Second Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service ID: O-424962.

13th Pursuit Squadron

Entered the service from Nebraska.

Died: 1-Mar-42

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Awards: Purple Heart

~

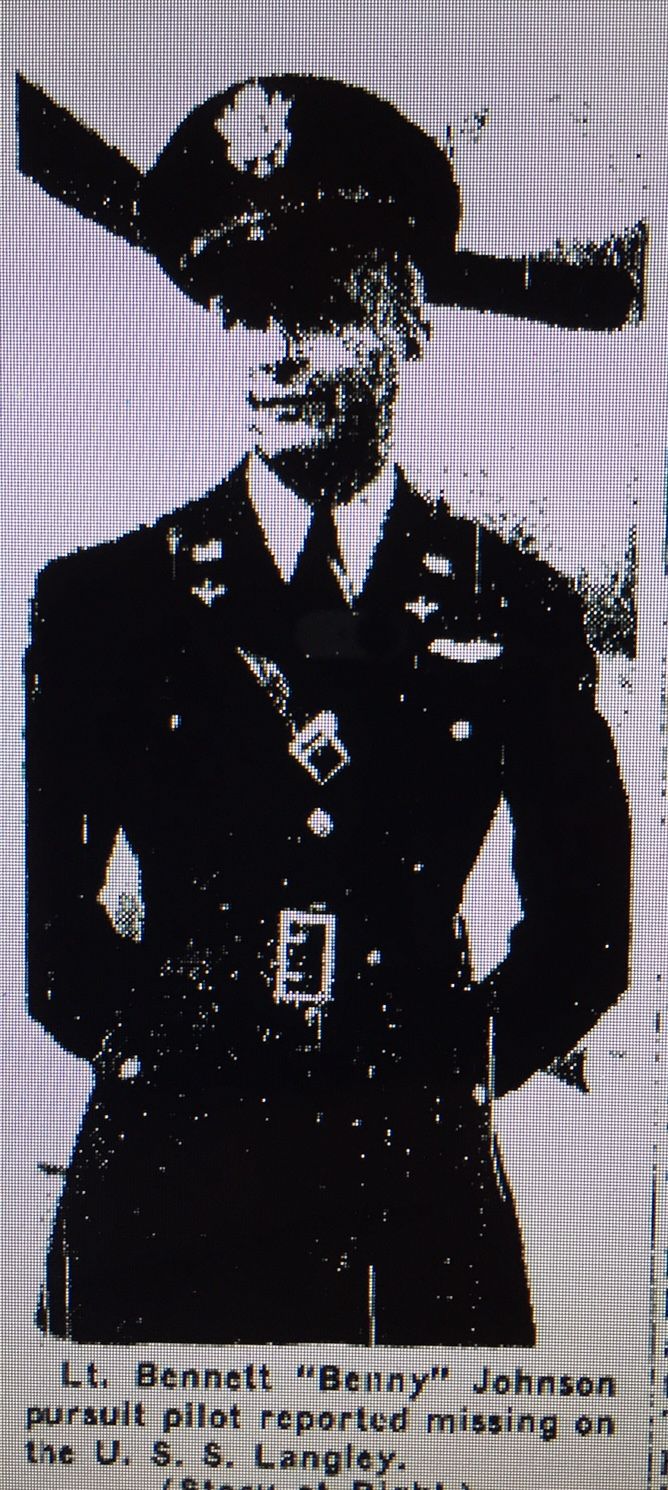

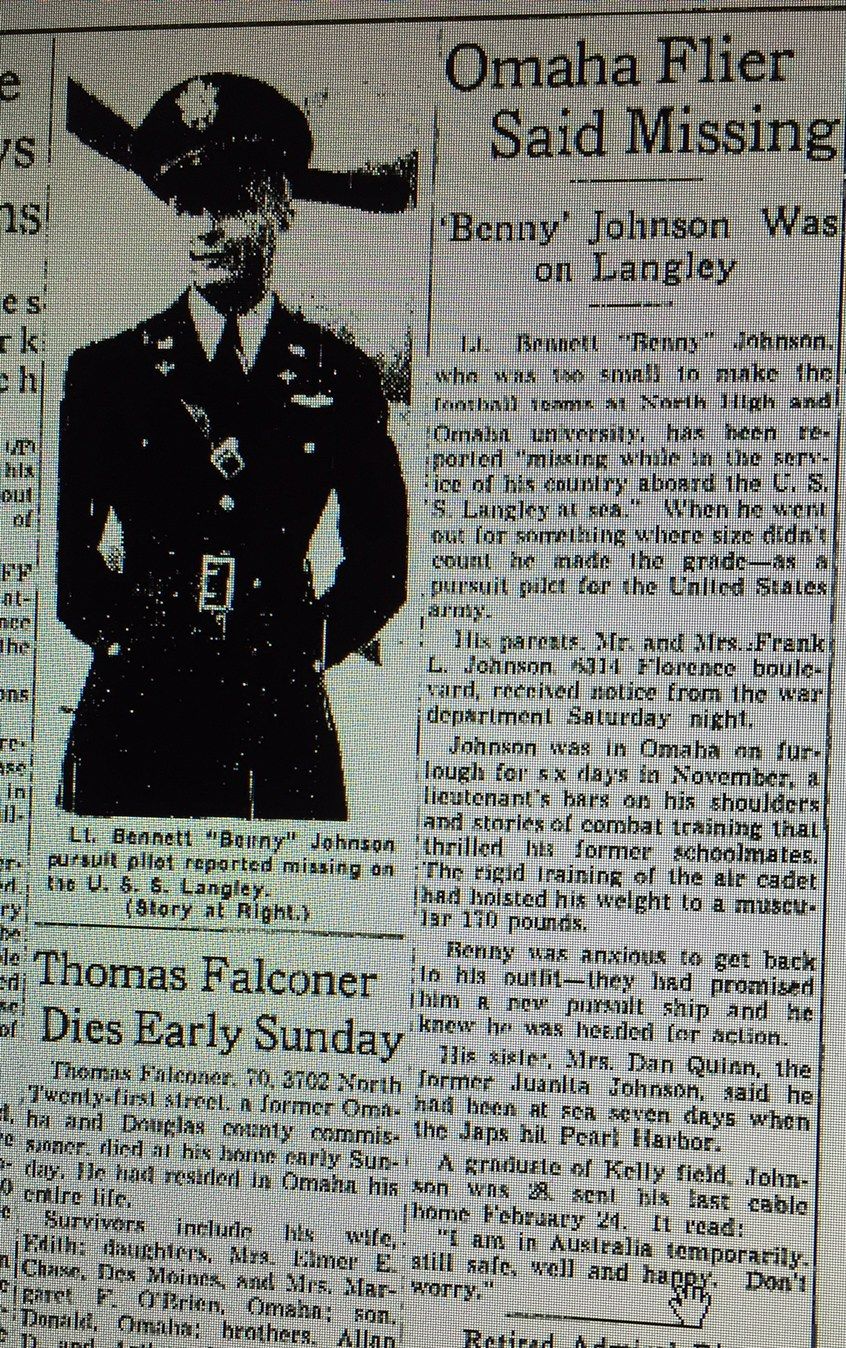

BENNETT LEE JOHNSON, also known as Benny, was born 24 March 1914 in Omaha, Douglas, Nebraska (NE). He was a son of Frank Leonard and Elizabeth Auda (Brown) Johnson who married 02 May 1909 in Omaha. Bennett's siblings were older sister Juanita Johnson Quinn (1910-1977), and younger brother, Frank Leonard Johnson Jr., (1924-1986), who served in the US Army during World War II. He died in a tractor accident at home in Olathe, KS in 1986.

Their father, Frank, a native of Wyoming, Iowa, was an accountant by profession. He began his career as an assistant purchasing agent and treasurer of the Burgess-Nash Company. Over time, he worked as a manager of the Douglas Truck Co. Later, he was associated with the bond redemption department of the Federal Reserve bank for four years. He was a member of the Douglas County tax appraisal board appointed to a six year term. He served on the Omaha school board from 1932-1940. It would seem that Frank was able to provide for his family during the tumultuous days of the Great Depression.

The Johnson children all graduated from high school. Bennett attended the North high school in Omaha. During his high school days, he was a member of the Student Council, a First Lieutenant of Co. G in the high school cadet reserve brigade, and he was on the Cheering team. Because he didn't weight enough, Benney wasn't able to play football. He was a member of the class of 189 graduates to receive their diplomas at commencement exercises held Thursday evening, 16 June 1932, at the school's auditorium.

That fall, Benney matriculated at the Municipal University of Omaha, or Muny as the school was affectionately known. He immediately applied for the cheering squad. He was one of the five selected to fill the vacancies on the team. It would seem that although he couldn't play on the football team, he certainly could lead the crowd to cheer them on. In addition, Benny was an avid participant in intramural basketball representing his fraternity, Theta Phi Delta. The Gateway newspaper of 08 Mar 1935 in Omaha called him the "Whirlwind" on the court.

In Sept of his senior year, camera-shy Bennett did not sit for his photograph in the 1936 Tomahawk yearbook according to a notation in it. On spring break in April 1936, Bennett traveled on vacation to Colorado, much to the envy of many of his fellow students. The Muny class of 1936 graduated on 4 Jun 1936. There were sixty-seven students who received their degrees and certificates at the commencement exercises (I was unable to find Bennett's name among those listed graduates in the Omaha newspapers.).

Sometime between June 1936 and 01 Apr 1940 (Date of US Census), Bennett moved to Los Angeles, California. The census of 1940 enumerated Bennett as being employed as an attendant at a gasoline filling station earning $1400.00 a year. He was also a college graduate and unmarried. On 16 Oct 1940, Bennett registered for the draft. His draft card recorded that he was employed by the Standard filling stations, Inc.; that he was born in Omaha, NE 24 Mar 1914 and his next of kin was F. L. Johnson (his father). This experience probably helped to thrust Bennett into his next decision which would be life altering.

On 27 Dec 1940, probably spurred on to seek a more adventuresome career infused with a sense of patriotism and urgency sparked by the draft registration, Bennett enlisted in the US Army Aviation Cadet program at Fort MacArthur, San Pedro, CA. His enlistment application stated he finished 4 yrs of college; lived in Los Angeles, was single w/o dependents and his birth year was 1914. It also stated his occupation – filling station attendant. Shortly after he completed his necessary paperwork, he was required to sit for an interview with the Air Corps examination board which accepted him into the cadet program.

On 05 Jan 41, Bennett was assigned to Army Aviation Cadet class 41-F. He began primary school at the airfield at Ontario, CA for the first of three 10 week training schools. In March 41, along with his training squadron friend, Robert August Kaiser of Oakland, CA, Bennett transferred to Goodfellow field in San Angelo, TX for his basic course. In June, the two friends transferred to Advanced flying training at Kelley field in San Antonio, TX. On 15 August 41, Bennett and Robert took the oath of office and accepted commissions as Second Lieutenants, US Army Air Corps Reserve. They were also presented with their Silver Wings of an Army Air Force pilot. Bennett's Army Service Number (ASN) was 0-424962. Robert's ASN was 0-424966 making Bennett the senior officer. After graduation, the two new pilots transferred to Hamilton field near San Francisco, California for additional training and assignment to the 21st squadron, 35th Pursuit Group. Hamilton was headquarters of the 35th Pursuit Group (PG).

An Omaha newspaper dated 11 Nov 41, reported that Lt Johnson had flown into Omaha from Hamilton Field, CA on a 7 day furlough to visit his parents. He arrived on 6 Nov 41 and had to return on 13 Nov. This would be the last time Benney would see his family.

Shortly after Lt Johnson returned from furlough he and Lt Kaiser received orders to report to the troop ship, USS Republic (AP-33) for transport to the Philippines (USAT Republic was taken over by the Navy and commissioned as USS Republic (AP-33) on 22 July 1941.)). She steamed out of San Francisco Bay under the Golden Gate Bridge the day after Thanksgiving, 21 Nov 1941 bound for Manila, Philippines via Pearl Harbor. Her passengers comprise some 2,666 Army Air Force personnel including forty-eight pursuit pilots of the 35th PG along with aircraft shipped disassembled in crates. After steaming a week, the Republic moored at Honolulu on 28 Nov 1941. Republic steamed out of Pearl Harbor on the 29th joining seven other ships and assumed the role of flagship for a convoy bound for the Philippines escorted by the heavy cruiser USS Pensacola (CA-24).

That convoy, generally known as the Pensacola Convoy (Army sources may use the term Republic convoy) was designated Task Group 15.5. Pensacola's convoy comprised the gunboat USS Niagara; the U.S. Navy transports USS Republic and USS Chaumont; the U.S. Army transport ships USAT Willard A. Holbrook (on board were thirty-nine newly graduated but unassigned pilots) and USAT Meigs; the U.S. merchant ships Admiral Halstead and Coast Farmer; and the Dutch merchant ship Bloemfontein on which were eighteen crated Curtiss P-40 fighter planes of the 35th PG (Interceptor). The convoy was intended to reinforce United States Army Forces Far East (USAFFE), created to defend the U.S. Commonwealth of the Philippines and commanded by Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

On 6 December the convoy crossed the equator celebrating the largest Army Shellback initiation up to that time. The following day the convoy commander received word that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor, the Philippines and Guam forcing the convoy to divert first to Suva in the Fiji Islands. Underway from Suva on 16 Dec, the convoy steamed to Brisbane, Australia where it arrived on 22 Dec 1941. The Republic began disembarking her passengers and unloading her cargo on the 23rd to a rousing welcome by many of the local Aussies.

The incoming US Army personnel were temporarily billeted at the Brisbane Ascot race track where 2-4 men tents were set-up. Living conditions for most were primitive at best. Some of the pilots ventured into Brisbane and managed to secure much more comfortable quarters. The primary focus for the army personnel, however, was unloading the crated P-40s in order to quickly begin assembling them. Once that was completed the urgency was to get pilots into the air and begin training so that planes and pilots could be transferred to the Philippines to reinforce USAFFE. Unfortunately, bureaucratic snafus, harsh environmental conditions, shortage of maintenance personnel, and wrong or no assembly parts conspired to impede the objective. In some case, pilots had to assemble their planes themselves. However, even after assembly, many air craft could not be flown because of a shortage of Prestone coolant for the engines. Stateside slipshod on-loading became the focus of blame. The Prestone had not been shipped with the aircraft. Fortunately, the Australian air corps and local supplies helped to mitigate the problem.

The 35th PG planned to begin training of its P-40 pilots on 2 Jan 42, however, there were far more rookie pilots than there were aircraft to fly. As January wore on training opportunities improved with the assembly of more aircraft. So to did the living quarters as most pilots moved to officer's quarters at Amberley Field. On Wednesday morning, 04 Feb 42, Johnson and Kaiser were among 24 P-40 pilots assigned to the newly created 3rd Pursuit Squadron (Provisional). Each was assigned a P-40 and told to be ready to fly north to Darwin then onward to Java. The next morning at 0830 the squadron took off in two divisions; first destination was Charelville for refueling. Then onward to Clonecurry where they refueled and spent the night. Early the next morning, 6 Feb 42, the 3rd took off again with a B-17 to guide them over the featureless and desolate landscape of the Outback of Australia. The squadron's penultimate stop was Daly Waters for refueling. According to the squadron's CO, "the landing strip looked as if had been 'cleared out of open country' "Several of the aircraft crashed while trying to land and were beyond repair. They were left behind.

Later that afternoon, Johnson and Kaiser and the remaining 19 P-40s were airborne again on their last leg to Darwin 360 miles north-northwest of Daly Waters. It was about 1940 hours that evening when the P-40s arrived at Darwin. They lost another plane in a landing mishap. That night the officers slept on the floor of the officers lounge while the enlisted support personnel of the 3rd stretched on the floor of the NCO mess hall. Several days later, Johnson and Kaiser, didn't fly to Java with the rest of the group. Instead, because they lacked the necessary flight experience, they were directed instead to return to Amberley Field and bring back P-40s for another transfer to Darwin and Java.

On 08 Feb 42, Kaiser and Johnson returned to Amberley. Upon arrival Lt Johnson transferred to the 13th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional) while Kaiser remained with the 3rd. The fact that Lt Kaiser was not assigned to the 13th with his friend, Lt Johnson, in all likelihood saved Kaiser's life. Lt Robert August Kaiser survived the war earning the Distinguished Flying Cross at Guadalcanal, married in 1943, had children and a successful career. He died in 1997.

Lt Johnson (13th PS) was one of a group of thirty-two P-40 Pursuit pilots from the 13th and 33rd Pursuit Squadrons (Provisional), 35th PG, ordered to Tjilatjap, Java to help provide fighter support to the Dutch and Allied forces attempting to repel the invading Japanese forces. On 22 Feb 1942, they embarked with 12 enlisted crew chiefs/Armorers on board the seaplane tender USS Langley (AV-3) at Fremantle, Australia. Hoisted on board the same day were thirty-two ready-to-fly P40s. The Langley, normally crewed by about 500 men, departed Fremantle later that day and steamed initially toward Burma and India, but Langley was soon redirected toward the port of Tjilatjap on Java where she was scheduled to arrive on 28 Feb.

At 0700 on the morning of 27 Feb, Langley rendezvoused with her anti-submarine destroyer escorts USS Whipple (DD-217) and USS Edsall (DD-219) about 100 miles from her destination. Two hours later, Langley and her escorts were spotted by an enemy reconnaissance plane. Shortly before 1200, sixteen (16) Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bombers of the Japanese 21st and 23rd Naval Air Flotillas and escorted by fifteen (15) A6M Reisen fighters began attacking Langley. She was about 70 miles from her destination. Langley was initially successful in dodging the falling ordinance, but eventually she was hit by multiple bombs sustaining fatal damage. At 1332, Langley's CO, CDR Robert P. McConnell, concluded that the ship was lost and ordered her abandoned. Within thirty minutes all of the survivors had been plucked from the sea by Whipple (308 officers and men including Lt Smith) and Edsall (177 officers and men).

At 1428, Whipple fired nine 4-inch rounds into Langley's hull. She then fired one torpedo (exploded) into the port side and then one into the starboard side of Langley. The last torpedo exploded causing a large fire. Because of the danger of another air attack, the two destroyers cleared the area, however, no one actually saw the Langley slide beneath the waves.

On 28 February, the two destroyers rendezvoused with the fuel replenishment ship USS Pecos (AO-6) off Flying Fish Cove, Christmas Island some 250 miles southwest of Tjilatjap. Prior to the arrival of Pecos, Whipple transferred 32 pilots/airmen, including Lt Smith, to Edsall. A sudden attack by land based Japanese bombers forced Edsall and the other ships to head for the open sea and postpone survivor transfers to Pecos.

The ships headed directly south into the Indian Ocean for the rest of 28 February in high winds and heavy seas. Early in the pre-dawn hours of 1 March, Whipple and Edsall transferred all the Langley survivors to Pecos. There were now close to 700 personnel aboard the oiler. Whipple then set off for Cocos Islands as protection for the tanker Belita sent to meet her there. The Pecos, carrying a large number of survivors was ordered to Australia. Edsall had retained 32 USAAF personnel from Langley needed to assemble and fly an additional 27 P-40E fighters shipped to Tjilatjap aboard the transport Sea Witch. Edsall was instructed to return these "fighter crews" to Tjilatjap. At 0830, she reversed course and headed back to the northeast for Java.

At noon that day, planes from Japanese aircraft carrier Soryu attacked Pecos and struck her again an hour later. Finally, in mid-afternoon, third and fourth strikes from carriers Hiryu and Akagi fatally wounded the Pecos. While under attack, Pecos radioed for help. After Pecos sank, Whipple returned to the scene intentionally arriving after dark. She eventually rescued 232 survivors. Many other survivors, although visible to crewmembers on board Whipple, had to be abandoned at sea because Whipple made sonar contact with what was believed to be several Japanese submarines. It was just too dangerous for her to remain in the area.

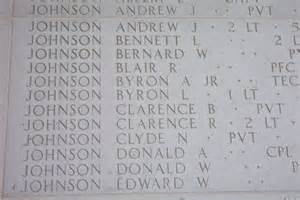

Edsall may have heard Pecos' call for help. Maybe she was following orders not to proceed to Java but steam south to Australia. In any case, Edsall reversed her northerly course and was never heard from again. Mr and Mrs Frank L. Johnson were informed by the war department that their son, Lt Bennett Lee Johnson, 27, a pursuit pilot attached to the U.S.S. Langley was reported missing by the Navy Department on 4 April 1942. His remains were unrecoverable. He was presumed dead on 25 Nov 1945.

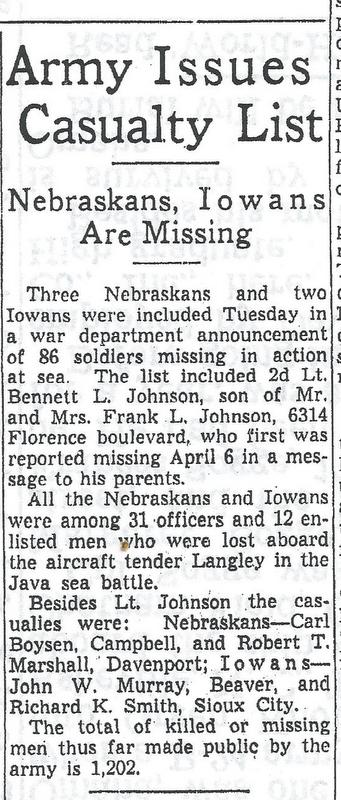

On 6 Apr 42, Mr and Mrs Frank L. Johnson of Omaha, NE., were notified by telegram that their son Lt Bennett L. Johnson was missing in the service of his country. On 11 August 42, The Johnsons were notified by the US War Department that 2d Lt Bennett L Johnson was among 31 officers and 12 enlisted men who were lost on board the aircraft tender Langley in the Java sea battle.

Lt Johnson was posthumously awarded the US Army Presidential Unit Citation, Purple Heart Medal, American Defense Service Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with one battle star and the World War II Victory Medal.

---------------------------------

The family also received a commemoration from then President Harry S. Truman. It reads: "In Grateful Memory of Second Lieutenant Bennett L. Johnson who died in the service of his country in the Pacific Area, 01 March 1942. He stands in the unbroken line of patriots who have dared to die that freedom might live and grow and increase it blessings. Freedom lives and through it he lives in a way that humbles the undertakings of most men.

//s//

Harry S Truman

President of the United States of America

------------------------------------

After WWII ended, an Allied War Crimes Tribunal was convened in Java in 1946. During the investigation it was learned from an eyewitness that allied POWs had been executed by the Japanese in early 1942. The witness provided the location of the massacre. The remains of six sailors were identified by their ID tags as members of the crew of USS Edsall (DD-219). Their remains were returned home for burial.

Because no known survivors lived to tell the Edsall''s story after the war, the details surrounding her sinking remained largely a mystery for more than a half century. Finally, after years of research, historians compiled a partial story of Edsall''s last hours, but it was not until Japanese records and eyewitnesses became available that the full story was revealed.

It was an epic battle of heroic proportion involving the aging Edsall and one of the world's strongest naval forces of its day. After Edsall reversed her course on 01 Mar 1942 and steamed away from Java, she stumbled upon Admiral Nagumo's battle force, Kido Butai, that had been prowling the Indian Ocean in search of enemy shipping. Unfortunately, Edsall was spotted first. She was initially misidentified as a Marblehead class light cruiser. IJN battleships Hiei and Kirishima and heavy cruisers Tone and Chikuma were directed to attack Edsall with surface gunfire. Edsall began evasive maneuvers, frustrating the Japanese for the next hour and half. Ducking in and out of her smoke screen and rain squalls, Edsall successfully avoided a fatal strike. However, because of the damage done previously to one of her propeller shafts, Edsall was unable to make top speed or maneuver fully. At one point Edsall turned and launched her torpedoes narrowly missing Chikuma. The Japanese ships fired 1400 rounds resulting in only one or two hits. The frustrated Admiral Nagumo called upon his carriers to finish off Edsall. She was attacked by dive-bombers from two Japanese carriers (Kaga, Soryu,) and possibly a third (Hiryu) before succumbing to their devastating attacks. The Edsall went down at 1731 hours, 430 miles south of Java.

It was learned in 1946 that at least six Edsall crew had survived the sinking. Many years later, however, Japanese eyewitnesses on board Chikuma confirmed that at least eight Edsall crewmen from a large number of survivors were fished out of the water and brought on board the Chikuma. The rest of the survivors were left to their fate in the water. Chikuma and the rest of the battle force arrived at Staring Bay anchorage, Celebes on 11 Mar 1942.

Three dozen POWs, at least 8 from the Edsall (possibly five more may have been Army Air Force personnel) and the remainder from a Dutch ship, were turned over to the Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces based at Kendari where they were executed by beheading on 24 Mar 1942 near Kendari II airfield, Netherland East Indies. Five of the six confirmed Edsall survivors who were executed are buried in a common grave at the Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery, Lemay, St. Louis, MO with five unknowns who were recovered near the Edsall five. Apparently several of the unknowns wore what looked like khaki uniforms. The grave of the sixth known Edsall crewman who survived and was executed was reburied at the request of his next of kin in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, HI.

--------------------------------------------

References

1). Barch, William H. Every Day a Nightmare: American pursuit pilots in the defense of Java, 1942-1943. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2010.

2). Cox, Jeffery R. Rising Sun, Falling Skies: The Disastrous Java Sea Campaign of World War II. Oxbury, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2014.

3). Kehn, Donald M. Jr. In the Highest Degree Tragic: The Sacrifice of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet in the East Indies during World War II. Potomac Book is an imprint of the University of Nebraska, 2017.

4). Kehn, Donald M. Jr. A Blue Sea of Blood: Deciphering the Mysterious Fate of the USS Edsall. Minneapolis, MN, Zenith Press, an imprint of MBI Publishing Company, 2008.

5). Messimer, Dwight R. Pawns of War: The Loss of the USS Langley and the USS Pecos. Annapolis, Maryland, Naval Institute Press, 1983.

6). Ancestry.com. Various US Census reports, 1900-1950. Online databases. Retrieved: 19 April – 23 April 2023.

7). Newspapers.com. Various news articles in Nebraska newspaper. On line databases. Retrieved: 19 April – 24 April 2023.

8). Ancestry.com. Tomahawk 1936, Municipal University of Omaha, Nebraska. Yearbooks database online. Retrieved: 20 April 2023.

---------------------------------------------

[Bio #416 composed on 22 Apr 2023 by Gerry Lawton (GML470)\

Military Hall of Honor ID# 144137

Second Lieutenant, U.S. Army Air Forces

Service ID: O-424962.

13th Pursuit Squadron

Entered the service from Nebraska.

Died: 1-Mar-42

Missing in Action or Buried at Sea

Awards: Purple Heart

~

BENNETT LEE JOHNSON, also known as Benny, was born 24 March 1914 in Omaha, Douglas, Nebraska (NE). He was a son of Frank Leonard and Elizabeth Auda (Brown) Johnson who married 02 May 1909 in Omaha. Bennett's siblings were older sister Juanita Johnson Quinn (1910-1977), and younger brother, Frank Leonard Johnson Jr., (1924-1986), who served in the US Army during World War II. He died in a tractor accident at home in Olathe, KS in 1986.

Their father, Frank, a native of Wyoming, Iowa, was an accountant by profession. He began his career as an assistant purchasing agent and treasurer of the Burgess-Nash Company. Over time, he worked as a manager of the Douglas Truck Co. Later, he was associated with the bond redemption department of the Federal Reserve bank for four years. He was a member of the Douglas County tax appraisal board appointed to a six year term. He served on the Omaha school board from 1932-1940. It would seem that Frank was able to provide for his family during the tumultuous days of the Great Depression.

The Johnson children all graduated from high school. Bennett attended the North high school in Omaha. During his high school days, he was a member of the Student Council, a First Lieutenant of Co. G in the high school cadet reserve brigade, and he was on the Cheering team. Because he didn't weight enough, Benney wasn't able to play football. He was a member of the class of 189 graduates to receive their diplomas at commencement exercises held Thursday evening, 16 June 1932, at the school's auditorium.

That fall, Benney matriculated at the Municipal University of Omaha, or Muny as the school was affectionately known. He immediately applied for the cheering squad. He was one of the five selected to fill the vacancies on the team. It would seem that although he couldn't play on the football team, he certainly could lead the crowd to cheer them on. In addition, Benny was an avid participant in intramural basketball representing his fraternity, Theta Phi Delta. The Gateway newspaper of 08 Mar 1935 in Omaha called him the "Whirlwind" on the court.

In Sept of his senior year, camera-shy Bennett did not sit for his photograph in the 1936 Tomahawk yearbook according to a notation in it. On spring break in April 1936, Bennett traveled on vacation to Colorado, much to the envy of many of his fellow students. The Muny class of 1936 graduated on 4 Jun 1936. There were sixty-seven students who received their degrees and certificates at the commencement exercises (I was unable to find Bennett's name among those listed graduates in the Omaha newspapers.).

Sometime between June 1936 and 01 Apr 1940 (Date of US Census), Bennett moved to Los Angeles, California. The census of 1940 enumerated Bennett as being employed as an attendant at a gasoline filling station earning $1400.00 a year. He was also a college graduate and unmarried. On 16 Oct 1940, Bennett registered for the draft. His draft card recorded that he was employed by the Standard filling stations, Inc.; that he was born in Omaha, NE 24 Mar 1914 and his next of kin was F. L. Johnson (his father). This experience probably helped to thrust Bennett into his next decision which would be life altering.

On 27 Dec 1940, probably spurred on to seek a more adventuresome career infused with a sense of patriotism and urgency sparked by the draft registration, Bennett enlisted in the US Army Aviation Cadet program at Fort MacArthur, San Pedro, CA. His enlistment application stated he finished 4 yrs of college; lived in Los Angeles, was single w/o dependents and his birth year was 1914. It also stated his occupation – filling station attendant. Shortly after he completed his necessary paperwork, he was required to sit for an interview with the Air Corps examination board which accepted him into the cadet program.

On 05 Jan 41, Bennett was assigned to Army Aviation Cadet class 41-F. He began primary school at the airfield at Ontario, CA for the first of three 10 week training schools. In March 41, along with his training squadron friend, Robert August Kaiser of Oakland, CA, Bennett transferred to Goodfellow field in San Angelo, TX for his basic course. In June, the two friends transferred to Advanced flying training at Kelley field in San Antonio, TX. On 15 August 41, Bennett and Robert took the oath of office and accepted commissions as Second Lieutenants, US Army Air Corps Reserve. They were also presented with their Silver Wings of an Army Air Force pilot. Bennett's Army Service Number (ASN) was 0-424962. Robert's ASN was 0-424966 making Bennett the senior officer. After graduation, the two new pilots transferred to Hamilton field near San Francisco, California for additional training and assignment to the 21st squadron, 35th Pursuit Group. Hamilton was headquarters of the 35th Pursuit Group (PG).

An Omaha newspaper dated 11 Nov 41, reported that Lt Johnson had flown into Omaha from Hamilton Field, CA on a 7 day furlough to visit his parents. He arrived on 6 Nov 41 and had to return on 13 Nov. This would be the last time Benney would see his family.

Shortly after Lt Johnson returned from furlough he and Lt Kaiser received orders to report to the troop ship, USS Republic (AP-33) for transport to the Philippines (USAT Republic was taken over by the Navy and commissioned as USS Republic (AP-33) on 22 July 1941.)). She steamed out of San Francisco Bay under the Golden Gate Bridge the day after Thanksgiving, 21 Nov 1941 bound for Manila, Philippines via Pearl Harbor. Her passengers comprise some 2,666 Army Air Force personnel including forty-eight pursuit pilots of the 35th PG along with aircraft shipped disassembled in crates. After steaming a week, the Republic moored at Honolulu on 28 Nov 1941. Republic steamed out of Pearl Harbor on the 29th joining seven other ships and assumed the role of flagship for a convoy bound for the Philippines escorted by the heavy cruiser USS Pensacola (CA-24).

That convoy, generally known as the Pensacola Convoy (Army sources may use the term Republic convoy) was designated Task Group 15.5. Pensacola's convoy comprised the gunboat USS Niagara; the U.S. Navy transports USS Republic and USS Chaumont; the U.S. Army transport ships USAT Willard A. Holbrook (on board were thirty-nine newly graduated but unassigned pilots) and USAT Meigs; the U.S. merchant ships Admiral Halstead and Coast Farmer; and the Dutch merchant ship Bloemfontein on which were eighteen crated Curtiss P-40 fighter planes of the 35th PG (Interceptor). The convoy was intended to reinforce United States Army Forces Far East (USAFFE), created to defend the U.S. Commonwealth of the Philippines and commanded by Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

On 6 December the convoy crossed the equator celebrating the largest Army Shellback initiation up to that time. The following day the convoy commander received word that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor, the Philippines and Guam forcing the convoy to divert first to Suva in the Fiji Islands. Underway from Suva on 16 Dec, the convoy steamed to Brisbane, Australia where it arrived on 22 Dec 1941. The Republic began disembarking her passengers and unloading her cargo on the 23rd to a rousing welcome by many of the local Aussies.

The incoming US Army personnel were temporarily billeted at the Brisbane Ascot race track where 2-4 men tents were set-up. Living conditions for most were primitive at best. Some of the pilots ventured into Brisbane and managed to secure much more comfortable quarters. The primary focus for the army personnel, however, was unloading the crated P-40s in order to quickly begin assembling them. Once that was completed the urgency was to get pilots into the air and begin training so that planes and pilots could be transferred to the Philippines to reinforce USAFFE. Unfortunately, bureaucratic snafus, harsh environmental conditions, shortage of maintenance personnel, and wrong or no assembly parts conspired to impede the objective. In some case, pilots had to assemble their planes themselves. However, even after assembly, many air craft could not be flown because of a shortage of Prestone coolant for the engines. Stateside slipshod on-loading became the focus of blame. The Prestone had not been shipped with the aircraft. Fortunately, the Australian air corps and local supplies helped to mitigate the problem.

The 35th PG planned to begin training of its P-40 pilots on 2 Jan 42, however, there were far more rookie pilots than there were aircraft to fly. As January wore on training opportunities improved with the assembly of more aircraft. So to did the living quarters as most pilots moved to officer's quarters at Amberley Field. On Wednesday morning, 04 Feb 42, Johnson and Kaiser were among 24 P-40 pilots assigned to the newly created 3rd Pursuit Squadron (Provisional). Each was assigned a P-40 and told to be ready to fly north to Darwin then onward to Java. The next morning at 0830 the squadron took off in two divisions; first destination was Charelville for refueling. Then onward to Clonecurry where they refueled and spent the night. Early the next morning, 6 Feb 42, the 3rd took off again with a B-17 to guide them over the featureless and desolate landscape of the Outback of Australia. The squadron's penultimate stop was Daly Waters for refueling. According to the squadron's CO, "the landing strip looked as if had been 'cleared out of open country' "Several of the aircraft crashed while trying to land and were beyond repair. They were left behind.

Later that afternoon, Johnson and Kaiser and the remaining 19 P-40s were airborne again on their last leg to Darwin 360 miles north-northwest of Daly Waters. It was about 1940 hours that evening when the P-40s arrived at Darwin. They lost another plane in a landing mishap. That night the officers slept on the floor of the officers lounge while the enlisted support personnel of the 3rd stretched on the floor of the NCO mess hall. Several days later, Johnson and Kaiser, didn't fly to Java with the rest of the group. Instead, because they lacked the necessary flight experience, they were directed instead to return to Amberley Field and bring back P-40s for another transfer to Darwin and Java.

On 08 Feb 42, Kaiser and Johnson returned to Amberley. Upon arrival Lt Johnson transferred to the 13th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional) while Kaiser remained with the 3rd. The fact that Lt Kaiser was not assigned to the 13th with his friend, Lt Johnson, in all likelihood saved Kaiser's life. Lt Robert August Kaiser survived the war earning the Distinguished Flying Cross at Guadalcanal, married in 1943, had children and a successful career. He died in 1997.

Lt Johnson (13th PS) was one of a group of thirty-two P-40 Pursuit pilots from the 13th and 33rd Pursuit Squadrons (Provisional), 35th PG, ordered to Tjilatjap, Java to help provide fighter support to the Dutch and Allied forces attempting to repel the invading Japanese forces. On 22 Feb 1942, they embarked with 12 enlisted crew chiefs/Armorers on board the seaplane tender USS Langley (AV-3) at Fremantle, Australia. Hoisted on board the same day were thirty-two ready-to-fly P40s. The Langley, normally crewed by about 500 men, departed Fremantle later that day and steamed initially toward Burma and India, but Langley was soon redirected toward the port of Tjilatjap on Java where she was scheduled to arrive on 28 Feb.

At 0700 on the morning of 27 Feb, Langley rendezvoused with her anti-submarine destroyer escorts USS Whipple (DD-217) and USS Edsall (DD-219) about 100 miles from her destination. Two hours later, Langley and her escorts were spotted by an enemy reconnaissance plane. Shortly before 1200, sixteen (16) Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bombers of the Japanese 21st and 23rd Naval Air Flotillas and escorted by fifteen (15) A6M Reisen fighters began attacking Langley. She was about 70 miles from her destination. Langley was initially successful in dodging the falling ordinance, but eventually she was hit by multiple bombs sustaining fatal damage. At 1332, Langley's CO, CDR Robert P. McConnell, concluded that the ship was lost and ordered her abandoned. Within thirty minutes all of the survivors had been plucked from the sea by Whipple (308 officers and men including Lt Smith) and Edsall (177 officers and men).

At 1428, Whipple fired nine 4-inch rounds into Langley's hull. She then fired one torpedo (exploded) into the port side and then one into the starboard side of Langley. The last torpedo exploded causing a large fire. Because of the danger of another air attack, the two destroyers cleared the area, however, no one actually saw the Langley slide beneath the waves.

On 28 February, the two destroyers rendezvoused with the fuel replenishment ship USS Pecos (AO-6) off Flying Fish Cove, Christmas Island some 250 miles southwest of Tjilatjap. Prior to the arrival of Pecos, Whipple transferred 32 pilots/airmen, including Lt Smith, to Edsall. A sudden attack by land based Japanese bombers forced Edsall and the other ships to head for the open sea and postpone survivor transfers to Pecos.

The ships headed directly south into the Indian Ocean for the rest of 28 February in high winds and heavy seas. Early in the pre-dawn hours of 1 March, Whipple and Edsall transferred all the Langley survivors to Pecos. There were now close to 700 personnel aboard the oiler. Whipple then set off for Cocos Islands as protection for the tanker Belita sent to meet her there. The Pecos, carrying a large number of survivors was ordered to Australia. Edsall had retained 32 USAAF personnel from Langley needed to assemble and fly an additional 27 P-40E fighters shipped to Tjilatjap aboard the transport Sea Witch. Edsall was instructed to return these "fighter crews" to Tjilatjap. At 0830, she reversed course and headed back to the northeast for Java.

At noon that day, planes from Japanese aircraft carrier Soryu attacked Pecos and struck her again an hour later. Finally, in mid-afternoon, third and fourth strikes from carriers Hiryu and Akagi fatally wounded the Pecos. While under attack, Pecos radioed for help. After Pecos sank, Whipple returned to the scene intentionally arriving after dark. She eventually rescued 232 survivors. Many other survivors, although visible to crewmembers on board Whipple, had to be abandoned at sea because Whipple made sonar contact with what was believed to be several Japanese submarines. It was just too dangerous for her to remain in the area.

Edsall may have heard Pecos' call for help. Maybe she was following orders not to proceed to Java but steam south to Australia. In any case, Edsall reversed her northerly course and was never heard from again. Mr and Mrs Frank L. Johnson were informed by the war department that their son, Lt Bennett Lee Johnson, 27, a pursuit pilot attached to the U.S.S. Langley was reported missing by the Navy Department on 4 April 1942. His remains were unrecoverable. He was presumed dead on 25 Nov 1945.

On 6 Apr 42, Mr and Mrs Frank L. Johnson of Omaha, NE., were notified by telegram that their son Lt Bennett L. Johnson was missing in the service of his country. On 11 August 42, The Johnsons were notified by the US War Department that 2d Lt Bennett L Johnson was among 31 officers and 12 enlisted men who were lost on board the aircraft tender Langley in the Java sea battle.

Lt Johnson was posthumously awarded the US Army Presidential Unit Citation, Purple Heart Medal, American Defense Service Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with one battle star and the World War II Victory Medal.

---------------------------------

The family also received a commemoration from then President Harry S. Truman. It reads: "In Grateful Memory of Second Lieutenant Bennett L. Johnson who died in the service of his country in the Pacific Area, 01 March 1942. He stands in the unbroken line of patriots who have dared to die that freedom might live and grow and increase it blessings. Freedom lives and through it he lives in a way that humbles the undertakings of most men.

//s//

Harry S Truman

President of the United States of America

------------------------------------

After WWII ended, an Allied War Crimes Tribunal was convened in Java in 1946. During the investigation it was learned from an eyewitness that allied POWs had been executed by the Japanese in early 1942. The witness provided the location of the massacre. The remains of six sailors were identified by their ID tags as members of the crew of USS Edsall (DD-219). Their remains were returned home for burial.

Because no known survivors lived to tell the Edsall''s story after the war, the details surrounding her sinking remained largely a mystery for more than a half century. Finally, after years of research, historians compiled a partial story of Edsall''s last hours, but it was not until Japanese records and eyewitnesses became available that the full story was revealed.

It was an epic battle of heroic proportion involving the aging Edsall and one of the world's strongest naval forces of its day. After Edsall reversed her course on 01 Mar 1942 and steamed away from Java, she stumbled upon Admiral Nagumo's battle force, Kido Butai, that had been prowling the Indian Ocean in search of enemy shipping. Unfortunately, Edsall was spotted first. She was initially misidentified as a Marblehead class light cruiser. IJN battleships Hiei and Kirishima and heavy cruisers Tone and Chikuma were directed to attack Edsall with surface gunfire. Edsall began evasive maneuvers, frustrating the Japanese for the next hour and half. Ducking in and out of her smoke screen and rain squalls, Edsall successfully avoided a fatal strike. However, because of the damage done previously to one of her propeller shafts, Edsall was unable to make top speed or maneuver fully. At one point Edsall turned and launched her torpedoes narrowly missing Chikuma. The Japanese ships fired 1400 rounds resulting in only one or two hits. The frustrated Admiral Nagumo called upon his carriers to finish off Edsall. She was attacked by dive-bombers from two Japanese carriers (Kaga, Soryu,) and possibly a third (Hiryu) before succumbing to their devastating attacks. The Edsall went down at 1731 hours, 430 miles south of Java.

It was learned in 1946 that at least six Edsall crew had survived the sinking. Many years later, however, Japanese eyewitnesses on board Chikuma confirmed that at least eight Edsall crewmen from a large number of survivors were fished out of the water and brought on board the Chikuma. The rest of the survivors were left to their fate in the water. Chikuma and the rest of the battle force arrived at Staring Bay anchorage, Celebes on 11 Mar 1942.

Three dozen POWs, at least 8 from the Edsall (possibly five more may have been Army Air Force personnel) and the remainder from a Dutch ship, were turned over to the Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces based at Kendari where they were executed by beheading on 24 Mar 1942 near Kendari II airfield, Netherland East Indies. Five of the six confirmed Edsall survivors who were executed are buried in a common grave at the Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery, Lemay, St. Louis, MO with five unknowns who were recovered near the Edsall five. Apparently several of the unknowns wore what looked like khaki uniforms. The grave of the sixth known Edsall crewman who survived and was executed was reburied at the request of his next of kin in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, HI.

--------------------------------------------

References

1). Barch, William H. Every Day a Nightmare: American pursuit pilots in the defense of Java, 1942-1943. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2010.

2). Cox, Jeffery R. Rising Sun, Falling Skies: The Disastrous Java Sea Campaign of World War II. Oxbury, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2014.

3). Kehn, Donald M. Jr. In the Highest Degree Tragic: The Sacrifice of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet in the East Indies during World War II. Potomac Book is an imprint of the University of Nebraska, 2017.

4). Kehn, Donald M. Jr. A Blue Sea of Blood: Deciphering the Mysterious Fate of the USS Edsall. Minneapolis, MN, Zenith Press, an imprint of MBI Publishing Company, 2008.

5). Messimer, Dwight R. Pawns of War: The Loss of the USS Langley and the USS Pecos. Annapolis, Maryland, Naval Institute Press, 1983.

6). Ancestry.com. Various US Census reports, 1900-1950. Online databases. Retrieved: 19 April – 23 April 2023.

7). Newspapers.com. Various news articles in Nebraska newspaper. On line databases. Retrieved: 19 April – 24 April 2023.

8). Ancestry.com. Tomahawk 1936, Municipal University of Omaha, Nebraska. Yearbooks database online. Retrieved: 20 April 2023.

---------------------------------------------

[Bio #416 composed on 22 Apr 2023 by Gerry Lawton (GML470)\

Military Hall of Honor ID# 144137