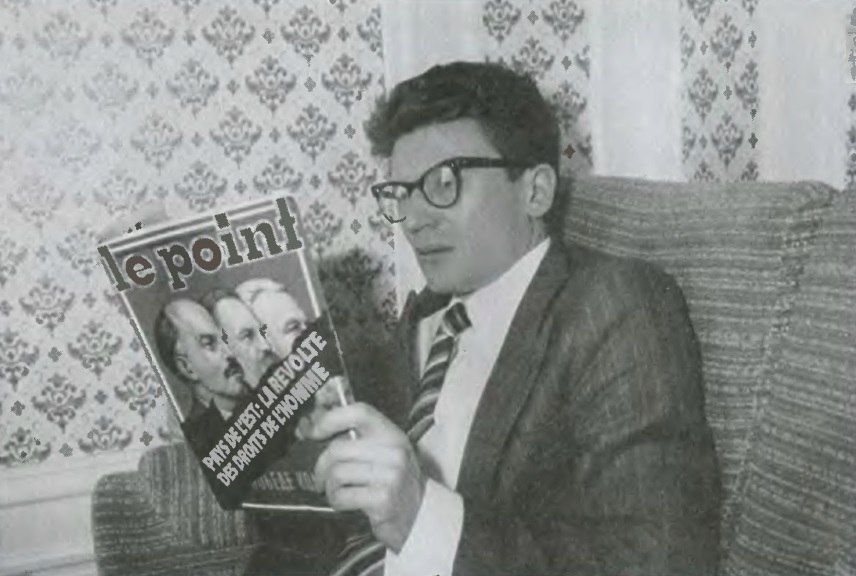

was a Russian writer and dissident.

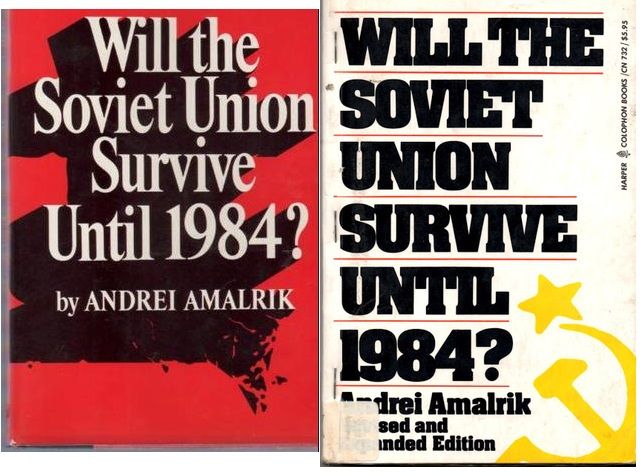

Amalrik was best known in the Western world for his 1970 essay, Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?

~~~

obituary:

Andrei Amalrik, one of the first human rights activists in the postwar. Soviet Union and a man who suffered years of imprisonment and exile before emigrating to the West, died yesterday in an automobile accident near Madrid. He was 42.

A historian and a polemicist -- author of the celebrated essay "Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?" -- Mr. Amalrik was a central figure in the disparate group of Soviet citizens that came to be known as the Democratic Movement in the late 1960s.

He was the first dissident actively to seek out American correspondents in Moscow in the mid-1960s, foreshadowing a relationship that subsequently evolved between Soviet political dissidents, and Western journalists that led to wide distribution of dissident views via Western broadcasts to Russia.

He was pressured to leave the Soviet Union in 1976 and has since lectured at universities in the Netherlands and the United States, including Harvard and George Washington University.

Mr. Amalrik was on his way to the Spanish capital to attend a meeting of Soviet human rights activists staged to coincide with the current follow-up conference on European security and cooperation when his car went out of control and collided with a truck.

Hospital officials said he was apparently killed by a piece of metal from the truck that pierced his neck. His wife, Gyuzel, a painter, and two fellow dissidents traveling with them all escaped injuries.

Mr. Amalrik's latest book, "Notes of a Revolutionary," has just been translated and is scheduled to be published by Alfred A. Knopf next fall. His editor, Ashbel Green, described the work as a memoir dealing largely with Mr. Amalrik's experiences in the decade just before he left the Soviet Union.

A frail but feisty man, Mr. Amalrik became a symbol of opposition in the Soviet Union long before such figures as Andrei Sakharov and Alexander Solzhenitsyn. He was expelled from Moscow University in 1963 because his dissertation advanced unorthodox views about early Russian history. Mr. Amalrik maintained that the Vikings played a decisive influence in civilizing Slavic tribes in Russia -- a view that went against the grain of the official intepretation of Russian history.

He subsequently decided to become a writer and wrote several plays. He also came to know many avant garde Moscow artists and in 1965 was tried on charges of being a "social parasite" because he had no permanent job. Underlying the charge was apparent official concern that he was facilitating contacts between artists and foreign journalists and diplomats.

After two months in prison, he spent just a year in Siberian exile. Afterwards he wrote his "Involuntary Journey to Siberia" in which he described his experiences.

He became a celebrity in the West following his apocalyptic essay "Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?" The Book-of-the-Month Club thought the 112-page book so important that it sent a free copy to all its members and to every college and university library in North America.

In the book, he forecast a military showdown between the Soviet Union and China that would help trigger an internal collapse in the Soviet Union between 1980 and 1985. Years later, he conceded that his doomsday scenario may be inaccurate and that he had underestimated the Kremlin's flexibility and overestimated China's ability to build a modern army.

In May 1970, he was arrested and charged with slandering the Soviet state. He spent three years in prison and two years in Siberia before returing to Moscow in 1975.

Refusing to take part in court proceedings, Mr. Amalrik pleaded innocent in a written statement that said: "I think the truth or falseness of publicly expressed views can be ascertained by free and open discussion, not by a judicial investigation. No criminal court has the moral right to try anyone for the views he has expressed.

"To sentence ideas to criminal punishment, whether they be true or false, seems to me to be a crime in itself."

Mr. Amalrik was a unique figure in Moscow's dissident community. He was a loner with a strong philosophical bent. The struggle for human rights in Russia, he once said, is difficult because of the absence of a tradition of freedom. This, in turn, frequently pitted human rights activists not only against the government but also against the people for whom these rights are sought.

In his solitary protests he was joined only by his wife. Otherwise, he was a self-contained man, or as he described himself once, "the first complete dissident, a person really outside the system." For this reason he felt that he irritated the authorities, and they continued to harass him until he decided to leave the country.

Mr. Amalrik was driving overnight from Marseilles to Madrid when the accident occurred near the provincial city of Guadalajara early yesterday. Apart from his wife, the passengers in the car were identified as fellow dissidents Viktor Feinburg and Vladimir Borisov.

Robert Bernstein, chairman of the U.S. Helsinki Watch Committee, said in a statement that "it is both tragic and ironic that Andrei died at this time, on his way to Madrid, where he planned to speak out once again about human rights abuses in his country. He will be remembered for his unbreakable spirit, as a man who always spoke his mind."

It was not immediately known where Mr. Amalrik will be buried.

was a Russian writer and dissident.

Amalrik was best known in the Western world for his 1970 essay, Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?

~~~

obituary:

Andrei Amalrik, one of the first human rights activists in the postwar. Soviet Union and a man who suffered years of imprisonment and exile before emigrating to the West, died yesterday in an automobile accident near Madrid. He was 42.

A historian and a polemicist -- author of the celebrated essay "Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?" -- Mr. Amalrik was a central figure in the disparate group of Soviet citizens that came to be known as the Democratic Movement in the late 1960s.

He was the first dissident actively to seek out American correspondents in Moscow in the mid-1960s, foreshadowing a relationship that subsequently evolved between Soviet political dissidents, and Western journalists that led to wide distribution of dissident views via Western broadcasts to Russia.

He was pressured to leave the Soviet Union in 1976 and has since lectured at universities in the Netherlands and the United States, including Harvard and George Washington University.

Mr. Amalrik was on his way to the Spanish capital to attend a meeting of Soviet human rights activists staged to coincide with the current follow-up conference on European security and cooperation when his car went out of control and collided with a truck.

Hospital officials said he was apparently killed by a piece of metal from the truck that pierced his neck. His wife, Gyuzel, a painter, and two fellow dissidents traveling with them all escaped injuries.

Mr. Amalrik's latest book, "Notes of a Revolutionary," has just been translated and is scheduled to be published by Alfred A. Knopf next fall. His editor, Ashbel Green, described the work as a memoir dealing largely with Mr. Amalrik's experiences in the decade just before he left the Soviet Union.

A frail but feisty man, Mr. Amalrik became a symbol of opposition in the Soviet Union long before such figures as Andrei Sakharov and Alexander Solzhenitsyn. He was expelled from Moscow University in 1963 because his dissertation advanced unorthodox views about early Russian history. Mr. Amalrik maintained that the Vikings played a decisive influence in civilizing Slavic tribes in Russia -- a view that went against the grain of the official intepretation of Russian history.

He subsequently decided to become a writer and wrote several plays. He also came to know many avant garde Moscow artists and in 1965 was tried on charges of being a "social parasite" because he had no permanent job. Underlying the charge was apparent official concern that he was facilitating contacts between artists and foreign journalists and diplomats.

After two months in prison, he spent just a year in Siberian exile. Afterwards he wrote his "Involuntary Journey to Siberia" in which he described his experiences.

He became a celebrity in the West following his apocalyptic essay "Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?" The Book-of-the-Month Club thought the 112-page book so important that it sent a free copy to all its members and to every college and university library in North America.

In the book, he forecast a military showdown between the Soviet Union and China that would help trigger an internal collapse in the Soviet Union between 1980 and 1985. Years later, he conceded that his doomsday scenario may be inaccurate and that he had underestimated the Kremlin's flexibility and overestimated China's ability to build a modern army.

In May 1970, he was arrested and charged with slandering the Soviet state. He spent three years in prison and two years in Siberia before returing to Moscow in 1975.

Refusing to take part in court proceedings, Mr. Amalrik pleaded innocent in a written statement that said: "I think the truth or falseness of publicly expressed views can be ascertained by free and open discussion, not by a judicial investigation. No criminal court has the moral right to try anyone for the views he has expressed.

"To sentence ideas to criminal punishment, whether they be true or false, seems to me to be a crime in itself."

Mr. Amalrik was a unique figure in Moscow's dissident community. He was a loner with a strong philosophical bent. The struggle for human rights in Russia, he once said, is difficult because of the absence of a tradition of freedom. This, in turn, frequently pitted human rights activists not only against the government but also against the people for whom these rights are sought.

In his solitary protests he was joined only by his wife. Otherwise, he was a self-contained man, or as he described himself once, "the first complete dissident, a person really outside the system." For this reason he felt that he irritated the authorities, and they continued to harass him until he decided to leave the country.

Mr. Amalrik was driving overnight from Marseilles to Madrid when the accident occurred near the provincial city of Guadalajara early yesterday. Apart from his wife, the passengers in the car were identified as fellow dissidents Viktor Feinburg and Vladimir Borisov.

Robert Bernstein, chairman of the U.S. Helsinki Watch Committee, said in a statement that "it is both tragic and ironic that Andrei died at this time, on his way to Madrid, where he planned to speak out once again about human rights abuses in his country. He will be remembered for his unbreakable spirit, as a man who always spoke his mind."

It was not immediately known where Mr. Amalrik will be buried.

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement