However, by the time Christian was 28 years old, he had married Katherina Margadant and had two daughters. There was little work to be had, and like many Europeans at this time, he decided to emigrate. He and his brothers were experienced lead miners and had heard that there was this type work to be had in Galena, Illinois, so he and two of his brothers decided to make the trip. By the time they reached the U.S., the type work they were familiar with was no longer available.

Christian’s two unmarried brothers decided to try their luck further west. Florian went to San Francisco and became wealthy with gold mining. Stefan went to Portland, OR. These two brothers went back to Switzerland after two years, Christian decided to move to Missouri where he found work and saved to bring his wife and children to the U.S. After Katherina came to America, they settled down and bought land in Lewis, Co., MO.

Christian enlisted in the Union Army in Co. F of the 43rd Regiment of Illinois Volunteers in the Civil War in 1861 and was discharged in St. Louis, MO for medical reasons in 1862. He became a naturalized citizen on September 16, 1868. He spent the rest of his life as a Missouri farmer. He died in 1908 while residing at the old Soldiers and Sailors Home in Quincy, IL.

******

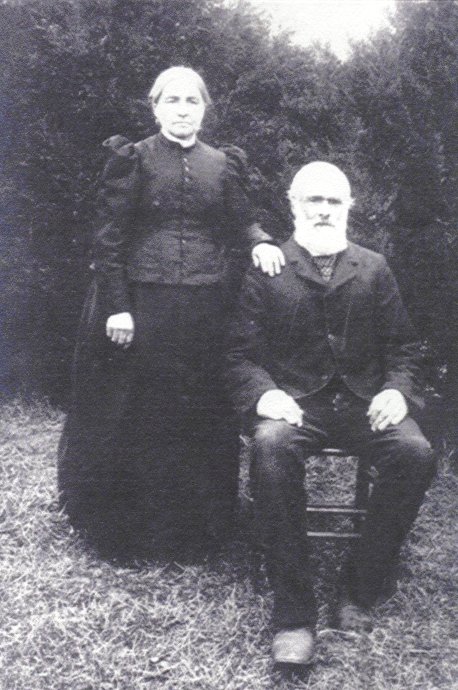

Christian was the son of Christian Gruber & Margareth Janett. He was born in Klosters, Switzerland & immigrated to the U. S. in 1856. He married Katherina Christina Margadant & they had 9 children. Christian served in the Union Army during the Civil War & he spent his final years in the Old Soldiers & Sailors Home in Quincy, IL.

Our Gruber Predecessors

Nestled on the northern foot of the eastern end of the Gotschengrat lies the village of Klosters, the last village in the Prättigau, a town renowned for its skiing, scenery, and the curative waters near-by. The beautiful Landquart River flows through the village, and the mighty Swiss Alps tower above. Mountain peak rises upon mountain peak. Between them lie the valleys with the alpine pastures. Behind them the high Engadine Valley with its mountain chains forms the boundary with Austria. Here beneath the majestic mountains, the Grubers, Margadants, Janetts, and Werlis, and their ancestors, the Ruedis, Maruggs, Gulers, Claßes, and Tönis had dwelt peacefully but with trepidation for centuries.

Though the landscape was weird and wonderful, nature was harsh and cruel. There were few families who had not experienced the loss of one or more members to the terrible epidemics which ravaged the population on a regular basis. Many entire families had been decimated or had lost all their belongings in the frequent, violent floods, conflagrations, landslides, and avalanches. On 10 August 1741, there was a frightful conflagration which destroyed 29 houses, 37 stables, and some granaries, along with many supplies. The awful floods of 1762 raged everywhere and destroyed 2 houses, 20 stables, 4 mills, 2 fulling machines, and 1 water saw. They even washed away ground and soil leaving pastures and fields mere rubbish heaps. They left behind totally impoverished families, but these families fought toughly and perseveringly against their poverty. Then on 17 June 1770, the mountain crashed down burying 17 people, 27 stables, 7 granaries, and many goods. Many families lost everything. In 1771, rocks came down in a tremendous landslide, destroying cottages and stables and killing almost all the animals. Lung plague raged through the cattle herds. All the cows had to be killed and buried where they lay. Jan Werli and Margretha Claßin, the great grandparents of our emigrant ancestress Katherina Margadant, lost everything in the mountain collapse in Monbiel in 1799, barely escaping with their lives. They began again and lost everything in a large fire the following year. They slaved and fought to build something up again for themselves and their children.

In addition to the natural disasters, widespread destruction was wrought by the constant warlike conditions created by the continual struggle for mastery between the Austrian and the French soldiers, and the Werlis watched impotently during the war years as their descendants again had everything taken away. There was frequent political unrest as the different factions jockeyed for dominance. Life had proceeded so for many generations, and the people had grown accustomed to its very tenuousness.

Klosters was a close-knit and congenial community, and each inhabitant of the village was vitally concerned for the welfare of the others. Every male, upon reaching his 14th birthday, was required to attend town meetings and to vote. The law also required that one male from each household take part in the road-breaking to open the passes whenever they became impassable with snow. The women congregated at the well in front of the church to do their laundry and to exchange gossip. They got together in the evenings to sew, spin, knit, sing together, and tell stories. The men sat and carved, smoked their pipes, and talked about the animals and the authorities. The people had a simple faith, and their belief in God and acceptance of His will shaped their lives.

At the beginning of the 19th Century at the time when Florian Gruber and his wife Anna Ruedi were raising their family, Klosters like many other mountain villages was shut off from the outside world. The inhabitants supported themselves through cattle trade and agriculture and planted peas, beans, barley, grain, hemp, flax, and potatoes. Drivers of pack animals brought additional grain over the passes from Southern Germany and salt from the Tyrol. Later they brought fruit, corn, chestnuts, and wine from the south. Most inhabitants were small farmers and tenants who also worked as jolters, woodsmen, raftsmen, saltpeter collectors, and resin or gentian distillers to maintain their large families. They lived and worked as their parents and grandparents had done from time immemorial.

When the snow covered everything, it drifted the people in the houses and left them peaceful. The men found employment in the forest. The women helped one another with the processing of hemp and flax, with spinning and weaving. Everyone had enough wood. When the potato harvest was good, even bread could be baked from these tubers. In November, the threshing and grinding was done. The canton of Graubünden had taken care that a few sacks of corn could be distributed in every district in time of need.

School began in November. Only some of the children attended school, and these were mostly boys. They read together loudly from the catechism or calendar, the Ten Commandments, or the songbook. They copied models, counted, and calculated. The small ones recited the alphabet in chorus forward and backward. The numbers of the multiplication tables buzzed through the room mixed with the pipe smoke of the teacher, the pungent, thick smoke from the old stove, the stuffy air of the room, and the smell of wet clothes, and the children's heads became full and heavy. By the dim light from a small window, the pupils scribbled and wrote on their slates or in their exercise books and pushed and bumped against their bench neighbors.

In May the farmers and their families, cats, dogs, and pigs moved to the spring pastures--small simple habitations on narrow terraces between the bottom of the valley and the Alps--and lived for some weeks while the animals grazed on the community pastures until the grass growth in the Alps could support the animals. In the summer, the cattle were entrusted to the alpine cheesemakers and herdsmen for 3 months. At the end of September, the cattle returned to the valley and fed in the autumn pastures until snowfall. Then the animals came into the stables with hay outside or above the houses and were fed until the hay ran out. Before Christmas, all the animals were in the stables next to the houses.

In August when the haymaking in the valley was finished, many farmers moved into the steep, alpine pastures for the mountain haying. These pastures were difficult to reach, so the cows could not be taken to them. The haymakers mowed and placed the spicy, strong mountain hay in haystacks, and in the first part of November, it was brought in a hay train of sleighs to the valley.

Klosters--the German word means monastery--was named for St. Jacob Monastery, which was founded between 1208 and 1222. The valley residents were Habsburg vassals under the supremacy of the Holy Roman Empire. In the Thirty Years War during the raids of the Austrians, out of 400 houses in Klosters, only 70 were undestroyed. In 1629, the Austrians again broke into the valley. The foreign soldiers brought war and ruin to the valley and also the plague. 540 persons died from June to December 1629. By late autumn 1633, more than 800 had died--70% of the population.

By 1803, far too many families fought for survival. Need, misery, and unemployment were everywhere. It would be better to emigrate than to be in permanent fear of landslides, fire, and avalanches, to live with empty stables and troughs, with hunger in the stomach, to live in a land where you no longer knew your way about. The people were bitter and discouraged with everything that had happened.

The Klosterser at this time seemed lazy, but they were discouraged, hopeless, and resigned to the forces of nature and conditions of life. They also had a pride in independence and an unconscious desire for distant lands, inherited from ancestors who went over the centuries as soldiers in foreign wars or to foreign countries as confectioners, coffeehouse owners, or trade and shop people. There was poverty in the villages. There were ragged, begging children; dilapidated houses; and dirty, unkempt old people. It was probably worse in the narrow villages standing near one another than in Klosters.

It happened that at this time a recruiter was looking for emigrants to go to the Crimean Peninsula on the Black Sea. The land was fertile and suited to agriculture, fruit growing, and cattle breeding. There was a colony already there, but they needed more people to settle the land. More than 100 people from all over Switzerland had already registered for the new emigrant group.

The women listened to their children sleep and waited while the men decided whether or not to emigrate. They could not sleep. They listened and waited for the steps of their husbands. The men had to discuss problems and trade, agree, and settle with one another. The women had nothing to do with that. The women had the work in the house, field, and garden; the managing of their children of all ages; and the care and welfare of the small ones. The husband had to support the family; he had to earn, to make political decisions, to maintain the domicile. Perhaps the wife was a silent advisor. The women did not think about crossing these limits. They needed their strength for everything else. The hard life sucked them dry and used them up. If the husband decided to emigrate, the wife had to pack the property, be silent, obey, and go with him. It didn't occur to the men to ask the women. The men must decide such weighty problems and decisions. The woman didn't understand men's affairs. She remained at home and waited on her husband, on the breadwinner and his commands. She waited patiently. She waited, listened to the breathing of the sleeping children, felt the new life in her body. God's will happened. God let everything happen for the best.

There was an old law that the property might not be cut into pieces upon the death of the father. One son undertook the farm, and the others looked out for other work and tried to make a living. Many young men had to abandon all thoughts of marriage, emigrate, drift into foreign war service, or work as farmhands or day laborers. Young men had always emigrated as mercenary soldiers, confectioners, shoemakers, merchants, wandering independents, and apprentices. Most later returned; oftentimes, it happened that they returned as rich men able to build splendid houses. However, it was not to be heard of that entire families with small children should emigrate.

In December 1803, many children became ill. They had fever and got diarrhea. Many children had died from dysentery and smallpox in 1802. In 1801, many had also died from smallpox.

On 27 March 1804, 21 families, including Grubers, Margadants, Werlis, Ruedis, and Maruggs, and comprised of 124 persons, emigrated from Klosters to the Crimea. The church bells rang to announce their departure. The bells were customarily rung to proclaim joy and sadness. They reminded the people; they called upon them. They called at fire and water troubles; they proclaimed war and peace.

The Crimean agent turned out to be a swindler and disappeared without a trace with the collected money. But though they were able to join a decent agent, the Russian authorities had issued new, stricter regulations, and only those who could produce 300 gulden could enter the country. Some decided to go home immediately. Others wanted to get the necessary money somehow and looked for work in the lowlands. During the entire month of July, families returned. Work could not be found in the lowlands. Beggars wandered from place to place. It would be better to go home than perish. Finally, all 21 families returned to Klosters.

In the industrial cantons, there was an indescribable famine in 1816. The people cooked hay and ate cats and dogs. They boiled bones soft or ground them into meal. Many people died, and everywhere there were dead people who had simply collapsed. The government offered grain and corn for people to buy. All of Europe was afflicted. The mountain people came through better than the city people. They at least had a little to eat and some money to buy food.

When Christian Gruber married Margreth Janett about 1817, she would probably have worn the traditional black wedding gown with a white veil, after having observed the customary one-year engagement period. Like all young couples, their hopes would have been high, but in 1817, there was a terrible winter with a lot of snow and frightful avalanches. A landslide came through the village, and the snow drifts surrounded the church up to the roof. The same avalanche dragged along 2 houses and 2 stables and killed 5 people and 9 animals. There were avalanches and great damage everywhere.

All of Switzerland, northern Italy, eastern France, and southern Germany were affected with a heavy increase in prices. From all these states, the conveyance of supplies to Switzerland was forbidden. They had to get food from Russia and Egypt. There was a lot of wheat in Russian Poland and in Egypt. Lentils were bought in bulk and transported to different cities in southern and western Europe. The people from Graubünden received the most from Genoa. Graubünden was able to get 100 measures of corn weekly, which was distributed to all the high courts or districts. In other cantons, many hundreds died of hunger. It was not as bad in Graubünden. Luckily, they had kept a lot of their cattle in the autumn because they were not worth much, so they could be slaughtered and sold. There were at least 200 people who had to live by the charity of the wealthy. Many poor families ate dead rabbits which had been killed by cows, goats, sheep, and dogs. Some farmers fed their cows with little fir branches. Many of the wealthy were very charitable.

At the time Christian and Margreth's 5th child Christian was born in 1828, the restless conditions in Switzerland had still not found balance, and the people were troubled and frightened. In 1834, huge cloudbursts caused frightful damage. Roads were destroyed, and the people were plunged into new debt for repair. Crushing taxes were collected for the casualties. Those who had already immigrated to America were beginning to write home to tell others to come with their families to America, where nothing was impossible, and many were leaving, but only a few people were going to America compared to the amount leaving for Russia and European cities at this time.

In 1836, Katherina's Uncle Peter Werli immigrated to the United States. By 1838, emigration was spoken of in the most remote farms and cottages. It brought unrest, hope, and fear. There were two major options--to immigrate to Russia or to immigrate to America. If you went to Russia, you could start earning immediately, and you could return even on foot from Russia. You couldn't do that from America. In addition, many ships never even arrived at their destinations. On the other hand, in America, you could acquire inexpensive land and be your own lord and master from the beginning. There was good land to buy at reasonable prices, and there was work to be had with good wages and a friendly reception in new Swiss settlements with planned schools and churches. In America, you could plant in huge, level fields instead of mountains. In Switzerland, with every thunderstorm, the earth washed down with the seeds. In Switzerland, you had to mow on the slopes, and you never knew whether you would be hurled to your death with the scythe still in your hand. The women would have it better if they could work on the flat ground and didn't have to clamber around on the ridges. No one would have to tie up the little children so they wouldn't tumble down like potatoes.

The emigration fever that had gripped entire villages in the lowlands had broken out in Klosters. Houses, stables, meadows, fields, and animals were sold or packed up. Loans were taken out. They saw in America a future without hopelessness. The authorities and vicars were flooded with emigration applications. New, stricter passport laws had been enacted. A recommendation of the authorities was necessary. A long time before departure, the intention had to be made public so the creditors could collect debts.

In the autumn of 1839, dysentery raged, especially among the children. Civil war was threatening Switzerland. There was potato rot for the 2nd year by 1843. Then there was a cholera epidemic. In the summer, one always feared the thunderstorms, wild brooks, and landslides connected with them. From the relatives in America came mostly encouraging and inviting reports, but many were full of homesickness and regret. Then in 1846, Katherina's Uncle Johannes immigrated to the United States. On 8 November 1847, civil war came to Switzerland. The lead and zinc mine in Klosters closed down in 1848, and wages for the past year could not be paid.

In spite of all the unrest, life continued in its never-ending cycle, and despite the unsettled conditions and uncertainty of life, Christian II married Katherina Christina Margadant on 7 July 1852. By 1856, even though he was now the father of two children, maybe for that very reason, Christian decided to try his luck in the New World, and he and his brother Andreas made plans to travel to America. Katherina and the two children would remain behind and wait for the summons to join him. Being from a mining community, some of the Klosterser had already found employment in the lead mine in Galena, IL, and it is probable that Christian and Andreas decided to join them there. However, one of our sources says they went instead to Wyaconda, MO, and then to Lewis Co., and another believes Christian first found work in New York City until he had saved enough money to bring his wife and family to the United States.

Though reluctant to leave loved ones behind, the brothers eagerly prepared for their journey as adventurous young men have always done. Most people first traveled to Le Havre, France, and thence by sailing ship to New York City, from which those bound for Illinois, Missouri, Iowa, and Wisconsin would travel further to New Orleans, LA, and on up the Mississippi River by steamboat. The trip across the ocean would take at least 2 months, and the price for passage was approximately 265 francs. It took a while to accumulate the necessary money and collect the items they had been instructed to bring with them. They had been told to bring enough warm underwear and waterproof clothing to last the entire trip, for clothing could not be washed in seawater, and the fresh water could be used only for cooking and drinking. They assembled the necessary papers—the passport, health certificate, and travel agreement. They packed their goods and chattels in wooden boxes and crates and tied them up firmly so nothing would be smashed.

Even though the law required that no captain leave port without 100 lbs. of biscuit and 100 lbs. of salt meat per person, each passenger was responsible for bringing much of his own food, and they had been advised beforehand as to how it should be packed so as best to preserve it. The foods to take included rusks; meal in barrels; bread, which would last 2 weeks; kettles or small cans of butter; eggs packed in meal, salt, or sand; dried, salted, or smoked meat, sausage, and bacon; rice, macaroni, and groats; potatoes; dried chestnuts and fruits; lemons and oranges packed in salt or sand; coffee; chocolate; seasonings; raisins and figs; grapes; almonds; sugar—water over 4 weeks old was potable only when sweetened—milk boiled with sugar and hermetically sealed; cheese; gelatin tablets; lentils; beans; and peas. They were required to bring 4 liters of wine vinegar per person in addition to whatever tea, wine, cider, beer, liqueurs, distilled water, or raspberry syrup they might require for their own use. Finally, the last box was nailed up, and the last little, home-woven sack was filled with dried fruit or home-dried meat or sausage, and they joined the long line of friends and neighbors who were also hoping for a better life. The dangerous and difficult travel weeks together would form a further bond between them, although the strain, the close gathering, and the exertion would lead to occasional tension and conflict.

At last, they were on their way. They would probably have traveled in April, as that was the best time of year to travel. Life aboard ship was far from pleasant. The emigration laws protected them only as long as they were in Switzerland. The suffering and danger began first on the high seas. The ships were overfilled, and on the ships, hundreds of people were crammed into a small space. The food spoiled in the heat and humidity, and on many ships, a terrible ship's fever was generated through bad air and food. There were some days with no wind when the ship didn't move for hours; then suddenly, a storm would arise, and the ship rocked to and fro like a plaything. Beds were soaked. The wind whistled through cracks and creakingly moved hanging objects. Everyone had to hold on so as not to be thrown around. They all knew there was danger of wrecking on reefs, running aground on sand dunes, lightning strikes, waterspouts, lack of water, famine, and illness, but they knew that they could as well be covered by an avalanche or landslide as wrecked on a sea reef. They knew, too, that floods on land are more dangerous than waterspouts and that lightning is more to be feared on land than at sea. They had done all they could to make provision against lack of food and water, and seasickness kills no one.

At the slave market in New Orleans, they saw people in chains being looked at by traders and handled and assessed like the cows at the markets in Klosters. They had probably never seen Negroes before.

Life aboard the steamship was another new experience. Often the Mississippi River seemed quiet and tame. Then unexpectedly, it was transformed into a tearing and bellowing giant with wild swirls and whirlpools and lurking, malicious sandbanks. Rock reefs hid beneath the surface. Its color often changed from a loamy, mustard yellow to a gloomy, dark brown. In the first weeks, they suffered from the muggy heat, the heavy, sticky air, and the horrible plague of gnats and flies, whole clouds of them. They saw unusual animals on land, in the water, and in the air. There were treacherous trees growing in the water with only their tops exposed, as well as uprooted trees, which were just as malicious. They rarely saw Indians.

There were hundreds of steamboats on the river, and some of them occasionally collided with oncoming, heavily laden vehicles. Some daredevil captains engaged in notorious, nonsensical boat races with the reckless captains of other steamers, whose overheated kettles sometimes exploded and set the ship afire.

The enormous paddlewheel turned untiringly and unceasingly. From the chimney rose black smoke, and the captain steered carefully past the dangerous obstacles. Often despite all caution, the ship settled on a sandbar. Sometimes, they had to dock to load food and firewood. The crew and the persons in 2nd class had to help with that. At Keokuk, IA, they crossed the rapids in an old-time barge and were cordelled up the shore by horses as far as Montrose, IA, from where they continued on upriver to Galena, IL. The trip up the Mississippi took an entire month.

At last they had reached their destination! But to their dismay, they found that the lead mine had closed down, and there was no work to be had. Discouraged but still not lacking in confidence, they retraced their journey as far as northeastern Missouri, where some of their relatives had settled. There the farmers, who did not want to have black slaves, always needed good land workers. The land was especially suited to agricultural purposes and cattle breeding. Christian hired out as a farm laborer in Canton. That was how he and his brothers and sisters in Klosters had lived, but here there was at least hope to have something of his own eventually. He wanted to work and work and build a new life for his descendants.

Andreas wanted to go to California for gold, so he traveled alone to St. Louis and on down the Mississippi to New Orleans. California-bound ships left there on a daily basis. Andreas found work in the gold mines and sent home $250 with which his relatives bought a parcel of land in Selfranga. His brothers Stephan and Florian decided to join him and made the journey to America. Work in the gold mines was difficult and debilitating, and Andreas developed a bad cough and rheumatism, so he gave up goldmining and earned good money from other work. By 1864, Andreas and Stephan were living in Portland, OR, and Florian was in San Francisco, CA, and by 1869, all three of the unmarried brothers had returned to Switzerland. Florian and Stephan never married, but Andreas later married a widow and became the ancestor of the cousins who have been located and still reside in the beautiful, little village of Klosters.

In 1857, the summons came, and Katherina knew she would have to make the cruel journey alone with only the two little girls, aged 1 and 2, as her traveling companions. She also had strenuous preparations to make, but finally, the day arrived when she must leave behind forever her home and her dear ones. It was a relief to realize that her husband and uncles would be waiting at the end of the journey.

What a horror awaited this gentle woman and the small children aboard the ship. They went to the ship with their heavy, travel sacks in their hands, so they were all tired and exhausted when they finally arrived. They had to cross over to the ship on a weak, narrow board; then they had to stand around on deck while the boxes were brought on board and let down into the ship with long chains. When the boxes had all been loaded, the sailors threw down some miserable straw sacks, and they had to go down a wretched ladder into the dark, deep hole where the boxes and straw sacks had been thrown. There they had to lie down on the boxes and straw sacks as well as they could. The ship was overfilled, and the emigrants were packed in like herring, men, women, and children all together in mass confusion. Some had to sit on each other, others to squat, others to lie down. Some started to cry; others fled; still others said they were leaving, but by now, there was no way of exiting the ship. It had to be endured. There were no windows. At night, the air was bad, and by day, a draft came down through the hole where the ladder was. Frightful storms raged around the ship day after day. The food spoiled and ran out. Katherina must have known of the dangers of smallpox, cholera, and ship's fever, but which of us can even begin to imagine the helplessness and horror she must have felt when her own little Margreth, the 2 year old, sickened and died? It was hardly to be borne as the small child was wrenched from her arms and she must watch as the sailors let the little, loved one slide over a plank into the sea. The poor woman must have been so frightened and confused. Her granddaughter Bea Gruber would later recall how as a child she had been told by her grandmother that her baby had to be thrown overboard to keep the sharks from upsetting the boat and getting all the rest of the passengers. This must have been what she was told in order to get her to relinquish her child for the watery burial.

How grief-stricken Christian must have been when his family finally arrived and he learned that one dear, little member was lacking. But with their faith in God, they knew that life goes on and that their darling was in a better place, so they sadly continued on with their earthly journey. By 1861, things were not going well for Christian and Katherina. Two more children had joined their family, and they looked forward to the future with confidence. They hoped for the Homestead Act to come into effect in 1862. It would make the buying of land easier for the new settlers. If you were over 21, head of a family, and a citizen or intending to become one, you could get 160 acres of land when you had lived on the land for 5 years and built a house. If you had not lived there for 5 years, the land was $1.25 per acre.

In the meantime civil war had broken out between the northern and the southern states. These were bad times in America, especially for the new settlers. The Grubers needed money for their small farm and the bunch of children, who were constantly growing. Everything cost 4 times as much as before. They had no money to send a substitute to the war, and as a married man, he could receive $20 per month, and in addition, the county would take care of his family, so in 1861, Christian enlisted in Co. F, 43rd Regiment of Illinois Volunteers. At home in Klosters, rumors were rampant that he was not getting along with his wife and that he simply wanted to get away from his family and be free to do as he wanted. But this good man had many defenders who knew him far better than those who talked against him. Christian developed varicose veins and was discharged from the Army in St. Louis for medical reasons in 1862, and returned to his family.

After returning home from the war, Christian settled down on the small farm he had finally be able to acquire, and he and Katherina continued to increase the population of their adopted country. They would eventually become the parents of five sons and two daughters in addition to little Margreth who had perished and been buried at sea and another daughter named Margreth who also died at an early age. On 16 September 1868, Christian became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

Christian and Katherina grew old and weathered many storms together, but some memories they never lost. The memories that hurt were the beloved mountains, the smell of the meadows, the forest, the sound of the cowbells and scythes. Memories which still filled them with horror were rushing or waiting crowds of people between mountains of luggage; the ship; the throngs of people at the ports; nothing but water and sky day after day and week after week; storms so bad that it seemed that each moment would be your last; the grief at watching as your own little child was simply sewn up in a sack and thrown into the sea; the arrival in New York amidst thousands of other immigrants. They felt again the rocking of the ship and heard calls, laughs, cries, and children's screams. They saw again the over-filled ship's compartment without windows and smelled the appalling stench of vomit, urine, and sweat. And always and always, the haunting memory of the dear, little, dead Margreth.

In later life, Christian applied for and received a small veterans pension, and after his life partner of more than fifty years went to her final rest, he moved into the Old Soldiers and Sailors Home in Quincy, IL, where he lived out the remaining years of his life.

Although Andrew Lewis Gruber was not the eldest son, he came into possession of the family farm, and he and his wife Tresa Ellen Tuley lived and farmed there and raised their four children, and the land has continued in the family up to the present time.

I am indebted to Ursula Lehmann-Gugolz of Berne, Switzerland, for much of the information in this chapter.

However, by the time Christian was 28 years old, he had married Katherina Margadant and had two daughters. There was little work to be had, and like many Europeans at this time, he decided to emigrate. He and his brothers were experienced lead miners and had heard that there was this type work to be had in Galena, Illinois, so he and two of his brothers decided to make the trip. By the time they reached the U.S., the type work they were familiar with was no longer available.

Christian’s two unmarried brothers decided to try their luck further west. Florian went to San Francisco and became wealthy with gold mining. Stefan went to Portland, OR. These two brothers went back to Switzerland after two years, Christian decided to move to Missouri where he found work and saved to bring his wife and children to the U.S. After Katherina came to America, they settled down and bought land in Lewis, Co., MO.

Christian enlisted in the Union Army in Co. F of the 43rd Regiment of Illinois Volunteers in the Civil War in 1861 and was discharged in St. Louis, MO for medical reasons in 1862. He became a naturalized citizen on September 16, 1868. He spent the rest of his life as a Missouri farmer. He died in 1908 while residing at the old Soldiers and Sailors Home in Quincy, IL.

******

Christian was the son of Christian Gruber & Margareth Janett. He was born in Klosters, Switzerland & immigrated to the U. S. in 1856. He married Katherina Christina Margadant & they had 9 children. Christian served in the Union Army during the Civil War & he spent his final years in the Old Soldiers & Sailors Home in Quincy, IL.

Our Gruber Predecessors

Nestled on the northern foot of the eastern end of the Gotschengrat lies the village of Klosters, the last village in the Prättigau, a town renowned for its skiing, scenery, and the curative waters near-by. The beautiful Landquart River flows through the village, and the mighty Swiss Alps tower above. Mountain peak rises upon mountain peak. Between them lie the valleys with the alpine pastures. Behind them the high Engadine Valley with its mountain chains forms the boundary with Austria. Here beneath the majestic mountains, the Grubers, Margadants, Janetts, and Werlis, and their ancestors, the Ruedis, Maruggs, Gulers, Claßes, and Tönis had dwelt peacefully but with trepidation for centuries.

Though the landscape was weird and wonderful, nature was harsh and cruel. There were few families who had not experienced the loss of one or more members to the terrible epidemics which ravaged the population on a regular basis. Many entire families had been decimated or had lost all their belongings in the frequent, violent floods, conflagrations, landslides, and avalanches. On 10 August 1741, there was a frightful conflagration which destroyed 29 houses, 37 stables, and some granaries, along with many supplies. The awful floods of 1762 raged everywhere and destroyed 2 houses, 20 stables, 4 mills, 2 fulling machines, and 1 water saw. They even washed away ground and soil leaving pastures and fields mere rubbish heaps. They left behind totally impoverished families, but these families fought toughly and perseveringly against their poverty. Then on 17 June 1770, the mountain crashed down burying 17 people, 27 stables, 7 granaries, and many goods. Many families lost everything. In 1771, rocks came down in a tremendous landslide, destroying cottages and stables and killing almost all the animals. Lung plague raged through the cattle herds. All the cows had to be killed and buried where they lay. Jan Werli and Margretha Claßin, the great grandparents of our emigrant ancestress Katherina Margadant, lost everything in the mountain collapse in Monbiel in 1799, barely escaping with their lives. They began again and lost everything in a large fire the following year. They slaved and fought to build something up again for themselves and their children.

In addition to the natural disasters, widespread destruction was wrought by the constant warlike conditions created by the continual struggle for mastery between the Austrian and the French soldiers, and the Werlis watched impotently during the war years as their descendants again had everything taken away. There was frequent political unrest as the different factions jockeyed for dominance. Life had proceeded so for many generations, and the people had grown accustomed to its very tenuousness.

Klosters was a close-knit and congenial community, and each inhabitant of the village was vitally concerned for the welfare of the others. Every male, upon reaching his 14th birthday, was required to attend town meetings and to vote. The law also required that one male from each household take part in the road-breaking to open the passes whenever they became impassable with snow. The women congregated at the well in front of the church to do their laundry and to exchange gossip. They got together in the evenings to sew, spin, knit, sing together, and tell stories. The men sat and carved, smoked their pipes, and talked about the animals and the authorities. The people had a simple faith, and their belief in God and acceptance of His will shaped their lives.

At the beginning of the 19th Century at the time when Florian Gruber and his wife Anna Ruedi were raising their family, Klosters like many other mountain villages was shut off from the outside world. The inhabitants supported themselves through cattle trade and agriculture and planted peas, beans, barley, grain, hemp, flax, and potatoes. Drivers of pack animals brought additional grain over the passes from Southern Germany and salt from the Tyrol. Later they brought fruit, corn, chestnuts, and wine from the south. Most inhabitants were small farmers and tenants who also worked as jolters, woodsmen, raftsmen, saltpeter collectors, and resin or gentian distillers to maintain their large families. They lived and worked as their parents and grandparents had done from time immemorial.

When the snow covered everything, it drifted the people in the houses and left them peaceful. The men found employment in the forest. The women helped one another with the processing of hemp and flax, with spinning and weaving. Everyone had enough wood. When the potato harvest was good, even bread could be baked from these tubers. In November, the threshing and grinding was done. The canton of Graubünden had taken care that a few sacks of corn could be distributed in every district in time of need.

School began in November. Only some of the children attended school, and these were mostly boys. They read together loudly from the catechism or calendar, the Ten Commandments, or the songbook. They copied models, counted, and calculated. The small ones recited the alphabet in chorus forward and backward. The numbers of the multiplication tables buzzed through the room mixed with the pipe smoke of the teacher, the pungent, thick smoke from the old stove, the stuffy air of the room, and the smell of wet clothes, and the children's heads became full and heavy. By the dim light from a small window, the pupils scribbled and wrote on their slates or in their exercise books and pushed and bumped against their bench neighbors.

In May the farmers and their families, cats, dogs, and pigs moved to the spring pastures--small simple habitations on narrow terraces between the bottom of the valley and the Alps--and lived for some weeks while the animals grazed on the community pastures until the grass growth in the Alps could support the animals. In the summer, the cattle were entrusted to the alpine cheesemakers and herdsmen for 3 months. At the end of September, the cattle returned to the valley and fed in the autumn pastures until snowfall. Then the animals came into the stables with hay outside or above the houses and were fed until the hay ran out. Before Christmas, all the animals were in the stables next to the houses.

In August when the haymaking in the valley was finished, many farmers moved into the steep, alpine pastures for the mountain haying. These pastures were difficult to reach, so the cows could not be taken to them. The haymakers mowed and placed the spicy, strong mountain hay in haystacks, and in the first part of November, it was brought in a hay train of sleighs to the valley.

Klosters--the German word means monastery--was named for St. Jacob Monastery, which was founded between 1208 and 1222. The valley residents were Habsburg vassals under the supremacy of the Holy Roman Empire. In the Thirty Years War during the raids of the Austrians, out of 400 houses in Klosters, only 70 were undestroyed. In 1629, the Austrians again broke into the valley. The foreign soldiers brought war and ruin to the valley and also the plague. 540 persons died from June to December 1629. By late autumn 1633, more than 800 had died--70% of the population.

By 1803, far too many families fought for survival. Need, misery, and unemployment were everywhere. It would be better to emigrate than to be in permanent fear of landslides, fire, and avalanches, to live with empty stables and troughs, with hunger in the stomach, to live in a land where you no longer knew your way about. The people were bitter and discouraged with everything that had happened.

The Klosterser at this time seemed lazy, but they were discouraged, hopeless, and resigned to the forces of nature and conditions of life. They also had a pride in independence and an unconscious desire for distant lands, inherited from ancestors who went over the centuries as soldiers in foreign wars or to foreign countries as confectioners, coffeehouse owners, or trade and shop people. There was poverty in the villages. There were ragged, begging children; dilapidated houses; and dirty, unkempt old people. It was probably worse in the narrow villages standing near one another than in Klosters.

It happened that at this time a recruiter was looking for emigrants to go to the Crimean Peninsula on the Black Sea. The land was fertile and suited to agriculture, fruit growing, and cattle breeding. There was a colony already there, but they needed more people to settle the land. More than 100 people from all over Switzerland had already registered for the new emigrant group.

The women listened to their children sleep and waited while the men decided whether or not to emigrate. They could not sleep. They listened and waited for the steps of their husbands. The men had to discuss problems and trade, agree, and settle with one another. The women had nothing to do with that. The women had the work in the house, field, and garden; the managing of their children of all ages; and the care and welfare of the small ones. The husband had to support the family; he had to earn, to make political decisions, to maintain the domicile. Perhaps the wife was a silent advisor. The women did not think about crossing these limits. They needed their strength for everything else. The hard life sucked them dry and used them up. If the husband decided to emigrate, the wife had to pack the property, be silent, obey, and go with him. It didn't occur to the men to ask the women. The men must decide such weighty problems and decisions. The woman didn't understand men's affairs. She remained at home and waited on her husband, on the breadwinner and his commands. She waited patiently. She waited, listened to the breathing of the sleeping children, felt the new life in her body. God's will happened. God let everything happen for the best.

There was an old law that the property might not be cut into pieces upon the death of the father. One son undertook the farm, and the others looked out for other work and tried to make a living. Many young men had to abandon all thoughts of marriage, emigrate, drift into foreign war service, or work as farmhands or day laborers. Young men had always emigrated as mercenary soldiers, confectioners, shoemakers, merchants, wandering independents, and apprentices. Most later returned; oftentimes, it happened that they returned as rich men able to build splendid houses. However, it was not to be heard of that entire families with small children should emigrate.

In December 1803, many children became ill. They had fever and got diarrhea. Many children had died from dysentery and smallpox in 1802. In 1801, many had also died from smallpox.

On 27 March 1804, 21 families, including Grubers, Margadants, Werlis, Ruedis, and Maruggs, and comprised of 124 persons, emigrated from Klosters to the Crimea. The church bells rang to announce their departure. The bells were customarily rung to proclaim joy and sadness. They reminded the people; they called upon them. They called at fire and water troubles; they proclaimed war and peace.

The Crimean agent turned out to be a swindler and disappeared without a trace with the collected money. But though they were able to join a decent agent, the Russian authorities had issued new, stricter regulations, and only those who could produce 300 gulden could enter the country. Some decided to go home immediately. Others wanted to get the necessary money somehow and looked for work in the lowlands. During the entire month of July, families returned. Work could not be found in the lowlands. Beggars wandered from place to place. It would be better to go home than perish. Finally, all 21 families returned to Klosters.

In the industrial cantons, there was an indescribable famine in 1816. The people cooked hay and ate cats and dogs. They boiled bones soft or ground them into meal. Many people died, and everywhere there were dead people who had simply collapsed. The government offered grain and corn for people to buy. All of Europe was afflicted. The mountain people came through better than the city people. They at least had a little to eat and some money to buy food.

When Christian Gruber married Margreth Janett about 1817, she would probably have worn the traditional black wedding gown with a white veil, after having observed the customary one-year engagement period. Like all young couples, their hopes would have been high, but in 1817, there was a terrible winter with a lot of snow and frightful avalanches. A landslide came through the village, and the snow drifts surrounded the church up to the roof. The same avalanche dragged along 2 houses and 2 stables and killed 5 people and 9 animals. There were avalanches and great damage everywhere.

All of Switzerland, northern Italy, eastern France, and southern Germany were affected with a heavy increase in prices. From all these states, the conveyance of supplies to Switzerland was forbidden. They had to get food from Russia and Egypt. There was a lot of wheat in Russian Poland and in Egypt. Lentils were bought in bulk and transported to different cities in southern and western Europe. The people from Graubünden received the most from Genoa. Graubünden was able to get 100 measures of corn weekly, which was distributed to all the high courts or districts. In other cantons, many hundreds died of hunger. It was not as bad in Graubünden. Luckily, they had kept a lot of their cattle in the autumn because they were not worth much, so they could be slaughtered and sold. There were at least 200 people who had to live by the charity of the wealthy. Many poor families ate dead rabbits which had been killed by cows, goats, sheep, and dogs. Some farmers fed their cows with little fir branches. Many of the wealthy were very charitable.

At the time Christian and Margreth's 5th child Christian was born in 1828, the restless conditions in Switzerland had still not found balance, and the people were troubled and frightened. In 1834, huge cloudbursts caused frightful damage. Roads were destroyed, and the people were plunged into new debt for repair. Crushing taxes were collected for the casualties. Those who had already immigrated to America were beginning to write home to tell others to come with their families to America, where nothing was impossible, and many were leaving, but only a few people were going to America compared to the amount leaving for Russia and European cities at this time.

In 1836, Katherina's Uncle Peter Werli immigrated to the United States. By 1838, emigration was spoken of in the most remote farms and cottages. It brought unrest, hope, and fear. There were two major options--to immigrate to Russia or to immigrate to America. If you went to Russia, you could start earning immediately, and you could return even on foot from Russia. You couldn't do that from America. In addition, many ships never even arrived at their destinations. On the other hand, in America, you could acquire inexpensive land and be your own lord and master from the beginning. There was good land to buy at reasonable prices, and there was work to be had with good wages and a friendly reception in new Swiss settlements with planned schools and churches. In America, you could plant in huge, level fields instead of mountains. In Switzerland, with every thunderstorm, the earth washed down with the seeds. In Switzerland, you had to mow on the slopes, and you never knew whether you would be hurled to your death with the scythe still in your hand. The women would have it better if they could work on the flat ground and didn't have to clamber around on the ridges. No one would have to tie up the little children so they wouldn't tumble down like potatoes.

The emigration fever that had gripped entire villages in the lowlands had broken out in Klosters. Houses, stables, meadows, fields, and animals were sold or packed up. Loans were taken out. They saw in America a future without hopelessness. The authorities and vicars were flooded with emigration applications. New, stricter passport laws had been enacted. A recommendation of the authorities was necessary. A long time before departure, the intention had to be made public so the creditors could collect debts.

In the autumn of 1839, dysentery raged, especially among the children. Civil war was threatening Switzerland. There was potato rot for the 2nd year by 1843. Then there was a cholera epidemic. In the summer, one always feared the thunderstorms, wild brooks, and landslides connected with them. From the relatives in America came mostly encouraging and inviting reports, but many were full of homesickness and regret. Then in 1846, Katherina's Uncle Johannes immigrated to the United States. On 8 November 1847, civil war came to Switzerland. The lead and zinc mine in Klosters closed down in 1848, and wages for the past year could not be paid.

In spite of all the unrest, life continued in its never-ending cycle, and despite the unsettled conditions and uncertainty of life, Christian II married Katherina Christina Margadant on 7 July 1852. By 1856, even though he was now the father of two children, maybe for that very reason, Christian decided to try his luck in the New World, and he and his brother Andreas made plans to travel to America. Katherina and the two children would remain behind and wait for the summons to join him. Being from a mining community, some of the Klosterser had already found employment in the lead mine in Galena, IL, and it is probable that Christian and Andreas decided to join them there. However, one of our sources says they went instead to Wyaconda, MO, and then to Lewis Co., and another believes Christian first found work in New York City until he had saved enough money to bring his wife and family to the United States.

Though reluctant to leave loved ones behind, the brothers eagerly prepared for their journey as adventurous young men have always done. Most people first traveled to Le Havre, France, and thence by sailing ship to New York City, from which those bound for Illinois, Missouri, Iowa, and Wisconsin would travel further to New Orleans, LA, and on up the Mississippi River by steamboat. The trip across the ocean would take at least 2 months, and the price for passage was approximately 265 francs. It took a while to accumulate the necessary money and collect the items they had been instructed to bring with them. They had been told to bring enough warm underwear and waterproof clothing to last the entire trip, for clothing could not be washed in seawater, and the fresh water could be used only for cooking and drinking. They assembled the necessary papers—the passport, health certificate, and travel agreement. They packed their goods and chattels in wooden boxes and crates and tied them up firmly so nothing would be smashed.

Even though the law required that no captain leave port without 100 lbs. of biscuit and 100 lbs. of salt meat per person, each passenger was responsible for bringing much of his own food, and they had been advised beforehand as to how it should be packed so as best to preserve it. The foods to take included rusks; meal in barrels; bread, which would last 2 weeks; kettles or small cans of butter; eggs packed in meal, salt, or sand; dried, salted, or smoked meat, sausage, and bacon; rice, macaroni, and groats; potatoes; dried chestnuts and fruits; lemons and oranges packed in salt or sand; coffee; chocolate; seasonings; raisins and figs; grapes; almonds; sugar—water over 4 weeks old was potable only when sweetened—milk boiled with sugar and hermetically sealed; cheese; gelatin tablets; lentils; beans; and peas. They were required to bring 4 liters of wine vinegar per person in addition to whatever tea, wine, cider, beer, liqueurs, distilled water, or raspberry syrup they might require for their own use. Finally, the last box was nailed up, and the last little, home-woven sack was filled with dried fruit or home-dried meat or sausage, and they joined the long line of friends and neighbors who were also hoping for a better life. The dangerous and difficult travel weeks together would form a further bond between them, although the strain, the close gathering, and the exertion would lead to occasional tension and conflict.

At last, they were on their way. They would probably have traveled in April, as that was the best time of year to travel. Life aboard ship was far from pleasant. The emigration laws protected them only as long as they were in Switzerland. The suffering and danger began first on the high seas. The ships were overfilled, and on the ships, hundreds of people were crammed into a small space. The food spoiled in the heat and humidity, and on many ships, a terrible ship's fever was generated through bad air and food. There were some days with no wind when the ship didn't move for hours; then suddenly, a storm would arise, and the ship rocked to and fro like a plaything. Beds were soaked. The wind whistled through cracks and creakingly moved hanging objects. Everyone had to hold on so as not to be thrown around. They all knew there was danger of wrecking on reefs, running aground on sand dunes, lightning strikes, waterspouts, lack of water, famine, and illness, but they knew that they could as well be covered by an avalanche or landslide as wrecked on a sea reef. They knew, too, that floods on land are more dangerous than waterspouts and that lightning is more to be feared on land than at sea. They had done all they could to make provision against lack of food and water, and seasickness kills no one.

At the slave market in New Orleans, they saw people in chains being looked at by traders and handled and assessed like the cows at the markets in Klosters. They had probably never seen Negroes before.

Life aboard the steamship was another new experience. Often the Mississippi River seemed quiet and tame. Then unexpectedly, it was transformed into a tearing and bellowing giant with wild swirls and whirlpools and lurking, malicious sandbanks. Rock reefs hid beneath the surface. Its color often changed from a loamy, mustard yellow to a gloomy, dark brown. In the first weeks, they suffered from the muggy heat, the heavy, sticky air, and the horrible plague of gnats and flies, whole clouds of them. They saw unusual animals on land, in the water, and in the air. There were treacherous trees growing in the water with only their tops exposed, as well as uprooted trees, which were just as malicious. They rarely saw Indians.

There were hundreds of steamboats on the river, and some of them occasionally collided with oncoming, heavily laden vehicles. Some daredevil captains engaged in notorious, nonsensical boat races with the reckless captains of other steamers, whose overheated kettles sometimes exploded and set the ship afire.

The enormous paddlewheel turned untiringly and unceasingly. From the chimney rose black smoke, and the captain steered carefully past the dangerous obstacles. Often despite all caution, the ship settled on a sandbar. Sometimes, they had to dock to load food and firewood. The crew and the persons in 2nd class had to help with that. At Keokuk, IA, they crossed the rapids in an old-time barge and were cordelled up the shore by horses as far as Montrose, IA, from where they continued on upriver to Galena, IL. The trip up the Mississippi took an entire month.

At last they had reached their destination! But to their dismay, they found that the lead mine had closed down, and there was no work to be had. Discouraged but still not lacking in confidence, they retraced their journey as far as northeastern Missouri, where some of their relatives had settled. There the farmers, who did not want to have black slaves, always needed good land workers. The land was especially suited to agricultural purposes and cattle breeding. Christian hired out as a farm laborer in Canton. That was how he and his brothers and sisters in Klosters had lived, but here there was at least hope to have something of his own eventually. He wanted to work and work and build a new life for his descendants.

Andreas wanted to go to California for gold, so he traveled alone to St. Louis and on down the Mississippi to New Orleans. California-bound ships left there on a daily basis. Andreas found work in the gold mines and sent home $250 with which his relatives bought a parcel of land in Selfranga. His brothers Stephan and Florian decided to join him and made the journey to America. Work in the gold mines was difficult and debilitating, and Andreas developed a bad cough and rheumatism, so he gave up goldmining and earned good money from other work. By 1864, Andreas and Stephan were living in Portland, OR, and Florian was in San Francisco, CA, and by 1869, all three of the unmarried brothers had returned to Switzerland. Florian and Stephan never married, but Andreas later married a widow and became the ancestor of the cousins who have been located and still reside in the beautiful, little village of Klosters.

In 1857, the summons came, and Katherina knew she would have to make the cruel journey alone with only the two little girls, aged 1 and 2, as her traveling companions. She also had strenuous preparations to make, but finally, the day arrived when she must leave behind forever her home and her dear ones. It was a relief to realize that her husband and uncles would be waiting at the end of the journey.

What a horror awaited this gentle woman and the small children aboard the ship. They went to the ship with their heavy, travel sacks in their hands, so they were all tired and exhausted when they finally arrived. They had to cross over to the ship on a weak, narrow board; then they had to stand around on deck while the boxes were brought on board and let down into the ship with long chains. When the boxes had all been loaded, the sailors threw down some miserable straw sacks, and they had to go down a wretched ladder into the dark, deep hole where the boxes and straw sacks had been thrown. There they had to lie down on the boxes and straw sacks as well as they could. The ship was overfilled, and the emigrants were packed in like herring, men, women, and children all together in mass confusion. Some had to sit on each other, others to squat, others to lie down. Some started to cry; others fled; still others said they were leaving, but by now, there was no way of exiting the ship. It had to be endured. There were no windows. At night, the air was bad, and by day, a draft came down through the hole where the ladder was. Frightful storms raged around the ship day after day. The food spoiled and ran out. Katherina must have known of the dangers of smallpox, cholera, and ship's fever, but which of us can even begin to imagine the helplessness and horror she must have felt when her own little Margreth, the 2 year old, sickened and died? It was hardly to be borne as the small child was wrenched from her arms and she must watch as the sailors let the little, loved one slide over a plank into the sea. The poor woman must have been so frightened and confused. Her granddaughter Bea Gruber would later recall how as a child she had been told by her grandmother that her baby had to be thrown overboard to keep the sharks from upsetting the boat and getting all the rest of the passengers. This must have been what she was told in order to get her to relinquish her child for the watery burial.

How grief-stricken Christian must have been when his family finally arrived and he learned that one dear, little member was lacking. But with their faith in God, they knew that life goes on and that their darling was in a better place, so they sadly continued on with their earthly journey. By 1861, things were not going well for Christian and Katherina. Two more children had joined their family, and they looked forward to the future with confidence. They hoped for the Homestead Act to come into effect in 1862. It would make the buying of land easier for the new settlers. If you were over 21, head of a family, and a citizen or intending to become one, you could get 160 acres of land when you had lived on the land for 5 years and built a house. If you had not lived there for 5 years, the land was $1.25 per acre.

In the meantime civil war had broken out between the northern and the southern states. These were bad times in America, especially for the new settlers. The Grubers needed money for their small farm and the bunch of children, who were constantly growing. Everything cost 4 times as much as before. They had no money to send a substitute to the war, and as a married man, he could receive $20 per month, and in addition, the county would take care of his family, so in 1861, Christian enlisted in Co. F, 43rd Regiment of Illinois Volunteers. At home in Klosters, rumors were rampant that he was not getting along with his wife and that he simply wanted to get away from his family and be free to do as he wanted. But this good man had many defenders who knew him far better than those who talked against him. Christian developed varicose veins and was discharged from the Army in St. Louis for medical reasons in 1862, and returned to his family.

After returning home from the war, Christian settled down on the small farm he had finally be able to acquire, and he and Katherina continued to increase the population of their adopted country. They would eventually become the parents of five sons and two daughters in addition to little Margreth who had perished and been buried at sea and another daughter named Margreth who also died at an early age. On 16 September 1868, Christian became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

Christian and Katherina grew old and weathered many storms together, but some memories they never lost. The memories that hurt were the beloved mountains, the smell of the meadows, the forest, the sound of the cowbells and scythes. Memories which still filled them with horror were rushing or waiting crowds of people between mountains of luggage; the ship; the throngs of people at the ports; nothing but water and sky day after day and week after week; storms so bad that it seemed that each moment would be your last; the grief at watching as your own little child was simply sewn up in a sack and thrown into the sea; the arrival in New York amidst thousands of other immigrants. They felt again the rocking of the ship and heard calls, laughs, cries, and children's screams. They saw again the over-filled ship's compartment without windows and smelled the appalling stench of vomit, urine, and sweat. And always and always, the haunting memory of the dear, little, dead Margreth.

In later life, Christian applied for and received a small veterans pension, and after his life partner of more than fifty years went to her final rest, he moved into the Old Soldiers and Sailors Home in Quincy, IL, where he lived out the remaining years of his life.

Although Andrew Lewis Gruber was not the eldest son, he came into possession of the family farm, and he and his wife Tresa Ellen Tuley lived and farmed there and raised their four children, and the land has continued in the family up to the present time.

I am indebted to Ursula Lehmann-Gugolz of Berne, Switzerland, for much of the information in this chapter.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement