*** her husband's plot at Arlington National Cemetery.

*** on June 16, 1979 the Wolfkeils held a memorial service in Wilkes-Barre for Wayne. A plaque with his name on it was placed at a cemetery. But nothing was buried.

For now, only Anne Wolfkeil is buried in her husband's plot at Arlington National Cemetery.

You may be gone, no longer living on this earth; but you will live on - in the memories of your family and friends. There will always be a part of you living in your family who knew you and loved you. You will live on because we remember you!

WAYNE BENJAMIN WOLFKEIL - Air Force COL - O6

Duty: A1H Skyraider Pilot

Age: 36

Race: Caucasian

Date of Birth Mar 7, 1932

From: WILKES BARRE, PA

Religion: PRESBYTERIAN

Marital Status: Married to Corp Anne Marie Wolfkeil. She was Born - Sep. 15, 1932, Died - Oct. 23, 2001 Anne Wolfkeil died in Colorado Springs, Colorado (El Paso County) at the age of 69 years old.. Buried in Arlington National Cemetery. she was from Colorado Springs, Colorado. Former Corporal, US Army. She served at the Pentagon, during the Korean War. She is survived by her husband, Colonel Wayne Wolfkeil (Refused to believe he was dead), two sons, David Wayne and Mark, and two daughters, Maura Proctor and Nikki Wolfkeil. He has two younger sisters and a brother.

Parents:

***** Cenotaph is located at Hanover Green Cemetery, Hanover Twp, PA 18706, not Wilkes-Barre City Cemetery.

Joan Cavanaugh

June 5, 2016

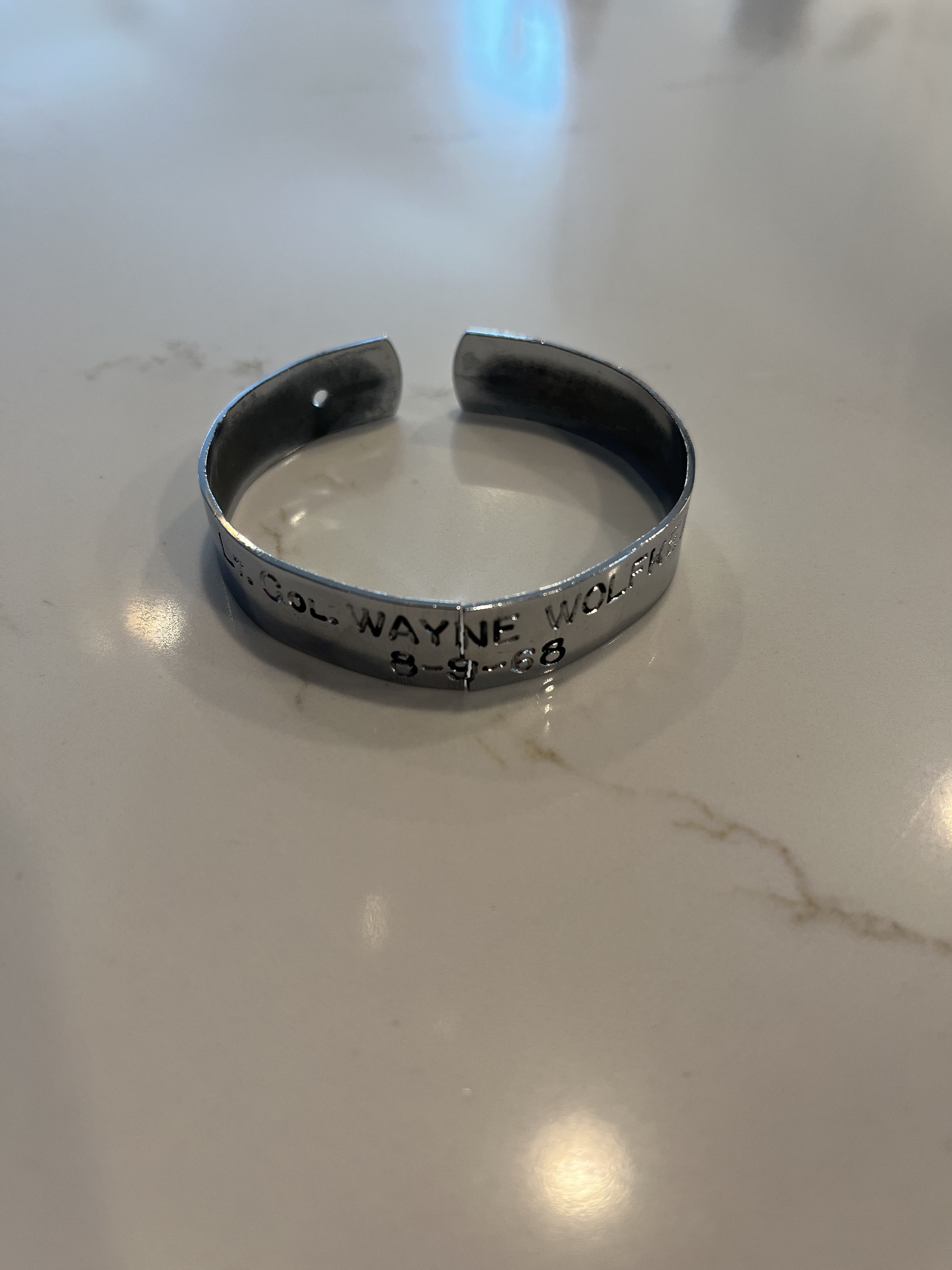

His tour began on Aug 9, 1968

Casualty was on Aug 9, 1968

In LZ, LAOS

Hostile, died while missing, FIXED WING - PILOT

AIR LOSS, CRASH ON LAND

Body was not recovered

Panel 49W - Line 37

Other Personnel in Incident: (none missing)

The A1 Skyraider ("Spad") had a varied role in Vietnam, such as flying rescue, close air support and forward air control (FAC) missions.

Major Wayne B. Wolfkeil was a pilot assigned to the 6th Special Operations Squadron at Pleiku Airbase in South Vietnam.

On August 9, 1968, Wolfkeil was assigned an operational mission over Laos as the number two aircraft in a flight of two.

About 25 miles west of the city of Dak To, (South Vietnam), in Attopeu Province, Laos, Wolfkeil's aircraft was seen to make a sharp right turn and crash, exploding on impact.

No parachute was seen, and no emergency radio beeper signals were heard.

Wayne B. Wolfkeil was promoted to the rank of Colonel during the period he was maintained missing.

********************************

Eleven years after he became missing, the U.S. declared him dead, based on no specific information that he was alive. He was a hero. Wayne B. Wolfkeil was promoted to the rank of Colonel during the period he was maintained missing. Eleven years after he became missing, the U.S. declared him dead, based on no specific information that he was alive.

*********************************************

Penn State's Wayne Wolfkeil: A war story with no ending

Former Nittany Lion Wayne Wolfkeil was shot down in Laos in 1968. No remains were ever found.

By FRANK BODANI

Daily Record/Sunday News

The knock on the door came in the afternoon.

A 13-year-old David Wolfkeil went to answer it. He was home watching his two younger sisters and brother while his mother bought groceries at the commissary.

He was an Air Force brat in 1968. He lived with his military parents just off base in Colorado Springs, Colo., in a three-bedroom brick home with green wood siding.

David opened the door.

A couple of military officers in pressed dress blues stood on the porch. A Catholic priest stood next to them.

The boy didn't know why they were there. He let them in and they sat down and made small talk until his mother returned. When she walked in, her eyes widened. She didn't say a word. She nearly dropped the brown bags in her hands, pushing them into David. She walked over to meet those men.

That was more than 40 years ago.

But he will remember his mother's face forever.

"I knew," he said, "because she knew."

* * *

Wayne Wolfkeil, the father and the fighter pilot, looked as if he had been cut from old oak, a solid slab of wood wearing easy and slow over the years.

He smelled of Cuban cigars and leather soaked in jet fuel.

He smiled big. He wore big black leather boots. He flew big planes. He was 6 feet tall, maybe a bit more, and weighed more than 200 pounds. Everyone seemed to know him, especially back in Wilkes-Barre, where he grew up and married his hometown sweetheart. He also played football at Penn State. Thank God for that, and for the military back then. Wolfkeil came from coal-mining stock and was destined for some kind of job that would dirty his hands and break his back, if not for the ROTC and that football scholarship.

At Penn State, he played for head coach Rip Engle and an assistant named Joe Paterno. The high-energy Paterno was barely older than his players back then, and he confronted Wolfkeil's future wife about taking too much of the running back's time, distracting him from his studies.

Wolfkeil's senior season was 1953 and his unremarkable career - he lettered just once - ended with an unremarkable 6-3 record. Nonetheless, he was part of one of the most eclectic mix of Nittany Lions ever assembled.

His teammates included NFL Hall of Famer Lenny Moore, social icon Rosey Grier and NBA player and lawyer Jesse Arnelle.

Even now, Paterno remembers Wolfkeil.

"He was a hard worker, not a great football player, but a delightful person and a great team man. He was a leader," Paterno said in early November.

Those character traits would drive Wolfkeil into the Air Force upon graduating from Penn State.

But it wasn't until the Vietnam War, years later, that everything changed.

The United States' air presence was building through the mid-1960s, and Wolfkeil finally received his orders, no matter that he was 36. He was a military lifer and he wanted to fight for his country, and experienced pilots were in demand.

On the day he left for basic training in 1968, his kids were still asleep and he didn't get the chance to say good-bye.

"I wasn't worried about nothing at that age. I just thought Dad would survive and go on to another job," said David Wolfkeil, now 56 and living in Niceville, Fla. "He always came home. That's just the way it was."

That seemed sensible enough. Wayne Wolfkeil might have felt more comfortable in the air than on the ground, having flown countless peacetime missions through nearly 15 years.

Take that time in 1962 when he and another officer were flying in the Syracuse, N.Y. area. They began experiencing engine trouble five minutes after takeoff.

They both ejected from the plane and parachuted 5,000 feet to safety, barely missing a lake and landing in a tree.

And yet, things seemed different with Vietnam. He paid a visit to best friends Nancy and Dean DeTar the evening before shipping out, and they sensed it.

"The minute he was at our door he seemed to have a cross on his forehead. You could tell," Nancy DeTar said recently. "When Wayne left that night, I said (to Dean), 'That man, we're never going to see him again.' It's not something you tell anybody. I knew it in my soul."

Reliving the scene recently struck her just as it did more than four decades ago.

Once again, she found a place alone and cried.

* * *

No Penn State football player had died in service to his country since World War I, when Red Bebout and Levi Lamb, stars of the unbeaten 1912 team, were killed in France barely two months apart.

There was not a single casualty in World War II or Korea.

And not one since, in the Persian Gulf, Iraq or Afghanistan.

The only deaths in these past 100 years have been two fighter pilot teammates, only a year apart.

Maj. Fred William "Ted" Shattuck was a halfback who dropped out of Penn State after the 1951 season. He died on July 19, 1969, a couple of days after his plane exploded as he was taking off on a mission from Thailand.

Wolfkeil, though, remains the only Penn State football letterman since World War I killed during combat.

Go back to that heavy, gray afternoon in '68 when the military officers and the priest showed up at the house in Colorado Springs. In a way, the most agonizing part was that they couldn't give the most important answer.

They could only say Wolfkeil was missing in action.

The devastation mixed with mystery began to slowly suffocate in ways unimaginable, especially to 13-year-old David and his mother.

Military wives from down the street showed up and took the children downstairs that day. David, the oldest, was summoned first to hear the news. He understood what "shot down" and "missing in action" meant.

"I sat on the floor and cried like a baby," he said.

"After that it was like a Sunday, very quiet around the house. Everyone was walking on eggshells."

But there wasn't time for lives to stop. Ann Wolfkeil cared for her four children and relentlessly lobbied the government and military for answers about her husband. She pushed David into sports, did everything to make sure he was occupied.

He was simply numb through the ensuing year. Teachers and coaches looked after him as best they could, but that only went so far.

His mother was too busy with her younger children to attend his track meets and football games.

He didn't have a father in the stands.

"Sometimes it made me mad and sometimes you just let it flow through you," David Wolfkeil said.

"You don't get over it, you just adapt, and you fantasize about your dad coming home. You dream about it all the time. You're hoping he's part of the POWs. They hadn't released their names yet. You kept your fingers crossed that he was there."

Life grinded on and he went to college and eventually graduated. He was good in football but much smaller than his father. He was best at running and earned a full ride to the University of Missouri, where he specialized in the 400 meters.

Paterno, a veteran head coach by then, knew of the Wolfkeils' situation. In 1970, David and his mother talked with Sue Paterno and watched in the stands in Boulder as the University of Colorado snapped Penn State's nation-best 31-game unbeaten streak.

About that time, the Air Force promoted Wayne Wolfkeil from a major to lieutenant colonel, the first of three promotions after his MIA status. They not only were measures of honor for a possible life lost but also a means of increasing benefits to his family.

He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and a Purple Heart.

Four years later, in 1974, Joe Paterno sent David Wolfkeil a letter of encouragement that is framed and still hangs in his Florida home.

Not longer after, the U.S. government released the names of all prisoners of war. Wayne Wolfkeil wasn't one of them.

That day sticks with David more than the one seven years earlier when he learned his father had been shot down.

This was different. This was worse.

"It still chokes me up. It brings back so much emotion," David Wolfkeil said.

It was as if hope had finally expired.

* * *

The veteran pilots became the best of friends.

Wayne Wolfkeil and Linden Gill met in Colorado Springs two years earlier and went through each step of Vietnam War training together. They eventually shipped to Bangkok for some rest before their final destination.

"Finally, after a while, we were thinking what it would be like in combat and to go to Vietnam and do some shooting and drop some bombs," Gill said by phone from his home in Tennessee.

The two enjoyed a "pretty good living" in cabins - when Vietcong rocket mortars weren't exploding next to their barracks in the middle of the night, lifting pickup trucks off the ground. Instead of diving into dug-out bomb shelters full of spiders and snakes, they simply sought cover from the shelling under their mattresses.

Wolfkeil was working out of the 6th Special Operations Squadron in Vietnam. He had been flying there for only 15 days when, on Aug. 9, he was assigned to a typical 90-minute mission over nearby Laos. He piloted one of the standard A1 Skyraiders that flew low and slow to provide pounding cover for ground forces and helicopters.

Typed letters from the Department of the Air Force, dated Aug. 10-11, 1968, were sent to the Wolfkeil family. They provided the following details:

Wayne Wolfkeil "was flying as wingman in a flight of two AIH aircraft when they were directed by a Forward Air Controller to attempt to silence an enemy troop emplacement. Following his lead pilot, Wayne made a pass at the target and was observed to be in a right turn when his aircraft impacted with the ground on a heavily wooded hillside and exploded.

"No parachute was seen, no beeper was heard, and no voice contact was made with him."

Weather abruptly turned poor, fog and clouds shrouding the area for days. Two weeks after he was shot down, U.S. ground forces finally reached the crash site, finding the scorched earth where his shattered craft hit, about four miles into Laos.

Bits and pieces of a helmet were recovered.

And that was it.

Another pilot told Gill how ground fire hit Wolfkeil's ordnance load under his wings - maybe 12,000 pounds of explosives, to go with 300 pounds of gasoline - which ignited his plane into "a ball of flames. There was no way he could have lived through that."

Gill was part of the recovery mission. He flew one of the Skyraiders to protect the Green Berets who hiked to the crash site and found only those helmet shards.

When the Green Berets left, Linden and other pilots "cleaned off that mountain" with bombs and gas, a measure of retribution for a friend.

Then it was Linden's duty to sort and organize Wolfkeil's possessions and secure his room. He sifted through piles of letters and voice tapes, as standard procedure.

He played a tape Wolfkeil received from home shortly after arriving in Vietnam. It was David's voice:

"Dad, you remember that cigar you left on the ash tray on the coffee table?

"We'll leave it there until you come back ..."

* * *

From the day he answered the knock on the door as a teenager, David felt something "in my gut" that his father would never come home.

But his mother never gave up.

She searched for answers and prodded for more government help, and she prayed.

She never remarried.

Even after he was reported missing, the family continued to send Wayne letters, cards, packages.

"Some of the flyers who were with my son went to Colorado Springs and told her to forget about him," Wayne's father, Adam Wolfkeil, told the Wilkes-Barre Times Leader in 1982. "But she ordered them out. She wouldn't give up."

It was difficult to find any kind of peace, not in 1976 when he was promoted to the rank of colonel. Certainly not in 1979 when the government officially declared Wayne Wolfkeil as "killed in action."

They didn't have any proof. It had simply been too many years without evidence otherwise.

His family tried to provide what closure they could.

At 1400 hours on June 16, 1979 the Wolfkeils held a memorial service in Wilkes-Barre for Wayne.

A plaque with his name on it was placed at a cemetery.

But nothing was buried.

"That all wore her out mentally," David Wolfkeil said of his mother.

She died a decade ago, believing her husband could still be alive.

"You do what everybody does: You hold your breath and assume he's a POW. That, somehow, magic would happen," said Jack Wolfkeil, Wayne's older brother, who now lives in Georgia. "You don't know what families do to tough it out."

David Wolfkeil understands. If his mother never gave up, then how could he?

"You fantasize when you're younger, 'What if he's living in the jungle all those years?' It's all fantasy, but that's what you do in life and it keeps you going sometimes."

* * *

In the end, this story is as much about the son as the father.

David was the only one of his siblings with a sustained memory of him. And he was the one who followed his father into the Air Force and stayed for 14 years.

Their paths were similar - David Wolfkeil, too, was stationed in an old World War II barracks in the Philippines.

"I felt very close to my father, to the point it was almost eerie. When I would walk around the jets I almost expected to see him walk around the corner."

He even flew training missions (David was a navigator) to Thailand, only 80 miles from where his father was shot down.

David ended up traveling the world like him, too. His daughter, Veronika, was born in Germany when he was stationed overseas.

She even carried on the family's athletic tradition, recently finishing her senior season on a partial soccer scholarship at the University of Alabama.

And when she finally pushed hard about knowing her grandfather, David Wolfkeil committed to telling her everything. He told her the stories and showed her every picture and took her to Washington, D.C., to see his name on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall.

Yet, there is a final wish, a desire to be filled that still nudges after all these years.

Bringing home some of his remains, even now, could finally produce the kind of peace Wayne Wolfkeil's wife and parents never knew.

For now, only Anne Wolfkeil is buried in her husband's plot at Arlington National Cemetery.

"You want confirmation that life did come to an end and you know where it happened," brother Jack Wolfkeil said. "So you're not burying a memory, you're burying remains, no matter how insignificant."

David Wolfkeil said military searches are still operating in Laos and, after all of these years, he believes they could be close to where his father was shot down.

He lives his life but still hopes and waits, patiently waits for some kind of answer.

His father is much more than an interesting football footnote at Penn State.

"It's up to me and my family to keep ...," he said, his words trailing away. "This story is not done yet."

******************************

.

*** her husband's plot at Arlington National Cemetery.

*** on June 16, 1979 the Wolfkeils held a memorial service in Wilkes-Barre for Wayne. A plaque with his name on it was placed at a cemetery. But nothing was buried.

For now, only Anne Wolfkeil is buried in her husband's plot at Arlington National Cemetery.

You may be gone, no longer living on this earth; but you will live on - in the memories of your family and friends. There will always be a part of you living in your family who knew you and loved you. You will live on because we remember you!

WAYNE BENJAMIN WOLFKEIL - Air Force COL - O6

Duty: A1H Skyraider Pilot

Age: 36

Race: Caucasian

Date of Birth Mar 7, 1932

From: WILKES BARRE, PA

Religion: PRESBYTERIAN

Marital Status: Married to Corp Anne Marie Wolfkeil. She was Born - Sep. 15, 1932, Died - Oct. 23, 2001 Anne Wolfkeil died in Colorado Springs, Colorado (El Paso County) at the age of 69 years old.. Buried in Arlington National Cemetery. she was from Colorado Springs, Colorado. Former Corporal, US Army. She served at the Pentagon, during the Korean War. She is survived by her husband, Colonel Wayne Wolfkeil (Refused to believe he was dead), two sons, David Wayne and Mark, and two daughters, Maura Proctor and Nikki Wolfkeil. He has two younger sisters and a brother.

Parents:

***** Cenotaph is located at Hanover Green Cemetery, Hanover Twp, PA 18706, not Wilkes-Barre City Cemetery.

Joan Cavanaugh

June 5, 2016

His tour began on Aug 9, 1968

Casualty was on Aug 9, 1968

In LZ, LAOS

Hostile, died while missing, FIXED WING - PILOT

AIR LOSS, CRASH ON LAND

Body was not recovered

Panel 49W - Line 37

Other Personnel in Incident: (none missing)

The A1 Skyraider ("Spad") had a varied role in Vietnam, such as flying rescue, close air support and forward air control (FAC) missions.

Major Wayne B. Wolfkeil was a pilot assigned to the 6th Special Operations Squadron at Pleiku Airbase in South Vietnam.

On August 9, 1968, Wolfkeil was assigned an operational mission over Laos as the number two aircraft in a flight of two.

About 25 miles west of the city of Dak To, (South Vietnam), in Attopeu Province, Laos, Wolfkeil's aircraft was seen to make a sharp right turn and crash, exploding on impact.

No parachute was seen, and no emergency radio beeper signals were heard.

Wayne B. Wolfkeil was promoted to the rank of Colonel during the period he was maintained missing.

********************************

Eleven years after he became missing, the U.S. declared him dead, based on no specific information that he was alive. He was a hero. Wayne B. Wolfkeil was promoted to the rank of Colonel during the period he was maintained missing. Eleven years after he became missing, the U.S. declared him dead, based on no specific information that he was alive.

*********************************************

Penn State's Wayne Wolfkeil: A war story with no ending

Former Nittany Lion Wayne Wolfkeil was shot down in Laos in 1968. No remains were ever found.

By FRANK BODANI

Daily Record/Sunday News

The knock on the door came in the afternoon.

A 13-year-old David Wolfkeil went to answer it. He was home watching his two younger sisters and brother while his mother bought groceries at the commissary.

He was an Air Force brat in 1968. He lived with his military parents just off base in Colorado Springs, Colo., in a three-bedroom brick home with green wood siding.

David opened the door.

A couple of military officers in pressed dress blues stood on the porch. A Catholic priest stood next to them.

The boy didn't know why they were there. He let them in and they sat down and made small talk until his mother returned. When she walked in, her eyes widened. She didn't say a word. She nearly dropped the brown bags in her hands, pushing them into David. She walked over to meet those men.

That was more than 40 years ago.

But he will remember his mother's face forever.

"I knew," he said, "because she knew."

* * *

Wayne Wolfkeil, the father and the fighter pilot, looked as if he had been cut from old oak, a solid slab of wood wearing easy and slow over the years.

He smelled of Cuban cigars and leather soaked in jet fuel.

He smiled big. He wore big black leather boots. He flew big planes. He was 6 feet tall, maybe a bit more, and weighed more than 200 pounds. Everyone seemed to know him, especially back in Wilkes-Barre, where he grew up and married his hometown sweetheart. He also played football at Penn State. Thank God for that, and for the military back then. Wolfkeil came from coal-mining stock and was destined for some kind of job that would dirty his hands and break his back, if not for the ROTC and that football scholarship.

At Penn State, he played for head coach Rip Engle and an assistant named Joe Paterno. The high-energy Paterno was barely older than his players back then, and he confronted Wolfkeil's future wife about taking too much of the running back's time, distracting him from his studies.

Wolfkeil's senior season was 1953 and his unremarkable career - he lettered just once - ended with an unremarkable 6-3 record. Nonetheless, he was part of one of the most eclectic mix of Nittany Lions ever assembled.

His teammates included NFL Hall of Famer Lenny Moore, social icon Rosey Grier and NBA player and lawyer Jesse Arnelle.

Even now, Paterno remembers Wolfkeil.

"He was a hard worker, not a great football player, but a delightful person and a great team man. He was a leader," Paterno said in early November.

Those character traits would drive Wolfkeil into the Air Force upon graduating from Penn State.

But it wasn't until the Vietnam War, years later, that everything changed.

The United States' air presence was building through the mid-1960s, and Wolfkeil finally received his orders, no matter that he was 36. He was a military lifer and he wanted to fight for his country, and experienced pilots were in demand.

On the day he left for basic training in 1968, his kids were still asleep and he didn't get the chance to say good-bye.

"I wasn't worried about nothing at that age. I just thought Dad would survive and go on to another job," said David Wolfkeil, now 56 and living in Niceville, Fla. "He always came home. That's just the way it was."

That seemed sensible enough. Wayne Wolfkeil might have felt more comfortable in the air than on the ground, having flown countless peacetime missions through nearly 15 years.

Take that time in 1962 when he and another officer were flying in the Syracuse, N.Y. area. They began experiencing engine trouble five minutes after takeoff.

They both ejected from the plane and parachuted 5,000 feet to safety, barely missing a lake and landing in a tree.

And yet, things seemed different with Vietnam. He paid a visit to best friends Nancy and Dean DeTar the evening before shipping out, and they sensed it.

"The minute he was at our door he seemed to have a cross on his forehead. You could tell," Nancy DeTar said recently. "When Wayne left that night, I said (to Dean), 'That man, we're never going to see him again.' It's not something you tell anybody. I knew it in my soul."

Reliving the scene recently struck her just as it did more than four decades ago.

Once again, she found a place alone and cried.

* * *

No Penn State football player had died in service to his country since World War I, when Red Bebout and Levi Lamb, stars of the unbeaten 1912 team, were killed in France barely two months apart.

There was not a single casualty in World War II or Korea.

And not one since, in the Persian Gulf, Iraq or Afghanistan.

The only deaths in these past 100 years have been two fighter pilot teammates, only a year apart.

Maj. Fred William "Ted" Shattuck was a halfback who dropped out of Penn State after the 1951 season. He died on July 19, 1969, a couple of days after his plane exploded as he was taking off on a mission from Thailand.

Wolfkeil, though, remains the only Penn State football letterman since World War I killed during combat.

Go back to that heavy, gray afternoon in '68 when the military officers and the priest showed up at the house in Colorado Springs. In a way, the most agonizing part was that they couldn't give the most important answer.

They could only say Wolfkeil was missing in action.

The devastation mixed with mystery began to slowly suffocate in ways unimaginable, especially to 13-year-old David and his mother.

Military wives from down the street showed up and took the children downstairs that day. David, the oldest, was summoned first to hear the news. He understood what "shot down" and "missing in action" meant.

"I sat on the floor and cried like a baby," he said.

"After that it was like a Sunday, very quiet around the house. Everyone was walking on eggshells."

But there wasn't time for lives to stop. Ann Wolfkeil cared for her four children and relentlessly lobbied the government and military for answers about her husband. She pushed David into sports, did everything to make sure he was occupied.

He was simply numb through the ensuing year. Teachers and coaches looked after him as best they could, but that only went so far.

His mother was too busy with her younger children to attend his track meets and football games.

He didn't have a father in the stands.

"Sometimes it made me mad and sometimes you just let it flow through you," David Wolfkeil said.

"You don't get over it, you just adapt, and you fantasize about your dad coming home. You dream about it all the time. You're hoping he's part of the POWs. They hadn't released their names yet. You kept your fingers crossed that he was there."

Life grinded on and he went to college and eventually graduated. He was good in football but much smaller than his father. He was best at running and earned a full ride to the University of Missouri, where he specialized in the 400 meters.

Paterno, a veteran head coach by then, knew of the Wolfkeils' situation. In 1970, David and his mother talked with Sue Paterno and watched in the stands in Boulder as the University of Colorado snapped Penn State's nation-best 31-game unbeaten streak.

About that time, the Air Force promoted Wayne Wolfkeil from a major to lieutenant colonel, the first of three promotions after his MIA status. They not only were measures of honor for a possible life lost but also a means of increasing benefits to his family.

He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and a Purple Heart.

Four years later, in 1974, Joe Paterno sent David Wolfkeil a letter of encouragement that is framed and still hangs in his Florida home.

Not longer after, the U.S. government released the names of all prisoners of war. Wayne Wolfkeil wasn't one of them.

That day sticks with David more than the one seven years earlier when he learned his father had been shot down.

This was different. This was worse.

"It still chokes me up. It brings back so much emotion," David Wolfkeil said.

It was as if hope had finally expired.

* * *

The veteran pilots became the best of friends.

Wayne Wolfkeil and Linden Gill met in Colorado Springs two years earlier and went through each step of Vietnam War training together. They eventually shipped to Bangkok for some rest before their final destination.

"Finally, after a while, we were thinking what it would be like in combat and to go to Vietnam and do some shooting and drop some bombs," Gill said by phone from his home in Tennessee.

The two enjoyed a "pretty good living" in cabins - when Vietcong rocket mortars weren't exploding next to their barracks in the middle of the night, lifting pickup trucks off the ground. Instead of diving into dug-out bomb shelters full of spiders and snakes, they simply sought cover from the shelling under their mattresses.

Wolfkeil was working out of the 6th Special Operations Squadron in Vietnam. He had been flying there for only 15 days when, on Aug. 9, he was assigned to a typical 90-minute mission over nearby Laos. He piloted one of the standard A1 Skyraiders that flew low and slow to provide pounding cover for ground forces and helicopters.

Typed letters from the Department of the Air Force, dated Aug. 10-11, 1968, were sent to the Wolfkeil family. They provided the following details:

Wayne Wolfkeil "was flying as wingman in a flight of two AIH aircraft when they were directed by a Forward Air Controller to attempt to silence an enemy troop emplacement. Following his lead pilot, Wayne made a pass at the target and was observed to be in a right turn when his aircraft impacted with the ground on a heavily wooded hillside and exploded.

"No parachute was seen, no beeper was heard, and no voice contact was made with him."

Weather abruptly turned poor, fog and clouds shrouding the area for days. Two weeks after he was shot down, U.S. ground forces finally reached the crash site, finding the scorched earth where his shattered craft hit, about four miles into Laos.

Bits and pieces of a helmet were recovered.

And that was it.

Another pilot told Gill how ground fire hit Wolfkeil's ordnance load under his wings - maybe 12,000 pounds of explosives, to go with 300 pounds of gasoline - which ignited his plane into "a ball of flames. There was no way he could have lived through that."

Gill was part of the recovery mission. He flew one of the Skyraiders to protect the Green Berets who hiked to the crash site and found only those helmet shards.

When the Green Berets left, Linden and other pilots "cleaned off that mountain" with bombs and gas, a measure of retribution for a friend.

Then it was Linden's duty to sort and organize Wolfkeil's possessions and secure his room. He sifted through piles of letters and voice tapes, as standard procedure.

He played a tape Wolfkeil received from home shortly after arriving in Vietnam. It was David's voice:

"Dad, you remember that cigar you left on the ash tray on the coffee table?

"We'll leave it there until you come back ..."

* * *

From the day he answered the knock on the door as a teenager, David felt something "in my gut" that his father would never come home.

But his mother never gave up.

She searched for answers and prodded for more government help, and she prayed.

She never remarried.

Even after he was reported missing, the family continued to send Wayne letters, cards, packages.

"Some of the flyers who were with my son went to Colorado Springs and told her to forget about him," Wayne's father, Adam Wolfkeil, told the Wilkes-Barre Times Leader in 1982. "But she ordered them out. She wouldn't give up."

It was difficult to find any kind of peace, not in 1976 when he was promoted to the rank of colonel. Certainly not in 1979 when the government officially declared Wayne Wolfkeil as "killed in action."

They didn't have any proof. It had simply been too many years without evidence otherwise.

His family tried to provide what closure they could.

At 1400 hours on June 16, 1979 the Wolfkeils held a memorial service in Wilkes-Barre for Wayne.

A plaque with his name on it was placed at a cemetery.

But nothing was buried.

"That all wore her out mentally," David Wolfkeil said of his mother.

She died a decade ago, believing her husband could still be alive.

"You do what everybody does: You hold your breath and assume he's a POW. That, somehow, magic would happen," said Jack Wolfkeil, Wayne's older brother, who now lives in Georgia. "You don't know what families do to tough it out."

David Wolfkeil understands. If his mother never gave up, then how could he?

"You fantasize when you're younger, 'What if he's living in the jungle all those years?' It's all fantasy, but that's what you do in life and it keeps you going sometimes."

* * *

In the end, this story is as much about the son as the father.

David was the only one of his siblings with a sustained memory of him. And he was the one who followed his father into the Air Force and stayed for 14 years.

Their paths were similar - David Wolfkeil, too, was stationed in an old World War II barracks in the Philippines.

"I felt very close to my father, to the point it was almost eerie. When I would walk around the jets I almost expected to see him walk around the corner."

He even flew training missions (David was a navigator) to Thailand, only 80 miles from where his father was shot down.

David ended up traveling the world like him, too. His daughter, Veronika, was born in Germany when he was stationed overseas.

She even carried on the family's athletic tradition, recently finishing her senior season on a partial soccer scholarship at the University of Alabama.

And when she finally pushed hard about knowing her grandfather, David Wolfkeil committed to telling her everything. He told her the stories and showed her every picture and took her to Washington, D.C., to see his name on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall.

Yet, there is a final wish, a desire to be filled that still nudges after all these years.

Bringing home some of his remains, even now, could finally produce the kind of peace Wayne Wolfkeil's wife and parents never knew.

For now, only Anne Wolfkeil is buried in her husband's plot at Arlington National Cemetery.

"You want confirmation that life did come to an end and you know where it happened," brother Jack Wolfkeil said. "So you're not burying a memory, you're burying remains, no matter how insignificant."

David Wolfkeil said military searches are still operating in Laos and, after all of these years, he believes they could be close to where his father was shot down.

He lives his life but still hopes and waits, patiently waits for some kind of answer.

His father is much more than an interesting football footnote at Penn State.

"It's up to me and my family to keep ...," he said, his words trailing away. "This story is not done yet."

******************************

.

Gravesite Details

on June 16, 1979 the Wolfkeils held a memorial service in Wilkes-Barre for Wayne. A plaque with his name on it was placed at a cemetery. But nothing was buried.