His body was, as the coroner's register put it, "in a supine position" and showed signs of slight rigor mortis. Cavanaugh wore underwear, shoes, socks, pants, a shirt and a jacket. In his pocket was $21.12 and on his wrist a Timex.

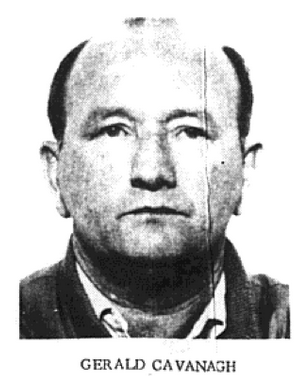

As befits a man initially identified as John Doe #7, very little is known about Cavanaugh. He was born in Canada on March 2, 1923, and lived in San Francisco. A photo that ran in the San Francisco Sentinel after his death shows that he was balding.

He worked in a mattress factory. He was five-foot-eight and weighed 220 pounds. He was Catholic. "Never married," wrote the coroner.

Cavanaugh was the first victim in a string of homicides that, to this day, remain unsolved. From January 1974 to September 1975, The Doodler—or, as he was sometimes known, the Black Doodler, on account of his skin color—caught the eye of the Castro's bar patrons by drawing caricatures and cartoons of them.f

Amused, flattered, perhaps titillated by the attention, man after man would leave the bar with their killer for a more secluded, intimate spot. Once they were alone, the men were stabbed and their bodies left on waterfronts and in parks.

To the extent the case has been written about, the Doodler has been credited with fourteen victims. One encounters this figure in the era's press accounts and books of recent vintage. But it is far more likely there were, in fact, five or six. (The larger figure may be due to the frequency with which gay men were murdered in those years; it's possible that several distinct cases were conflated and the Doodler given too much credit.)

Five men were contemporaneously identified in the newspapers as Doodler victims, but the count shouldn't be considered definitive. It's a fool's errand to say any single victim is definitely the work of the Doodler, or to rule out the possibility of others. As a veteran detective told me, "Anyone in my position who tells you otherwise, especially when there hasn't even been an indictment, is either untrustworthy or lying."

Forty years after the fact, the story of the Doodler killings has not been even cursorily told. Unlike cases with similar body counts—the Zodiac Killer and David Berkowitz, for example—this one was quickly forgotten.

It was, perhaps, somewhat a matter of timing. When the killings began, it had been just a year since the American Psychiatric Association Board of Trustees ceased classifying homosexuality as a disorder.

Most media outlets, just maybe, did not consider gay men sufficiently sympathetic to rate coverage. And then, four and half years after the killings ended, San Francisco's own Ken Horne, a ballet school dropout, was reported to the Centers for Disease Control with Kaposi's Sarcoma. Five murdered men would become, relative to what followed, a statistical blip.

His body was, as the coroner's register put it, "in a supine position" and showed signs of slight rigor mortis. Cavanaugh wore underwear, shoes, socks, pants, a shirt and a jacket. In his pocket was $21.12 and on his wrist a Timex.

As befits a man initially identified as John Doe #7, very little is known about Cavanaugh. He was born in Canada on March 2, 1923, and lived in San Francisco. A photo that ran in the San Francisco Sentinel after his death shows that he was balding.

He worked in a mattress factory. He was five-foot-eight and weighed 220 pounds. He was Catholic. "Never married," wrote the coroner.

Cavanaugh was the first victim in a string of homicides that, to this day, remain unsolved. From January 1974 to September 1975, The Doodler—or, as he was sometimes known, the Black Doodler, on account of his skin color—caught the eye of the Castro's bar patrons by drawing caricatures and cartoons of them.f

Amused, flattered, perhaps titillated by the attention, man after man would leave the bar with their killer for a more secluded, intimate spot. Once they were alone, the men were stabbed and their bodies left on waterfronts and in parks.

To the extent the case has been written about, the Doodler has been credited with fourteen victims. One encounters this figure in the era's press accounts and books of recent vintage. But it is far more likely there were, in fact, five or six. (The larger figure may be due to the frequency with which gay men were murdered in those years; it's possible that several distinct cases were conflated and the Doodler given too much credit.)

Five men were contemporaneously identified in the newspapers as Doodler victims, but the count shouldn't be considered definitive. It's a fool's errand to say any single victim is definitely the work of the Doodler, or to rule out the possibility of others. As a veteran detective told me, "Anyone in my position who tells you otherwise, especially when there hasn't even been an indictment, is either untrustworthy or lying."

Forty years after the fact, the story of the Doodler killings has not been even cursorily told. Unlike cases with similar body counts—the Zodiac Killer and David Berkowitz, for example—this one was quickly forgotten.

It was, perhaps, somewhat a matter of timing. When the killings began, it had been just a year since the American Psychiatric Association Board of Trustees ceased classifying homosexuality as a disorder.

Most media outlets, just maybe, did not consider gay men sufficiently sympathetic to rate coverage. And then, four and half years after the killings ended, San Francisco's own Ken Horne, a ballet school dropout, was reported to the Centers for Disease Control with Kaposi's Sarcoma. Five murdered men would become, relative to what followed, a statistical blip.