Jerry Abernathy graduated from college in 1967 and went right into teaching in the St. Louis Public Schools. It was crowded — he was one of 4,000 teachers and 115,000 students, the highest number ever enrolled in St. Louis schools.

With whites moving to the suburbs, the city had a declining tax base. It was becoming smaller, blacker and poorer.

Inside the schools, teachers argued that they couldn't manage classrooms crowded with as many as 50 students. Teachers who barely earned $7,000 lacked health insurance. When the School Board repeatedly ignored them, teachers demanded the right to collective bargaining.

By 1973, Mr. Abernathy was a labor leader. He helped spearhead the first teachers' strike in St. Louis. He defied a state ban on strikes and a judge who threatened to send him to jail. He helped get better pay and working conditions and ushered in a new teacher militancy that lasted for years.

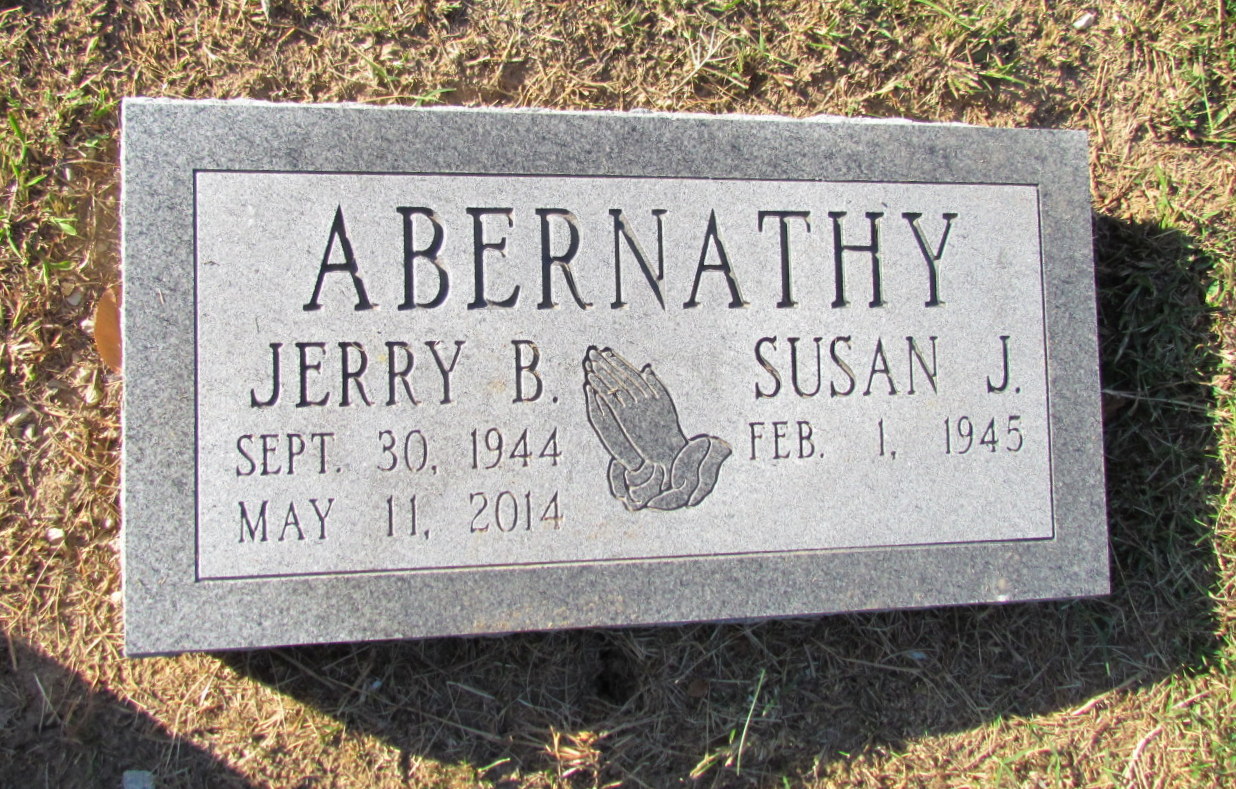

Mr. Abernathy died Sunday (May 11, 2014) at Delmar Gardens in Chesterfield. He was 69 and had lived in Innsbrook in Warren County. The cause was cancer, his wife, Susan Abernathy, said Tuesday.

By Michael D. Sorkin, Post Dispatch reporter

Son of Glover Eugene and Marcella A. Stone Abernathy

Mr. Abernathy was no radical. He didn't want a strike, according to Daniel Gonzales, a historian who studied the strike of 1973. Mr. Abernathy simply saw no alternative for teachers or students.

Jerry Brooks Abernathy grew up in a conservative, blue-collar family in a predominantly white neighborhood in south St. Louis. His father was a maintenance worker for the Ford Motor Co. Like his father, Mr. Abernathy became a Republican; Susan Abernathy remembers her husband voting for just one Democrat during their 39 years of marriage.

Mr. Abernathy graduated from Roosevelt High School in 1962. After graduating from what is now Harris-Stowe State University, he had his pick of three jobs in the St. Louis schools.

He joined the St. Louis Teachers Association, an affiliate of the National Education Association, at the urging of a professor. He was attracted to the group's educational advocacy. He did not view it as a trade union.

The other teachers organization was the more militant St. Louis Teachers Union, an affiliate of the American Federation of Teachers. Its leader was Demonsthenes DuBose, who grew up in a predominantly middle-class black neighborhood in north St. Louis.

The two rival unions joined forces in 1973 when the School Board again said there was no money for teacher raises.

After months in which the teachers felt they weren't being valued or listened to, Mr. Abernathy went on TV and said the teachers were going on strike.

"That's how he got himself in trouble," Susan Abernathy recalled.

Striking was — and is — illegal for teachers and other public employees in Missouri, according to court decisions. School Board members got a restraining order to stop Mr. Abernathy.

They hired photographers and private detectives to attend meetings and intimidate the teachers, according to an analysis of the strike.

When the two unions voted to strike, a St. Louis Circuit Court judge held Mr. Abernathy and others in contempt. The judge fined Mr. Abernathy $350 a day — a hefty sum for a teacher in 1973. Some teachers fled to Illinois to avoid being fined.

Soon after the teachers began picketing, all 10 high schools in the city were closed. By the third day, all city schools were closed. Of 4,170 St. Louis teachers, 3,500 joined the strike.

At first, School Board members wouldn't budge. Daniel L. Schlafly and other members of the so-called "Blue Ribbon" School Board had been elected to root out corruption in the district. They were suspicious of the unions and didn't want any dealings with them.

That was before the lack of classroom supervision resulted in vandalism by students, including throwing desks out of windows. Parents feared their children would have to spend the summer in school.

With pressure mounting, Schlafly went to the city's Board of Aldermen, which gave the schools $1 million on the condition that both sides settle the strike "NOW."

Teachers across the country sent money to pay for the fines Mr. Abernathy was accruing daily. In the end, the judge relented; instead of jail, he ordered Mr. Abernathy to perform two summers of unpaid work at a facility for boys.

Susan Abernathy met her husband at a union organizing meeting. Although they were both teachers, she described their marriage in 1975 as improbable.

He was a Republican, she was a Democrat. He belonged to the United Church of Christ; she was Catholic. On top of that, she crossed his picket lines and tore up her union card. They started dating after the strike, and she rejoined the union. (Late in life, Mr. Abernathy converted to Catholicism.)

The 29-day strike resulted in moderate gains in benefits and pay, said Gonzales, the historian. More importantly, the School Board learned that the teachers could strike. And the teachers learned they had that power, Gonzales added.

In 1979, there was a second strike that won a bigger bump in salaries. In 2007, the Missouri Supreme Court ruled that public employees have a right to engage in collective bargaining. Strikes remain illegal.

As for Mr. Abernathy, "I don't think he wanted to be a social radical," Gonzales said. "He did what he thought he needed to."

Mr. Abernathy retired from the school district in 2000. He volunteered, played poker and traveled. He and his wife were getting ready for a Caribbean cruise in February when he was diagnosed with esophageal cancer that quickly spread, his wife said.

The funeral Mass will be celebrated at 10 a.m. today at Holy Rosary Catholic Church, 724 East Booneslick Road in Warrenton. Burial will follow at 2 p.m. at St. Marcus Cemetery, 7901 Gravois Road.

Survivors, in addition to his wife, include a son, Jeffrey B. Abernathy of St. Louis; a daughter, Rebecca Abernathy of St. Louis; a sister, Norma Smith of Ellisville; and a granddaughter.

By Michael D. Sorkin, Post Dispatch reporter

Son of Glover Eugene and Marcella A. Stone Abernathy

Jerry Abernathy graduated from college in 1967 and went right into teaching in the St. Louis Public Schools. It was crowded — he was one of 4,000 teachers and 115,000 students, the highest number ever enrolled in St. Louis schools.

With whites moving to the suburbs, the city had a declining tax base. It was becoming smaller, blacker and poorer.

Inside the schools, teachers argued that they couldn't manage classrooms crowded with as many as 50 students. Teachers who barely earned $7,000 lacked health insurance. When the School Board repeatedly ignored them, teachers demanded the right to collective bargaining.

By 1973, Mr. Abernathy was a labor leader. He helped spearhead the first teachers' strike in St. Louis. He defied a state ban on strikes and a judge who threatened to send him to jail. He helped get better pay and working conditions and ushered in a new teacher militancy that lasted for years.

Mr. Abernathy died Sunday (May 11, 2014) at Delmar Gardens in Chesterfield. He was 69 and had lived in Innsbrook in Warren County. The cause was cancer, his wife, Susan Abernathy, said Tuesday.

By Michael D. Sorkin, Post Dispatch reporter

Son of Glover Eugene and Marcella A. Stone Abernathy

Mr. Abernathy was no radical. He didn't want a strike, according to Daniel Gonzales, a historian who studied the strike of 1973. Mr. Abernathy simply saw no alternative for teachers or students.

Jerry Brooks Abernathy grew up in a conservative, blue-collar family in a predominantly white neighborhood in south St. Louis. His father was a maintenance worker for the Ford Motor Co. Like his father, Mr. Abernathy became a Republican; Susan Abernathy remembers her husband voting for just one Democrat during their 39 years of marriage.

Mr. Abernathy graduated from Roosevelt High School in 1962. After graduating from what is now Harris-Stowe State University, he had his pick of three jobs in the St. Louis schools.

He joined the St. Louis Teachers Association, an affiliate of the National Education Association, at the urging of a professor. He was attracted to the group's educational advocacy. He did not view it as a trade union.

The other teachers organization was the more militant St. Louis Teachers Union, an affiliate of the American Federation of Teachers. Its leader was Demonsthenes DuBose, who grew up in a predominantly middle-class black neighborhood in north St. Louis.

The two rival unions joined forces in 1973 when the School Board again said there was no money for teacher raises.

After months in which the teachers felt they weren't being valued or listened to, Mr. Abernathy went on TV and said the teachers were going on strike.

"That's how he got himself in trouble," Susan Abernathy recalled.

Striking was — and is — illegal for teachers and other public employees in Missouri, according to court decisions. School Board members got a restraining order to stop Mr. Abernathy.

They hired photographers and private detectives to attend meetings and intimidate the teachers, according to an analysis of the strike.

When the two unions voted to strike, a St. Louis Circuit Court judge held Mr. Abernathy and others in contempt. The judge fined Mr. Abernathy $350 a day — a hefty sum for a teacher in 1973. Some teachers fled to Illinois to avoid being fined.

Soon after the teachers began picketing, all 10 high schools in the city were closed. By the third day, all city schools were closed. Of 4,170 St. Louis teachers, 3,500 joined the strike.

At first, School Board members wouldn't budge. Daniel L. Schlafly and other members of the so-called "Blue Ribbon" School Board had been elected to root out corruption in the district. They were suspicious of the unions and didn't want any dealings with them.

That was before the lack of classroom supervision resulted in vandalism by students, including throwing desks out of windows. Parents feared their children would have to spend the summer in school.

With pressure mounting, Schlafly went to the city's Board of Aldermen, which gave the schools $1 million on the condition that both sides settle the strike "NOW."

Teachers across the country sent money to pay for the fines Mr. Abernathy was accruing daily. In the end, the judge relented; instead of jail, he ordered Mr. Abernathy to perform two summers of unpaid work at a facility for boys.

Susan Abernathy met her husband at a union organizing meeting. Although they were both teachers, she described their marriage in 1975 as improbable.

He was a Republican, she was a Democrat. He belonged to the United Church of Christ; she was Catholic. On top of that, she crossed his picket lines and tore up her union card. They started dating after the strike, and she rejoined the union. (Late in life, Mr. Abernathy converted to Catholicism.)

The 29-day strike resulted in moderate gains in benefits and pay, said Gonzales, the historian. More importantly, the School Board learned that the teachers could strike. And the teachers learned they had that power, Gonzales added.

In 1979, there was a second strike that won a bigger bump in salaries. In 2007, the Missouri Supreme Court ruled that public employees have a right to engage in collective bargaining. Strikes remain illegal.

As for Mr. Abernathy, "I don't think he wanted to be a social radical," Gonzales said. "He did what he thought he needed to."

Mr. Abernathy retired from the school district in 2000. He volunteered, played poker and traveled. He and his wife were getting ready for a Caribbean cruise in February when he was diagnosed with esophageal cancer that quickly spread, his wife said.

The funeral Mass will be celebrated at 10 a.m. today at Holy Rosary Catholic Church, 724 East Booneslick Road in Warrenton. Burial will follow at 2 p.m. at St. Marcus Cemetery, 7901 Gravois Road.

Survivors, in addition to his wife, include a son, Jeffrey B. Abernathy of St. Louis; a daughter, Rebecca Abernathy of St. Louis; a sister, Norma Smith of Ellisville; and a granddaughter.

By Michael D. Sorkin, Post Dispatch reporter

Son of Glover Eugene and Marcella A. Stone Abernathy

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement