The brief and simple service at the First Unitarian Church here reflected the upbeat and unsentimental way in which Mrs. Adkins had lived and chosen to die.

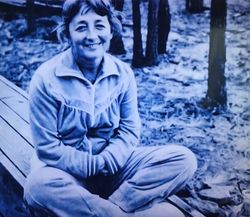

Mrs. Adkins, a 54-year-old musician and teacher who was suffering from Alzheimer's disease, became an immediate national symbol after taking her life last Monday in a Michigan campground in the back of a 22-year-old Volkswagen van with a device developed in Michigan by Dr. Jack Kevorkian.

On Friday a judge in Pontiac, Mich., ordered the doctor to stop using the device while prosecutors decided whether to charge him in connection with Mrs. Adkins' death. The device consists of an intravenous tube through which a person can administer lethal fluid by pressing a button.

Speaking today of the worldwide interest in Mrs. Adkins's decision, the Rev. Alan G. Deale said: ''I do not think Janet intended to become a crusader or a pioneer in the battle for death with dignity. That is, in effect, what has happened.''

Mr. Deale said he had supported Mrs. Adkins's right to decide when she would end her life, and added that once the choice had been made, ''she entered history in a way that I doubt even she, wise woman that she was, would have predicted.'' He added, ''Janet Adkins became a pioneer in the discussion of the matter of death with dignity.''

Mrs. Adkins also was remembered today as a person who took control of her death precisely because she loved life.

''She was a very upbeat person,'' said her husband, Ronald, before the service. Mrs. Adkins, the mother of three and grandmother of three, taught piano at home and English at the local community college.

The service included readings and music selected by Mrs. Adkins. Among them were a string quartet by Borodin, a folk song, ''When I Need You,'' and Beethoven's ''Ode to Joy.''

Mr. Adkins said his wife's role in planning the service was part of the ''closing process'' through which she insisted on keeping control of the ending of her life, even as her sickness began to rob her of control.

According to her wishes, Mr. Adkins said, he arranged for a funeral home to cremate her body, once an autopsy is completed, and to have her ashes scattered over the ocean. He said these actions would be taken without family participation.

But despite her careful planning, Mr. Adkins said, his wife's death had taken an unexpected turn when it drew worldwide publicity.

''This was something we had not foreseen, not to this extent,'' he said. ''Janet and I were told by the doctor that this would probably be a newsworthy item and that there would be some controversy over it, but I never envisioned anything to this extent.''

Mr. Adkins said his wife had viewed her illness as ''a bad joke'' but that the amount of publicity might be a sign that it had had a purpose, to bring questions of death and self-determination into the open.

Alzheimer's disease, which causes progressive memory loss and often, in its final stages, total debilitation, is considered to be incurable. It is the nation's fourth-leading cause of death.

About a year ago, after Mrs. Adkins's disease was diagnosed as Alzheimer's, her family said, she began making plans to take her own life before the symptoms became advanced.

Mrs. Adkins had begun to suffer small gaps in memory, but had remained alert and vigorous enough to beat her son in tennis a week before her death.

Today's service was led by Mr. Deale according to instructions Mrs. Adkins gave him at a meeting on May 31.

Of that meeting, Mr. Deale said: ''When she was sitting here that day, I said to her, 'You look fine to me.' But she said, 'I can't remember my music. I can't remember the scores. And I begin to see the beginning of the deterioration and I don't want to go through with that deterioration.' ''

Mr. Deale said it was his sense, as he met that final time with Mrs. Adkins, that the decisions of a dying person must be honored. The strength and calm in Mrs. Adkins' bearing only reinforced that sense, he said.

''As she and her husband got up to leave, I said, 'If this is the last time I am going to see you, we should have a hug.' And she said, 'We sure should,' and she gave me a great big hug and went out the door.''

Credit: New York Times, published June 11, 1990

The brief and simple service at the First Unitarian Church here reflected the upbeat and unsentimental way in which Mrs. Adkins had lived and chosen to die.

Mrs. Adkins, a 54-year-old musician and teacher who was suffering from Alzheimer's disease, became an immediate national symbol after taking her life last Monday in a Michigan campground in the back of a 22-year-old Volkswagen van with a device developed in Michigan by Dr. Jack Kevorkian.

On Friday a judge in Pontiac, Mich., ordered the doctor to stop using the device while prosecutors decided whether to charge him in connection with Mrs. Adkins' death. The device consists of an intravenous tube through which a person can administer lethal fluid by pressing a button.

Speaking today of the worldwide interest in Mrs. Adkins's decision, the Rev. Alan G. Deale said: ''I do not think Janet intended to become a crusader or a pioneer in the battle for death with dignity. That is, in effect, what has happened.''

Mr. Deale said he had supported Mrs. Adkins's right to decide when she would end her life, and added that once the choice had been made, ''she entered history in a way that I doubt even she, wise woman that she was, would have predicted.'' He added, ''Janet Adkins became a pioneer in the discussion of the matter of death with dignity.''

Mrs. Adkins also was remembered today as a person who took control of her death precisely because she loved life.

''She was a very upbeat person,'' said her husband, Ronald, before the service. Mrs. Adkins, the mother of three and grandmother of three, taught piano at home and English at the local community college.

The service included readings and music selected by Mrs. Adkins. Among them were a string quartet by Borodin, a folk song, ''When I Need You,'' and Beethoven's ''Ode to Joy.''

Mr. Adkins said his wife's role in planning the service was part of the ''closing process'' through which she insisted on keeping control of the ending of her life, even as her sickness began to rob her of control.

According to her wishes, Mr. Adkins said, he arranged for a funeral home to cremate her body, once an autopsy is completed, and to have her ashes scattered over the ocean. He said these actions would be taken without family participation.

But despite her careful planning, Mr. Adkins said, his wife's death had taken an unexpected turn when it drew worldwide publicity.

''This was something we had not foreseen, not to this extent,'' he said. ''Janet and I were told by the doctor that this would probably be a newsworthy item and that there would be some controversy over it, but I never envisioned anything to this extent.''

Mr. Adkins said his wife had viewed her illness as ''a bad joke'' but that the amount of publicity might be a sign that it had had a purpose, to bring questions of death and self-determination into the open.

Alzheimer's disease, which causes progressive memory loss and often, in its final stages, total debilitation, is considered to be incurable. It is the nation's fourth-leading cause of death.

About a year ago, after Mrs. Adkins's disease was diagnosed as Alzheimer's, her family said, she began making plans to take her own life before the symptoms became advanced.

Mrs. Adkins had begun to suffer small gaps in memory, but had remained alert and vigorous enough to beat her son in tennis a week before her death.

Today's service was led by Mr. Deale according to instructions Mrs. Adkins gave him at a meeting on May 31.

Of that meeting, Mr. Deale said: ''When she was sitting here that day, I said to her, 'You look fine to me.' But she said, 'I can't remember my music. I can't remember the scores. And I begin to see the beginning of the deterioration and I don't want to go through with that deterioration.' ''

Mr. Deale said it was his sense, as he met that final time with Mrs. Adkins, that the decisions of a dying person must be honored. The strength and calm in Mrs. Adkins' bearing only reinforced that sense, he said.

''As she and her husband got up to leave, I said, 'If this is the last time I am going to see you, we should have a hug.' And she said, 'We sure should,' and she gave me a great big hug and went out the door.''

Credit: New York Times, published June 11, 1990

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement