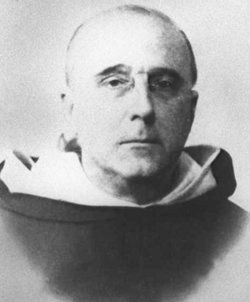

Gontran-Marie Garrigou-Lagrange was born in Auch, Midi-Pyrénées, France, on February 21, 1877, into a solid Catholic family living in the south-west of France. In 1896, he began studies in medicine at the University of Bordeaux, but whilst there he read a book by the Catholic philosopher Ernest Hello which changed the direction of his life.

Medical studies abandoned, Gontran-Marie entered the French Dominicans at the age of twenty, and received the religious name of Reginald, after Blessed Reginald of Orleans, a contemporary of St Dominic, to whom Our Lady appeared in a vision, curing him of a mortal sickness and gaving him a white scapular that thereupon became part of the Dominican habit. Friar Reginald had the good fortune to receive his initial training from Dominicans committed to implementing Pope Leo XIII's encyclical letter "Aeterni Patris", the document that insisted upon the unique place of St. Thomas Aquinas in philosophy and theology. It was by studying the Angelic Doctor that the young Garrigou-Lagrange nourished the conviction that had brought him to the cloister: the unchangeableness of revealed truth.

His superiors clearly perceived his abilities, for after ordination in 1902, Reginald was enrolled for further philosophical studies at the Sorbonne in Paris. It was a mark of the trust that his superiors placed in him that he was sent to so aggressively secular an environment while still a young priest. Among his lecturers were Henri Bergson, Emile Durkheim, and the not yet excommunicated Alfred Loïsy, the 'Father of Modernism'. His fellow students included the future philosopher Jacques Maritain, not yet a Catholic and indeed driven almost to despair by the prevailing nihilism of the great French university. Father Garrigou's relations with Maritain were later to be both fruitful and troubled.

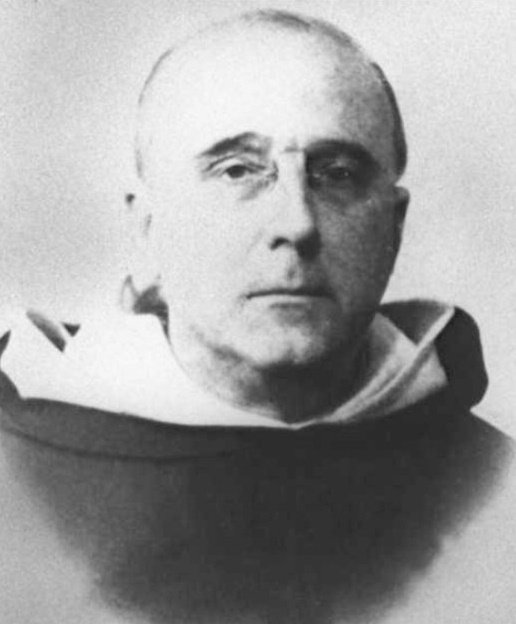

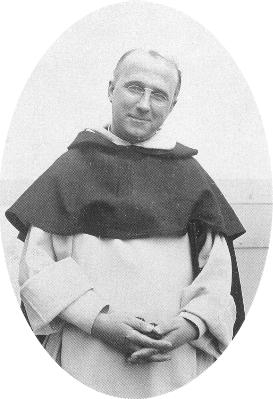

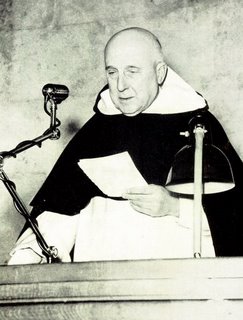

In 1906, Fr. Reginald was assigned to teach philosophy at Le Saulchoir, the house of studies of the French Dominicans. His pedagogic skill was such that in 1909, at the age of thirty-two, he was sent to teach at the Dominican University in Rome, the Angelicum. Here he remained for the next fifty years, teaching three courses: Aristotle, apologetics and spiritual theology. He had the gift of making the most difficult subjects clear, and of showing how sound philosophy and revealed truth fit together in a wonderful harmony. Father Garrigou clearly loved his work: one of his students remembered him exclaiming, "I could teach Aristotle for three hundred years and never grow tired!" He also possessed what is perhaps the rarer gift of communicating his own zest for a subject to his listeners, for his lectures, abstract though they were, were not dull affairs. One student paints this portrait of Fr. Garrigou lecturing: "His small eyes were filled with mischief and laughter, his body was constantly moving, his face was able to assume attitudes of horror, anger, irony, indignation and wonder."

In his defence of Catholic doctrine according to the principles of St. Thomas, Fr. Garrigou was greatly aided by Jacques Maritain. Maritain, originally from a markedly anti-clerical family, entered the Church in 1906, and was to become the most brilliant Thomist philosopher of the twentieth century, dying in 1973. Between the two wars, Garrigou-Lagrange and Maritain organised the 'Thomist Study Circles'. These were groups of laymen committed to the spiritual life who studied St. Thomas and the Thomist tradition, and who met once a year for a five-day retreat preached by Fr. Garrigou at the Maritains' house in Meudon. The study circles were highly successful, and Meudon became a seed-bed of vocations. The young Yves Congar, who was later to write somewhat bitterly about Garrigou-Lagrange, was present at some of the retreats preached by the Dominican friar at Meudon, and later recalled: "He made a profound impression on me. Some of his sermons filled me with enthusiasm and greatly satisfied me by their clarity, their rigour, their breadth and their spirit of faith."

Throughout this period Garrigou-Lagrange's reputation grew and became international. His lectures at the Angelicum on the spiritual life were particularly in demand. According to one author they became "one of the unofficial tourist sites for theologically-minded visitors to Rome", attracting students from other universities and even experienced priests who wished to learn more about spiritual direction.

It is perhaps in this field of mystical, or spiritual, theology that Garrigou's most original work was done. As early as 1917, a special professorship in ascetical and mystical theology had been created for him at the Angelicum, the first of its kind anywhere in the world. His great achievement was to synthesise the highly abstract writings of St. Thomas Aquinas with the 'experiential' writings of St. John of the Cross, showing how they are in perfect harmony with each other. The one describes the spiritual life from the point of view, so to speak, of God, analysing the manifold graces that He gives to the soul to bring it into union with Himself; the other describes the same process from the point of view of man, showing the 'attitudes' that a faithful soul should adopt at various stages of the spiritual journey. It must have been particularly pleasing for Fr. Garrigou when St. John of the Cross, whose orthodoxy had once been doubted by some writers, was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XI.

The role of university professor naturally brought with it the obligation of supervising doctoral students. It is said that Garrigou considered his best student to have been his fellow French Dominican, Marie-Dominique Chenu. Chenu's later career, however, must have been a disappointment to his mentor, for he went on to distance himself from the kind of Thomism traditionally practised in the Dominican Order in favour of a far more 'historical' approach to the subject. Fr. Garrigou, however, was always less interested in historical questions of who influenced whom than in discovering where truth in itself lay. It also seems unlikely that Garrigou would have been impressed by Chenu's involvement in the worker-priest movement. Another doctoral student of Father Garrigou's, and one destined for an even more prominent role in the Church than Chenu, was a young Polish priest named Karol Wojtyła. Under Garrigou-Lagrange's direction the future Pope wrote a thesis in Spanish on 'The meaning of faith in the writings of St. John of the Cross.'

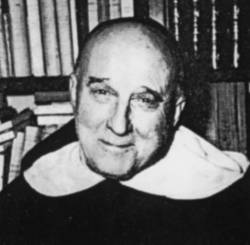

After the Second World War, Fr. Garrigou continued to teach in Rome. Over the years, his lecture notes were turned into an impressive array of books, the more technical ones being published in Latin and the more popular ones in French. In particular he commented on St. Thomas Aquinas's "Summa Theologiæ", taking his place in the line of the great commentators on that work, a line that stretches back to the Middle Ages.

No portrait of Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange would be complete without reference to his religious life. For if he was an internationally renowned professor, he was above all a friar of the Order of Preachers. He was known, in fact, for his fidelity to the regular life. Although dispensations from the choral office were readily available in the Dominican Order for someone with his teaching load, Fr. Reginald was habitually present in Choir. He would have gladly echoed a remark made by St. John Bosco to his religious: "Liturgy is our entertainment." We are told that he was very modest in matters of food and drink and that he felt that it was hardly compatible with religious poverty to smoke. His cell at the Angelicum was the most spartan in the priory, with no ornamentation, and a bed that was, in the words of one contemporary, "a pallet and a mattress so thin that it was virtually just an empty sack." It was not that he had no attraction for the things of the senses - as a young man he had learned to love the music of Beethoven, a love that remained with him through life.

Father Garrigou had worked in various capacities for the Holy Office from the days of Benedict XV onwards, and in the late 1950's Pope John XXIII invited him to join the theological commission that was preparing documents for the Second Vatican Council. But by this time his strength was failing, and he had to decline. He gave his last lecture at the Angelicum shortly before Christmas of 1959. For the next five years Friar Reginald lived in a serene decline of his mental faculties. As his mind and his eyes failed, this great theologian who had once written so subtly of potentiality and act, of sufficient and efficacious grace, of the inner life of God and the glory of Heaven, would remain in his bare cell or in the priory church, praying his Rosary and awaiting his own transitus. He died on February 15, 1964, the feast of one of the greatest of Dominican mystics, Blessed Henry Suso.

Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange wrote 28 books and over 600 articles. His best-known work of mystical theology is the two-volume study, "The Three Ages of the Interior Life". This is in effect a summa of his research in this field. Many people, laymen, religious and priests, have found it very valuable. "De Revelatione", regarding apologetics, is also considered as an austere masterpiece.

Gontran-Marie Garrigou-Lagrange was born in Auch, Midi-Pyrénées, France, on February 21, 1877, into a solid Catholic family living in the south-west of France. In 1896, he began studies in medicine at the University of Bordeaux, but whilst there he read a book by the Catholic philosopher Ernest Hello which changed the direction of his life.

Medical studies abandoned, Gontran-Marie entered the French Dominicans at the age of twenty, and received the religious name of Reginald, after Blessed Reginald of Orleans, a contemporary of St Dominic, to whom Our Lady appeared in a vision, curing him of a mortal sickness and gaving him a white scapular that thereupon became part of the Dominican habit. Friar Reginald had the good fortune to receive his initial training from Dominicans committed to implementing Pope Leo XIII's encyclical letter "Aeterni Patris", the document that insisted upon the unique place of St. Thomas Aquinas in philosophy and theology. It was by studying the Angelic Doctor that the young Garrigou-Lagrange nourished the conviction that had brought him to the cloister: the unchangeableness of revealed truth.

His superiors clearly perceived his abilities, for after ordination in 1902, Reginald was enrolled for further philosophical studies at the Sorbonne in Paris. It was a mark of the trust that his superiors placed in him that he was sent to so aggressively secular an environment while still a young priest. Among his lecturers were Henri Bergson, Emile Durkheim, and the not yet excommunicated Alfred Loïsy, the 'Father of Modernism'. His fellow students included the future philosopher Jacques Maritain, not yet a Catholic and indeed driven almost to despair by the prevailing nihilism of the great French university. Father Garrigou's relations with Maritain were later to be both fruitful and troubled.

In 1906, Fr. Reginald was assigned to teach philosophy at Le Saulchoir, the house of studies of the French Dominicans. His pedagogic skill was such that in 1909, at the age of thirty-two, he was sent to teach at the Dominican University in Rome, the Angelicum. Here he remained for the next fifty years, teaching three courses: Aristotle, apologetics and spiritual theology. He had the gift of making the most difficult subjects clear, and of showing how sound philosophy and revealed truth fit together in a wonderful harmony. Father Garrigou clearly loved his work: one of his students remembered him exclaiming, "I could teach Aristotle for three hundred years and never grow tired!" He also possessed what is perhaps the rarer gift of communicating his own zest for a subject to his listeners, for his lectures, abstract though they were, were not dull affairs. One student paints this portrait of Fr. Garrigou lecturing: "His small eyes were filled with mischief and laughter, his body was constantly moving, his face was able to assume attitudes of horror, anger, irony, indignation and wonder."

In his defence of Catholic doctrine according to the principles of St. Thomas, Fr. Garrigou was greatly aided by Jacques Maritain. Maritain, originally from a markedly anti-clerical family, entered the Church in 1906, and was to become the most brilliant Thomist philosopher of the twentieth century, dying in 1973. Between the two wars, Garrigou-Lagrange and Maritain organised the 'Thomist Study Circles'. These were groups of laymen committed to the spiritual life who studied St. Thomas and the Thomist tradition, and who met once a year for a five-day retreat preached by Fr. Garrigou at the Maritains' house in Meudon. The study circles were highly successful, and Meudon became a seed-bed of vocations. The young Yves Congar, who was later to write somewhat bitterly about Garrigou-Lagrange, was present at some of the retreats preached by the Dominican friar at Meudon, and later recalled: "He made a profound impression on me. Some of his sermons filled me with enthusiasm and greatly satisfied me by their clarity, their rigour, their breadth and their spirit of faith."

Throughout this period Garrigou-Lagrange's reputation grew and became international. His lectures at the Angelicum on the spiritual life were particularly in demand. According to one author they became "one of the unofficial tourist sites for theologically-minded visitors to Rome", attracting students from other universities and even experienced priests who wished to learn more about spiritual direction.

It is perhaps in this field of mystical, or spiritual, theology that Garrigou's most original work was done. As early as 1917, a special professorship in ascetical and mystical theology had been created for him at the Angelicum, the first of its kind anywhere in the world. His great achievement was to synthesise the highly abstract writings of St. Thomas Aquinas with the 'experiential' writings of St. John of the Cross, showing how they are in perfect harmony with each other. The one describes the spiritual life from the point of view, so to speak, of God, analysing the manifold graces that He gives to the soul to bring it into union with Himself; the other describes the same process from the point of view of man, showing the 'attitudes' that a faithful soul should adopt at various stages of the spiritual journey. It must have been particularly pleasing for Fr. Garrigou when St. John of the Cross, whose orthodoxy had once been doubted by some writers, was declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XI.

The role of university professor naturally brought with it the obligation of supervising doctoral students. It is said that Garrigou considered his best student to have been his fellow French Dominican, Marie-Dominique Chenu. Chenu's later career, however, must have been a disappointment to his mentor, for he went on to distance himself from the kind of Thomism traditionally practised in the Dominican Order in favour of a far more 'historical' approach to the subject. Fr. Garrigou, however, was always less interested in historical questions of who influenced whom than in discovering where truth in itself lay. It also seems unlikely that Garrigou would have been impressed by Chenu's involvement in the worker-priest movement. Another doctoral student of Father Garrigou's, and one destined for an even more prominent role in the Church than Chenu, was a young Polish priest named Karol Wojtyła. Under Garrigou-Lagrange's direction the future Pope wrote a thesis in Spanish on 'The meaning of faith in the writings of St. John of the Cross.'

After the Second World War, Fr. Garrigou continued to teach in Rome. Over the years, his lecture notes were turned into an impressive array of books, the more technical ones being published in Latin and the more popular ones in French. In particular he commented on St. Thomas Aquinas's "Summa Theologiæ", taking his place in the line of the great commentators on that work, a line that stretches back to the Middle Ages.

No portrait of Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange would be complete without reference to his religious life. For if he was an internationally renowned professor, he was above all a friar of the Order of Preachers. He was known, in fact, for his fidelity to the regular life. Although dispensations from the choral office were readily available in the Dominican Order for someone with his teaching load, Fr. Reginald was habitually present in Choir. He would have gladly echoed a remark made by St. John Bosco to his religious: "Liturgy is our entertainment." We are told that he was very modest in matters of food and drink and that he felt that it was hardly compatible with religious poverty to smoke. His cell at the Angelicum was the most spartan in the priory, with no ornamentation, and a bed that was, in the words of one contemporary, "a pallet and a mattress so thin that it was virtually just an empty sack." It was not that he had no attraction for the things of the senses - as a young man he had learned to love the music of Beethoven, a love that remained with him through life.

Father Garrigou had worked in various capacities for the Holy Office from the days of Benedict XV onwards, and in the late 1950's Pope John XXIII invited him to join the theological commission that was preparing documents for the Second Vatican Council. But by this time his strength was failing, and he had to decline. He gave his last lecture at the Angelicum shortly before Christmas of 1959. For the next five years Friar Reginald lived in a serene decline of his mental faculties. As his mind and his eyes failed, this great theologian who had once written so subtly of potentiality and act, of sufficient and efficacious grace, of the inner life of God and the glory of Heaven, would remain in his bare cell or in the priory church, praying his Rosary and awaiting his own transitus. He died on February 15, 1964, the feast of one of the greatest of Dominican mystics, Blessed Henry Suso.

Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange wrote 28 books and over 600 articles. His best-known work of mystical theology is the two-volume study, "The Three Ages of the Interior Life". This is in effect a summa of his research in this field. Many people, laymen, religious and priests, have found it very valuable. "De Revelatione", regarding apologetics, is also considered as an austere masterpiece.

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement