Al's parents were:

George Ballard, b. Jul. 1890 in Nelson County, KY. and d. Aug. 1973 in Louisville, Jefferson County, KY. &

Minnie J. Cummins, b. Nov. 1891 in Whitley County, KY. and d. Feb. 18, 1981 in Louisville, Jefferson County, KY.

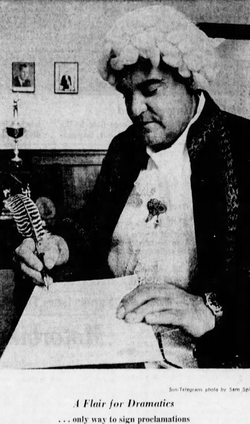

The Sun-Telegram (San Bernardino, CA.), P. 1, Col. 4-6 and P. 19, Col. 1-6

Sun., May 2, 1971

Six Stormy Years in Office Reviewed

The Many Faces of Mayor Ballard

SAN BERNARDINO - We first met a couple of weeks after he was sworn into office for the first time. There had been a reorganization of news beats and I got City Hall.

"I'll never forget his first words to me: "I can't fight a girl."

Mayor Alvin Curtis Ballard, a farm boy from Kentucky, learns fast.

He soon became the fuel that made my typewriter go. He was nonstop hot copy.

A few years later, one of his aides chanced to be extolling his boss' virtues at a political luncheon and prophesied that people would still be talking about Al Ballard "50 years from now."

He said it as a matter of fact. Everyone who listened believed. They were learning to praise or to be confounded by the Ballard mystique. That's because the hard-driving ex-fireman who said he was "kidded into running" for the city's highest office, was well on his way to making a name for himself, not only in the city that he was commanding like the ringmaster for a one-man show, but across the country.

It's difficult to "live" with a mayor for six years and not learn to love him in a unique kind of way. In his dealings with the press, he likes to be close, but not too close; frank but not too frank.

A reporter-mayor relationship with Al Ballard can perhaps be summed up with the lines of a popular mouthwash commercial, "I hate it! But I love it!"

It didn't take long for reporters to realize that Ballard was probably way up there in the ratings against "Laugh-In" when City Council meetings and the TV show shared Monday night prime time.

Spectators sometimes filled the chamber. Reporters secretly wondered if he hadn't personally gone out to gather up all whom he could find. The larger audiences were usually pro-Ballard. They always cheered and booed in the appropriate places.

But those days came later. Early in his career, the regular 2 p.m. daily interviews were more like show-and-tell time in the big office at City Hall.

The mayor had been a city fireman for 18 1/2 years and before that was involved in a variety of businesses - 13 in all, he likes to tell people - before he was elected to his first term by outpolling incumbent Donald G. (Bud) Mauldin by 1,288 votes in 1965.

The newness of the office was apparent to Ballard in those early days. He would sometimes ask, "What do you think?" When asked how he was going to handle a problem. He really wanted to know.

He came to know many people and had many friends in many walks of life through his past occupations as a moonlighting weed abatement contractor, a plumber, a plasterer, service station owner and home builder.

But politics was a new field. Adaptable Al Ballard, who left the Catholic school he was attending in Louisville, Ky., to come to California when he was 17, learns fast.

The metamorphosis was rapid. Those daily meetings soon were no longer naive show-and-tell sessions. Ballard began keeping his guard up. He sometimes was defensive about some matters that, to the public, didn't appear to be in need of defense.

Maybe he learned to be that way because of his trips to Washington, D. C. It wasn't long after Ballard was in office that he learned there was "gold" on Capitol Hill and all he had to do was be there first with the best program and he could bring some home with him to San Bernardino.

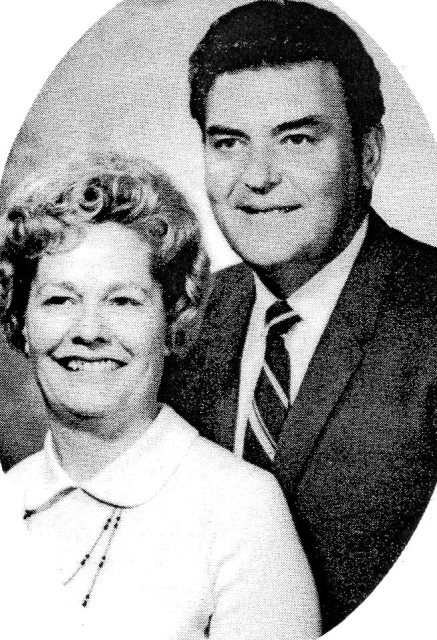

Then he would sit at his desk with his constant cup of coffee looking like a cigar-loving Teddy bear while he told about "wining and dining" the people in Washington by night and proving to them he needed federal aid to keep his city on the move by day.

Sometimes Ballard throws words in terse, staccato sentences that land like body blows, these accompanied by fierce looks and a twist of the mouth.

He doesn't keep anything resembling "regular" hours now for talking to the press. That practice died quickly as the pace of the office grew.

More often than not, I found myself scrambling for a pencil when the Mayor suddenly burst into quotability while walking briskly down the street or when he impulsively picked up the car telephone and dialed my number.

This man of many moods changes them like a chameleon changes his colors. I soon learned not to be shocked when he whispered a confidence and then said with believability, "You print one word of that, and I'll kill you!"

Later he plants a gentle kiss on his 17-year-old daughter's cheek.

This is the coexistent tenderness and coarseness that make up the paradoxical Ballard Mystique.

A large man, Ballard stands 5 feet 11 and sometimes nears the 200 mark on the scales. Because of the constant rounds of dinner meetings and party invitations, his wife Emma must keep after him to watch his diet.

Both of them switched to high protein fare just before they visited Tachikawa, Japan, last year. Tachikawa is one of San Bernardino's sister cities.

Since he decided not to seek a fourth term in office, the mayor hasn't been watching the scales, however. In fact, he's taking on a new look. When he first came into office, he wore only dark blue suits, white shirts, conservative ties.

The new Ballard goes for mustard-colored dress shirts, five-inch wide ties with contrasting prints and, his latest addition, wire-frame, tinted, bifocal glasses.

Ballard leaves office on May 10, turning his gavel over to W. R. Holcomb, a wiry, blue-eyed lawyer who is a native of San Bernardino.

Straightening the spectacles and brushing back a shock of black, tousled hair, he grins, "I can wear anything I want now."

A thorn in the side to some; a benevolent friend to others. A "demonic slob" to one of his foes; the "person who was closest to me, next to my father," to J. T. Winstead, the city administrator Ballard hired as an aide when he was only 26 years old. Ballard truly will be remembered.

He said the other day that he is "worth $100,000 less than when I first came into office." This amount, amassed from his various businesses, which include the Fed discount service station and part ownership in a wed side medical building, he spent while in office.

"It's rough," he said. "In all these years, I've had to spend about $120 a day just in pocket money. For the first time since I've been in office, I've had to depend on my check (his mayor's salary of $600 per month)."

Ballard, who ran for Congress as a Democrat in 1968 but was swamped by incumbent Jerry L. Bettis, R-Loma Linda, after a bitter fight, still has eyes for the House of Representatives.

"I've got to get $100,000 so that if reapportionment goes through, I can run. If I don't, the hell with it," he said.

If you ask Ballard if his six years in office changed him, he'll say, "People don't change. I learned a lot, but I knew more when I came in than any other mayor in the past twenty-five years. And I didn't have any records, any papers, to start off with."

For the immediate future, Ballard wants to develop two more mobile home parks. He already has one in San Bernardino and often spends weekends there, doing a lot of the work himself.

He said he's thinking of possible developments in Twentynine Palms and Ridgecrest.

Is there relief at leaving office?

"The one who'll appreciate it the most is my daughter. She is usually the one who answers the phone and you wouldn't believe what people have said to her. They're nice to me, but some people actually would cuss her out. This has been going on since she was about 11," said Ballard.

When he announced he wouldn't be seeking a new term, he expressed concern over the financial strain and personal hardships his terms in office had brought on him and his family.

When he leaves, Ballard will close an era that included:

-National publicity for his arming city fire trucks with shotguns and later encouraging citizens to arm themselves against rioters.

-Two County Grand Jury investigations dealing with finances. The 1966 jury said Ballard exceeded his authority and charged him with "willful misconduct" but evidence was insufficient for removal from office. The 1968 jury investigated an alleged $5,300 political contribution to Ballard from the Fire and Police Protective League. Evidence again wasn't sufficient to bring an indictment.

-Annexation of the National Orange Show grounds and Inland Shopping Center. The Orange Show measure cost the city $800,000 in Ballard-ordered improvements to provide a better "community image." And bitterness resulted when a promised regional sharing of the shopping center's sales tax proceeds didn't materialize.

-Public censure by two City Councils; one, for saying the only way to handle rioters is to shoot them, and once because he wrote a letter in behalf of Joseph C. Dippolito, identified by the Justice Department as being the one-time "underboss" of the Los Angeles Mafia.

-Removal of parking meters to fulfill one of Ballard's first campaign promises.

-A recall attempt led by some of his former supporters who charged him with improper financial dealings.

-Four city administrators in a four-year period, none of whom left smiling.

-Police being called on to enforce disobeyed demands that Councilman Michael R. Fagan attend a council meeting, that councilmen William Katona sit down and that City Attorney Ralph H. Prince keep his legal advice to himself. Ballard never ordered arrests.

-Annexation of almost seven square miles, including Patton State Hospital. San Bernardino was the first city in the state to use the new state Reorganization Act to annex sparsely populated areas without election.

-Use of the talents of Warner Hodgson to "light a fire" under dragging Central City Project so that the multimillion dollar redevelopment project could be speeded up. Hodgson, who fell out of favor with Ballard, was later convicted for failure to file personal income taxes.

-An aggressive seeking of federal aid that brought millions of dollars in the form of sewer and flood control drains, new buses, a reservoir, two community centers (one yet to be built), law enforcement studies and a share in the Central City Project and its six-story City Hall, cultural center, mall and public parking garage.

-On-again, off-again promises of a municipal airport and attendant industrial park, an 18-hole gold course and children's zoo.

-Two close shaves with personal injury for the mayor. One Halloween night the city helicopter bringing him home from a meeting with then Gov. Edmund G. (Pat) Brown crashed in Fontana. And two shots were fired at him and his city car was rammed when he tried to use it as a roadblock to help police during a racial disturbance.

-Warnings about using city money for such things as Christmas letters sent city wide and parties for visiting Mexican dignitaries.

-Ballard taking over as sewer plant superintendent after the former superintendent left amid controversy over why the plant stunk.

-"The Al Ballard Hour," a radio program the mayor seems to find a need for about every two years.

-Citizens' arrests by the mayor of panhandlers and speeders, a willingness to help stranded drivers and to pick up hitchhikers, an uncanny sense of timing that find him at the scenes of various crimes even before police arrived and a way of surprising citizens and employees alike by showing up unexpectedly at functions.

Among remembered bits of Ballard philosophy are these:

"A man that lies will steal."

"'Nice' guys don't win."

"I never read the paper."

"Coming close only counts in horseshoes."

"An expert is a guy from out of town with a briefcase."

"Never say, 'It can't be done,' but rather, 'How shall we do it'."

"The Grand Jury is up to its neck in partisan politics."

A rebel himself, Ballard abhors rebellious actions by the young. He insists on neat hair, no car and no rock concerts for his offspring as long as they're living with him. The Ballards have two daughters, Ann and Cheryl, and a son, James.

He favors stricter, not more lenient, marijuana penalties, more worrying about this nation and less about the rest of the world, and "extending" the law to wipe out juvenile delinquency.

When Assemblyman John P. Quimby, D-Rialto, encouraged Ballard to seek office six years ago, he referred to the mayor as a diamond in the rough.

While Ballard was able to polish up his approach, and, with help from his aides Winstead, H. R. Rainwater and Carlos P. Huesca, to present speeches they sometimes co-authored, the unBallard-like slickness of those addresses somehow diminished the colorful, bull-in-a-chinashop style that delighted many people.

He has a "street" sense, a former employe once said of Ballard. And, for all of his rebellious tactics, even the most conservative of his critics often conceded, "I'll give him credit for getting the job done."

Wonder what Thomas Jefferson might have thought about the Ballard mystique.

In 1787, Jefferson wrote a letter to James Madison saying, "I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical … It is a medicine necessary for the sound health of government."

The Sun (San Bernardino, CA.), P. 34, Col. 1

Fri., Aug. 5, 1994

Ballard

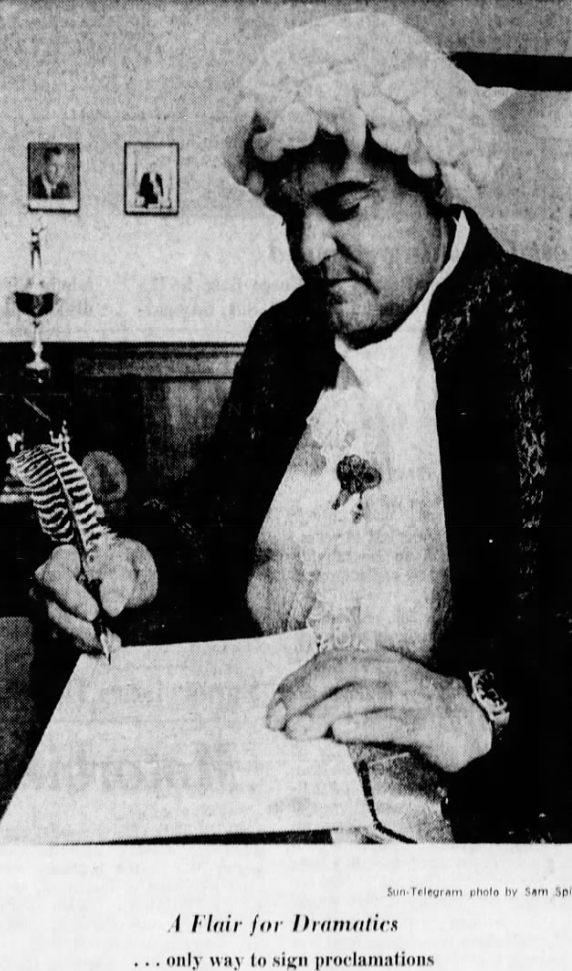

Al and Emma Ballard of San Bernardino celebrated their 50th anniversary July 28.

They were honored at a surprise informal reception in Claremont, hosted by their three children at the home of their daughter, Mrs. Cherly Winstead.

The couple were married July 28, 1944 in Seattle, Wash., and have lived in San Bernardino County for 49 years.

Their children are James Ballard of San Bernardino; Ann Ballard Fortuna of Orange and Cherly Ballard Winstead of Claremont.

The couple has four grandchildren.

Al Ballard was employed as a San Bernardino City Fireman from 1946 until he was elected mayor of San Bernardino in 1965, serving three terms. He has owned 23 different businesses in Southern California and remains active in the designing, construction and management of mobile home and recreational vehicle parks in Arizona, California and Nevada.

Emma Ballard is a homemaker and was office manager for the 23 businesses her husband owned and operated from 1946 to the present.

The couple has been honored by many organizations in San Bernardino County.

Al's parents were:

George Ballard, b. Jul. 1890 in Nelson County, KY. and d. Aug. 1973 in Louisville, Jefferson County, KY. &

Minnie J. Cummins, b. Nov. 1891 in Whitley County, KY. and d. Feb. 18, 1981 in Louisville, Jefferson County, KY.

The Sun-Telegram (San Bernardino, CA.), P. 1, Col. 4-6 and P. 19, Col. 1-6

Sun., May 2, 1971

Six Stormy Years in Office Reviewed

The Many Faces of Mayor Ballard

SAN BERNARDINO - We first met a couple of weeks after he was sworn into office for the first time. There had been a reorganization of news beats and I got City Hall.

"I'll never forget his first words to me: "I can't fight a girl."

Mayor Alvin Curtis Ballard, a farm boy from Kentucky, learns fast.

He soon became the fuel that made my typewriter go. He was nonstop hot copy.

A few years later, one of his aides chanced to be extolling his boss' virtues at a political luncheon and prophesied that people would still be talking about Al Ballard "50 years from now."

He said it as a matter of fact. Everyone who listened believed. They were learning to praise or to be confounded by the Ballard mystique. That's because the hard-driving ex-fireman who said he was "kidded into running" for the city's highest office, was well on his way to making a name for himself, not only in the city that he was commanding like the ringmaster for a one-man show, but across the country.

It's difficult to "live" with a mayor for six years and not learn to love him in a unique kind of way. In his dealings with the press, he likes to be close, but not too close; frank but not too frank.

A reporter-mayor relationship with Al Ballard can perhaps be summed up with the lines of a popular mouthwash commercial, "I hate it! But I love it!"

It didn't take long for reporters to realize that Ballard was probably way up there in the ratings against "Laugh-In" when City Council meetings and the TV show shared Monday night prime time.

Spectators sometimes filled the chamber. Reporters secretly wondered if he hadn't personally gone out to gather up all whom he could find. The larger audiences were usually pro-Ballard. They always cheered and booed in the appropriate places.

But those days came later. Early in his career, the regular 2 p.m. daily interviews were more like show-and-tell time in the big office at City Hall.

The mayor had been a city fireman for 18 1/2 years and before that was involved in a variety of businesses - 13 in all, he likes to tell people - before he was elected to his first term by outpolling incumbent Donald G. (Bud) Mauldin by 1,288 votes in 1965.

The newness of the office was apparent to Ballard in those early days. He would sometimes ask, "What do you think?" When asked how he was going to handle a problem. He really wanted to know.

He came to know many people and had many friends in many walks of life through his past occupations as a moonlighting weed abatement contractor, a plumber, a plasterer, service station owner and home builder.

But politics was a new field. Adaptable Al Ballard, who left the Catholic school he was attending in Louisville, Ky., to come to California when he was 17, learns fast.

The metamorphosis was rapid. Those daily meetings soon were no longer naive show-and-tell sessions. Ballard began keeping his guard up. He sometimes was defensive about some matters that, to the public, didn't appear to be in need of defense.

Maybe he learned to be that way because of his trips to Washington, D. C. It wasn't long after Ballard was in office that he learned there was "gold" on Capitol Hill and all he had to do was be there first with the best program and he could bring some home with him to San Bernardino.

Then he would sit at his desk with his constant cup of coffee looking like a cigar-loving Teddy bear while he told about "wining and dining" the people in Washington by night and proving to them he needed federal aid to keep his city on the move by day.

Sometimes Ballard throws words in terse, staccato sentences that land like body blows, these accompanied by fierce looks and a twist of the mouth.

He doesn't keep anything resembling "regular" hours now for talking to the press. That practice died quickly as the pace of the office grew.

More often than not, I found myself scrambling for a pencil when the Mayor suddenly burst into quotability while walking briskly down the street or when he impulsively picked up the car telephone and dialed my number.

This man of many moods changes them like a chameleon changes his colors. I soon learned not to be shocked when he whispered a confidence and then said with believability, "You print one word of that, and I'll kill you!"

Later he plants a gentle kiss on his 17-year-old daughter's cheek.

This is the coexistent tenderness and coarseness that make up the paradoxical Ballard Mystique.

A large man, Ballard stands 5 feet 11 and sometimes nears the 200 mark on the scales. Because of the constant rounds of dinner meetings and party invitations, his wife Emma must keep after him to watch his diet.

Both of them switched to high protein fare just before they visited Tachikawa, Japan, last year. Tachikawa is one of San Bernardino's sister cities.

Since he decided not to seek a fourth term in office, the mayor hasn't been watching the scales, however. In fact, he's taking on a new look. When he first came into office, he wore only dark blue suits, white shirts, conservative ties.

The new Ballard goes for mustard-colored dress shirts, five-inch wide ties with contrasting prints and, his latest addition, wire-frame, tinted, bifocal glasses.

Ballard leaves office on May 10, turning his gavel over to W. R. Holcomb, a wiry, blue-eyed lawyer who is a native of San Bernardino.

Straightening the spectacles and brushing back a shock of black, tousled hair, he grins, "I can wear anything I want now."

A thorn in the side to some; a benevolent friend to others. A "demonic slob" to one of his foes; the "person who was closest to me, next to my father," to J. T. Winstead, the city administrator Ballard hired as an aide when he was only 26 years old. Ballard truly will be remembered.

He said the other day that he is "worth $100,000 less than when I first came into office." This amount, amassed from his various businesses, which include the Fed discount service station and part ownership in a wed side medical building, he spent while in office.

"It's rough," he said. "In all these years, I've had to spend about $120 a day just in pocket money. For the first time since I've been in office, I've had to depend on my check (his mayor's salary of $600 per month)."

Ballard, who ran for Congress as a Democrat in 1968 but was swamped by incumbent Jerry L. Bettis, R-Loma Linda, after a bitter fight, still has eyes for the House of Representatives.

"I've got to get $100,000 so that if reapportionment goes through, I can run. If I don't, the hell with it," he said.

If you ask Ballard if his six years in office changed him, he'll say, "People don't change. I learned a lot, but I knew more when I came in than any other mayor in the past twenty-five years. And I didn't have any records, any papers, to start off with."

For the immediate future, Ballard wants to develop two more mobile home parks. He already has one in San Bernardino and often spends weekends there, doing a lot of the work himself.

He said he's thinking of possible developments in Twentynine Palms and Ridgecrest.

Is there relief at leaving office?

"The one who'll appreciate it the most is my daughter. She is usually the one who answers the phone and you wouldn't believe what people have said to her. They're nice to me, but some people actually would cuss her out. This has been going on since she was about 11," said Ballard.

When he announced he wouldn't be seeking a new term, he expressed concern over the financial strain and personal hardships his terms in office had brought on him and his family.

When he leaves, Ballard will close an era that included:

-National publicity for his arming city fire trucks with shotguns and later encouraging citizens to arm themselves against rioters.

-Two County Grand Jury investigations dealing with finances. The 1966 jury said Ballard exceeded his authority and charged him with "willful misconduct" but evidence was insufficient for removal from office. The 1968 jury investigated an alleged $5,300 political contribution to Ballard from the Fire and Police Protective League. Evidence again wasn't sufficient to bring an indictment.

-Annexation of the National Orange Show grounds and Inland Shopping Center. The Orange Show measure cost the city $800,000 in Ballard-ordered improvements to provide a better "community image." And bitterness resulted when a promised regional sharing of the shopping center's sales tax proceeds didn't materialize.

-Public censure by two City Councils; one, for saying the only way to handle rioters is to shoot them, and once because he wrote a letter in behalf of Joseph C. Dippolito, identified by the Justice Department as being the one-time "underboss" of the Los Angeles Mafia.

-Removal of parking meters to fulfill one of Ballard's first campaign promises.

-A recall attempt led by some of his former supporters who charged him with improper financial dealings.

-Four city administrators in a four-year period, none of whom left smiling.

-Police being called on to enforce disobeyed demands that Councilman Michael R. Fagan attend a council meeting, that councilmen William Katona sit down and that City Attorney Ralph H. Prince keep his legal advice to himself. Ballard never ordered arrests.

-Annexation of almost seven square miles, including Patton State Hospital. San Bernardino was the first city in the state to use the new state Reorganization Act to annex sparsely populated areas without election.

-Use of the talents of Warner Hodgson to "light a fire" under dragging Central City Project so that the multimillion dollar redevelopment project could be speeded up. Hodgson, who fell out of favor with Ballard, was later convicted for failure to file personal income taxes.

-An aggressive seeking of federal aid that brought millions of dollars in the form of sewer and flood control drains, new buses, a reservoir, two community centers (one yet to be built), law enforcement studies and a share in the Central City Project and its six-story City Hall, cultural center, mall and public parking garage.

-On-again, off-again promises of a municipal airport and attendant industrial park, an 18-hole gold course and children's zoo.

-Two close shaves with personal injury for the mayor. One Halloween night the city helicopter bringing him home from a meeting with then Gov. Edmund G. (Pat) Brown crashed in Fontana. And two shots were fired at him and his city car was rammed when he tried to use it as a roadblock to help police during a racial disturbance.

-Warnings about using city money for such things as Christmas letters sent city wide and parties for visiting Mexican dignitaries.

-Ballard taking over as sewer plant superintendent after the former superintendent left amid controversy over why the plant stunk.

-"The Al Ballard Hour," a radio program the mayor seems to find a need for about every two years.

-Citizens' arrests by the mayor of panhandlers and speeders, a willingness to help stranded drivers and to pick up hitchhikers, an uncanny sense of timing that find him at the scenes of various crimes even before police arrived and a way of surprising citizens and employees alike by showing up unexpectedly at functions.

Among remembered bits of Ballard philosophy are these:

"A man that lies will steal."

"'Nice' guys don't win."

"I never read the paper."

"Coming close only counts in horseshoes."

"An expert is a guy from out of town with a briefcase."

"Never say, 'It can't be done,' but rather, 'How shall we do it'."

"The Grand Jury is up to its neck in partisan politics."

A rebel himself, Ballard abhors rebellious actions by the young. He insists on neat hair, no car and no rock concerts for his offspring as long as they're living with him. The Ballards have two daughters, Ann and Cheryl, and a son, James.

He favors stricter, not more lenient, marijuana penalties, more worrying about this nation and less about the rest of the world, and "extending" the law to wipe out juvenile delinquency.

When Assemblyman John P. Quimby, D-Rialto, encouraged Ballard to seek office six years ago, he referred to the mayor as a diamond in the rough.

While Ballard was able to polish up his approach, and, with help from his aides Winstead, H. R. Rainwater and Carlos P. Huesca, to present speeches they sometimes co-authored, the unBallard-like slickness of those addresses somehow diminished the colorful, bull-in-a-chinashop style that delighted many people.

He has a "street" sense, a former employe once said of Ballard. And, for all of his rebellious tactics, even the most conservative of his critics often conceded, "I'll give him credit for getting the job done."

Wonder what Thomas Jefferson might have thought about the Ballard mystique.

In 1787, Jefferson wrote a letter to James Madison saying, "I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical … It is a medicine necessary for the sound health of government."

The Sun (San Bernardino, CA.), P. 34, Col. 1

Fri., Aug. 5, 1994

Ballard

Al and Emma Ballard of San Bernardino celebrated their 50th anniversary July 28.

They were honored at a surprise informal reception in Claremont, hosted by their three children at the home of their daughter, Mrs. Cherly Winstead.

The couple were married July 28, 1944 in Seattle, Wash., and have lived in San Bernardino County for 49 years.

Their children are James Ballard of San Bernardino; Ann Ballard Fortuna of Orange and Cherly Ballard Winstead of Claremont.

The couple has four grandchildren.

Al Ballard was employed as a San Bernardino City Fireman from 1946 until he was elected mayor of San Bernardino in 1965, serving three terms. He has owned 23 different businesses in Southern California and remains active in the designing, construction and management of mobile home and recreational vehicle parks in Arizona, California and Nevada.

Emma Ballard is a homemaker and was office manager for the 23 businesses her husband owned and operated from 1946 to the present.

The couple has been honored by many organizations in San Bernardino County.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement