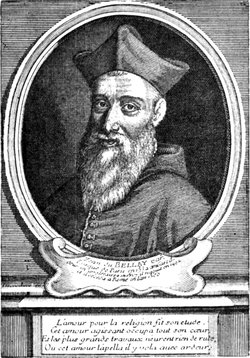

Bellay was born at Souday.

Subtle and clever, he was well fitted for a diplomatic career, and carried out several missions in England (1527–1534) and Rome (1534–1536). In 1535 he received his cardinal's hat; in 1536-1537 he was nominated "lieutenant-general" to the king at Paris and in the Tie de France, and was entrusted with the organization of the defence against the imperialists. When Guillaume du Bellay went to Piedmont, Jean was put in charge of the negotiations with the German Protestants, principally through the humanist Johann Sturm and the historian Johann Sleidan.

In the last years of the reign of Francis I, cardinal du Bellay was in favour with the duchesse d'Étampes, and received a number of benefices: the bishopric of Limoges (1541), archbishopric of Bordeaux (1544), bishopric of Le Mans (1546); but his influence in the council was supplanted by that of François de Tournon. Under Henry II, du Bellay, involved in the disgrace of all the servants of Francis I, was sent to Rome (1547). Following the death of Pope Paul III, he obtained eight votes in the conclave to elect the new pope.

After three quiet years passed in retirement in France (1550–1553), he was charged with a new mission to Pope Julius III and took with him to Rome his young cousin the poet Joachim du Bellay. He lived in Rome thenceforth in great state. In 1555 he was nominated bishop of Ostia and dean of the Sacred College, an appointment which was disapproved of by Henry II and brought him into fresh disgrace, lasting till his death in Rome on 16 February 1560.

Less resolute and reliable than his brother Guillaume, the cardinal had brilliant qualities, and an open and free mind. He was on the side of toleration and protected the reformers. Budaeus was his friend, François Rabelais his faithful secretary and doctor; men of letters, like Etienne Dolet, and the poet Salmon Macrin, were indebted to him for assistance. An orator and writer of Latin verse, he left three books of graceful Latin poems (printed with Salmon Macrin's Odes, 1546, by R Estienne), and some other compositions, including Francisci Francorum regis epistola apologetica (1542). His voluminous correspondence, mostly in manuscript, is remarkable for its verve and picturesque quality.

Bellay and François Rabelais [edit]

Rabelais traveled frequently to Rome with his friend Cardinal Jean du Bellay, and lived for a short time in Turin with du Bellay's brother, Guillaume, during which François I was his patron. Rabelais probably spent some time in hiding, threatened by being labeled a heretic. Only the protection of du Bellay saved Rabelais after the condemnation of his novel by the Sorbonne.

Rabelais was under scrutiny by the church due to "humanistic" nature of his writings. Rabelais's main work of this nature is the Gargantua and Pantagruel series, which contain a great deal of allegorical, suggestive messages.

Bellay was born at Souday.

Subtle and clever, he was well fitted for a diplomatic career, and carried out several missions in England (1527–1534) and Rome (1534–1536). In 1535 he received his cardinal's hat; in 1536-1537 he was nominated "lieutenant-general" to the king at Paris and in the Tie de France, and was entrusted with the organization of the defence against the imperialists. When Guillaume du Bellay went to Piedmont, Jean was put in charge of the negotiations with the German Protestants, principally through the humanist Johann Sturm and the historian Johann Sleidan.

In the last years of the reign of Francis I, cardinal du Bellay was in favour with the duchesse d'Étampes, and received a number of benefices: the bishopric of Limoges (1541), archbishopric of Bordeaux (1544), bishopric of Le Mans (1546); but his influence in the council was supplanted by that of François de Tournon. Under Henry II, du Bellay, involved in the disgrace of all the servants of Francis I, was sent to Rome (1547). Following the death of Pope Paul III, he obtained eight votes in the conclave to elect the new pope.

After three quiet years passed in retirement in France (1550–1553), he was charged with a new mission to Pope Julius III and took with him to Rome his young cousin the poet Joachim du Bellay. He lived in Rome thenceforth in great state. In 1555 he was nominated bishop of Ostia and dean of the Sacred College, an appointment which was disapproved of by Henry II and brought him into fresh disgrace, lasting till his death in Rome on 16 February 1560.

Less resolute and reliable than his brother Guillaume, the cardinal had brilliant qualities, and an open and free mind. He was on the side of toleration and protected the reformers. Budaeus was his friend, François Rabelais his faithful secretary and doctor; men of letters, like Etienne Dolet, and the poet Salmon Macrin, were indebted to him for assistance. An orator and writer of Latin verse, he left three books of graceful Latin poems (printed with Salmon Macrin's Odes, 1546, by R Estienne), and some other compositions, including Francisci Francorum regis epistola apologetica (1542). His voluminous correspondence, mostly in manuscript, is remarkable for its verve and picturesque quality.

Bellay and François Rabelais [edit]

Rabelais traveled frequently to Rome with his friend Cardinal Jean du Bellay, and lived for a short time in Turin with du Bellay's brother, Guillaume, during which François I was his patron. Rabelais probably spent some time in hiding, threatened by being labeled a heretic. Only the protection of du Bellay saved Rabelais after the condemnation of his novel by the Sorbonne.

Rabelais was under scrutiny by the church due to "humanistic" nature of his writings. Rabelais's main work of this nature is the Gargantua and Pantagruel series, which contain a great deal of allegorical, suggestive messages.

Advertisement

Advertisement