Due to his background in leadership roles and passionate work on behalf of the Jewish community and standing up for their rights and representation, on 23 September 1939, during the siege of Warsaw, he was chosen as the head of the city's Judenrat (Jewish council), a group put in the impossible position of being responsible for trying to help their people yet at the same time having to obey Nazi orders that more often than not put their people at a disadvantage. On the fourth of October, shortly after Warsaw had surrendered to the invading Nazi army, he was taken down to Gestapo headquarters and ordered to add 24 more people to the city's Judenrat. Many people resented those in the Judenrat and viewed them as traitors and collaborators, although Czerniakow doesn't appear to have been one of the Judenrat members who abused his power or actively collaborated with the Germans for less than altruistic reasons. He always tried to handle the ghetto's affairs with a minimum of outside involvement, not wanting any Germans to have direct intervention in their affairs. He also actively promoted the schools set up in the ghetto and lobbied on behalf of people whom the Nazis wanted to kill. He also tried to use his position to garner sympathy and respect from the Germans, hoping they would be influenced to treat them with more sensitivity and basic decency, and that they might also give the Judenrat more funding to improve the living conditions. However, there were people who wanted to oust him from his position of power, wanting themselves to be the ones in charge and feeling they deserved it more. None of these attempted coups ever succeeded, as Czerniakow was supported by the Civil Authorities.

On 22 July 1942, the members of the Warsaw Ghetto Judenrat received orders to start preparing lists of people to be deported to the East (where almost all of them were murdered at Treblinka immediately). The only people who would be permitted to remain in the ghetto for the time being were hospital workers, those working in factories, members of the police force and their families, and members of the Judenrat and their families. Frantic to try to protect more people from the deportation lists, Czerniakow spent that entire day obtaining exemptions for a small amount of other people, such as sanitation workers, vocational students, and husbands of women working in the factories. However, he was unable to receive the exemption he was most desperate for, the orphans. Adding insult to injury, the orders went on to state that 6,000 people would be deported each day and would start immediately. The lists would have to be made up by the Judenrat themselves, and the members of the ghetto police force would have to round the people up. Disobedience of any of these orders would result in the immediate murder of 100 hostages, among them employees of the Judenrat and Czerniakow's very own wife. Still desperate to try to stop this, and by now realising just what deportation meant, he tried one last time to plead for the lives of the orphans. This last attempt also resulted in failure, and when he got back to his office, he swallowed a cyanide capsule. The suicide note he left for his wife and the other members of the Judenrat read, "I can no longer bear all this. My act will prove to everyone what is the right thing to do."

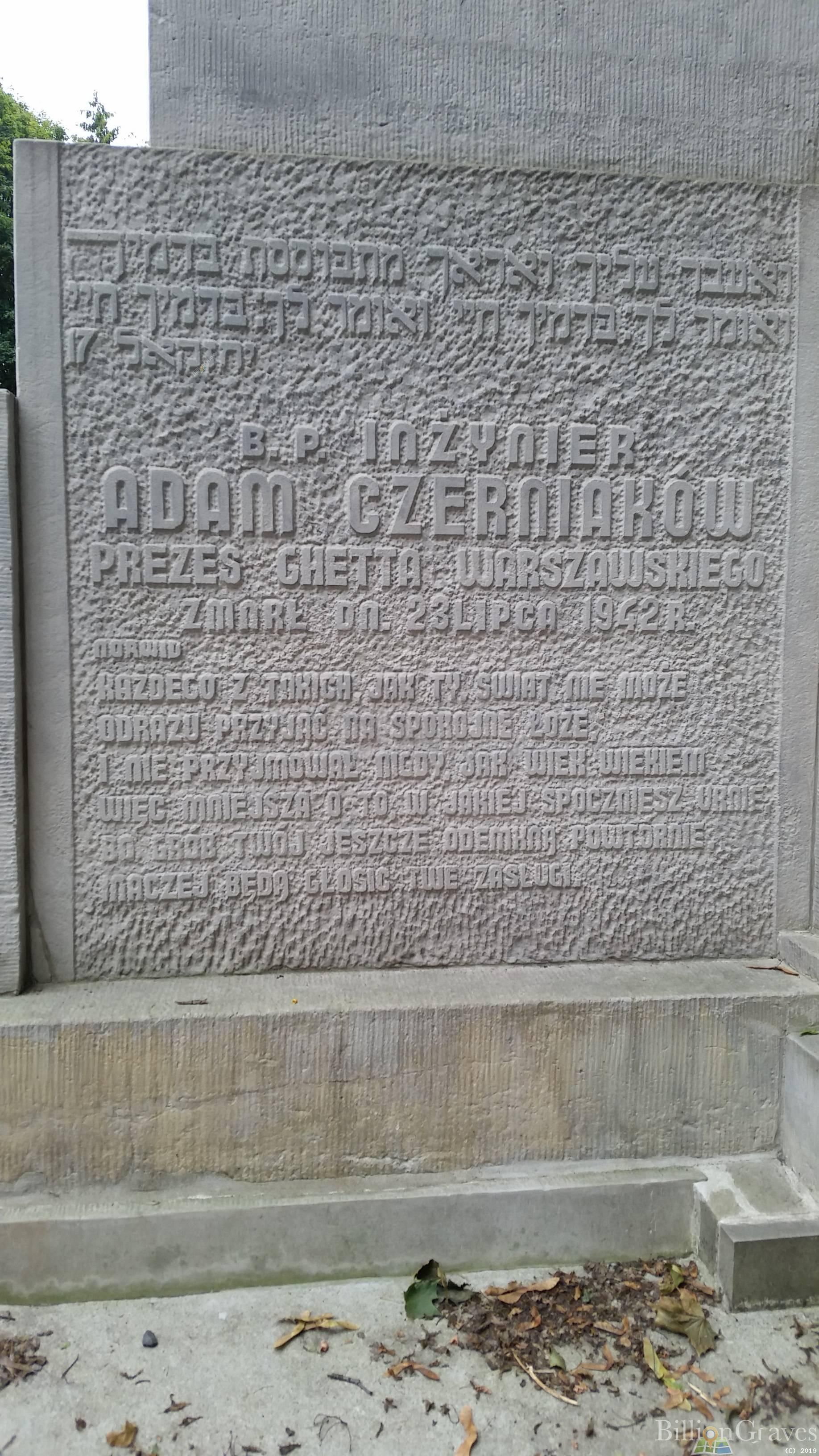

Although normally a suicide is forbidden to be buried in a Jewish cemetery, a special dispensation was made for Czerniakow, and he was buried in the Okopowa Street Jewish Cemetery, Warsaw's largest Jewish cemetery. In 1979 the diary he had kept from 6 September 1939 until his death was published in an English translation, 'The Warsaw Diary of Adam Czerniakow: Prelude to Doom.'

Due to his background in leadership roles and passionate work on behalf of the Jewish community and standing up for their rights and representation, on 23 September 1939, during the siege of Warsaw, he was chosen as the head of the city's Judenrat (Jewish council), a group put in the impossible position of being responsible for trying to help their people yet at the same time having to obey Nazi orders that more often than not put their people at a disadvantage. On the fourth of October, shortly after Warsaw had surrendered to the invading Nazi army, he was taken down to Gestapo headquarters and ordered to add 24 more people to the city's Judenrat. Many people resented those in the Judenrat and viewed them as traitors and collaborators, although Czerniakow doesn't appear to have been one of the Judenrat members who abused his power or actively collaborated with the Germans for less than altruistic reasons. He always tried to handle the ghetto's affairs with a minimum of outside involvement, not wanting any Germans to have direct intervention in their affairs. He also actively promoted the schools set up in the ghetto and lobbied on behalf of people whom the Nazis wanted to kill. He also tried to use his position to garner sympathy and respect from the Germans, hoping they would be influenced to treat them with more sensitivity and basic decency, and that they might also give the Judenrat more funding to improve the living conditions. However, there were people who wanted to oust him from his position of power, wanting themselves to be the ones in charge and feeling they deserved it more. None of these attempted coups ever succeeded, as Czerniakow was supported by the Civil Authorities.

On 22 July 1942, the members of the Warsaw Ghetto Judenrat received orders to start preparing lists of people to be deported to the East (where almost all of them were murdered at Treblinka immediately). The only people who would be permitted to remain in the ghetto for the time being were hospital workers, those working in factories, members of the police force and their families, and members of the Judenrat and their families. Frantic to try to protect more people from the deportation lists, Czerniakow spent that entire day obtaining exemptions for a small amount of other people, such as sanitation workers, vocational students, and husbands of women working in the factories. However, he was unable to receive the exemption he was most desperate for, the orphans. Adding insult to injury, the orders went on to state that 6,000 people would be deported each day and would start immediately. The lists would have to be made up by the Judenrat themselves, and the members of the ghetto police force would have to round the people up. Disobedience of any of these orders would result in the immediate murder of 100 hostages, among them employees of the Judenrat and Czerniakow's very own wife. Still desperate to try to stop this, and by now realising just what deportation meant, he tried one last time to plead for the lives of the orphans. This last attempt also resulted in failure, and when he got back to his office, he swallowed a cyanide capsule. The suicide note he left for his wife and the other members of the Judenrat read, "I can no longer bear all this. My act will prove to everyone what is the right thing to do."

Although normally a suicide is forbidden to be buried in a Jewish cemetery, a special dispensation was made for Czerniakow, and he was buried in the Okopowa Street Jewish Cemetery, Warsaw's largest Jewish cemetery. In 1979 the diary he had kept from 6 September 1939 until his death was published in an English translation, 'The Warsaw Diary of Adam Czerniakow: Prelude to Doom.'