He was born on Long Island, Nassau County, New York to Etta Rose (Smith) of New York City and Chief Gunner's Mate John Halmar Rosloof, USN, a naturalized American citizen from Finland who enlisted in the Navy in 1894 and went on to serve for 34 years. The oldest of two sons, James was born on his father's fifty-second birthday in 1924. During the Spanish American War, John was a gunner's mate third class on the USS New York, flagship of Admiral William T. Sampson. Chief John Rosloof retired from active duty in 1928, several years after his World War I service and went to work as a gardener for the New York State Parks. James had two older sisters, Evelyn and Margaret and one younger brother, John. He graduated from Hempstead High School, Class of '42, on Long Island, NY where he lived prior to entering the Army.

Inducted on 24 October 1942 at New York City, the enlistment record noted him as single, without dependents. James was sent to the Infantry Replacement Training Center at Camp Croft near Spartanburg, South Carolina, where he reported on November 16, 1942. Assigned to Company "A", 31st Inf. Training Batt., he completed his training as "an Infantryman of a Rifle Company" on 13 February 1943.

James was assigned to the 7th Infantry Regiment, one of the oldest and most highly decorated Army regiments, known as the "Cottonbalers", for the unit's historic service in 1815 at the Battle of New Orleans under Gen. Andrew Jackson when its soldiers held positions behind a breastwork of cotton bales during the British attack.

The 7th was part of the 3rd Infantry Division, formed in 1917 and known as the "Marne Division" from its World War I service when the 7th Machine Gun Battalion of the 3rd Division rushed to Château-Thierry amid retreating French troops and held the Germans back at the Marne River. While surrounding units retreated, the 3rd Infantry Division, including the 30th and 38th Infantry Regiments, remained steadfast throughout the Second Battle of the Marne, and so earned its nickname, the "Rock of the Marne".

James landed with the 7th at Tunisia in 1943 and his service represented four campaign stars- Tunisia, Sicily, Naples-Foggia and Anzio.

Per Army General Order No 41, HQ Third Infantry Division, dated 23 March 1944, PFC Rosloof was awarded the "Silver Star" for combat service on January 31, 1944. His citation reads, "For gallantry in action. On 31 January 1944 at *** hours, near ***(Ponte Rotto), Italy, Private First Class ROSLOOF put his machine gun into action in the face of heavy small arms fire from the enemy who were only fifty yards away. Selecting an exposed position in order to get a good field of fire, he delivered a heavy volume of fire into the enemy until their resistance was subdued. Again at ***, ignoring enemy fire which missed him by inches, he plunged into a fire fight with the enemy, again placing his weapon in an exposed position in order to obtain enfilade fire where he remained until the enemy was annihilated. Residence at enlistment, Hempstead, New York."

The actions of the 3rd Battalion, 7th Infantry Regiment that day are summarized as follows:

Forming the left prong of the 3d Division attack, the 7th Infantry, under the command of Col. Harry B. Sherman, was to cut Highway No. 7 above Cisterna. The 1st Battalion made a long night match to the line of departure and then at 0200, 30 January, launched its attack north along Le Mole Creek to cut the highway before daylight; the 2d Battalion's attack up the Crocetta-Cisterna road did not get started until 1115. The day before the attack the 30th Infantry had still been fighting for the area designated as the 1st Battalion's line of departure.

Consequently, Lt. Col. Frank M. Izenour, the 1st Battalion commander, had been unable to make a detailed reconnaissance of the route of advance and was forced to rely mainly on air photographs. Before the 1st Battalion had advanced very far, the troops found that what had appeared to be evenly spaced hedgerows in the aerial photographs were actually 20-foot drainage ditches overgrown with briars. These barriers greatly hampered the night movement and the tanks, which were unable to cross them in the dark, had to be left behind. The infantry had pressed forward a mile and a half across the fields on both sides of the creek when suddenly a burst of German flares starkly outlined the troops against the dark ground. All around them the enemy opened fire. Daylight revealed the battalion caught in a small pocket formed by low knolls to the front, left, and right rear. From his positions on the three knolls the enemy poured down automatic fire. The men dived for cover of the ditches, but each ditch seemed enfiladed by German machine guns.

The battalion suffered heavy losses; Colonel Izenour and about 150 others, men and officers, were hit. Capt. William P. Athas of the heavy weapons company hastily set up four machine guns, and under their protecting fire the riflemen deployed and drove the Germans from the hill to the right rear. During the day, 246 men of the scattered battalion filtered through to rally on this knoll, Maj. Frank Sinsel was sent forward to take command of the battalion and, after daylight, tanks managed to negotiate the ditches and came up in support. All day the 1st Battalion, too weak to attack, held its ground under the battering of enemy artillery and mortar fire. Reinforcements were sent up through the ditches that night, but the enemy, with guns sited accurately on the ditches, subjected the troops moving up to heavy shell fire.

The 2nd Battalion attack up the road toward Cisterna was also delayed. Its tanks were unable to move up through the smoke and artillery fire laid down by supporting units. When the troops finally crossed the line of departure they were thrown back almost immediately by a unit of the 1st Parachute Division, which had moved in the night before and dug in around the road junction south of Ponte Rotto. To renew the attack that afternoon, Colonel Sherman added his reserve 3rd Battalion. He ordered Maj. William B. Rosson, the battalion commander, to clean up the road junction from the south and go on to the high ground overlooking Ponte Rotto. The Sherman tanks and M-10 tank destroyers operating with the battalion rumbled up over the gravel road, systematically demolishing each German-held farmhouse and haystack barring the way. Behind the screen of armor and intensive artillery and mortar concentrations, the infantry cleared the road junction from the south and pushed on to seize their objective, the knoll above Ponte Rotto, by daylight on 31 January. In the first day's assault the 7th Infantry had gained about half the distance to Cisterna."

James was promoted to sergeant sometime after his gallantry on 31 January 1944. His battalion commander, Major William B. Rosson was awarded the nation's second highest combat award for heroism, the Distinguished Service Cross, for his actions on that same day. Ironically, the next day, the American forces reached the closest point to their objective, the German occupied town of Cisterna that they would have for the next four months, as the enemy rushed in reinforcements and repulsed the Americans back to the beachhead line.

"In direct defense of the major stronghold of Cisterna, the Germans had constructed their most formidable defenses, controlled from a regimental command post located in a wine cellar deep underneath a large building in the center of the town. Other cellars and numerous tunnels honeycombed the ground beneath the town, sheltering its garrison from the 3d Division's preparatory artillery fire and aerial bombardment. When those fires ceased, the Germans quickly emerged to man firing positions from which they could contest every foot of ground.

The 7th Infantry commander, Colonel Omohundro, was to send two battalions abreast in a northeasterly direction along the axis of the Isola Bella-Cisterna road to break through the enemy defenses south of Cisterna and draw up to the town. That accomplished, Omohundro, on division order, was to send his reserve battalion to take the settlement of La Villa, on the railroad a mile northwest of Cisterna, and then seize a ridge just east of La Villa, cut Highway 7 in the vicinity of the Cisterna cemetery, and occupy a portion of the X-Y phase line. The remainder of the regiment was, on division order, to clear the Germans from the rubble of Cisterna. A company each from the 751st Tank Battalion and the 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion, as well as a battery from the 10th Field Artillery Battalion (105-mm. howitzers, towed), were to be in direct support of the regiment throughout.

No sooner had leading troops of the 7th Infantry's 3d Battalion crossed their line of departure (about three miles southwest of Cisterna) at 0630 than automatic weapons fire from two positions about half a mile northeast of Isola Bella drove them to cover. Two and a half hours after the attack began the two advance companies were still, in the words of Omohundro's S-3, "pinned down." To that report General O'Daniel growled, "We have no such words in our vocabulary now." The division commander added threateningly in words meant more for Omohundro than his harried S-3, "You're supposed to be at the railroad track by noon. You'll get a bonus if you do, something else if you don't." What Omohundro's infantrymen most needed at that point was close-in fire support, but an uncleared antitank mine field kept the attached medium tank platoon and a platoon of tank destroyers too far away to have effect.

To get the attack moving again, a slow, painstaking, and costly infantry advance in the face of enemy fire seemed the only way. Taking advantage of every scrap of cover and concealment, especially numerous drainage ditches, the 3d Battalion, with Company L leading, laboriously started to move. It took the men three hours to advance one mile to within grenade-throwing range of the enemy strongpoint that had held up the attack all morning. Unable or unwilling to resist once Company L got that close, sixteen surviving Germans raised their hands in surrender. Their capitulation enabled Company L to move quickly onto its first objective, the Colle Monaco, a low rise about a quarter of mile northeast of Isola Bella, while Company I in the meantime slipped around to the left to seize a nose of adjacent high ground 500 yards away. Moving too far to the west, Company I encountered a storm of enemy fire that forced the men to take such cover as they could find. The battalion commander committed Company K on Company I's right, but that move proved of little help after enemy fire killed first the company commander (1st Lt. James S. McCracken) and later the officer that replaced him. (1st Lt. Ralph Rocchiccioli) By mid-afternoon, the 3d Battalion had penetrated the German position to a depth of almost a mile, but, in doing so, had incurred such heavy casualties that the momentum of its attack was lost."

James was "Killed In Action" that day, 23 May 1944, the first day of "Operation Buffalo", the break-out attack from Anzio to capture Cisterna that began the 3rd Division's advance to Rome. One of the men in his company, PFC Michael J. Maszezak , advancing 30' feet from him, observed that SGT Rosloof was hit by a white phosphorous round, causing nearly instantaneous fatal burns. Maszezak was also wounded in the action by shell fragments for which he was hospitalized. SGT Rosloof's remains were not identified and recovered until months later. He was one of 54 "Cotton Balers" killed that day and more than 950 dead in the 3rd Division- the most casualties to an Army division in a single day during World War II.

Cisterna was ultimately captured by the American troops on the 3rd day of battle, 25 May 1944. Initially declared "missing in action", it was not until late July 1944 that his parents received the dreaded word that he had been killed in action on 23 May 1944. James was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart that was presented to his family in August 1944. Ironically, exactly one week before his death, on 16 May 1944, his hometown newspaper, the Nassau Daily Review, published the Army press release of his award of the Silver Star on its front page; however, with a picture of a different soldier that the Army public affairs office had erroneously provided.

SGT Rosloof was originally interred in Nettuno, Italy and his remains were later shipped back to the United States on the S.S. Carroll Victory. He was repatriated here at Long Island National Cemetery on 11 August 1948.

Who for the Union fought and bled, though passing on, is never dead.

He was born on Long Island, Nassau County, New York to Etta Rose (Smith) of New York City and Chief Gunner's Mate John Halmar Rosloof, USN, a naturalized American citizen from Finland who enlisted in the Navy in 1894 and went on to serve for 34 years. The oldest of two sons, James was born on his father's fifty-second birthday in 1924. During the Spanish American War, John was a gunner's mate third class on the USS New York, flagship of Admiral William T. Sampson. Chief John Rosloof retired from active duty in 1928, several years after his World War I service and went to work as a gardener for the New York State Parks. James had two older sisters, Evelyn and Margaret and one younger brother, John. He graduated from Hempstead High School, Class of '42, on Long Island, NY where he lived prior to entering the Army.

Inducted on 24 October 1942 at New York City, the enlistment record noted him as single, without dependents. James was sent to the Infantry Replacement Training Center at Camp Croft near Spartanburg, South Carolina, where he reported on November 16, 1942. Assigned to Company "A", 31st Inf. Training Batt., he completed his training as "an Infantryman of a Rifle Company" on 13 February 1943.

James was assigned to the 7th Infantry Regiment, one of the oldest and most highly decorated Army regiments, known as the "Cottonbalers", for the unit's historic service in 1815 at the Battle of New Orleans under Gen. Andrew Jackson when its soldiers held positions behind a breastwork of cotton bales during the British attack.

The 7th was part of the 3rd Infantry Division, formed in 1917 and known as the "Marne Division" from its World War I service when the 7th Machine Gun Battalion of the 3rd Division rushed to Château-Thierry amid retreating French troops and held the Germans back at the Marne River. While surrounding units retreated, the 3rd Infantry Division, including the 30th and 38th Infantry Regiments, remained steadfast throughout the Second Battle of the Marne, and so earned its nickname, the "Rock of the Marne".

James landed with the 7th at Tunisia in 1943 and his service represented four campaign stars- Tunisia, Sicily, Naples-Foggia and Anzio.

Per Army General Order No 41, HQ Third Infantry Division, dated 23 March 1944, PFC Rosloof was awarded the "Silver Star" for combat service on January 31, 1944. His citation reads, "For gallantry in action. On 31 January 1944 at *** hours, near ***(Ponte Rotto), Italy, Private First Class ROSLOOF put his machine gun into action in the face of heavy small arms fire from the enemy who were only fifty yards away. Selecting an exposed position in order to get a good field of fire, he delivered a heavy volume of fire into the enemy until their resistance was subdued. Again at ***, ignoring enemy fire which missed him by inches, he plunged into a fire fight with the enemy, again placing his weapon in an exposed position in order to obtain enfilade fire where he remained until the enemy was annihilated. Residence at enlistment, Hempstead, New York."

The actions of the 3rd Battalion, 7th Infantry Regiment that day are summarized as follows:

Forming the left prong of the 3d Division attack, the 7th Infantry, under the command of Col. Harry B. Sherman, was to cut Highway No. 7 above Cisterna. The 1st Battalion made a long night match to the line of departure and then at 0200, 30 January, launched its attack north along Le Mole Creek to cut the highway before daylight; the 2d Battalion's attack up the Crocetta-Cisterna road did not get started until 1115. The day before the attack the 30th Infantry had still been fighting for the area designated as the 1st Battalion's line of departure.

Consequently, Lt. Col. Frank M. Izenour, the 1st Battalion commander, had been unable to make a detailed reconnaissance of the route of advance and was forced to rely mainly on air photographs. Before the 1st Battalion had advanced very far, the troops found that what had appeared to be evenly spaced hedgerows in the aerial photographs were actually 20-foot drainage ditches overgrown with briars. These barriers greatly hampered the night movement and the tanks, which were unable to cross them in the dark, had to be left behind. The infantry had pressed forward a mile and a half across the fields on both sides of the creek when suddenly a burst of German flares starkly outlined the troops against the dark ground. All around them the enemy opened fire. Daylight revealed the battalion caught in a small pocket formed by low knolls to the front, left, and right rear. From his positions on the three knolls the enemy poured down automatic fire. The men dived for cover of the ditches, but each ditch seemed enfiladed by German machine guns.

The battalion suffered heavy losses; Colonel Izenour and about 150 others, men and officers, were hit. Capt. William P. Athas of the heavy weapons company hastily set up four machine guns, and under their protecting fire the riflemen deployed and drove the Germans from the hill to the right rear. During the day, 246 men of the scattered battalion filtered through to rally on this knoll, Maj. Frank Sinsel was sent forward to take command of the battalion and, after daylight, tanks managed to negotiate the ditches and came up in support. All day the 1st Battalion, too weak to attack, held its ground under the battering of enemy artillery and mortar fire. Reinforcements were sent up through the ditches that night, but the enemy, with guns sited accurately on the ditches, subjected the troops moving up to heavy shell fire.

The 2nd Battalion attack up the road toward Cisterna was also delayed. Its tanks were unable to move up through the smoke and artillery fire laid down by supporting units. When the troops finally crossed the line of departure they were thrown back almost immediately by a unit of the 1st Parachute Division, which had moved in the night before and dug in around the road junction south of Ponte Rotto. To renew the attack that afternoon, Colonel Sherman added his reserve 3rd Battalion. He ordered Maj. William B. Rosson, the battalion commander, to clean up the road junction from the south and go on to the high ground overlooking Ponte Rotto. The Sherman tanks and M-10 tank destroyers operating with the battalion rumbled up over the gravel road, systematically demolishing each German-held farmhouse and haystack barring the way. Behind the screen of armor and intensive artillery and mortar concentrations, the infantry cleared the road junction from the south and pushed on to seize their objective, the knoll above Ponte Rotto, by daylight on 31 January. In the first day's assault the 7th Infantry had gained about half the distance to Cisterna."

James was promoted to sergeant sometime after his gallantry on 31 January 1944. His battalion commander, Major William B. Rosson was awarded the nation's second highest combat award for heroism, the Distinguished Service Cross, for his actions on that same day. Ironically, the next day, the American forces reached the closest point to their objective, the German occupied town of Cisterna that they would have for the next four months, as the enemy rushed in reinforcements and repulsed the Americans back to the beachhead line.

"In direct defense of the major stronghold of Cisterna, the Germans had constructed their most formidable defenses, controlled from a regimental command post located in a wine cellar deep underneath a large building in the center of the town. Other cellars and numerous tunnels honeycombed the ground beneath the town, sheltering its garrison from the 3d Division's preparatory artillery fire and aerial bombardment. When those fires ceased, the Germans quickly emerged to man firing positions from which they could contest every foot of ground.

The 7th Infantry commander, Colonel Omohundro, was to send two battalions abreast in a northeasterly direction along the axis of the Isola Bella-Cisterna road to break through the enemy defenses south of Cisterna and draw up to the town. That accomplished, Omohundro, on division order, was to send his reserve battalion to take the settlement of La Villa, on the railroad a mile northwest of Cisterna, and then seize a ridge just east of La Villa, cut Highway 7 in the vicinity of the Cisterna cemetery, and occupy a portion of the X-Y phase line. The remainder of the regiment was, on division order, to clear the Germans from the rubble of Cisterna. A company each from the 751st Tank Battalion and the 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion, as well as a battery from the 10th Field Artillery Battalion (105-mm. howitzers, towed), were to be in direct support of the regiment throughout.

No sooner had leading troops of the 7th Infantry's 3d Battalion crossed their line of departure (about three miles southwest of Cisterna) at 0630 than automatic weapons fire from two positions about half a mile northeast of Isola Bella drove them to cover. Two and a half hours after the attack began the two advance companies were still, in the words of Omohundro's S-3, "pinned down." To that report General O'Daniel growled, "We have no such words in our vocabulary now." The division commander added threateningly in words meant more for Omohundro than his harried S-3, "You're supposed to be at the railroad track by noon. You'll get a bonus if you do, something else if you don't." What Omohundro's infantrymen most needed at that point was close-in fire support, but an uncleared antitank mine field kept the attached medium tank platoon and a platoon of tank destroyers too far away to have effect.

To get the attack moving again, a slow, painstaking, and costly infantry advance in the face of enemy fire seemed the only way. Taking advantage of every scrap of cover and concealment, especially numerous drainage ditches, the 3d Battalion, with Company L leading, laboriously started to move. It took the men three hours to advance one mile to within grenade-throwing range of the enemy strongpoint that had held up the attack all morning. Unable or unwilling to resist once Company L got that close, sixteen surviving Germans raised their hands in surrender. Their capitulation enabled Company L to move quickly onto its first objective, the Colle Monaco, a low rise about a quarter of mile northeast of Isola Bella, while Company I in the meantime slipped around to the left to seize a nose of adjacent high ground 500 yards away. Moving too far to the west, Company I encountered a storm of enemy fire that forced the men to take such cover as they could find. The battalion commander committed Company K on Company I's right, but that move proved of little help after enemy fire killed first the company commander (1st Lt. James S. McCracken) and later the officer that replaced him. (1st Lt. Ralph Rocchiccioli) By mid-afternoon, the 3d Battalion had penetrated the German position to a depth of almost a mile, but, in doing so, had incurred such heavy casualties that the momentum of its attack was lost."

James was "Killed In Action" that day, 23 May 1944, the first day of "Operation Buffalo", the break-out attack from Anzio to capture Cisterna that began the 3rd Division's advance to Rome. One of the men in his company, PFC Michael J. Maszezak , advancing 30' feet from him, observed that SGT Rosloof was hit by a white phosphorous round, causing nearly instantaneous fatal burns. Maszezak was also wounded in the action by shell fragments for which he was hospitalized. SGT Rosloof's remains were not identified and recovered until months later. He was one of 54 "Cotton Balers" killed that day and more than 950 dead in the 3rd Division- the most casualties to an Army division in a single day during World War II.

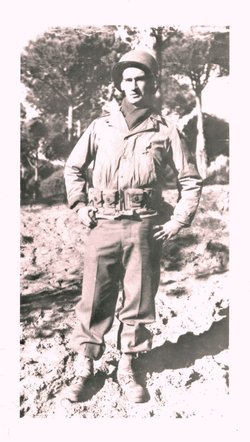

Cisterna was ultimately captured by the American troops on the 3rd day of battle, 25 May 1944. Initially declared "missing in action", it was not until late July 1944 that his parents received the dreaded word that he had been killed in action on 23 May 1944. James was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart that was presented to his family in August 1944. Ironically, exactly one week before his death, on 16 May 1944, his hometown newspaper, the Nassau Daily Review, published the Army press release of his award of the Silver Star on its front page; however, with a picture of a different soldier that the Army public affairs office had erroneously provided.

SGT Rosloof was originally interred in Nettuno, Italy and his remains were later shipped back to the United States on the S.S. Carroll Victory. He was repatriated here at Long Island National Cemetery on 11 August 1948.

Who for the Union fought and bled, though passing on, is never dead.

Bio by: Russ Pickett

Inscription

SGT 7 INF

3 INF DIV

WORLD WAR II

Family Members

Flowers

Advertisement

See more Rosloof memorials in:

Advertisement