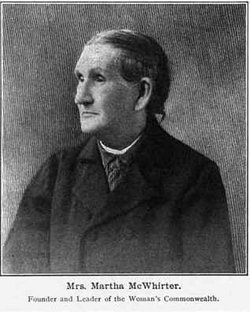

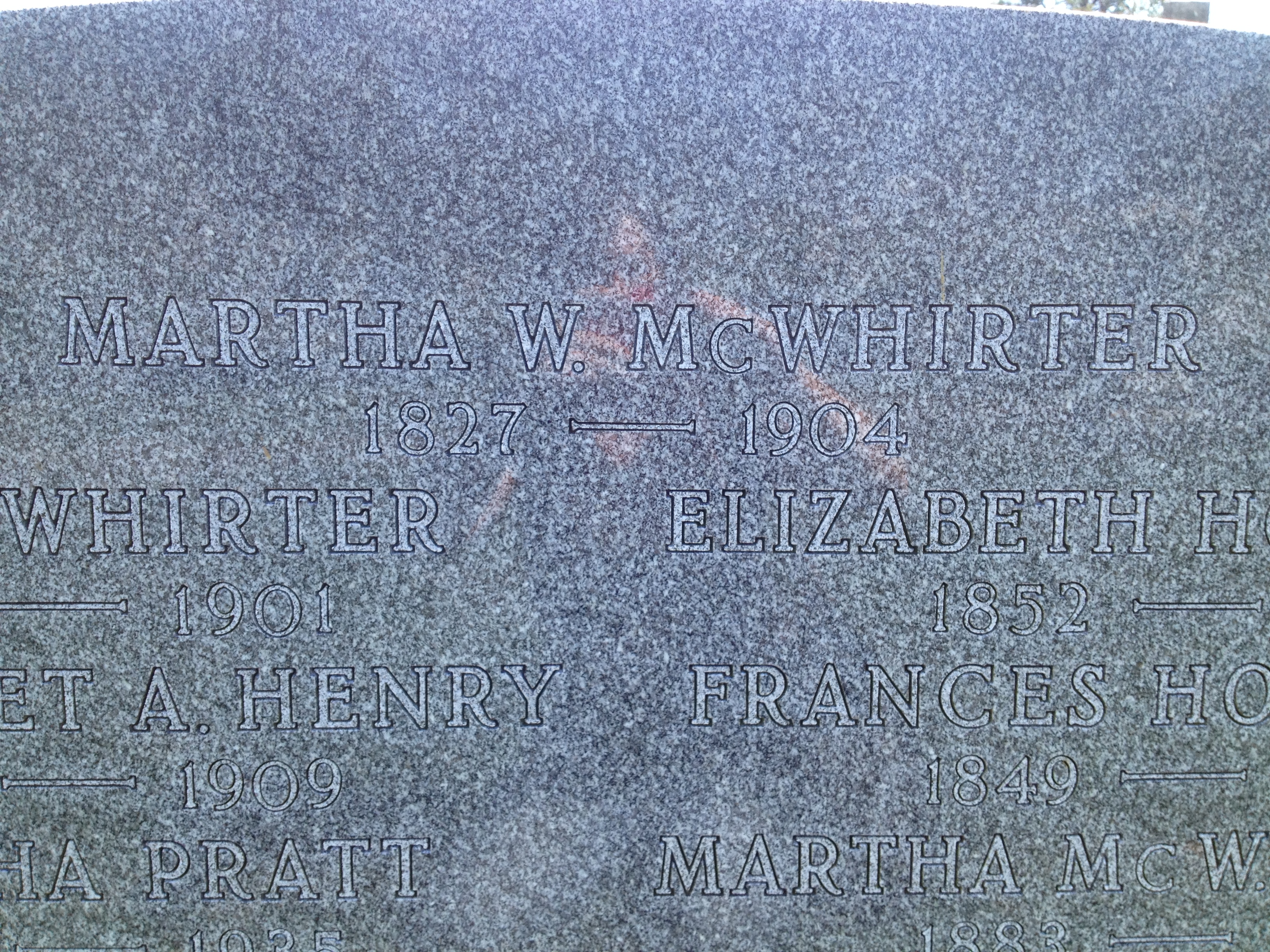

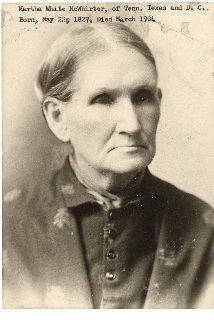

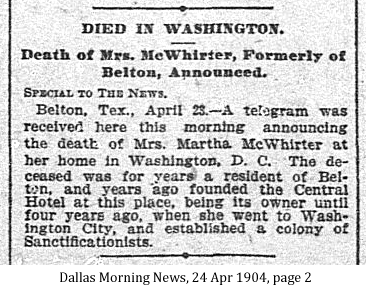

Martha White McWhirter, founder and leader of the Belton Woman's Commonwealth, was born on May 17, 1827, in Gainesboro, Tennessee, the daughter of a Jackson County planter. In 1845 she married George M. McWhirter, an attorney and farmer. The McWhirters moved to Bell County, Texas, in 1855, and settled first on Salado Creek, near the site of present Armstrong. Nine or ten years later they moved to Belton, where George McWhirter operated a store and had an interest in a flour mill. The McWhirters had twelve children, only six of whom survived. Martha McWhirter had joined the Methodist Church in Tennessee at the age of sixteen, and in Belton she and her husband helped establish the interdenominational Union Sunday School, to which they remained loyal even after the community acquired a Methodist congregation in 1870. She also led a women's prayer group that met weekly in the members' homes. In 1866, after the deaths of her brother and two of her children, she began to believe that God was chastising her. After a prayerful night she had a vision that convinced her that she had been "sanctified," or filled with the Holy Spirit. She shared her revelation with the women in her prayer group, and other members began to pray successfully for sanctification. Mrs. McWhirter's deepening commitment to unorthodox religious views eventually caused a serious rift in the community. Many of her growing band of female followers were unhappy in their domestic affairs, and she herself accused her husband of making improper advances toward a servant girl. She claimed to have had a revelation in which the sanctified were instructed to separate themselves from the undevout, and consequently directed her followers to continue to perform their household duties while minimizing social contact with their husbands and abstaining from conjugal relations. Eventually the women began to leave their homes to live and work communally. As the McWhirter house began to fill up with "Sanctified Sisters," George and Martha separated permanently. Without her husband's permission she had a house built for a homeless sister on one of his lots, claiming that the money she had brought to their marriage gave her a moral right to the property. Despite his anger George did not interfere when the women continued to build houses; he defended his estranged wife against critical townspeople and left her his estate when he died in 1887. While still living with her husband Martha McWhirter had avoided asking him for household money by marketing eggs, butter, and baked goods. As the financial planner for the Woman's Commonwealth she directed her followers in a variety of enterprises that made the group financially secure in a relatively short time. The Sanctificationists' economic success helped dissipate much of the town's hostility, and McWhirter became the first woman elected to the city Board of Trade. She contributed to the community fund to help attract a railroad to Belton, and her name appeared on the cornerstone of the Belton opera house. She continued to lead the Woman's Commonwealth even after the members retired from business in 1899 and bought property in Washington, D.C., and Mount Pleasant, Maryland. She died in the Washington area on April 21, 1904.

The group was also known as the Belton Woman's Commonwealth and the True Church Colony. The Sanctified Sisters was a somewhat derisive term that townspeople in Belton used to describe the group. The group's beliefs, and the way they acted upon those beliefs, were considered scandalous.

The group was started by Martha White McWhirter, usually referred to in historical texts as Mrs. George M. McWhirter. The couple met and married in Tennessee and moved to Bell County, near what became the Armstrong Community, in 1855.

They settled in Belton about 1866 where George entered the mercantile business and had an interest in a flour mill.

About the time George returned from the Civil War, where he attained the rank of Major in the Confederate Army, Martha McWhirter suffered something of a spiritual crisis. A brother and two of her children had died, which she interpreted as punishment from God.

Mrs. McWhirter prayed fervently and claimed to have a vision accompanied by an audible voice that told her she had been "sanctified," or filled with the Holy Spirit.

Members of her prayer group soon came to her with the news that they too had been sanctified. They became sisters in sanctification.

Ms. McWhirter's officially broke with the Methodist church in 1870 when the Methodists erected a building and proposed to organize a Methodist Sunday School to replace Belton's nonsectarian Union Sunday School, where her husband was a superintendent.

In time, the group completely cut itself off from all other organized church groups and became a religious entity all unto itself.

Part of the group's doctrine included the then unheard-of belief that men and women were equal in the eyes of God. One of Ms. McWhirter's divine revelations was that it was no longer a woman's duty to remain with a husband who bossed and controlled her, that God had made man and woman equal.

"We were to come out and be the 'peculiar people,'" she said.

The True Church Colony was open to men but most declined membership, probably because they took issue with the group's vows of celibacy with unsanctified mates.

Two brothers from Scotland, members of the Sanctificationist Church back home, joined the group. This displeased a group of Belton men, who took the brothers to the woods, stripped and flogged them. Lunacy charges were filed against the men when they refused to repent. The brothers won their case in court - something about the freedom of religion - but they never went back to True Church Colony again, which might have definitively proven their sanity.

The group evolved into a commune that held all wealth in common and which also doubled as something of a battered women's center, owing to the sometime violent reactions of husbands to their wives' newfound sanctity.

In its early days the group made ends meet by selling vegetables, chickens, butter and eggs. The business grew to include a laundry, a bakery, and a boarding house along with hotels in Belton and Waco.

The women's prosperity eventually brought them a measure of respect in Belton by virtue of the fact that they made a lot of money. Martha McWhirter even became the first woman to sit on the Belton's board of trade.

Mrs. McWhirter was the group's undisputed leader and she ruled with an iron fist and a will to match. The laws she set up were absolute and inflexible.

One of the laws stipulated that no sanctified woman could be the wife of an unsanctified husband, and visa versa. Women left their husbands in number high enough to draw attention from the community. Much of the community, especially the men, considered them little more than home wreckers.

Though the women seemed to have no qualms about leaving their husbands, neither did they protest when the husbands died and left them sizeable estates. In such a manner did the Sanctificationists inherit a homestead that became a headquarters for the colony.

Ms. McWhirter also received a sizeable inheritance from George, who left home after the couple's children had reached "the age of discretion." He spent the last years of his life in a room his wife fixed for him in his downtown office. The couple never spoke again. When he died in 1877, Ms. McWhirter said of her husband, "He believed in the sincerity of my religion and he always loved me."

At least one frustrated husband had his sanctified wife committed to an insane asylum but she was rescued by Mrs. McWhirter and received a $1,500 settlement from the state for being falsely committed - that freedom of religion thing again.

In 1900 the group sold or leased all its Texas property and went forth into the wider world, not to multiply but to look for a retirement home. They went north to the Great Lakes and south into Mexico but settled on Washington, D.C. where they bought a large house on Keenesaw Avenue.

The women were often seen out and about in the nation's capital, attending the theater and lectures and the galleries of Congress. They operated a farm in Maryland and a boarding house in Washington, D.C. The national press sometimes came calling. In spite of themselves, the women were almost celebrities.

Ms. McWhirter had believed for a long time that her days were numbered but she lived to be an old woman. "I used to worry much about death, but I think now that were are just in the dawn of the new dispensation when the Christ is to begin his reign of Peace on Earth," she said late in her life.

Martha McWhirter died in 1904 and Fannie Holtzclaw took over the as the commune's leader. The group dwindled away as its members died, the vow of celibacy doing away with the notion of any second generation Sanctificationists.

Martha Scheble, the last of the Sanctified Sisters, died on the Maryland farm in 1983 at the age of 101.

Martha White McWhirter, founder and leader of the Belton Woman's Commonwealth, was born on May 17, 1827, in Gainesboro, Tennessee, the daughter of a Jackson County planter. In 1845 she married George M. McWhirter, an attorney and farmer. The McWhirters moved to Bell County, Texas, in 1855, and settled first on Salado Creek, near the site of present Armstrong. Nine or ten years later they moved to Belton, where George McWhirter operated a store and had an interest in a flour mill. The McWhirters had twelve children, only six of whom survived. Martha McWhirter had joined the Methodist Church in Tennessee at the age of sixteen, and in Belton she and her husband helped establish the interdenominational Union Sunday School, to which they remained loyal even after the community acquired a Methodist congregation in 1870. She also led a women's prayer group that met weekly in the members' homes. In 1866, after the deaths of her brother and two of her children, she began to believe that God was chastising her. After a prayerful night she had a vision that convinced her that she had been "sanctified," or filled with the Holy Spirit. She shared her revelation with the women in her prayer group, and other members began to pray successfully for sanctification. Mrs. McWhirter's deepening commitment to unorthodox religious views eventually caused a serious rift in the community. Many of her growing band of female followers were unhappy in their domestic affairs, and she herself accused her husband of making improper advances toward a servant girl. She claimed to have had a revelation in which the sanctified were instructed to separate themselves from the undevout, and consequently directed her followers to continue to perform their household duties while minimizing social contact with their husbands and abstaining from conjugal relations. Eventually the women began to leave their homes to live and work communally. As the McWhirter house began to fill up with "Sanctified Sisters," George and Martha separated permanently. Without her husband's permission she had a house built for a homeless sister on one of his lots, claiming that the money she had brought to their marriage gave her a moral right to the property. Despite his anger George did not interfere when the women continued to build houses; he defended his estranged wife against critical townspeople and left her his estate when he died in 1887. While still living with her husband Martha McWhirter had avoided asking him for household money by marketing eggs, butter, and baked goods. As the financial planner for the Woman's Commonwealth she directed her followers in a variety of enterprises that made the group financially secure in a relatively short time. The Sanctificationists' economic success helped dissipate much of the town's hostility, and McWhirter became the first woman elected to the city Board of Trade. She contributed to the community fund to help attract a railroad to Belton, and her name appeared on the cornerstone of the Belton opera house. She continued to lead the Woman's Commonwealth even after the members retired from business in 1899 and bought property in Washington, D.C., and Mount Pleasant, Maryland. She died in the Washington area on April 21, 1904.

The group was also known as the Belton Woman's Commonwealth and the True Church Colony. The Sanctified Sisters was a somewhat derisive term that townspeople in Belton used to describe the group. The group's beliefs, and the way they acted upon those beliefs, were considered scandalous.

The group was started by Martha White McWhirter, usually referred to in historical texts as Mrs. George M. McWhirter. The couple met and married in Tennessee and moved to Bell County, near what became the Armstrong Community, in 1855.

They settled in Belton about 1866 where George entered the mercantile business and had an interest in a flour mill.

About the time George returned from the Civil War, where he attained the rank of Major in the Confederate Army, Martha McWhirter suffered something of a spiritual crisis. A brother and two of her children had died, which she interpreted as punishment from God.

Mrs. McWhirter prayed fervently and claimed to have a vision accompanied by an audible voice that told her she had been "sanctified," or filled with the Holy Spirit.

Members of her prayer group soon came to her with the news that they too had been sanctified. They became sisters in sanctification.

Ms. McWhirter's officially broke with the Methodist church in 1870 when the Methodists erected a building and proposed to organize a Methodist Sunday School to replace Belton's nonsectarian Union Sunday School, where her husband was a superintendent.

In time, the group completely cut itself off from all other organized church groups and became a religious entity all unto itself.

Part of the group's doctrine included the then unheard-of belief that men and women were equal in the eyes of God. One of Ms. McWhirter's divine revelations was that it was no longer a woman's duty to remain with a husband who bossed and controlled her, that God had made man and woman equal.

"We were to come out and be the 'peculiar people,'" she said.

The True Church Colony was open to men but most declined membership, probably because they took issue with the group's vows of celibacy with unsanctified mates.

Two brothers from Scotland, members of the Sanctificationist Church back home, joined the group. This displeased a group of Belton men, who took the brothers to the woods, stripped and flogged them. Lunacy charges were filed against the men when they refused to repent. The brothers won their case in court - something about the freedom of religion - but they never went back to True Church Colony again, which might have definitively proven their sanity.

The group evolved into a commune that held all wealth in common and which also doubled as something of a battered women's center, owing to the sometime violent reactions of husbands to their wives' newfound sanctity.

In its early days the group made ends meet by selling vegetables, chickens, butter and eggs. The business grew to include a laundry, a bakery, and a boarding house along with hotels in Belton and Waco.

The women's prosperity eventually brought them a measure of respect in Belton by virtue of the fact that they made a lot of money. Martha McWhirter even became the first woman to sit on the Belton's board of trade.

Mrs. McWhirter was the group's undisputed leader and she ruled with an iron fist and a will to match. The laws she set up were absolute and inflexible.

One of the laws stipulated that no sanctified woman could be the wife of an unsanctified husband, and visa versa. Women left their husbands in number high enough to draw attention from the community. Much of the community, especially the men, considered them little more than home wreckers.

Though the women seemed to have no qualms about leaving their husbands, neither did they protest when the husbands died and left them sizeable estates. In such a manner did the Sanctificationists inherit a homestead that became a headquarters for the colony.

Ms. McWhirter also received a sizeable inheritance from George, who left home after the couple's children had reached "the age of discretion." He spent the last years of his life in a room his wife fixed for him in his downtown office. The couple never spoke again. When he died in 1877, Ms. McWhirter said of her husband, "He believed in the sincerity of my religion and he always loved me."

At least one frustrated husband had his sanctified wife committed to an insane asylum but she was rescued by Mrs. McWhirter and received a $1,500 settlement from the state for being falsely committed - that freedom of religion thing again.

In 1900 the group sold or leased all its Texas property and went forth into the wider world, not to multiply but to look for a retirement home. They went north to the Great Lakes and south into Mexico but settled on Washington, D.C. where they bought a large house on Keenesaw Avenue.

The women were often seen out and about in the nation's capital, attending the theater and lectures and the galleries of Congress. They operated a farm in Maryland and a boarding house in Washington, D.C. The national press sometimes came calling. In spite of themselves, the women were almost celebrities.

Ms. McWhirter had believed for a long time that her days were numbered but she lived to be an old woman. "I used to worry much about death, but I think now that were are just in the dawn of the new dispensation when the Christ is to begin his reign of Peace on Earth," she said late in her life.

Martha McWhirter died in 1904 and Fannie Holtzclaw took over the as the commune's leader. The group dwindled away as its members died, the vow of celibacy doing away with the notion of any second generation Sanctificationists.

Martha Scheble, the last of the Sanctified Sisters, died on the Maryland farm in 1983 at the age of 101.

Family Members

-

![]()

Emma McWhirter Pond

1846–1918

-

Mary McWhirter

1849 – unknown

-

Ada McWhirter Haymond

1851–1898

-

![]()

John "Jack" McWhirter

1852–1881

-

Andrew McWhirter

1853–1853

-

![]()

Nancy McWhirter "Nannie" Davenport

1856–1935

-

George Merlin McWhirter II

1858–1858

-

George Merlin McWhirter III

1862–1866

-

Douglas McWhirter

1865–1865

-

![]()

Robert White McWhirter

1865–1956

-

William McWhirter

1868 – unknown

-

![]()

Samuel Seat McWhirter

1869–1901

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement