By Kathleen Tinney, Inquirer Staff Writer

POSTED: April 29, 2013

Among East Coast wreck divers, Michael A. deCamp already was a legend when, in June 1966, he got together a dozen buddies to charter a fishing boat and headed for the wild waters south of Nantucket, to the resting place of the Andrea Doria.

The Italian luxury liner had lain there, 250 feet down on her starboard side, since July 26, 1956, after colliding on a foggy night with the Swedish passenger ship Stockholm.

The Doria had been visited by well-heeled explorers, notably department-store scion Peter Gimbel, with an eye to salvaging its riches. But it was Mr. deCamp - in a quarter-inch wet suit against 48-degree water, two tanks with a phone booth's worth of plain air, a finicky double-hose regulator, crude depth gauge, and a watch in a plastic box - who opened the forbidding site to recreational diving.

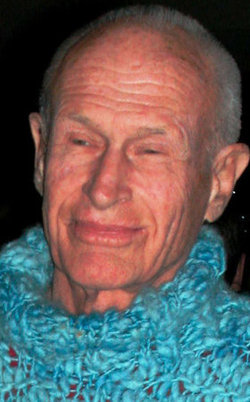

Mr. deCamp, who died Tuesday, April 9, lived most of his 85 years in New Jersey, where he grew up, graduated from Princeton University, and taught science at the Peck School in Morristown.

His heart, though, was offshore, in the briny boneyard to which he began venturing from Point Pleasant Beach in Ocean County about 50 years ago.

To the bold spirit called the "father of East Coast wreck diving," the seafloor was an Elysium of ill-starred vessels. Freighters, tankers, pleasure boats, American subs, German U-boats: Mr. deCamp explored scores of them in thousands of dives, finally and grudgingly beaching himself only at age 82.

The sport exploded around him; active divers nationwide are estimated at one million to three million, with sizable numbers in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. But what distanced him from the pack was photography.

Mr. deCamp surfaced from his dives not with artifacts, but images - up to 250,000, his wife, Wesley, said. Days before he died of cancer, he gave the treasure trove to the New Jersey Maritime Museum in Beach Haven, where it will soon be publicly available.

"It is a phenomenal, lifelong collection that can never be duplicated," said museum president Deb Whitcraft. "Now, it becomes everyone's collection."

Much of what Mr. deCamp preserved on film is indeed gone, reduced by time and the elements to debris piles. When he first dived the Andrea Doria - he made 12 trips - the 697-foot ship was largely intact, with sea anemones creeping up its hull. It has since collapsed.

"I equate him to Mathew Brady," the Civil War pictorial historian, said his close friend Chuck Zimmaro of Harleysville, who was 16 and awestruck when they met.

In the 1960s, "people were writing stories about diving, but it was Mike who came back with the startling pictures," Zimmaro said. "His images brought me and hundreds, if not thousands, of New Jersey and Pennsylvania divers to the sport."

There was no ocean view in Short Hills, the Essex County community where he grew up; or in Princeton, where he received a bachelor's degree in 1949; or in Morristown, where he lived during his 20-year tenure at the Peck School.

Yet, Mr. deCamp once told a reporter, "I'd always wondered . . . what was on the bottom of the ocean."

He found out in 1954 when friend Carleton Ray, associate director of the New York Aquarium, lured the deCamps to the Bahamas to learn to dive. They jury-rigged gear. Ray gave them one lesson: "Don't hold your breath."

"Mike never turned back," said his wife, wed to him since 1950.

At first, they dived together, in Maine, Greece, and Italy. "But he soon left me behind," she said. "He was doing a different kind of diving. Guerrilla diving."

Off the Jersey Shore alone, at least 7,000 wrecks awaited. Some he discovered himself, with tips from captains whose trawl lines had snagged on something suspicious.

Mr. deCamp, however, followed an oil slick to one significant find.

On Thanksgiving 1964, off Manasquan Inlet in an area known as Wreck Valley, the Norwegian tanker Stolt Dagali was cut in two by the Israeli liner Shalom. The stern sank, with 19 crew.

Within days, Mr. deCamp tracked it down, 130 feet under and miles from its reported coordinates. He recovered one body.

The Stolt Dagali now is one of the top diving sites off Jersey, drawing thousands a year.

When not teaching or diving, Mr. deCamp traveled the country lecturing. He wrote for publications such as Skin Diver. He advanced the sport with innovations including the "Jersey upline," used to guide divers to the surface.

He also caught the attention of the National Science Foundation, which sent him to Antarctica for two months in 1965 in a study of Weddell seals. Mr. deCamp dived through a hole cut 10 feet in the ice.

That same year, Capt. Frank Mundus - the model for the shark hunter Quint in Jaws - recruited him as photographer and shark-cage operator for the documentary In the World of Sharks. Mr. deCamp did his work with the cage door open.

"Mike was fearless, but not foolhardy," his wife said. For instance, "he never went inside a wreck," knowing too many people who did not come out.

She allowed, though, she "didn't have much control over him." Her role: "to let Mike be Mike."

In 1984, the deCamps moved to Edenton, N.C. He continued diving, though at 78 he began using - and losing - underwater scooters.

In 2010, in Secaucus, N.J., Mr. deCamp received the first Pioneer of Northeast Diving award at the Beneath the Sea conference.

Everyone knew he loathed fanfare. But for once, Zimmaro said, "he was smiling ear to ear."

Besides his wife, he is survived by a son, John; a daughter, Carly Lober; and three grandchildren.

Mr. deCamp was cremated, with his ashes to be scattered at sea.

Donations may be made to Divers Alert Network, 6 W. Colony Place, Durham, N.C. 27705.

By Kathleen Tinney, Inquirer Staff Writer

POSTED: April 29, 2013

Among East Coast wreck divers, Michael A. deCamp already was a legend when, in June 1966, he got together a dozen buddies to charter a fishing boat and headed for the wild waters south of Nantucket, to the resting place of the Andrea Doria.

The Italian luxury liner had lain there, 250 feet down on her starboard side, since July 26, 1956, after colliding on a foggy night with the Swedish passenger ship Stockholm.

The Doria had been visited by well-heeled explorers, notably department-store scion Peter Gimbel, with an eye to salvaging its riches. But it was Mr. deCamp - in a quarter-inch wet suit against 48-degree water, two tanks with a phone booth's worth of plain air, a finicky double-hose regulator, crude depth gauge, and a watch in a plastic box - who opened the forbidding site to recreational diving.

Mr. deCamp, who died Tuesday, April 9, lived most of his 85 years in New Jersey, where he grew up, graduated from Princeton University, and taught science at the Peck School in Morristown.

His heart, though, was offshore, in the briny boneyard to which he began venturing from Point Pleasant Beach in Ocean County about 50 years ago.

To the bold spirit called the "father of East Coast wreck diving," the seafloor was an Elysium of ill-starred vessels. Freighters, tankers, pleasure boats, American subs, German U-boats: Mr. deCamp explored scores of them in thousands of dives, finally and grudgingly beaching himself only at age 82.

The sport exploded around him; active divers nationwide are estimated at one million to three million, with sizable numbers in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. But what distanced him from the pack was photography.

Mr. deCamp surfaced from his dives not with artifacts, but images - up to 250,000, his wife, Wesley, said. Days before he died of cancer, he gave the treasure trove to the New Jersey Maritime Museum in Beach Haven, where it will soon be publicly available.

"It is a phenomenal, lifelong collection that can never be duplicated," said museum president Deb Whitcraft. "Now, it becomes everyone's collection."

Much of what Mr. deCamp preserved on film is indeed gone, reduced by time and the elements to debris piles. When he first dived the Andrea Doria - he made 12 trips - the 697-foot ship was largely intact, with sea anemones creeping up its hull. It has since collapsed.

"I equate him to Mathew Brady," the Civil War pictorial historian, said his close friend Chuck Zimmaro of Harleysville, who was 16 and awestruck when they met.

In the 1960s, "people were writing stories about diving, but it was Mike who came back with the startling pictures," Zimmaro said. "His images brought me and hundreds, if not thousands, of New Jersey and Pennsylvania divers to the sport."

There was no ocean view in Short Hills, the Essex County community where he grew up; or in Princeton, where he received a bachelor's degree in 1949; or in Morristown, where he lived during his 20-year tenure at the Peck School.

Yet, Mr. deCamp once told a reporter, "I'd always wondered . . . what was on the bottom of the ocean."

He found out in 1954 when friend Carleton Ray, associate director of the New York Aquarium, lured the deCamps to the Bahamas to learn to dive. They jury-rigged gear. Ray gave them one lesson: "Don't hold your breath."

"Mike never turned back," said his wife, wed to him since 1950.

At first, they dived together, in Maine, Greece, and Italy. "But he soon left me behind," she said. "He was doing a different kind of diving. Guerrilla diving."

Off the Jersey Shore alone, at least 7,000 wrecks awaited. Some he discovered himself, with tips from captains whose trawl lines had snagged on something suspicious.

Mr. deCamp, however, followed an oil slick to one significant find.

On Thanksgiving 1964, off Manasquan Inlet in an area known as Wreck Valley, the Norwegian tanker Stolt Dagali was cut in two by the Israeli liner Shalom. The stern sank, with 19 crew.

Within days, Mr. deCamp tracked it down, 130 feet under and miles from its reported coordinates. He recovered one body.

The Stolt Dagali now is one of the top diving sites off Jersey, drawing thousands a year.

When not teaching or diving, Mr. deCamp traveled the country lecturing. He wrote for publications such as Skin Diver. He advanced the sport with innovations including the "Jersey upline," used to guide divers to the surface.

He also caught the attention of the National Science Foundation, which sent him to Antarctica for two months in 1965 in a study of Weddell seals. Mr. deCamp dived through a hole cut 10 feet in the ice.

That same year, Capt. Frank Mundus - the model for the shark hunter Quint in Jaws - recruited him as photographer and shark-cage operator for the documentary In the World of Sharks. Mr. deCamp did his work with the cage door open.

"Mike was fearless, but not foolhardy," his wife said. For instance, "he never went inside a wreck," knowing too many people who did not come out.

She allowed, though, she "didn't have much control over him." Her role: "to let Mike be Mike."

In 1984, the deCamps moved to Edenton, N.C. He continued diving, though at 78 he began using - and losing - underwater scooters.

In 2010, in Secaucus, N.J., Mr. deCamp received the first Pioneer of Northeast Diving award at the Beneath the Sea conference.

Everyone knew he loathed fanfare. But for once, Zimmaro said, "he was smiling ear to ear."

Besides his wife, he is survived by a son, John; a daughter, Carly Lober; and three grandchildren.

Mr. deCamp was cremated, with his ashes to be scattered at sea.

Donations may be made to Divers Alert Network, 6 W. Colony Place, Durham, N.C. 27705.

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement