Elaine was the daughter of Dr. Dave Danforth, a dentist and former Major League Baseball player, and Margaret Oliphant Danforth, a homemaker.

She had learned to fly while an undergraduate at the University of Maryland, College Park, where she earned a bachelor's degree in bacteriology in 1940. She joined the Civil Aeronautics Authority Program and learned to fly Piper Cubs at College Park Airport.

She was accepted into the Women's Airforce Service Pilots — or WASPs. During her career, she flew the AT-6 Texan, PT-17 trainer and BT-13 trainer, and was a co-pilot on the B-17 Flying Fortress.

After her service in WWII, she returned home to Silver Spring, where she lived with her husband, Robert Harmon, a patent attorney, whom she married in 1941. He died in 1965.

She continued flying and enjoyed taking her grandchildren up in small planes.

She never lost her taste for adventure. She continued to travel abroad, played tennis until she was well into her 80s, and went bungee jumping in New Zealand when she turned 80.

She is survived by two sons; two daughters; a sister; 11 other grandchildren; and five great-grandchildren.

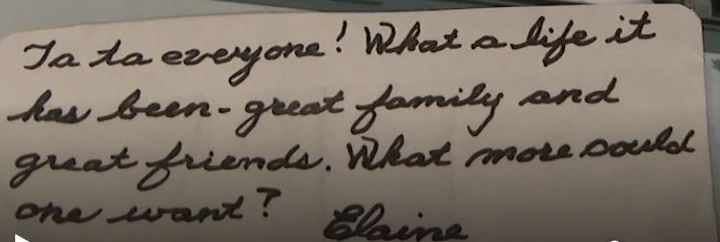

Elaine D. Harmon, who was a member of the Women's Airforce Service Pilots during World War II and later worked to gain veteran status for the pilots, died April 21 of complications from breast cancer at Casey House hospice center in Rockville. She was 95. The daughter of Dr. Dave Danforth, a dentist, and Margaret Oliphant Danforth, a homemaker, Elaine Danforth was born and raised on 34th Street and graduated in 1936 from Eastern High School.She became part of World War II aviation history in 1944 when she was accepted into the Women's Airforce Service Pilots — or WASPs — over the objections of her mother, who considered it "unladylike," said a granddaughter, Erin Miller of Silver Spring. "When I began flight training, the school required at least one parent's signature," Mrs. Harmon told the Air Force Print News in a 2007 interview."Although my father was very supportive of my adventures, my mother was absolutely against the thought of me flying," she said. "So I mailed the letter to my father's office. He promptly signed it and returned it in the next day's mail." She had learned to fly while an undergraduate at the University of Maryland, College Park, where she earned a bachelor's degree in bacteriology in 1940. She joined the Civil Aeronautics Authority Program and learned to fly Piper Cubs at College Park Airport. Gen. Henry H. "Hap" Arnold established the WASP program in 1942. Its purpose was to train women as ferry pilots. One of their jobs was to transport new planes from aircraft manufacturing plants to points where they were shipped or flown overseas. Mrs. Harmon was one of 25,000 women who applied for training. Only 1,830 were accepted, with 1,074 earning their wings. After completing the program, they were assigned to operational duties. Training consisted of six months of ground school and flight training, with a minimum of 500 flight hours. "She became a member of Class 44-9 and trained at Sweetwater, Texas, with a group of women that she always referred to as 'extraordinary,'" said Ms. Miller. After completing her training in 1944 at Avenger Field, she was stationed at Nellis Air Base near Las Vegas. During her career, she flew the AT-6 Texan, PT-17 trainer and BT-13 trainer, and was a co-pilot on the B-17 Flying Fortress. In addition to delivering new planes, WASP pilots trained male pilots, ferried cargo, and dragged targets that were used for target practice. During the war, 38 WASP pilots lost their lives. If a WASP was killed in the line of duty, she was not entitled to a military funeral, and her family was responsible for paying to have her body returned home. They were not authorized to fly a gold star flag that meant a military death of a loved one had occurred, and they were denied veteran status. The WASP program was disbanded in December 1944. After the program ended, Mrs. Harmon returned home to Silver Spring, where she lived with her husband, Robert Harmon, a patent attorney, whom she married in 1941. He died in 1965. All WASP records were classified and sealed for 35 years, which meant little was known of the WASPs' contributions during World War II. "She said the reason the program was kept secret was because the government was afraid if enemy nations found out the USA was 'so desperate' to allow women to fly planes, it would be seen as a weakness," said Ms. Miller. During the 1970s, Mrs. Harmon once again joined with other surviving WASP pilots in an effort aided by Sen. Barry Goldwater, who had been an Air Force pilot, to gain veteran status for them. The culmination of their work was realized in 1977, when President Jimmy Carter signed legislation that granted the WASPs full military status for their wartime service. In 1984, each WASP or a surviving family member was decorated with the World War II Victory Medal, and if they had served for more than a year, the various theater medals. A final honor came for them in 2009 when President Barack Obama, surrounded by WASP pilots including Mrs. Harmon in the Oval Office, signed the bill awarding the Congressional Gold Medal to the pilots. Mrs. Harmon accepted her decoration with other WASP pilots in a ceremony at the Capitol in 2010. Mrs. Harmon continued flying and enjoyed taking her grandchildren up in small planes, her granddaughter said.

Mrs. Harmon attended WASP reunions in Texas and appeared at museum exhibits and memorial dedications. She enjoyed speaking to schoolchildren and others about the WASPs' exploits and the role women played in the war. Until nearly the end of her life, Mrs. Harmon would answer letters requesting autographed pictures of her in her WASP uniform. Mrs. Harmon's WASP memorabilia is on display at the College Park Aviation Museum and on the Denton campus of Texas Women's University, which maintains a WASP collection. She never lost her taste for adventure. She continued to travel abroad, played tennis until she was well into her 80s, and went bungee jumping in New Zealand when she turned 80. She died last year believing she would be inurned at Arlington National Cemetery. The cemetery's superintendent had approved the honor for the WASPs more than a decade earlier. But Harmon did not know that the secretary of the army at the time, John McHugh, overturned the decision about a month before she died. McHugh, concerned about shrinking available space at the cemetery, ruled that the WASPs were eligible for burial only at cemeteries run by the Department of Veterans of Affairs. Arlington is run by the Army. The decision drew outrage. "I couldn't believe it," said Rep. Martha McSally, an Arizona Republican who flew A-10 Warthogs over Iraq and Kuwait.

"These were feisty, brave, adventurous, patriotic women," said McSally, a retired Air Force colonel. "The airplane doesn't care if you're a boy or a girl; they just care if you know how to fly and shoot straight." McSally introduced a bill in the House to overturn McHugh's decision. Sen. Barbara A. Mikulski, a Maryland Democrat, and Sen. Joni Ernst, an Iowa Republican, sponsored similar legislation in the Senate. The bill moved through Congress with unusual speed, winning approval less than five months after introduction. The votes came so quickly, Terry Harmon said, that people thought the family had hired "a big-time K Street firm." In May, Obama signed the legislation, which allows the ashes of the women to be inurned above ground alongside those of other service members. The rules surrounding who may be buried are stricter. And so on Wednesday September 7, 2016, Harmon's ashes were taken off the closet shelf where her family stored them during the ordeal and carried by an honor guard of airmen in dress-blue uniforms to a spot in the southeast corner of the cemetery. The airmen held the flag over Harmon's padauk wood urn during a brief ceremony. A rifle team fired three volleys under an almost cloudless sky. There were tears, but also a sense of celebration among the family. "If the WASPs were good enough to fly and risk their lives for our country, they're good enough for Arlington," Mikulski said in a statement. "This is an honor Lieutenant Elaine Harmon and the WASPs have earned and deserve."

Elaine was the daughter of Dr. Dave Danforth, a dentist and former Major League Baseball player, and Margaret Oliphant Danforth, a homemaker.

She had learned to fly while an undergraduate at the University of Maryland, College Park, where she earned a bachelor's degree in bacteriology in 1940. She joined the Civil Aeronautics Authority Program and learned to fly Piper Cubs at College Park Airport.

She was accepted into the Women's Airforce Service Pilots — or WASPs. During her career, she flew the AT-6 Texan, PT-17 trainer and BT-13 trainer, and was a co-pilot on the B-17 Flying Fortress.

After her service in WWII, she returned home to Silver Spring, where she lived with her husband, Robert Harmon, a patent attorney, whom she married in 1941. He died in 1965.

She continued flying and enjoyed taking her grandchildren up in small planes.

She never lost her taste for adventure. She continued to travel abroad, played tennis until she was well into her 80s, and went bungee jumping in New Zealand when she turned 80.

She is survived by two sons; two daughters; a sister; 11 other grandchildren; and five great-grandchildren.

Elaine D. Harmon, who was a member of the Women's Airforce Service Pilots during World War II and later worked to gain veteran status for the pilots, died April 21 of complications from breast cancer at Casey House hospice center in Rockville. She was 95. The daughter of Dr. Dave Danforth, a dentist, and Margaret Oliphant Danforth, a homemaker, Elaine Danforth was born and raised on 34th Street and graduated in 1936 from Eastern High School.She became part of World War II aviation history in 1944 when she was accepted into the Women's Airforce Service Pilots — or WASPs — over the objections of her mother, who considered it "unladylike," said a granddaughter, Erin Miller of Silver Spring. "When I began flight training, the school required at least one parent's signature," Mrs. Harmon told the Air Force Print News in a 2007 interview."Although my father was very supportive of my adventures, my mother was absolutely against the thought of me flying," she said. "So I mailed the letter to my father's office. He promptly signed it and returned it in the next day's mail." She had learned to fly while an undergraduate at the University of Maryland, College Park, where she earned a bachelor's degree in bacteriology in 1940. She joined the Civil Aeronautics Authority Program and learned to fly Piper Cubs at College Park Airport. Gen. Henry H. "Hap" Arnold established the WASP program in 1942. Its purpose was to train women as ferry pilots. One of their jobs was to transport new planes from aircraft manufacturing plants to points where they were shipped or flown overseas. Mrs. Harmon was one of 25,000 women who applied for training. Only 1,830 were accepted, with 1,074 earning their wings. After completing the program, they were assigned to operational duties. Training consisted of six months of ground school and flight training, with a minimum of 500 flight hours. "She became a member of Class 44-9 and trained at Sweetwater, Texas, with a group of women that she always referred to as 'extraordinary,'" said Ms. Miller. After completing her training in 1944 at Avenger Field, she was stationed at Nellis Air Base near Las Vegas. During her career, she flew the AT-6 Texan, PT-17 trainer and BT-13 trainer, and was a co-pilot on the B-17 Flying Fortress. In addition to delivering new planes, WASP pilots trained male pilots, ferried cargo, and dragged targets that were used for target practice. During the war, 38 WASP pilots lost their lives. If a WASP was killed in the line of duty, she was not entitled to a military funeral, and her family was responsible for paying to have her body returned home. They were not authorized to fly a gold star flag that meant a military death of a loved one had occurred, and they were denied veteran status. The WASP program was disbanded in December 1944. After the program ended, Mrs. Harmon returned home to Silver Spring, where she lived with her husband, Robert Harmon, a patent attorney, whom she married in 1941. He died in 1965. All WASP records were classified and sealed for 35 years, which meant little was known of the WASPs' contributions during World War II. "She said the reason the program was kept secret was because the government was afraid if enemy nations found out the USA was 'so desperate' to allow women to fly planes, it would be seen as a weakness," said Ms. Miller. During the 1970s, Mrs. Harmon once again joined with other surviving WASP pilots in an effort aided by Sen. Barry Goldwater, who had been an Air Force pilot, to gain veteran status for them. The culmination of their work was realized in 1977, when President Jimmy Carter signed legislation that granted the WASPs full military status for their wartime service. In 1984, each WASP or a surviving family member was decorated with the World War II Victory Medal, and if they had served for more than a year, the various theater medals. A final honor came for them in 2009 when President Barack Obama, surrounded by WASP pilots including Mrs. Harmon in the Oval Office, signed the bill awarding the Congressional Gold Medal to the pilots. Mrs. Harmon accepted her decoration with other WASP pilots in a ceremony at the Capitol in 2010. Mrs. Harmon continued flying and enjoyed taking her grandchildren up in small planes, her granddaughter said.

Mrs. Harmon attended WASP reunions in Texas and appeared at museum exhibits and memorial dedications. She enjoyed speaking to schoolchildren and others about the WASPs' exploits and the role women played in the war. Until nearly the end of her life, Mrs. Harmon would answer letters requesting autographed pictures of her in her WASP uniform. Mrs. Harmon's WASP memorabilia is on display at the College Park Aviation Museum and on the Denton campus of Texas Women's University, which maintains a WASP collection. She never lost her taste for adventure. She continued to travel abroad, played tennis until she was well into her 80s, and went bungee jumping in New Zealand when she turned 80. She died last year believing she would be inurned at Arlington National Cemetery. The cemetery's superintendent had approved the honor for the WASPs more than a decade earlier. But Harmon did not know that the secretary of the army at the time, John McHugh, overturned the decision about a month before she died. McHugh, concerned about shrinking available space at the cemetery, ruled that the WASPs were eligible for burial only at cemeteries run by the Department of Veterans of Affairs. Arlington is run by the Army. The decision drew outrage. "I couldn't believe it," said Rep. Martha McSally, an Arizona Republican who flew A-10 Warthogs over Iraq and Kuwait.

"These were feisty, brave, adventurous, patriotic women," said McSally, a retired Air Force colonel. "The airplane doesn't care if you're a boy or a girl; they just care if you know how to fly and shoot straight." McSally introduced a bill in the House to overturn McHugh's decision. Sen. Barbara A. Mikulski, a Maryland Democrat, and Sen. Joni Ernst, an Iowa Republican, sponsored similar legislation in the Senate. The bill moved through Congress with unusual speed, winning approval less than five months after introduction. The votes came so quickly, Terry Harmon said, that people thought the family had hired "a big-time K Street firm." In May, Obama signed the legislation, which allows the ashes of the women to be inurned above ground alongside those of other service members. The rules surrounding who may be buried are stricter. And so on Wednesday September 7, 2016, Harmon's ashes were taken off the closet shelf where her family stored them during the ordeal and carried by an honor guard of airmen in dress-blue uniforms to a spot in the southeast corner of the cemetery. The airmen held the flag over Harmon's padauk wood urn during a brief ceremony. A rifle team fired three volleys under an almost cloudless sky. There were tears, but also a sense of celebration among the family. "If the WASPs were good enough to fly and risk their lives for our country, they're good enough for Arlington," Mikulski said in a statement. "This is an honor Lieutenant Elaine Harmon and the WASPs have earned and deserve."

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement