He spent his youth working around the British military complexes , doing menial domestic jobs. When an oportunity arose for him to enlist in the Indian Army and sail away to help the British war effort, he lost no time in accepting it. He was of low caste, poorly paid, with no family of his own, so the promise of higher wages, good quality meals and a trip across the world seemed to good to miss. He was excited and looked forward to an adventure serving the King.

On the journey across the oceans, he worked hard keeping the holding pens of the many horses and mules who travelled on board with the army clean. He swept their stalls, fed them and brushed their coats.

As the weeks passed he bagan to become ill. He disliked the cold weather encountered at sea, the rain lashing at the ship, rocking those on board. He suffered with sea sickness and lay down on the straw next to the mules to try and sleep.

On arrival in France on a cold October day in 1914 he faithfully followed the soldiers as they marched to their encampent. He was happy to see rosy-cheeked children run up and grasp his hand. He was happy to be back on dry land.

His job in France was to sweep and clean the military camps. At times he was sent to the trenches to help remove the dead, dying and injurered. He was horrified at the sights and sounds of trench warfare, but dilligently kept up with his work, comforted in the knowledge that he was helping other people while battle raged all around them.

After a few weeks he was ordered to travel on a hospital ship with injured soldiers to England. On arrival at Southampton docks, he was sent through the lush green New Forest, to work as a cleaning attendant at Lady Hardinge Hospital at Brockenhurst, which was catered for injured soldiers of the Indian Army. He was happy to be helping the nursing staff. They barely noticed him, Indian soldiers ignored him. His low caste marked him out as "untouchable", but he was not upset. He knew how the differences between castes worked. He understood his place in society.

After a month of living in England he once more became ill, he constantly felt cold, weak and tired, but he carried on with his work. He knew it was an essential part of the hospital work and was glad to be of help.

One day while sweeping one of the hospital wards, Sukha collapsed and was sent to rest on his bed. His body was overcome with infection. His lungs burned and he could not eat. He was very weak and he missed the warmth of the sun back home

He was nursed in one of the wards where he had swept and cleaned. It felt strange to be a patient, but he was glad of a warm blanket to sleep under.

He died of Pneumonia on 13th January, 1915 at Lady Hardinge Hospital. He had gone from employee to patient within just a few weeks.

Due to his low caste, his fellow Hindu's refused to allow his body to be cremated at their site in Patcham, East Sussex.

An appeal was sent to Maulvi Sadr-ur-Din in Wokingham, Berkshire, but they too refused to deal with his body on the grounds that he was not of Muslim faith.

Due to religious and caste practices, he was denied a traditional burial.

On hearing about Sukha being denied a traditional cremation, Arthur CHAMBERS, the Vicar of St. Nicholas Church, Brockenhurst decided that Sukha had helped with the war effort and had died for England, so he arranged for him to be buried in the peaceful grounds of his parish church at the heart of the New Forest..

He spent his youth working around the British military complexes , doing menial domestic jobs. When an oportunity arose for him to enlist in the Indian Army and sail away to help the British war effort, he lost no time in accepting it. He was of low caste, poorly paid, with no family of his own, so the promise of higher wages, good quality meals and a trip across the world seemed to good to miss. He was excited and looked forward to an adventure serving the King.

On the journey across the oceans, he worked hard keeping the holding pens of the many horses and mules who travelled on board with the army clean. He swept their stalls, fed them and brushed their coats.

As the weeks passed he bagan to become ill. He disliked the cold weather encountered at sea, the rain lashing at the ship, rocking those on board. He suffered with sea sickness and lay down on the straw next to the mules to try and sleep.

On arrival in France on a cold October day in 1914 he faithfully followed the soldiers as they marched to their encampent. He was happy to see rosy-cheeked children run up and grasp his hand. He was happy to be back on dry land.

His job in France was to sweep and clean the military camps. At times he was sent to the trenches to help remove the dead, dying and injurered. He was horrified at the sights and sounds of trench warfare, but dilligently kept up with his work, comforted in the knowledge that he was helping other people while battle raged all around them.

After a few weeks he was ordered to travel on a hospital ship with injured soldiers to England. On arrival at Southampton docks, he was sent through the lush green New Forest, to work as a cleaning attendant at Lady Hardinge Hospital at Brockenhurst, which was catered for injured soldiers of the Indian Army. He was happy to be helping the nursing staff. They barely noticed him, Indian soldiers ignored him. His low caste marked him out as "untouchable", but he was not upset. He knew how the differences between castes worked. He understood his place in society.

After a month of living in England he once more became ill, he constantly felt cold, weak and tired, but he carried on with his work. He knew it was an essential part of the hospital work and was glad to be of help.

One day while sweeping one of the hospital wards, Sukha collapsed and was sent to rest on his bed. His body was overcome with infection. His lungs burned and he could not eat. He was very weak and he missed the warmth of the sun back home

He was nursed in one of the wards where he had swept and cleaned. It felt strange to be a patient, but he was glad of a warm blanket to sleep under.

He died of Pneumonia on 13th January, 1915 at Lady Hardinge Hospital. He had gone from employee to patient within just a few weeks.

Due to his low caste, his fellow Hindu's refused to allow his body to be cremated at their site in Patcham, East Sussex.

An appeal was sent to Maulvi Sadr-ur-Din in Wokingham, Berkshire, but they too refused to deal with his body on the grounds that he was not of Muslim faith.

Due to religious and caste practices, he was denied a traditional burial.

On hearing about Sukha being denied a traditional cremation, Arthur CHAMBERS, the Vicar of St. Nicholas Church, Brockenhurst decided that Sukha had helped with the war effort and had died for England, so he arranged for him to be buried in the peaceful grounds of his parish church at the heart of the New Forest..

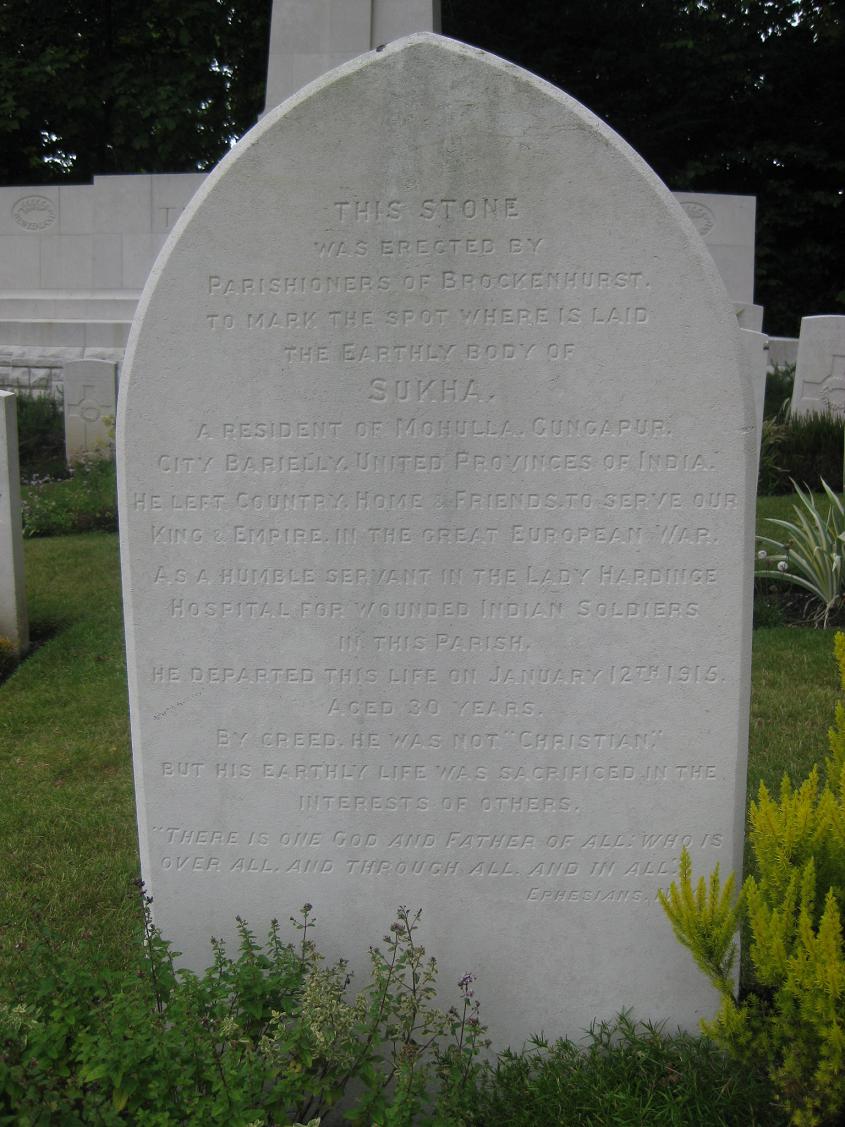

Inscription

This stone was erected by

Parishioners of Brockenhurst

To mark the spot where is laid

The earthly body of

SUKHA

A resident of Mohulla, Gungapur City

Barielly, United Provinces of India.

He left country, home & friends to serve our

King & Empire in the Great European War.

As a humble servant in the LADY HARDINGE HOSPITAL

For wounded Indian soldiers

In this Parish.

He departed this life on January 12th, 1915

Aged 30 years.

By creed, he was not "Christian",

But his earthly life was sacrificed in the

Interests of others.

"There is one God and Father of all: Who is

Over all, and through all, and in all." Ephesians iv-6