputation.

In November 1900, Edward A. Ross, who was to become one of the founders of modern sociology, was fired by Stanford University for addressing issues of social injustice. The powerful Mrs. Stanford especially objected to his concern with Chinese railroad labor, the source of the Stanford family fortune. Andrews promptly hired Ross at Nebraska.

Other Stanford professors resigned in protest of the firing, including former Nebraska professor George Howard, a staunch supporter of civil liberties who had been hired by Stanford to found its history department and had in turn hired Ross. Andrews invited Howard back to Nebraska.

Andrews also rehired Harry Kirke Wolfe, the founding father of philosophy, psychology, and education at the University of Nebraska, who had been fired in 1897 for speaking out about falsification of student enrollment data. Wolfe returned in 1906 to found the department of educational psychology and later resumed his former position as chair of philosophy.

Poor health dogged Andrews throughout his life and finally forced him to retire at the end of 1908. After his death in 1917, the renowned college president and free speech advocate Alexander Meiklejohn, an 1893 graduate of Brown, eulogized him:

“Dear, gallant, stalwart, splendid Bennie Andrews... Oh, what a gallant fight he made, and what a hard one!”

At both Brown and UNL there is an Andrews Hall named for E. Benjamin Andrews. At Brown it is a residence hall; at UNL it houses the Department of English. Both students and academe were served well by his respect for intellectual freedom in higher education.

Information from The University of Nebraska

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Elisha Benjamin Andrews came to Nebraska after a national search for George MacLean’s successor, during which Charles Bessey served again as interim chancellor. Andrews, who was then serving as the superintendent of schools for the city of Chicago, had administered distinguished institutions before. He led Denison University in Ohio from 1875 to 1879, and his alma mater Brown University as its president from 1889 to 1898.

While the university had plateaued somewhat during MacLean’s tenure after its ascendance under James Canfield, it was still a formidable institution of national stature, and it grew under Andrews' leadership. In 1900, the year that he assumed the chancellorship, Nebraska’s enrollment stood at 2,200 students – a fairly large university for the time. Under his watch, the university grew to nearly 4,000 students.

An examination of the artifacts left by the student body in Canfield’s time, and again but perhaps to a lesser extent in Andrews’, reveals a remarkably talented, inquisitive and accomplished community of scholars driven to compete on the field and in the classroom with other great universities. They were determined to make the University of Nebraska equal to some of the widely revered institutions of the time, and in this Golden Age, largely accomplished the feat. It was during Andrews' time that the university's athletic teams, known variously as the fearsome "Bugeaters" and "Rattlesnake Boys," and the more staid and traditional "Old Gold Knights" in prior years, adopted a name suggested by a local sportswriter, Charlie "Cy" Sherman – the Cornhuskers.

Academically, a culture of debate rose at the university, in which the highest undergraduate academic calling was to be a member of the team led by Miller M. Fogg. Debate today remains a competitive high school activity sanctioned by the Nebraska School Activities Association. The Innocents Society was organized in 1903, in part as a counter to Theta Nu Epsilon, an antiauthoritarian "drinking fraternity." All-male, it was joined by the women's Black Masque a few years later. Both were dedicated to advancing both the individual and the institution, and membership was highly sought after.

Andrews sought and obtained funding from John D. Rockefeller for the university's first student activities building, matched at a 2:1 ratio with state funds after Andrews defeated the famously loquacious William Jennings Bryan in the court of public opinion. Bryan had objected to accepting the charity of a robber baron, but the Temple Building was erected anyway. All told, during his years at the helm, nine new buildings were constructed under Andrews' leadership.

Andrews re-ignited the restless ferment that had previously reached its zenith under Canfield. The university grew considerably during his tenure, and by the end of his chancellorship, the University of Nebraska was the nation's fifth-largest public institution.

According to the historian Robert Knoll in his "Prairie University," "Some persons think him the greatest chancellor the University of Nebraska has ever had and one of the noblest men who have passed this way."

Never in the best of health, Andrews spent the remainder of his life in Interlachen, Florida, where he died in 1917. His body was sent back to Denison University in Ohio, where he rests in the campus cemetery. At his funeral, Alexander Meiklejohn, the philosopher, free-speech crusader and university leader, eulogized him:

“Dear, gallant, stalwart, splendid Bennie Andrews. The zest of life was in him to the brim. He loved the things a man might be. Oh, what a gallant fight he made, and what a hard one! I cannot mourn that he is gone; I am too glad that he has been and is. He was a man. Yes, take him all in all, we shall not see his like again.”

Information from the University of Nebraska

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Andrews, Elisha Benjamin

Elisha Benjamin Andrews (1844-1917), eighth president of Brown University, was born in Hinsdale, New Hampshire, on January 10, 1844. His father and grandfather were Baptist ministers. He attended the Connecticut Literary Institute in Suffield, but left to enlist in the First Connecticut Heavy Artillery when the Civil War broke out. He rose to the rank of second lieutenant, and was severely wounded in a battle on the James River on August 24, 1864. He lost the sight of his left eye, which was replaced by a glass eye in 1884. He was mustered out of the army in October 1864. He then resumed his education at the Powers Institute in Bernardston and went on to Wesleyan Academy in Wilbraham, Massachusetts. He entered Brown in 1866 at the age of 22 and graduated in 1870. He had decided to became a minister, and served as a lay preacher and Sunday school teacher while in college. After graduation he returned to Suffield as principal of the academy for two years. He graduated from Newton Theological Institution in 1874, and was ordained in Beverly, Massachusetts, where he served as pastor for one year until he was called to the presidency of Denison University in 1875. At Denison he introduced elective courses and hired William Rainey Harper, a non-Baptist, to teach. A few years later he recommended that Harper leave Denison for the Baptist Union Theological Seminary of Chicago. Andrews left Denison in 1879, possibly because his liberal ideas irritated the trustees, although he remained a trustee until 1892. He became a professor of homiletics and pastoral theology at Newton, where he remained until 1882. While still at Newton in 1882, he also taught a philosophy course at Colby College taking the place of the president, who was ill. Andrews was appointed professor of history and political economy at Brown in 1882, but was allowed a year to study in Germany, while others continued the courses formerly taught by Professor J. Lewis Diman, who had died in 1881.

Arriving at Brown in September 1883, Andrews taught the history course and electives in Roman law, political economy, and international law. He wrote two historical textbooks, Brief Institutes of Our Constitutional History, English and American in 1886, a book written for use as a students’ syllabus of his lectures, and Brief Institutes of General History in 1887, an outline of history to the late nineteenth century. His later works, the four-volume set of History of the United States, published in 1894, and The Last Quarter-Century of the United States, in 1896, were written for popular consumption and were not up to his former standards.

He was a very effective teacher and was extremely popular with the students, and many were disappointed when he left in 1888 to teach at Cornell. He was not gone for long, however, as President Robinson resigned the next year, and Andrews was unanimously elected to replace him as president and professor of moral and intellectual philosophy.

Under his administration the University made great strides. Graduate study, just begun under Robinson, grew rapidly, undergraduate enrollment increased 140 per cent in eight years, and after some years of discussion, women were finally admitted, not at first to the University, but to examinations only. Andrews saw to it that arrangements were made for classes to prepare the women for the examinations. Brown professors were hired to teach them, and room was found for their classes in the University Grammar School. In the late afternoon when that building was dark, they moved to Andrews’ own office to continue their classes.

In his annual report for 1892 Andrews, after pointing out that the chemical laboratory, the botanical laboratory, Sayles Hall, and the dormitories were all outgrown, dared to present the greatest challenge yet. He wrote, “I cannot avoid the conviction that Brown University has reached a serious crisis in its history. It stands face to face with the question whether it will remain a College and nothing more or will rise and expand into a true University.... The expression, ‘a first-rate college which is a college only,’ I believe to be a contradiction in terms.” Citing the example of German universities and the need for research as well as teaching, he stated his objectives, “It is my belief ... that our alma mater will fail of her proper privilege and destiny unless, as rapidly as is consistent with healthy development, we promote her to the estate of a true University.” He called for raising a million dollars within a year, and two million more in ten years to found fellowships for advanced students, increase faculty salaries and establish new professorships, fund the library, support a school of applied science, and equip a Women’s College.

President Keeney said of him, “Andrews succeeded at the center and failed around the edges. He brought Brown to a height that it had never previously achieved; he assembled the best Faculty and student body that had ever been seen here. ... As President of Brown he was a great and tragic figure; He saw what had to be done, did it in part, and yet could not find the means to pay for it.”

The opinion of some Corporation members that the means might be forthcoming were it not for the political views of the president led to what came to be known as “The Andrews Controversy.” Andrews believed in international bimetallism and had expressed his views before and after becoming president. In the summer of 1896 a few of his personal letters, which were published, indicated that he had adopted the position that the United States should begin the free coinage of silver at the ratio of sixteen ounces of silver to one ounce of gold, without waiting for the cooperation of other countries. When this issue became paramount in the presidential election campaign of 1896, Andrews was far away in Europe, but was being freely quoted to the dismay of Corporation members who felt that his views were adversely affecting the prospects of the University. At the Corporation meeting in June 1897 it was resolved that a committee be appointed “to confer with the president in regard to the interests of the University.” In July the meeting was held, and the committee presented, at Andrews’ request, a written statement of the concerns of several members of the Corporation, “They signified a wish for a change in only one particular, having reference to his views upon a question which constituted a leading issue in the recent Presidential election and which is still predominant in National politics ... They considered that the views of the President, as made public by him from time to time ... were so contrary to the views generally held by the friends of the University that the University had already lost gifts and legacies which would otherwise have come or been assured to it, and that without a change it would in the future fail to receive the pecuniary support which is requisite to enable it to prosecute with success the grand work on which it has entered.” They did not require a renunciation of his views as long as he did not promulgate them. Andrews resigned the next day, stating that he could not surrender his right to freedom of speech. The case attracted much attention and was discussed throughout the country. At stake was either an institution’s right to restrain its head from actions not in its interest, or the whole issue of academic freedom.

In the midst of the controversy in the summer of 1897, Andrews had also accepted the offer received from John Brisben Walker, editor of Cosmopolitan Magazine, of the presidency of his proposed “Cosmopolitan University,” a tuition-free correspondence school for the educational benefit of the public. Andrews apparently intended to undertake this new project and still remain at Brown. Ill and distressed by the turmoil about him, he spent three weeks in August confined to a sanitarium in Wethersfield, Connecticut.

Meanwhile, an open letter to the Corporation by twenty-four Brown professors urged that the resignation not be accepted lest the reaction “would stamp this institution, in the eyes of the country, as one in which freedom of thought and expression is not permitted when it runs counter to the views generally accepted in the community or held by those from whom the University hopes to obtain financial support.&8221; Six hundred alumni signed petitions that requested the Corporation to “take action upon the resignation of President Andrews which will effectually refute the charge that reasonable liberty of utterance was, or ever is to be denied to any teacher of Brown University.” Of the 49 alumnae who owed their existence to Andrews, 46 sent a similar petition, and more than a hundred college presidents, professors, and public figures signed petitions requesting the Corporation not to accept the resignation. At a meeting of the Corporation on the first of September a statement by Andrews was presented, reiterating his belief in the unilateral free coinage of silver by the United States, but pointing out that his views had come to light only through the publication of personal letters written before the presidential campaign. He summed up his situation, “That ... I have been loud, a declaimer, parading my views, ambitiously or otherwise, I emphatically deny. Unfortunate I have been: indiscreet, I believe, I have not been.” The Corporation reconsidered and wrote to Andrews, “Having ... removed the misapprehension that your individual views on this question represent those of the Corporation and the University ... the Corporation, affirming its rightful authority to conserve ‘the interests of the University’ at all times ... cannot feel that the divergence of views between you and the members of the Corporation upon the ‘silver question’ and its effect upon the University is an adequate cause of separation between us, for the Corporation is profoundly appreciative of the great services you have rendered the University and of your sacrifice and love for it. It therefore renews its assurances of highest respect for you and expresses the confident hope that you will withdraw your resignation.” Andrews replied that he would do so as the Corporation’s action “entirely does away with the scruple which led to my resignation.”

The controversy over, the president returned to his duties, and the Boston Alumni Association started a movement to raise two million dollars to rescue the sagging resources of the University. Andrews, however, did not stay to partake of such improvements. He resigned in July 1898 to become superintendent of the Chicago public schools. After two years in Chicago he was named chancellor of the University of Nebraska, which position he held until his retirement because of ill health in 1908. During his administration in Nebraska, the enrollment had risen by fifty per cent, eight new buildings were built, and the legislative appropriation to the University nearly doubled. He died after an illness of several years on October 20, 1917 in Interlachen, Florida. Alexander Meiklejohn ’93 eulogized him:

“Dear, gallant, stalwart, splendid Bennie Andrews. The zest of life was in him to the brim. He loved the things a man might be. Oh, what a gallant fight he made, and what a hard one! I cannot mourn that he is gone; I am too glad that he has been and is. He was a man. Yes, take him all in all, we shall not see his like again.”

In his speech at the dedication of Andrews Hall, President Wriston said:

“Under Andrews, Brown ceased to be a small New England college and embraced the idea of a university. With him the ideal of scholarship, which must dominate a modern university, came to fruition. Graduate work was put on a solid basis. The thorny problem of the accommodation of women was solved in a manner both statesmanlike and tactful. The principles of academic freedom were dramatized and justified not only for Brown, but for all universities and colleges.... Is it any wonder that the largest building on the Pembroke campus is now named ‘Andrews Hall’?”

Information from Brown University/Encyclopedia Brunoniana by Martha Mitchell, Brown University Library.

He attended Brown College and Newton Theological Institution. President of Denison College, taught at one time at Cornell University.

First a lay then ordained minister, later a professor, teacher of philosophy, Roman law, political economy and international law, author of historical books.

President and professor at Brown College which he directed towards becoming a university, but not without controversy over his freedom of speech right to take positions on certain issues of the day that conflicted with the views of a Brown corporate board members who wanted to his resignation and contended Andrews views undermined the ability of the school to raise endowments to make Brown into a modern university. Andrews resigned over the incident but was soon after restored to his position as President, after much alumni and public opposition to his resignation and the Brown board actions.

Later superintendent of Chicago public schools and chancellor of the Univ. of Nebraska until his retirement in 1908, American commissioner to the Brussels monetary conference and supporter of bimetallism, past president of the Assoc. of State Universities.

For source of the above and more information, go to: http://www.brown.edu/Administration/News_Bureau/Databases/Encyclopedia/search.php?serial=A0340

and....

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elisha_Andrews

Interlachen - Dr. Benjamin Andrews passed away on the morning of October 30th, after a decline continuing for years. Remains will be taken to Granville, Ohio, for burial, under the auspices of the first college of which he was president. In the death of Dr. Andrews this country has lost one its distinguished educators and the world one of God's rarest noblemen. Further obituary notice will be given next week. (Times-Herald Obituary dtd Friday, 2 Nov 1917.)

Further obituary information:

Interlachen - Dr. Elisha Benjamin Andrews, prominent educator and writer, who for a number of years has been an invalid, passed away at his home here at an early hour Tuesday morning. He had been failing rapidly in the past two weeks, and the end was not unexpected. The remains will be taken to Ohio for interment. Dr. Andrews was chancellor emeritus of the University of Nebraska and a distinguished Baptist devine as well as educator. Before taking the presidency of the University of Nebraska he was for many years president of Dennison University of Granville, Ohio, and it is to this place that his body was shipped for interment. His son, Mr. Guy A. Andrews, is an attorney in Tampa, and he came to accompany the body north. Dr. Andrews was 73 years of age and besides the son above named he is survived by his wife and one daughter. (Palatka News Obituary dtd Friday, 2 Nov 1917.)

∼Cenotaph at the Temple Building, University of Nebraska for Dr. E.B. Andrews, Chancellor of the University of Nebraska, President of Denison and Brown Universities, professor Cornell University, superintendent of the Chicago Public Schools

In 1916 University of Nebraska Chancellor Avery asked the Board of Regents to install a plaque in the Temple Building to commemorate Andrews, but the board thought that because the Temple was a gift (from Rockefeller and the citizens of the state through their donations), the plaque should be also. After some "judicious feeling around," Avery secured support for the plaque from the class of 1915.

The plaque remains today, in the west foyer of the Temple Building. If brick and mortar could talk, or if quiet visitors would listen for the echoes emanating from the walls, the Temple would tell a remarkable story of one man's perseverance in the face of vitriolic odds.

On Tuesday, November 6, 1917, a memorial service was held for E. B. Andrews in Memorial Hall. He had died at his home in Interlachen, Florida, on October 30. The university's memorial service was scheduled to coincide with the funeral service and burial at Denison College, Granville, Ohio, site of Andrews's first college presidency. In addressing the group assembled in Nebraska, Chancellor Avery stated, "The Temple is his own peculiar gift to the University. Conceived in a highly altruistic spirit; pushed forward in the face of storm that did much to break down his health."

The Temple Building...was built during Andrews's term as chancellor. This project pitted Andrews and the regents against the press and populace of the state. Andrews contacted an acquaintance from his days at BrownJohn D. Rockefeller- and proposed that Rockefeller match $33,333.33 of locally raised funds with $66,666.66 of his own money to build a "social and religious· facility for the university. Chancellor Andrews personally bought three vacant lots at Twelfth and R streets for $5,000, the title to which he transferred to the Board of Regents in 1903.

Nearly daily from January through March 1904, the Omaha World-Herald editor attacked Andrews for having sought oil-tainted money to build a "memorial to Rockefeller.".... At the height of the World-Herald's rampage, the headlines fairly shouted through the use of heavy type and terms such as "Trickery" and "False Pretenses" and "Deceit and Duplicity....By late February, however, the tide of public opinion appeared to slowly be turning in favor of the building; by June 1904 the funds were in place and in December, construction was authorized.

Information from Anne M Oppegard, “For Posterity: Namesakes of Four University of Nebraska Buildings,” Nebraska History 78 (1997): 122-133

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The death at Interlachen, Fla., of Dr. Elisha Benjamin Andrews, formerly president of Brown University and later chancellor of the University of Nebraska, was announced in telegrams received here today.

Dr. Andrews, who was 73 years of age died early today. Broken in health after 37 years of service as an educator, he moved to Florida after resigning as chancellor of the University of Nebraska in 1908, to become chancellor emeritus. The message conveying news of his death was sent by his son Guy A. Andrews.

Dr. Andrews, a native of New Hampshire, saw service in the Civil War, became a lieutenant, and in 1864 was incapacitated by the loss of an eye. At the close of the war he entered Brown University and was graduated four years later. He entered Newton Theological Seminary, was ordained a minister of the Baptist Church and preached one year, resigning to become president of Denison University, Ohio.

He was subsequently a member of the faculty of Brown University and Cornell and was president of Brown from 1889 to 1898. At Cornell he served as professor of economics in 1888-1889. From Brown Dr. Andrews went to Chicago as superintendent of schools, later serving eight years as chancellor of the University of Nebraska. In 1907 he received a pension from the Carnegie foundation as a reward of his life's work.

Published in The Ithaca Journal, Ithaca New York October 30, 1917

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Elisha Benjamin Andrews was born in 1844 in Hinsdale, New Hampshire. After being severely wounded in the Civil War, permanently losing his sight in one eye, he continued his education, graduating from Brown in 1870. He was subsequently ordained as a Baptist minister but returned to Brown in 1882 as professor of history and political economy.

Andrews left for Cornell in 1888, to the great disappointment of students, but the following year was chosen unanimously to become Brown’s next president. His presidency is noted for a rapid growth in graduate studies and the transformation of Brown into what he called “a true University.”

In 1896, Nebraska populist William Jennings Bryan won the Democratic nomination for the presidency after advocating “free silver” in a speech famously proclaiming “you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” He lost the general election to Republican William McKinley, who supported the gold standard.

Andrews had supported free silver in personal letters that were published in 1896 without his knowledge or permission. In July 1897, members of Brown’s governing “Corporation” expressed their concern that his views on what had become a highly controversial political issue were so upsetting to friends of the University that they were costing gifts and legacies.

Andrews resigned immediately, but Brown faculty, students, and alumni sent petitions on his behalf, as did other college presidents. Faculty warned the Corporation that to accept the resignation “would stamp this institution, in the eyes of the country, as one in which freedom of thought and expression is not permitted when it runs counter to the views generally accepted in the community or held by those from whom the University hopes to obtain financial support.”

Andrews noted that he had not “been loud, a declaimer, parading my views, ambitiously or otherwise” but insisted as a matter of academic principle that he could not surrender his freedom of speech. The Corporation asked him to withdraw his resignation, which he did.

Nevertheless, he left the following year for Chicago where, as superintendent of the Chicago Public Schools, he freed the schools from external political controls. Then, in 1900, he was appointed Chancellor of the University of Nebraska, which he transformed over the next eight years from a rapidly growing college into a genuine university.

Along with Wisconsin and Cornell, Nebraska was known at the turn of the 20th century as a haven of dissent. Andrews immediately reinforced that reputation.

In November 1900, Edward A. Ross, who was to become one of the founders of modern sociology, was fired by Stanford University for addressing issues of social injustice. The powerful Mrs. Stanford especially objected to his concern with Chinese railroad labor, the source of the Stanford family fortune. Andrews promptly hired Ross at Nebraska.

Other Stanford professors resigned in protest of the firing, including former Nebraska professor George Howard, a staunch supporter of civil liberties who had been hired by Stanford to found its history department and had in turn hired Ross. Andrews invited Howard back to Nebraska.

Andrews also rehired Harry Kirke Wolfe, the founding father of philosophy, psychology, and education at the University of Nebraska, who had been fired in 1897 for speaking out about falsification of student enrollment data. Wolfe returned in 1906 to found the department of educational psychology and later resumed his former position as chair of philosophy.

Poor health dogged Andrews throughout his life and finally forced him to retire at the end of 1908. After his death in 1917, the renowned college president and free speech advocate Alexander Meiklejohn, an 1893 graduate of Brown, eulogized him:

“Dear, gallant, stalwart, splendid Bennie Andrews... Oh, what a gallant fight he made, and what a hard one!”

At both Brown and UNL there is an Andrews Hall named for E. Benjamin Andrews. At Brown it is a residence hall; at UNL it houses the Department of English. Both students and academe were served well by his respect for intellectual freedom in higher education.

Information from The University of Nebraska

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Elisha Benjamin Andrews came to Nebraska after a national search for George MacLean’s successor, during which Charles Bessey served again as interim chancellor. Andrews, who was then serving as the superintendent of schools for the city of Chicago, had administered distinguished institutions before. He led Denison University in Ohio from 1875 to 1879, and his alma mater Brown University as its president from 1889 to 1898.

While the university had plateaued somewhat during MacLean’s tenure after its ascendance under James Canfield, it was still a formidable institution of national stature, and it grew under Andrews' leadership. In 1900, the year that he assumed the chancellorship, Nebraska’s enrollment stood at 2,200 students – a fairly large university for the time. Under his watch, the university grew to nearly 4,000 students.

An examination of the artifacts left by the student body in Canfield’s time, and again but perhaps to a lesser extent in Andrews’, reveals a remarkably talented, inquisitive and accomplished community of scholars driven to compete on the field and in the classroom with other great universities. They were determined to make the University of Nebraska equal to some of the widely revered institutions of the time, and in this Golden Age, largely accomplished the feat. It was during Andrews' time that the university's athletic teams, known variously as the fearsome "Bugeaters" and "Rattlesnake Boys," and the more staid and traditional "Old Gold Knights" in prior years, adopted a name suggested by a local sportswriter, Charlie "Cy" Sherman – the Cornhuskers.

Academically, a culture of debate rose at the university, in which the highest undergraduate academic calling was to be a member of the team led by Miller M. Fogg. Debate today remains a competitive high school activity sanctioned by the Nebraska School Activities Association. The Innocents Society was organized in 1903, in part as a counter to Theta Nu Epsilon, an antiauthoritarian "drinking fraternity." All-male, it was joined by the women's Black Masque a few years later. Both were dedicated to advancing both the individual and the institution, and membership was highly sought after.

Andrews sought and obtained funding from John D. Rockefeller for the university's first student activities building, matched at a 2:1 ratio with state funds after Andrews defeated the famously loquacious William Jennings Bryan in the court of public opinion. Bryan had objected to accepting the charity of a robber baron, but the Temple Building was erected anyway. All told, during his years at the helm, nine new buildings were constructed under Andrews' leadership.

Andrews re-ignited the restless ferment that had previously reached its zenith under Canfield. The university grew considerably during his tenure, and by the end of his chancellorship, the University of Nebraska was the nation's fifth-largest public institution.

According to the historian Robert Knoll in his "Prairie University," "Some persons think him the greatest chancellor the University of Nebraska has ever had and one of the noblest men who have passed this way."

Never in the best of health, Andrews spent the remainder of his life in Interlachen, Florida, where he died in 1917. His body was sent back to Denison University in Ohio, where he rests in the campus cemetery. At his funeral, Alexander Meiklejohn, the philosopher, free-speech crusader and university leader, eulogized him:

“Dear, gallant, stalwart, splendid Bennie Andrews. The zest of life was in him to the brim. He loved the things a man might be. Oh, what a gallant fight he made, and what a hard one! I cannot mourn that he is gone; I am too glad that he has been and is. He was a man. Yes, take him all in all, we shall not see his like again.”

Information from the University of Nebraska

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Andrews, Elisha Benjamin

Elisha Benjamin Andrews (1844-1917), eighth president of Brown University, was born in Hinsdale, New Hampshire, on January 10, 1844. His father and grandfather were Baptist ministers. He attended the Connecticut Literary Institute in Suffield, but left to enlist in the First Connecticut Heavy Artillery when the Civil War broke out. He rose to the rank of second lieutenant, and was severely wounded in a battle on the James River on August 24, 1864. He lost the sight of his left eye, which was replaced by a glass eye in 1884. He was mustered out of the army in October 1864. He then resumed his education at the Powers Institute in Bernardston and went on to Wesleyan Academy in Wilbraham, Massachusetts. He entered Brown in 1866 at the age of 22 and graduated in 1870. He had decided to became a minister, and served as a lay preacher and Sunday school teacher while in college. After graduation he returned to Suffield as principal of the academy for two years. He graduated from Newton Theological Institution in 1874, and was ordained in Beverly, Massachusetts, where he served as pastor for one year until he was called to the presidency of Denison University in 1875. At Denison he introduced elective courses and hired William Rainey Harper, a non-Baptist, to teach. A few years later he recommended that Harper leave Denison for the Baptist Union Theological Seminary of Chicago. Andrews left Denison in 1879, possibly because his liberal ideas irritated the trustees, although he remained a trustee until 1892. He became a professor of homiletics and pastoral theology at Newton, where he remained until 1882. While still at Newton in 1882, he also taught a philosophy course at Colby College taking the place of the president, who was ill. Andrews was appointed professor of history and political economy at Brown in 1882, but was allowed a year to study in Germany, while others continued the courses formerly taught by Professor J. Lewis Diman, who had died in 1881.

Arriving at Brown in September 1883, Andrews taught the history course and electives in Roman law, political economy, and international law. He wrote two historical textbooks, Brief Institutes of Our Constitutional History, English and American in 1886, a book written for use as a students’ syllabus of his lectures, and Brief Institutes of General History in 1887, an outline of history to the late nineteenth century. His later works, the four-volume set of History of the United States, published in 1894, and The Last Quarter-Century of the United States, in 1896, were written for popular consumption and were not up to his former standards.

He was a very effective teacher and was extremely popular with the students, and many were disappointed when he left in 1888 to teach at Cornell. He was not gone for long, however, as President Robinson resigned the next year, and Andrews was unanimously elected to replace him as president and professor of moral and intellectual philosophy.

Under his administration the University made great strides. Graduate study, just begun under Robinson, grew rapidly, undergraduate enrollment increased 140 per cent in eight years, and after some years of discussion, women were finally admitted, not at first to the University, but to examinations only. Andrews saw to it that arrangements were made for classes to prepare the women for the examinations. Brown professors were hired to teach them, and room was found for their classes in the University Grammar School. In the late afternoon when that building was dark, they moved to Andrews’ own office to continue their classes.

In his annual report for 1892 Andrews, after pointing out that the chemical laboratory, the botanical laboratory, Sayles Hall, and the dormitories were all outgrown, dared to present the greatest challenge yet. He wrote, “I cannot avoid the conviction that Brown University has reached a serious crisis in its history. It stands face to face with the question whether it will remain a College and nothing more or will rise and expand into a true University.... The expression, ‘a first-rate college which is a college only,’ I believe to be a contradiction in terms.” Citing the example of German universities and the need for research as well as teaching, he stated his objectives, “It is my belief ... that our alma mater will fail of her proper privilege and destiny unless, as rapidly as is consistent with healthy development, we promote her to the estate of a true University.” He called for raising a million dollars within a year, and two million more in ten years to found fellowships for advanced students, increase faculty salaries and establish new professorships, fund the library, support a school of applied science, and equip a Women’s College.

President Keeney said of him, “Andrews succeeded at the center and failed around the edges. He brought Brown to a height that it had never previously achieved; he assembled the best Faculty and student body that had ever been seen here. ... As President of Brown he was a great and tragic figure; He saw what had to be done, did it in part, and yet could not find the means to pay for it.”

The opinion of some Corporation members that the means might be forthcoming were it not for the political views of the president led to what came to be known as “The Andrews Controversy.” Andrews believed in international bimetallism and had expressed his views before and after becoming president. In the summer of 1896 a few of his personal letters, which were published, indicated that he had adopted the position that the United States should begin the free coinage of silver at the ratio of sixteen ounces of silver to one ounce of gold, without waiting for the cooperation of other countries. When this issue became paramount in the presidential election campaign of 1896, Andrews was far away in Europe, but was being freely quoted to the dismay of Corporation members who felt that his views were adversely affecting the prospects of the University. At the Corporation meeting in June 1897 it was resolved that a committee be appointed “to confer with the president in regard to the interests of the University.” In July the meeting was held, and the committee presented, at Andrews’ request, a written statement of the concerns of several members of the Corporation, “They signified a wish for a change in only one particular, having reference to his views upon a question which constituted a leading issue in the recent Presidential election and which is still predominant in National politics ... They considered that the views of the President, as made public by him from time to time ... were so contrary to the views generally held by the friends of the University that the University had already lost gifts and legacies which would otherwise have come or been assured to it, and that without a change it would in the future fail to receive the pecuniary support which is requisite to enable it to prosecute with success the grand work on which it has entered.” They did not require a renunciation of his views as long as he did not promulgate them. Andrews resigned the next day, stating that he could not surrender his right to freedom of speech. The case attracted much attention and was discussed throughout the country. At stake was either an institution’s right to restrain its head from actions not in its interest, or the whole issue of academic freedom.

In the midst of the controversy in the summer of 1897, Andrews had also accepted the offer received from John Brisben Walker, editor of Cosmopolitan Magazine, of the presidency of his proposed “Cosmopolitan University,” a tuition-free correspondence school for the educational benefit of the public. Andrews apparently intended to undertake this new project and still remain at Brown. Ill and distressed by the turmoil about him, he spent three weeks in August confined to a sanitarium in Wethersfield, Connecticut.

Meanwhile, an open letter to the Corporation by twenty-four Brown professors urged that the resignation not be accepted lest the reaction “would stamp this institution, in the eyes of the country, as one in which freedom of thought and expression is not permitted when it runs counter to the views generally accepted in the community or held by those from whom the University hopes to obtain financial support.&8221; Six hundred alumni signed petitions that requested the Corporation to “take action upon the resignation of President Andrews which will effectually refute the charge that reasonable liberty of utterance was, or ever is to be denied to any teacher of Brown University.” Of the 49 alumnae who owed their existence to Andrews, 46 sent a similar petition, and more than a hundred college presidents, professors, and public figures signed petitions requesting the Corporation not to accept the resignation. At a meeting of the Corporation on the first of September a statement by Andrews was presented, reiterating his belief in the unilateral free coinage of silver by the United States, but pointing out that his views had come to light only through the publication of personal letters written before the presidential campaign. He summed up his situation, “That ... I have been loud, a declaimer, parading my views, ambitiously or otherwise, I emphatically deny. Unfortunate I have been: indiscreet, I believe, I have not been.” The Corporation reconsidered and wrote to Andrews, “Having ... removed the misapprehension that your individual views on this question represent those of the Corporation and the University ... the Corporation, affirming its rightful authority to conserve ‘the interests of the University’ at all times ... cannot feel that the divergence of views between you and the members of the Corporation upon the ‘silver question’ and its effect upon the University is an adequate cause of separation between us, for the Corporation is profoundly appreciative of the great services you have rendered the University and of your sacrifice and love for it. It therefore renews its assurances of highest respect for you and expresses the confident hope that you will withdraw your resignation.” Andrews replied that he would do so as the Corporation’s action “entirely does away with the scruple which led to my resignation.”

The controversy over, the president returned to his duties, and the Boston Alumni Association started a movement to raise two million dollars to rescue the sagging resources of the University. Andrews, however, did not stay to partake of such improvements. He resigned in July 1898 to become superintendent of the Chicago public schools. After two years in Chicago he was named chancellor of the University of Nebraska, which position he held until his retirement because of ill health in 1908. During his administration in Nebraska, the enrollment had risen by fifty per cent, eight new buildings were built, and the legislative appropriation to the University nearly doubled. He died after an illness of several years on October 20, 1917 in Interlachen, Florida. Alexander Meiklejohn ’93 eulogized him:

“Dear, gallant, stalwart, splendid Bennie Andrews. The zest of life was in him to the brim. He loved the things a man might be. Oh, what a gallant fight he made, and what a hard one! I cannot mourn that he is gone; I am too glad that he has been and is. He was a man. Yes, take him all in all, we shall not see his like again.”

In his speech at the dedication of Andrews Hall, President Wriston said:

“Under Andrews, Brown ceased to be a small New England college and embraced the idea of a university. With him the ideal of scholarship, which must dominate a modern university, came to fruition. Graduate work was put on a solid basis. The thorny problem of the accommodation of women was solved in a manner both statesmanlike and tactful. The principles of academic freedom were dramatized and justified not only for Brown, but for all universities and colleges.... Is it any wonder that the largest building on the Pembroke campus is now named ‘Andrews Hall’?”

Information from Brown University/Encyclopedia Brunoniana by Martha Mitchell, Brown University Library.

Family Members

-

![]()

Emory Pearl Andrews

1830–1891

-

![]()

Emory Pearl Andrews

1830–1891

-

![]()

Martha Andrews Alden

1833–1904

-

![]()

Charles Bartlett Andrews

1834–1902

-

![]()

Erastus Ellsworth Andrews

1835–1897

-

![]()

John Lathrop Andrews

1837–1839

-

![]()

Thomas Dyer Andrews

1839–1856

-

![]()

Augustus Parker Cobb Andrews

1842–1866

-

![]()

Joseph Luther Mersenger Andrews

1845–1918

-

![]()

Arthur Eugene Nye Andrews

1849–1885

-

![]()

Flora Naomi Andrews

1850–1873