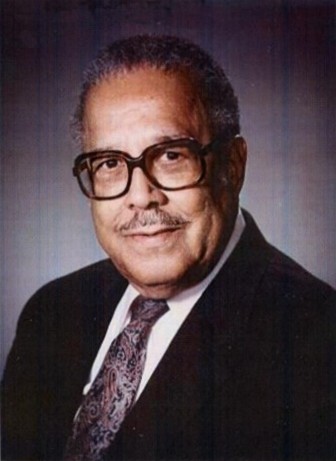

Black was pastor emeritus of Mount Zion First Baptist Church, the largest African-American church in the city.

Known as the "East Side's senior statesman," the respected pastor emerged as one of the African American community's leading activists.

"He set so many standards for so many people," said his grandson, Taj Matthews.

"He was the best father, grandfather, pastor and communty organizer. I just hope this community will always appreciate and continue on the work of both my grandparents," Matthews said.

Black passed away about 10 p.m. after a lengthy illness, Matthews said.

"He was always a man who never showed his anger or his temper," remembered Bill Sinkin, longtime San Antonio businessman and civic leader who worked with Black on various projects over the years. "He showed his strength."

Though he served on the San Antonio City Council from 1973 to 1977 and was its first black mayor pro-tem, he never abandoned the pulpit for politics.

If anything, like in most black churches, Black, a compelling speaker and gifted orator, used the pulpit as a means of expressing his community's struggle for justice and equality.

It was a duty Black never shirked. As a young man, he contributed what money he could spare, mostly nickels and dimes, to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for its effort to obtain equal pay for black teachers.

"My ministry has been one that has not been confined to the walls of institutions," he said a few months before he stepped down from Mount Zion in May 1998. "Being in the ministry is not about making people comfortable, it's about dealing with the uncomfortable."

Ministers, Black noted, were the only ones in the African American community who were not dependent on the white economy.

"The task a minister has is to make life better for people whether they are black, white or Hispanic," he said. "When we talk about saving people, we're talking about individuals who should be able to have justice and the right to express their talents.

"Most of my efforts were designed to address the issues of need that concerned the individual."

That meant that Mount Zion was at the forefront of the fight for equal pay for black teachers, of blacks being treated at tax-supported hospitals, of providing housing for senior citizens, and of building a day care center in 1957 for children whose mothers worked at Kelly and Lackland AFBs.

The church also opened a credit union so that its members would not have to pay exorbitant interest to unscrupulous loan sharks. The credit union expanded its membership and on Jan. 9 changed its name to People's Choice of San Antonio Federal Credit Union.

Along with the late Rabbi David Jacobson, Catholic Archbishop Robert Lucey and Episcopal Bishop Everett Jones, Black fought against segregation.

Black and the Rev. S.H. James Jr., pastor of Second Baptist Church and the man who would become the city's first African American elected to the City Council, helped integrate many of San Antonio's best-known places like the lunch counter at Joske's department store, parks and swimming pools, by setting up picket lines.

"It was one of the most exciting periods a minister can go through," Black recalled in a 2001 interview with San Antonio Express-News columnist Cary Clack. "The civil rights movement, which demanded courage to confront the hostile community but also (the insight) to understand the nature of that hostility; the redefining of blackness to ‘black is beautiful;' the new era of integration, and the transition from protest to politics."

Always outspoken, he was castigated by the establishment for his human rights campaign.

"The newspapers called me militant," Black told Clack. "You're talking about constitutional rights. I was no more militant than the people who wrote the Constitution.''

Black recalled a time when San Antonio was no different than any other city in the United States.

"You had separate facilities for blacks and whites," he said. "If you were black, you had to enter the Majestic Theater from a back entrance and you had to sit in the balcony. You rode in the back of the bus, and the schools were segregated."

Growing up in San Antonio "offered awfully limited experience interracially," Black said, recalling that in his youth, he never saw black bank tellers, store clerks, bus drivers or firefighters.

"There were always stories that were part of family conversations about hostility and about the unpleasant experiences of blacks – not only in San Antonio but in other areas," he said. "So you built up a kind of expectation that if the person was white, you would not expect fairness out of him. You would not expect him to treat you as he would treat others. And I think that was the product, also, of limited contact."

Black was born in San Antonio on Nov. 28, 1916, the son of a Pullman porter and a housewife. After he graduated from then-Douglass High School in 1933, he enrolled at St. Philip's College. He earned a bachelor's degree in 1937 from Morehouse College, an elite black college for men in Atlanta.

He earned a master's degree in divinity from the Andover Newton Theological Seminary, near Boston, in 1943 and returned to San Antonio.

He began his service as pastor at Mount Zion in 1949 and began public ministries that included a day care center, senior services, an emergency food bank and a medical service program, in addition to the credit union. He saw his move into politics as part of his ministry.

In 1945, he founded the San Antonio Mother's Service Organization, the first black group of Christian women to receive a Texas state charter for a local club.

He and several San Antonio Democrats, including Bill Sinkin and former Bexar County Commissioner Albert Peña, stalked out of the 1952 Texas Democratic Convention in protest of the conservative "Dixiecrats" who controlled the party.

Years after the walkout, he campaigned with Lyndon B. Johnson on the East Side.

"I was around when the claim to be treated right and equal was regarded as militant and radical," Black told his congregation in 1998. "I was around when we wanted to be treated as full citizens of this country and have every right that comes with it."

Black ran for a seat on the City Council in 1963 and 1965 but lost. The Good Government League, which controlled city politics at the time, picked him to be its candidate in 1973 and he won an at-large seat on the Council. He served until 1978.

In those days, the mayor was elected by the council. Black backed Charles Becker, son of the Handy Andy grocery chain founder and an independent, for mayor.

After Becker was selected mayor on a 5-4 vote, he appointed Black in 1974 as San Antonio's first African American mayor pro-tem, a potent symbolic position.

As payback, the GGL did not support Black in 1975. He ran as an independent and was re-elected to a second term by a large vote.

"There's something about being a politician that can deteriorate the character of a man if he's not careful, because he's always looking for the compromise position," Black told journalist Sterlin Holmesly for an oral history for the Institute of Texan Cultures.

The same year he was selected mayor pro tem, Mount Zion First Baptist Church was burned to the ground, but no suspects were arrested or charged with the crime. The church was rebuilt in 1975.

Over the years, Black became an associate of Martin Luther King, A. Phillip Randolph, Thurgood Marshall and Adam Clayton Powell Jr.

He gained national attention in his fight for racial equality and marches he led for civil rights. Black attended the White House Conference on Civil Rights in 1966 with President Lyndon B. Johnson and the White House Conference on Aging in 1995 with President Bill Clinton.

After he retired in 1998, Black continued to preach, to write and to speak out on social issues such as education for blacks, racism and economic development in inner city neighborhoods.

"I want to create a community concern for education," he told Clack. "I'm troubled that so many of the low-performing schools are in minority communities. This suggests to the majority community that we're stupid. That's not true. I'm concerned about the young men in prison and the need for education for those in prison."

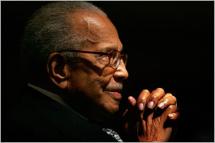

Though in his later years his gait was a little slower, he walked with the aid of a cane, and complained "getting old is not golden," he was still engaged to the present.

Unlike many of his peers, he did not reject computers.

"Even in old age you have to be alert enough to embrace information," he said.

"The one thing I asked of God is that I would not be a non-factor," Black said when the city designated St. Paul Square's South Plaza, the heart of the historic East Side development project, as Claude W. Black Jr. Plaza. "It is very easy for those who love you to make you a non-factor; they don't want you to ever get angry, or to make enemies.

"Those things with meaning are controversial. If you are going to have meaning in your life, you are going to have to enter into things that are controversial."

He lived out that philosophy. Whether railing against segregation or the lack of renovations on the Carver Cultural Center, Black was not shy about speaking about what was on his mind.

"If I had my way, I'd almost insist that every minister serve in public office so that when he came up to the pulpit, he wouldn't be living in a world that he created for himself," Black said.

The voice in which he spoke showed strength, but rarely anger.

"His was the voice of humanity," recalled Mayor Phil Hardberger. "With his wit and wisdom, he reached out to the better angels of our nature."

In his honor, the East Side Multi-Service Center at 2805 E. Commerce St. was re-named the Claude Black Community Center in 1993.

He was appointed a delegate to the 1995 White House Conference on Aging by President Clinton. During the Johnson administration, he was a delegate to the White House Conference on Civil Rights.

Black also served as a commissioner of the San Antonio Development Agency.

In early 2002 he received the Baha'I Unity of Humanity Award from San Antonio members of the faith. He also was named recipient of the 2000 People of Vision Award.

In 2005, he was asked to serve as interim pastor of the church again. Earlier that year, his wife, ZerNona, died. They adopted a daughter, Joyce, who is now deceased.

Black was pastor emeritus of Mount Zion First Baptist Church, the largest African-American church in the city.

Known as the "East Side's senior statesman," the respected pastor emerged as one of the African American community's leading activists.

"He set so many standards for so many people," said his grandson, Taj Matthews.

"He was the best father, grandfather, pastor and communty organizer. I just hope this community will always appreciate and continue on the work of both my grandparents," Matthews said.

Black passed away about 10 p.m. after a lengthy illness, Matthews said.

"He was always a man who never showed his anger or his temper," remembered Bill Sinkin, longtime San Antonio businessman and civic leader who worked with Black on various projects over the years. "He showed his strength."

Though he served on the San Antonio City Council from 1973 to 1977 and was its first black mayor pro-tem, he never abandoned the pulpit for politics.

If anything, like in most black churches, Black, a compelling speaker and gifted orator, used the pulpit as a means of expressing his community's struggle for justice and equality.

It was a duty Black never shirked. As a young man, he contributed what money he could spare, mostly nickels and dimes, to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for its effort to obtain equal pay for black teachers.

"My ministry has been one that has not been confined to the walls of institutions," he said a few months before he stepped down from Mount Zion in May 1998. "Being in the ministry is not about making people comfortable, it's about dealing with the uncomfortable."

Ministers, Black noted, were the only ones in the African American community who were not dependent on the white economy.

"The task a minister has is to make life better for people whether they are black, white or Hispanic," he said. "When we talk about saving people, we're talking about individuals who should be able to have justice and the right to express their talents.

"Most of my efforts were designed to address the issues of need that concerned the individual."

That meant that Mount Zion was at the forefront of the fight for equal pay for black teachers, of blacks being treated at tax-supported hospitals, of providing housing for senior citizens, and of building a day care center in 1957 for children whose mothers worked at Kelly and Lackland AFBs.

The church also opened a credit union so that its members would not have to pay exorbitant interest to unscrupulous loan sharks. The credit union expanded its membership and on Jan. 9 changed its name to People's Choice of San Antonio Federal Credit Union.

Along with the late Rabbi David Jacobson, Catholic Archbishop Robert Lucey and Episcopal Bishop Everett Jones, Black fought against segregation.

Black and the Rev. S.H. James Jr., pastor of Second Baptist Church and the man who would become the city's first African American elected to the City Council, helped integrate many of San Antonio's best-known places like the lunch counter at Joske's department store, parks and swimming pools, by setting up picket lines.

"It was one of the most exciting periods a minister can go through," Black recalled in a 2001 interview with San Antonio Express-News columnist Cary Clack. "The civil rights movement, which demanded courage to confront the hostile community but also (the insight) to understand the nature of that hostility; the redefining of blackness to ‘black is beautiful;' the new era of integration, and the transition from protest to politics."

Always outspoken, he was castigated by the establishment for his human rights campaign.

"The newspapers called me militant," Black told Clack. "You're talking about constitutional rights. I was no more militant than the people who wrote the Constitution.''

Black recalled a time when San Antonio was no different than any other city in the United States.

"You had separate facilities for blacks and whites," he said. "If you were black, you had to enter the Majestic Theater from a back entrance and you had to sit in the balcony. You rode in the back of the bus, and the schools were segregated."

Growing up in San Antonio "offered awfully limited experience interracially," Black said, recalling that in his youth, he never saw black bank tellers, store clerks, bus drivers or firefighters.

"There were always stories that were part of family conversations about hostility and about the unpleasant experiences of blacks – not only in San Antonio but in other areas," he said. "So you built up a kind of expectation that if the person was white, you would not expect fairness out of him. You would not expect him to treat you as he would treat others. And I think that was the product, also, of limited contact."

Black was born in San Antonio on Nov. 28, 1916, the son of a Pullman porter and a housewife. After he graduated from then-Douglass High School in 1933, he enrolled at St. Philip's College. He earned a bachelor's degree in 1937 from Morehouse College, an elite black college for men in Atlanta.

He earned a master's degree in divinity from the Andover Newton Theological Seminary, near Boston, in 1943 and returned to San Antonio.

He began his service as pastor at Mount Zion in 1949 and began public ministries that included a day care center, senior services, an emergency food bank and a medical service program, in addition to the credit union. He saw his move into politics as part of his ministry.

In 1945, he founded the San Antonio Mother's Service Organization, the first black group of Christian women to receive a Texas state charter for a local club.

He and several San Antonio Democrats, including Bill Sinkin and former Bexar County Commissioner Albert Peña, stalked out of the 1952 Texas Democratic Convention in protest of the conservative "Dixiecrats" who controlled the party.

Years after the walkout, he campaigned with Lyndon B. Johnson on the East Side.

"I was around when the claim to be treated right and equal was regarded as militant and radical," Black told his congregation in 1998. "I was around when we wanted to be treated as full citizens of this country and have every right that comes with it."

Black ran for a seat on the City Council in 1963 and 1965 but lost. The Good Government League, which controlled city politics at the time, picked him to be its candidate in 1973 and he won an at-large seat on the Council. He served until 1978.

In those days, the mayor was elected by the council. Black backed Charles Becker, son of the Handy Andy grocery chain founder and an independent, for mayor.

After Becker was selected mayor on a 5-4 vote, he appointed Black in 1974 as San Antonio's first African American mayor pro-tem, a potent symbolic position.

As payback, the GGL did not support Black in 1975. He ran as an independent and was re-elected to a second term by a large vote.

"There's something about being a politician that can deteriorate the character of a man if he's not careful, because he's always looking for the compromise position," Black told journalist Sterlin Holmesly for an oral history for the Institute of Texan Cultures.

The same year he was selected mayor pro tem, Mount Zion First Baptist Church was burned to the ground, but no suspects were arrested or charged with the crime. The church was rebuilt in 1975.

Over the years, Black became an associate of Martin Luther King, A. Phillip Randolph, Thurgood Marshall and Adam Clayton Powell Jr.

He gained national attention in his fight for racial equality and marches he led for civil rights. Black attended the White House Conference on Civil Rights in 1966 with President Lyndon B. Johnson and the White House Conference on Aging in 1995 with President Bill Clinton.

After he retired in 1998, Black continued to preach, to write and to speak out on social issues such as education for blacks, racism and economic development in inner city neighborhoods.

"I want to create a community concern for education," he told Clack. "I'm troubled that so many of the low-performing schools are in minority communities. This suggests to the majority community that we're stupid. That's not true. I'm concerned about the young men in prison and the need for education for those in prison."

Though in his later years his gait was a little slower, he walked with the aid of a cane, and complained "getting old is not golden," he was still engaged to the present.

Unlike many of his peers, he did not reject computers.

"Even in old age you have to be alert enough to embrace information," he said.

"The one thing I asked of God is that I would not be a non-factor," Black said when the city designated St. Paul Square's South Plaza, the heart of the historic East Side development project, as Claude W. Black Jr. Plaza. "It is very easy for those who love you to make you a non-factor; they don't want you to ever get angry, or to make enemies.

"Those things with meaning are controversial. If you are going to have meaning in your life, you are going to have to enter into things that are controversial."

He lived out that philosophy. Whether railing against segregation or the lack of renovations on the Carver Cultural Center, Black was not shy about speaking about what was on his mind.

"If I had my way, I'd almost insist that every minister serve in public office so that when he came up to the pulpit, he wouldn't be living in a world that he created for himself," Black said.

The voice in which he spoke showed strength, but rarely anger.

"His was the voice of humanity," recalled Mayor Phil Hardberger. "With his wit and wisdom, he reached out to the better angels of our nature."

In his honor, the East Side Multi-Service Center at 2805 E. Commerce St. was re-named the Claude Black Community Center in 1993.

He was appointed a delegate to the 1995 White House Conference on Aging by President Clinton. During the Johnson administration, he was a delegate to the White House Conference on Civil Rights.

Black also served as a commissioner of the San Antonio Development Agency.

In early 2002 he received the Baha'I Unity of Humanity Award from San Antonio members of the faith. He also was named recipient of the 2000 People of Vision Award.

In 2005, he was asked to serve as interim pastor of the church again. Earlier that year, his wife, ZerNona, died. They adopted a daughter, Joyce, who is now deceased.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement