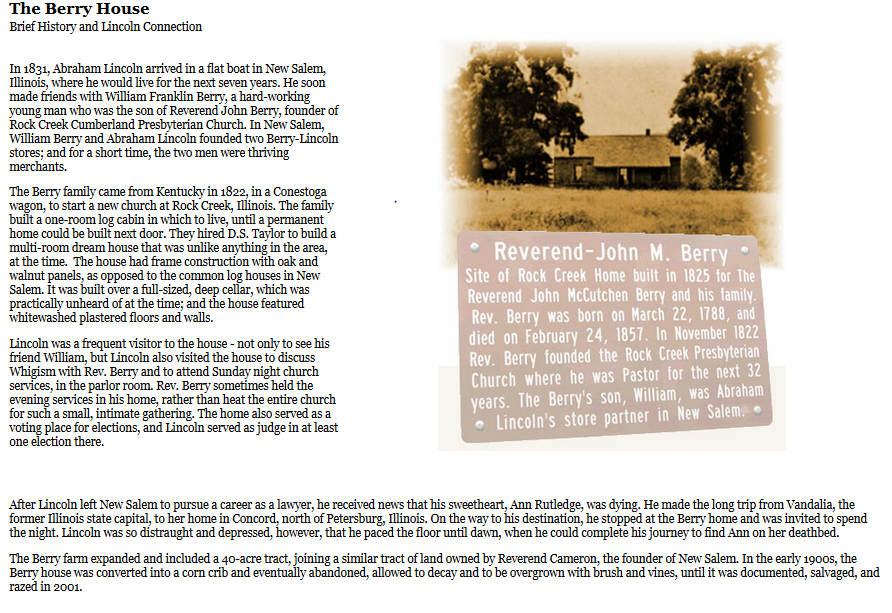

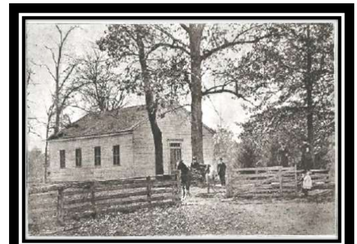

JOHN McCUTCHEN BERRY was born in the State of Virginia, on the 22d of March, 1788. Of his parentage and early education nothing in known. It is inferred, from some facts connected with his history, that his parents were religious persons, and perhaps stringent in some of their doctrinal views. His education, from the circumstances of his early life, must have been very limited. In his fourteenth year he came to Tennessee, and in his twentieth year professed religion, under the ministry of the fathers of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. His age at the time of his profession would bring that event within the days of the Council. They were days of trial.

He had a hard struggle, while under conviction, with difficulties arising from early doctrinal impressions. The doctrine of Election and Reprobation had been taught him in his youth. This is generally a trying puzzle in the early experience of persons who are seriously inquiring for the way of salvation. If tendencies have been originated in such minds towards the conclusions of the theology which has been mentioned, the difficulties become greater. This seems to have been the condition of young Berry. The guilt of sin pressed so severely upon him that he could not believe himself to be one of the elect; of course, his reasoning was, that he was proscribed by an unchangeable destiny; that no blood had been shed on Calvary for him; that his case was hopeless. A conflict of this kind is terrible.

"Such thoughts," says my authority, "drove him almost into despair. Of his deliverance he was accustomed to say, that on a certain day, giving the day itself, which we have forgotten, the sun arose at midnight."

The reader, of course, knows what he meant. His spiritual midnight had been changed to the light and beauty of the morning. It would be difficult to forget such an experience as this. I suppose he never forgot it. He retained, in all his subsequent life, a great aversion to the doctrine of a limited gospel provision. He thought that it had nearly ruined his soul. He did not preach often in direct opposition to the system, but salvation, full and free to all, was a favorite theme with him. It was a sort of a spiritual indoctrination.

Shortly after his conversion his mind began to be agitated on the subject of preaching the gospel. He, however, very naturally drew back from the undertaking. He was utterly unwilling to enter upon the work. His inward conflict was so great that he sometimes thought of resorting to suicide in order to quiet it. It is said that he actually went out one night with the intention of laying hands upon himself, but was mercifully restrained. In order to hedge up his own way he married early, and, as it turned out, either intentionally on his own part, or providentially on the part of God, who intended to scourge him with the greater severity into his duty, he had selected a wife who was as much opposed to his becoming a preacher as he was himself to preaching, Of course he had thrown very strong fetters around his feet. This hasty act gave him trouble, as we would have supposed. For many years after he entered the ministry his wife was impatient under the hardships the family had to suffer, and although he was a pure and faithful husband, yet, under a sense of duty, he often left his home, to be gone for weeks, with no prospect of earthly reward, bidding adieu for the time to his wife struggling against discontent with the lot which Providence had assigned her. Great must be the trial of a good man under such circumstances.

In 1812 he joined the army, in connection with a regiment commanded by Colonel Young Ewing, of Christian county, Kentucky. He seems to have moved to Kentucky. Says my authority:

"He has told me that during the campaign he was in a cold and backslidden state, living in the neglect of prayer, and indulging in much vain and idle conversation, but was unable to efface the impression against which he was striving."

The expedition in which the regiment was engaged in a great measure miscarried. It was sent against Indians around Fort Clark, in what is now the State of Illinois. They found no Indians, and, after a very near approach to starvation, returned. Rev. Finis Ewing was with the regiment of his brother, in the twofold capacity of a soldier and a chaplain.

In 1814, Mr. Berry entered the public service again, under the command of General Jackson, and was in the celebrated battle of the 8th of January, 1815, below New Orleans. Whilst the battle was raging, and the missiles of death were flying around him, perceiving himself to be in a very exposed situation, and that he might in a few moments be hurried into the presence of God, he threw his mind back upon his past life. His former rebellion and obstinacy came up in full view before him. He wept, prayed, and confessed his sins before God. He then and there promised that, if the Lord would spare his life, and restore to him the joys of salvation, and bring him again to his home, he would consent to preach, or to do, or to suffer whatever God, in his providence, might see fit to require at his hands. His prayer was answered. For the time, he was filled with unutterable joy. Says my informant:

"Often in his preaching have I heard him tell that he had enjoyed the love of God in his soul, at home and abroad, around the fireside, in the closet and in the grove, in the corn-field and amidst the storm of battle. I never dared, however, to ask him whether he continued to carry on the work of death with his fellow-soldiers after his renewed reconciliation with God. Still, no one who knew him will believe for a moment that a mean cowardice had anything to do with his surrender of himself to God that day."

In the fall of 1817, Mr. Berry was received under the care of the Logan Presbytery as a candidate for the ministry. Two years afterward, or in the fall of 1819, he was licensed to preach as a probationer. The sermons which he wrote in the course of his trials of two years' continuance, are said to have been unusually interesting and impressive. Sometimes the Presbytery and the congregations were moved to tears in hearing them read. Sometimes, whilst he was exercising his gifts publicly, he made it a matter of special prayer to God that, if he was really called to preach, as an evidence of it, a soul might be converted at his next appointment. We can easily see how an earnest and sincere man, without experience, might be led to desire such proofs of the genuineness of his calling, and how desirable they might be to all Christian ministers; still, they are not the proofs which God always gives, nor are they such as we have always a right to expect.

In 1820, Mr. Berry moved to Indiana, from Christian county, Kentucky, where he had been living for several years. The country in which he settled was new, the people were poor, farms had to be opened, and, as a matter of course, even where congregations were organized, they were not able to do much toward the support of a minister and his family. Some were, no doubt, unwilling to do what they were able. He tells, himself, of some members of the Church who refused to let him have what he needed for his family, for the evident reason that they were ashamed to sell, and too stingy to give, him what he needed. Others, less sensitive, sold to him, and charged him for what they sold more than they could get from common buyers. He was a preacher and needy, and they made his necessities their rule in selling. This was cruel treatment, but good men have received such treatment, both before and since. Some men of the world, however, took an interest in the welfare of our young preacher in the midst of his troubles, and rendered him timely assistance.

He was ordained in 1822, and shortly after his ordination moved to Illinois, and became one of the original members of the Illinois Presbytery, which was constituted in the fall of that year by the Cumberland Synod. From that time to 1829 there was but one Presbytery in the State of Illinois. In April of 1829, the Sangamon Presbytery held its first meeting. There were five ministers in this Presbytery in its organization, of whom Mr. Berry was one. He was, therefore, closely identified with the origin and early operations of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in that State. During the seven years in which there was but one Presbytery in the State, every one of its session, with a single exception, was held at a distance of from two to four days' travel on horseback from where he lived, and the sessions of the Synod were uniformly from three hundred to five hundred miles distant. Yet it was a matter of conscience with him to attend all the judicatures of the Church with which he was connected. Those old men have left us examples which ought to be a standing reproach to many of us. Think of a man's riding on horseback five hundred miles once every year to a meeting of Synod. Still, these long journeys were performed for conscience' sake. The first time the writer ever saw Mr. Berry was at a meeting of the Cumberland Synod in 1825, at a point which must have been three hundred miles from his home. It had never been, and was never afterward, held at a point nearer. It was generally one hundred or two hundred miles more remote. The rule was, and it was stringently urged in those days, that a plain providential hindrance, and nothing short of this, furnished a sufficient excuse for neglecting the judicatures of the Church.

After the settlement of Mr. Berry in Illinois, his life was spent very much as other ministers of his time and section of the Church spent their lives. Their labors were great, while their earthly remuneration was small. Whilst they dispensed the gospel to their fellow-men with great fidelity, they labored, like Paul and his fellow-laborers, with their own hands, and thus made themselves chargeable to no man. However we may reproach a congregation, or congregations, which permit such a condition of things, we admire the zeal and earnestness of the men who thus unselfishly devote themselves to the great work of saving souls. Men of such a spirit are those who have always kept, and will always keep, the Church alive.

In the winter of 1856 and 1857, Mr. Berry died, at his residence in Clinton, DeWitt county, Illinois. His last sermon was delivered at Sugar Creek, in Logan county, from the precious words of the Apostle: "And we know that all things work together for good to them that love God, to them who are the called according to his purpose." He had been assisting at a meeting at that place for several days, and was taken sick at the meeting, or shortly afterward, and died in a few days. He fell with his armor on. "Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord, from henceforth. Yea, saith the Spirit, that they may rest from their labors, and their works do follow them."

The subject of this sketch seems to have been what the world calls an original man, and all such men have distinctly marked traits of character Mr. Berry had his proportion of these. Some of them are brought out in the following letter from an intimate friend and fellow-laborer, written a few months after his death:

"OREGON, July 1, 1857.

"DEAR BROTHER:-I was in California, several hundred miles from home, when I first saw the account of Brother Berry's death. I could not restrain my tears, though I was in the house of a stranger. I directly sought the silent grove, where old associations rushed upon my mind, with many past scenes which can never return any more. I wept freely. But I asked myself, why should I weep? Could I have been so cruel and selfish as to retain him here any longer, had it been in my power, after he had labored so long and so faithfully, and done so much for his Master's cause? That he had his faults and frailties none will deny. But it is clear as noonday to my mind, that he had his sterling virtues, such as very few possess in the same degree. Among the natural gifts with which he was endowed, was a faculty of discerning or reading a man's character at first sight. We used to call this the gift of discerning spirits. You are aware that he and I were for many years confidential friends. And he never feared or hesitated to give me his opinion of any one. Sometimes I thought him mistaken; but, in every case, as far as I can now recollect, his judgment proved to be correct. He once pronounced a certain individual a snake in the grass. I thought him mistaken, but twenty years afterward, I found he was right, and I was wrong.

"There was a nobleness of soul after him that never would stoop to any thing mean or low, even if it might not be considered sinful. I always considered him one of the fairest Presbyters that I ever knew, or with whom I ever was associated. If I ever knew a man entirely clear of jealousy or envy, it was John M. Berry. You inquire about, and request me to send you, all his short, pithy sayings which I can remember. As to these, they were always so original, and seemed to be suggested so naturally in illustration of his subject, that it is not easy for me to call them up, only as I can call up the subjects that suggested them. They were very natural to him, and so abundant that, unlike any other person, he never used any one of them more than once. You probably recollect his rejoinder to the man who took him to task for his manner of expounding the Scriptures, because Brother Berry did not take every passage just as it was written, saying what it means, and meaning what it said. 'You take it that way, do you?' said Brother Berry. 'Yes,' said the man. 'Well, which, then, was Herod-a man or a fox?' referring him to the passage in Luke in which our Savior calls Herod 'that fox.' I was not sure, at first, that this was original, but I have never found it anywhere else.

"I will now relate an incident that took place at the first Presbytery I ever attended, which has had a great influence in shaping my course from that to the present time. The Illinois Presbytery then embraced the State. Brother Berry and Brother Joel Knight were the only ministers north of White county. A special session of Presbytery had been appointed in Sangamon county, for the purpose of ordaining Brother Thomas Campbell. Brother Berry was the only ordained minister who attended. At the regular session of Presbytery the inquiry came up, Was the special session of Presbytery held? It was answered in the negative. The members were individually called upon, and reasons for non-attendance were demanded of all the delinquents. Some pleaded want of a suitable horse to ride, others lack of money to bear their expenses, and others had feared that it might rain and raise the streams, and make muddy roads. The youngest member of Presbytery made light of the whole matter; stated that he had been South, married a wife, and therefore could not attend-in short, he made a joke of the whole affair. Brother Berry insisted, against all of them, that none had offered a providential reason. He urged, with all the ardor for which he was famous, the great importance of sustaining government, and the strong obligation that a minister of Jesus Christ should feel himself under to let nothing hinder him from attending the judicatures of the Church, which was not strictly providential. Several of the members were considered more talented than Brother Berry, and at first they were all against him. Presbytery finally pronounced the young brother who had married the wife guilty of unjustifiable delinquency, whilst the others barely escaped censure.

"In his remarks he said that no excuse should be offered to, or sustained by, Presbytery that we would not offer at the bar of God with a reasonable expectation that he would sustain it. I have tried to live up to the above rule ever since, and in every case it has governed my vote upon reasons offered by others for delinquency. Brother Berry remarked, in the debate, that he never knew a minister that was not regular in his attendance upon the judicatures of the Church who was useful to any great extent, and that such often hindered more than they helped. My observation proves the same to be true.

"Yours, as ever, NEILL JOHNSON."

We have additional characteristics and anecdotes of Mr. Berry.

He was accustomed to use great plainness of speech with candidates for the ministry. In some cases he drew upon himself lasting opposition. A particular class of young men could not bear his plainness with patience. By the same candor and frankness he made others his friends. He was always ready to help the humble and studious; he was ever ready to uphold the modest and unassuming. He could not tolerate lifeless preaching. On a certain occasion a young man, recently from a distant theological school, came to one of his meetings. He was, of course, invited to preach. He did so, but the sermon was dull. There were some withered flowers of rhetoric-some well-rounded periods, but they were too well-rounded; they had no point. When the sermon was closed, Mr. Berry whispered into the ear of him from whom I have an account of the occurrence, 'That was a pretty corpse." Still, he thought it was but a corpse, a body without a soul. He was accustomed to say, that every sermon ought to have so much of Christ in it, that any sinner in the congregation, if, in the providence of God, he should never hear another, might still know how to be saved.

He was punctual in the fulfillment of his appointments for preaching. In his early days Illinois was a rough country. The winters were terribly cold. One worthy preacher of another denomination was actually frozen to death. "In the spring," says my informant, "there were oceans of mud; the streams were poorly bridged, and many not bridged at all. In the summer, the horse-flies were so numerous and blood-thirsty that to travel even a few hours in the day was to risk the life of a horse. Preachers and other travelers were compelled to travel in the night, at the risk of their own lives and health; yet he attended his appointments, and preached Christ through all these difficulties." Half of the time of the ministers of those days, from June to November of each year, was spent in attending camp-meetings. Some inadequate idea can be formed of the labors, and hardships, and self-denial of these men; yet they were the men who laid, broad and deep, the foundations of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in Illinois. They labored, and other men are entering into their labors.

Mr. Berry was earnestly devoted to the temperance reformation. It seems that he found a powerful argument at home, in the aberrations of a wayward and perverse son. The evil course of the son was attributed by the father to the influence of a certain Church in the neighborhood, which opposed and ridiculed all the efforts of those who were trying to promote the cause of temperance. He had some success, however, in his work, as we shall see. Abraham Lincoln and Mr. Berry's prodigal son were at one time partners in a little store. It is not so said, but we should infer from the narrative that they probably sold whisky. Although Mr. Berry could not overcome the obstinacy of his son, he seems to have succeeded with the partner. On an occasion afterward, when Mr. Lincoln had risen to some eminence as a lawyer, a grog-shop in a particular neighborhood was exerting a bad influence upon some husbands. The wives of these men united their forces, assailed the establishment, knocked the heads out of the barrels, broke the bottles, and smashed up things generally. The women were prosecuted, and Mr. Lincoln volunteered his services in their defense. In the course of a powerful argument upon the evils of the use of, and of the traffic in, ardent spirits, whilst many in the crowded court-room were bathed in tears, the speaker turned, and pointing his bony finger toward Mr. Berry, who was standing near him, said, "There is the man who, years ago, was instrumental in convincing me of the evils of trafficking in, and using, ardent spirits; I am glad that I ever saw him; I am glad that I ever heard his testimony on this terrible subject." Tears ran down the venerable man's cheeks whilst he was thus brought so distinctly to the notice of the assembly. He was more honored that day than he would have been afterward had he been made Mr. Lincoln's Secretary of State.

Mr. Berry seems to have been deeply versed in a knowledge of human nature. We have a reference to this characteristic by our Oregon correspondent. It is said that he scarcely ever made a mistake in his estimate of the character of a man. An incident of this kind occurred at a certain time in the Presbytery to which he belonged. A young man came to one of their camp-meetings in a hunter's garb, and with a hunter's accouterments. He made a profession of religion before the meeting closed. This was all well enough. Hunters have, no doubt, often been converted. They are not worse than other men. After awhile he was an applicant to the Presbytery to be received as a candidate. Some of the good old people thought that his conversion was a sort of miracle-a partial parallel to the case of Saul of Tarsus. He was received, advanced, flattered. Mr. Berry, however, did not believe in him. He warned the Presbytery that if they advanced the young man they would regret it. Still, they persevered. The result was, he committed a flagrant wrong, and was deposed, and that was the end of his Cumberland Presbyterian history. We have had a number of such histories. The writer retraces more than one of them with sadness. We have sometimes succeeded, in our way, in making as far as men could make, very good preachers from very unpromising materials. Still, we have occasionally, in our attempts at miracles in this line, made miserable failures. We will learn, at last, that the general laws of Providence will not be contravened in our favor.

Every man who is a preacher, indeed, has something in his style and manner of preaching peculiar to himself. I present the following account of these, in the case of Mr. Berry, from the source from which I have chiefly derived my material for this sketch:

"Brother Berry," says my informant, "preached in a manner and style peculiar to himself. His discourses were made up of short, pithy sayings, which some of his friends called proverbs. Sometimes these would grow naturally out of his subject; at other times their connection with his subject was not so obvious. Sometimes he seemed to present a golden chain; at other times, a collection of golden links. He never said any thing which had no meaning; he was always easily understood, and when he became fully interested in a subject, critics who had a soul in them were obliged to forget their logic and their rhetoric. A whole congregation, at such times-the learned and unlearned, the old and young, all classes-would be borne away with a force nearly irresistible, whithersoever his powerful will chose to carry them. In the application of his sermons, he could contrast one thing with another with fewer words, and greater variety of them, than any man I ever knew. Heaven and its joys, contrasted with hell and its miseries; the death of a saint with the death of a sinner; life on earth with life in heaven, and life on earth with life in hell, were some of his terrible antitheses. On each successive occasion, too, on which he would use such a mode of presenting truth, he would use words and forms of expression which were wholly new, and still as forcible as others which were new when previously used. This characteristic of his sermons, whilst it rendered them exceedingly to the hearer at the time of delivery, was unfavorable to their recollection after the charm of the delivery had passed away."

Perhaps some allowance is to be made in reading this account, on the score of personal partiality; still, such preaching, if the reality approached what may seem to have had something of the ideal in it, must have been finely adapted to the earnest, practical sense of the hardy pioneers to whom it was addressed. And if such preaching is to be considered a specimen, it needs not surprise us to find new Synods and Presbyteries, and numerous congregations of earnest and devoted Cumberland Presbyterians in Illinois. Good seed was early sown.

An incident is mentioned, of a kind certainly to be deprecated, connected with an Illinois camp-meeting. It was characteristic of the times. I give it in the words of the narrator:

"The Eastern theological schools, in quite an early day, sent forth many of their students into Illinois, ordained as preachers; many of them filled with high notions of their own importance, and very contemptible notions of others. Some of these attended a Cumberland Presbyterian camp-meeting, and one of them, being invited to preach, undertook very unceremoniously to animadvert upon the doctrines which had been preached at the meeting, and the exercises and proceedings generally. It had been arranged that a young brother should follow with a sermon, but the programme was changed, and after a short intermission Brother Berry followed, and dealt as plainly with the stranger as he had dealt with the managers of the meeting. His objections were all met with a force and power which made him tremble like Felix or Belshazzar of old. Mr. Berry would up by referring to the spirit manifested by Christ whilst here on earth. 'I admit,' said he, 'that Christ was bold, but he was not impudent; he was humble, but not mean.' Then, pointing his finger toward the preacher, he said, 'Sir, you are both impudent and mean.'"

I have said that such incidents are to be deprecated. Sometimes, however, impertinent inexperience must receive instruction in a manner which is by no means agreeable to the instructor himself. Theological students, if they are taught nothing else, ought to be taught "how to behave themselves in the house of God."

I have a few personal recollections of Mr. Berry. I first met with him at the meeting of the Cumberland Synod in 1825; or, rather, I met with him on the way to the Synod. Some of his inquiries and conversations are not yet effaced from my mind. They were, however, not of a character to interest any one now. My next recollection of hi is connected with the General Assembly of 1845. Twenty years had elapsed. At the latter Assembly he was kind enough, as I thought, to manifest an interest in me which I had not expected. I was then connected with Cumberland College. He spoke of sending his son to the institution, expressing a hope that I might exert some good influence upon him. The young man, however, never came to the College.

In 1846, the Assembly met at Owensboro, in Kentucky. On his way thither he called at my house, and we went together to the meeting. On our way from Princeton, we spent a Sabbath in Madisonville, and he preached. It was a strong and well-expressed sermon. He was very companionable, and we had, of course, a great deal of conversation about men and things. He developed some of his idiosyncrasies. His judgments of some of our men were rather severe. It is certain that the men were not all perfect, and with regard to some of them he had made up his mind very distinctly. The parties have now, however, nearly all passed away. They understand each other, no doubt, better. They were all imperfect while here. We may allow, however, that they were equally honest; all meant well. He preached again at the Assembly, but I preached myself, at another house, at the same hour, and did not hear him. With that Assembly, and our return together to my house, our intercourse closed. His ability was very respectable, and his honesty in his opinions was, I suppose, unquestioned.

Mr. Berry published a sermon in the Theological Medium, of 1847, on the law and the gospel, or, man's fall and remedy; and another in the Medium of 1850, on the punishment of sin, and how to escape it. He also published, "Lectures on the Covenant and the Right to Church Membership," a volume of three hundred pages, which attracted some attention in their time. He was a good man, and Illinois, especially, ought to cherish his memory.

REV. JOHN M'CUTCHEN BERRY.

The subject of this sketch was born in Virginia, March 22, 1788. Of his parentage and early life but little is now known. His education was necessarily limited. He moved to Tennessee in his fourteenth year, and professed religion among the Cumberland Presbyterians in his twentieth year. His convictions were long and severe, at times bordering on despair. His mind was troubled with the old doctrine of election and reprobation taught in the Westminster Confession. He got to believe that he was eternally reprobated, and that therefore there was no mercy for him. The writer knows from experience something of the terrible anxieties this doctrine can produce when once it gets a lodgment in the mind (For what is here narrated we are mainly indebted to Rev. A. Johnson's letters as published in 1864 in the Western Cumberland Presbyterian, of which the writer was then Editor, and to Dr. Beard's "Second Series" of biographical sketches.) When at last the light broke into his soul, he described it as "the sun arising at midnight." Through all his ministerial course he had a great aversion, amounting almost to abhorrence of this terrible doctrine, that man's destiny is fixed from eternity, irrespective of any conditions.

Soon after his conversion he felt it to be his duty to preach the gospel, but strove against the impressions with great resolution. But the impressions followed him, and in order to get away from this duty, and the darkness of mind produced by his rebellion against God, he was greatly tempted to commit suicide, and at one time went out into the darkness to end his existence. Some influence, however, kept him from committing the deed. To drown these feelings he married, and married one who, like himself, was sternly opposed to his trying to be a preacher. He also joined the army in 1812 under Col. Young Ewing. The expedition was against the Indians in Illinois. The regiment marched to Fort Clark, found no Indians, and returned to Kentucky nearly starved for food. Col. Ewing was brother to Rev. Finis Ewing, one of the fathers of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. Finis Ewing was himself in the regiment as soldier and chaplain. Mr. Berry again entered the army, and was in the celebrated battle of New Orleans, fought on the 8th of January, 1815. It was in this battle, exposed to instant death, with men falling all around him, that Mr. Berry promised God, if spared to return home, he would serve him to the best of his ability in any position he called him. His soul at that time was filled with inexpressible delight and joy.

In 1817 Mr. Berry was received as a candidate under the care of Logan Presbytery. In the Fall of 1819 he was licensed to preach the gospel, and in 1822 he was ordained to the whole work of the gospel ministry. In 1820 he removed to the State of Indiana, where, like all other poor people, he labored on a farm to support his family and preached what he could. Shortly after his ordination he came to Illinois, and was one of the three members who formed the first Presbytery, as recorded elsewhere. He settled in Sangamon county (at that day but sparsely settled), and he was the only preacher of our people in all the northern part of the State. He continued a member of Illinois Presbytery until, in the Spring of 1829, Sangamon Presbytery held its first meeting, and he was one of its five ministers present. He lived and labored in this field for many years with wonderful success. In the latter part of his life he was a member, we think, of Mackinaw Presbytery, and remained so till his death, which occurred in the Winter of 1856 and 1857, at his residence in Clinton, DeWitt county. His last sermon was delivered at old Sugar Creek, in Logan county, some ten miles north of Lincoln, from Rom viii. 28. He died as he had lived: with his armor on, and in the field of battle.

Mr. Berry was a very positive man. His opinions were very decided, and his preaching was bold, frank, unvarnished. The writer first met him in the town of Greenfield, at the session of Sangamon Presbytery in 1854, only a little over two years before his death. He was very impressive as a speaker. His points were made clear and strong, and he was a man of large influence over the entire State. We had the impression that no man of his day, if we may except Rev. Mr. McLin, had as much to do in forming the character and establishing the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in Illinois as had Mr. Berry.

In the latter part of his life he entertained extreme views on the subject of baptism, which crippled his influence with a portion of the Church. In his early ministry he was in the habit of baptizing often by immersion, if the subject preferred this mode. This, indeed, was the common practice thirty years ago. Mr. Berry had a case of this kind. It was a lady. The season was dry and sufficient water was hard to procure. The baptism was delayed some hours, certain parties having to dam up a little stream so as to accumulate water enough to immerse the body. Mr. Berry felt that he and the entire audience were placed under very embarrassing circumstances. It led him to a careful examination of the subject as to whether God required a mode which, many times, places the subject and administrator under embarrassments like those under which they were laboring. His mind underwent a great revolution on this question, and he came to the firm conviction that immersion is not baptism at all; that all who are immersed are yet unbaptized, and consequently are not in the Church at all--baptism, as he viewed it, being the door into the visible Church. Mr. Berry was not a man to believe strongly in the necessity and importance of a dogma, and not preach it. Accordingly, he preached and argued his new doctrine far and near, producing at the time quite a sensation among the churches of his Presbytery and Synod. So far did he carry his view that he refused to administer the sacrament of the Supper to those who had been immersed, alleging that they were unbaptized, and therefore had no right to partake of the Lord's Supper. About this time he published his book entitle, "The Covenants," in which the doctrine just mentioned is strongly urged. Before the close of his life he seemed to lose sight, somewhat, of this theme, and go back to the themes of his younger days in the ministry; and the excitement over his theory had well nigh died out.

Mr. Berry was very prompt in his attendance upon the judicatories of the Church. He was never absent unless positively hindered by sickness or death, often riding from one hundred to five hundred miles to get there, and that, too, over swollen streams and through mud and almost boundless prairies, many times without any road as a guide to the place of destination. He was a man of great courage and perseverance, of unquestioned integrity, and of spotless character. There was one thing which seemed to trouble him more than all else, and that was a son, who became dissipated. Mr. Berry was much from home, and it appears that while not under the immediate eye of his father, the son acquired a taste for strong drink. This, with its attendant evils, gave the parents much anxiety, and even anguish of mind. Dr. Beard relates an incident connected with this son's case, which we think worthy of repeating here. We may here state, that no man could have been more opposed to intemperance, or a stronger advocate of total abstinence from all intoxicating drinks as a beverage, than was Mr. Berry. His was an uncompromising war upon the enemy at all times. But to the incident: "Abraham Lincoln and Mr. Berry's prodigal son were at one time partners in a little store. It is not so stated, but we should infer from the narrative that they probably sold whisky. Although Mr. Berry could not overcome the obstinacy of his son, he seems to have succeeded with the partner. On one occasion afterward, when Mr. Lincoln had risen to some eminence as a lawyer, a grog shop in a particular neighborhood was exerting a bad influence upon some husbands. The wives of these men united their forces, assailed the establishment, knocked the heads out of the barrels, broke the bottles, and smashed up things generally. The women were prosecuted, and Mr. Lincoln volunteered his services in their defense. In the course of a powerful argument upon the evils of the use of, and of the traffic in, ardent spirits, whilst many in the crowded court room were bathed in tears, the speaker turned, and, pointing his bony finger towards Mr. Berry, who was standing near him, said: 'There is the man who, years ago, was instrumental in convincing me of the evils of trafficing in the using ardent spirits. I am glad that I ever saw him. I am glad that I ever heard his testimony on this terrible subject.'" Several years ago, while traveling in that part of the State in company with another minister, he pointed out to the writer the spot by the roadside where stood the little store referred to by Dr. Beard. Mr. Lincoln is not the only great man in political circles who has received some good influences from the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. Dr. Beard concludes this incident by saying, that Mr. Berry "was more honored that day than he would have been afterwards had he been made Mr. Lincoln's Secretary of State." And so he was.

We did not meet with Mr. Berry but two or three times prior to his death. The last time we saw him was at the meeting of Sangamon Synod the year before his death. he preached on the occasion a good, strong sermon, attended with warmth and energy. The impression made upon the mind of the writer was, that Mr. Berry was a plain, pointed, gospel preacher, seeking no display, desiring no applause from men. And when he was fully enlisted in his subject, he was powerful, and sometimes almost irresistible. He did a great and glorious work, and has gone to his rest and reward.

The Rev. John M. Berry

1788-1856

The Rev. John M'Cutchen Berry is a minister of special interest to this community, not only because he was here to help organize the first presbytery, but because he was related to the Johnsons, who have had members in this church since the beginning in 1819. The Rev. Berry before his conversion was in the War of 1812. The bullets were flying all around him in battle, and he promised the Lord that if He spared his life, he would preach the Gospel, a duty he had tried to escape. He was ordained in 1822, and soon came to Illinois. He was a very positive man, and his preaching was bold, frank, and unvarnished, making him a very impressive speaker. His points were made clear and strong, and he had much influence, over the entire state. He, like the Rev. McLin, did much in forming the character and establishing the Cumberland Presbyterian church in Illinois. His death occurred at Clinton, Illinois.

JOHN McCUTCHEN BERRY was born in the State of Virginia, on the 22d of March, 1788. Of his parentage and early education nothing in known. It is inferred, from some facts connected with his history, that his parents were religious persons, and perhaps stringent in some of their doctrinal views. His education, from the circumstances of his early life, must have been very limited. In his fourteenth year he came to Tennessee, and in his twentieth year professed religion, under the ministry of the fathers of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. His age at the time of his profession would bring that event within the days of the Council. They were days of trial.

He had a hard struggle, while under conviction, with difficulties arising from early doctrinal impressions. The doctrine of Election and Reprobation had been taught him in his youth. This is generally a trying puzzle in the early experience of persons who are seriously inquiring for the way of salvation. If tendencies have been originated in such minds towards the conclusions of the theology which has been mentioned, the difficulties become greater. This seems to have been the condition of young Berry. The guilt of sin pressed so severely upon him that he could not believe himself to be one of the elect; of course, his reasoning was, that he was proscribed by an unchangeable destiny; that no blood had been shed on Calvary for him; that his case was hopeless. A conflict of this kind is terrible.

"Such thoughts," says my authority, "drove him almost into despair. Of his deliverance he was accustomed to say, that on a certain day, giving the day itself, which we have forgotten, the sun arose at midnight."

The reader, of course, knows what he meant. His spiritual midnight had been changed to the light and beauty of the morning. It would be difficult to forget such an experience as this. I suppose he never forgot it. He retained, in all his subsequent life, a great aversion to the doctrine of a limited gospel provision. He thought that it had nearly ruined his soul. He did not preach often in direct opposition to the system, but salvation, full and free to all, was a favorite theme with him. It was a sort of a spiritual indoctrination.

Shortly after his conversion his mind began to be agitated on the subject of preaching the gospel. He, however, very naturally drew back from the undertaking. He was utterly unwilling to enter upon the work. His inward conflict was so great that he sometimes thought of resorting to suicide in order to quiet it. It is said that he actually went out one night with the intention of laying hands upon himself, but was mercifully restrained. In order to hedge up his own way he married early, and, as it turned out, either intentionally on his own part, or providentially on the part of God, who intended to scourge him with the greater severity into his duty, he had selected a wife who was as much opposed to his becoming a preacher as he was himself to preaching, Of course he had thrown very strong fetters around his feet. This hasty act gave him trouble, as we would have supposed. For many years after he entered the ministry his wife was impatient under the hardships the family had to suffer, and although he was a pure and faithful husband, yet, under a sense of duty, he often left his home, to be gone for weeks, with no prospect of earthly reward, bidding adieu for the time to his wife struggling against discontent with the lot which Providence had assigned her. Great must be the trial of a good man under such circumstances.

In 1812 he joined the army, in connection with a regiment commanded by Colonel Young Ewing, of Christian county, Kentucky. He seems to have moved to Kentucky. Says my authority:

"He has told me that during the campaign he was in a cold and backslidden state, living in the neglect of prayer, and indulging in much vain and idle conversation, but was unable to efface the impression against which he was striving."

The expedition in which the regiment was engaged in a great measure miscarried. It was sent against Indians around Fort Clark, in what is now the State of Illinois. They found no Indians, and, after a very near approach to starvation, returned. Rev. Finis Ewing was with the regiment of his brother, in the twofold capacity of a soldier and a chaplain.

In 1814, Mr. Berry entered the public service again, under the command of General Jackson, and was in the celebrated battle of the 8th of January, 1815, below New Orleans. Whilst the battle was raging, and the missiles of death were flying around him, perceiving himself to be in a very exposed situation, and that he might in a few moments be hurried into the presence of God, he threw his mind back upon his past life. His former rebellion and obstinacy came up in full view before him. He wept, prayed, and confessed his sins before God. He then and there promised that, if the Lord would spare his life, and restore to him the joys of salvation, and bring him again to his home, he would consent to preach, or to do, or to suffer whatever God, in his providence, might see fit to require at his hands. His prayer was answered. For the time, he was filled with unutterable joy. Says my informant:

"Often in his preaching have I heard him tell that he had enjoyed the love of God in his soul, at home and abroad, around the fireside, in the closet and in the grove, in the corn-field and amidst the storm of battle. I never dared, however, to ask him whether he continued to carry on the work of death with his fellow-soldiers after his renewed reconciliation with God. Still, no one who knew him will believe for a moment that a mean cowardice had anything to do with his surrender of himself to God that day."

In the fall of 1817, Mr. Berry was received under the care of the Logan Presbytery as a candidate for the ministry. Two years afterward, or in the fall of 1819, he was licensed to preach as a probationer. The sermons which he wrote in the course of his trials of two years' continuance, are said to have been unusually interesting and impressive. Sometimes the Presbytery and the congregations were moved to tears in hearing them read. Sometimes, whilst he was exercising his gifts publicly, he made it a matter of special prayer to God that, if he was really called to preach, as an evidence of it, a soul might be converted at his next appointment. We can easily see how an earnest and sincere man, without experience, might be led to desire such proofs of the genuineness of his calling, and how desirable they might be to all Christian ministers; still, they are not the proofs which God always gives, nor are they such as we have always a right to expect.

In 1820, Mr. Berry moved to Indiana, from Christian county, Kentucky, where he had been living for several years. The country in which he settled was new, the people were poor, farms had to be opened, and, as a matter of course, even where congregations were organized, they were not able to do much toward the support of a minister and his family. Some were, no doubt, unwilling to do what they were able. He tells, himself, of some members of the Church who refused to let him have what he needed for his family, for the evident reason that they were ashamed to sell, and too stingy to give, him what he needed. Others, less sensitive, sold to him, and charged him for what they sold more than they could get from common buyers. He was a preacher and needy, and they made his necessities their rule in selling. This was cruel treatment, but good men have received such treatment, both before and since. Some men of the world, however, took an interest in the welfare of our young preacher in the midst of his troubles, and rendered him timely assistance.

He was ordained in 1822, and shortly after his ordination moved to Illinois, and became one of the original members of the Illinois Presbytery, which was constituted in the fall of that year by the Cumberland Synod. From that time to 1829 there was but one Presbytery in the State of Illinois. In April of 1829, the Sangamon Presbytery held its first meeting. There were five ministers in this Presbytery in its organization, of whom Mr. Berry was one. He was, therefore, closely identified with the origin and early operations of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in that State. During the seven years in which there was but one Presbytery in the State, every one of its session, with a single exception, was held at a distance of from two to four days' travel on horseback from where he lived, and the sessions of the Synod were uniformly from three hundred to five hundred miles distant. Yet it was a matter of conscience with him to attend all the judicatures of the Church with which he was connected. Those old men have left us examples which ought to be a standing reproach to many of us. Think of a man's riding on horseback five hundred miles once every year to a meeting of Synod. Still, these long journeys were performed for conscience' sake. The first time the writer ever saw Mr. Berry was at a meeting of the Cumberland Synod in 1825, at a point which must have been three hundred miles from his home. It had never been, and was never afterward, held at a point nearer. It was generally one hundred or two hundred miles more remote. The rule was, and it was stringently urged in those days, that a plain providential hindrance, and nothing short of this, furnished a sufficient excuse for neglecting the judicatures of the Church.

After the settlement of Mr. Berry in Illinois, his life was spent very much as other ministers of his time and section of the Church spent their lives. Their labors were great, while their earthly remuneration was small. Whilst they dispensed the gospel to their fellow-men with great fidelity, they labored, like Paul and his fellow-laborers, with their own hands, and thus made themselves chargeable to no man. However we may reproach a congregation, or congregations, which permit such a condition of things, we admire the zeal and earnestness of the men who thus unselfishly devote themselves to the great work of saving souls. Men of such a spirit are those who have always kept, and will always keep, the Church alive.

In the winter of 1856 and 1857, Mr. Berry died, at his residence in Clinton, DeWitt county, Illinois. His last sermon was delivered at Sugar Creek, in Logan county, from the precious words of the Apostle: "And we know that all things work together for good to them that love God, to them who are the called according to his purpose." He had been assisting at a meeting at that place for several days, and was taken sick at the meeting, or shortly afterward, and died in a few days. He fell with his armor on. "Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord, from henceforth. Yea, saith the Spirit, that they may rest from their labors, and their works do follow them."

The subject of this sketch seems to have been what the world calls an original man, and all such men have distinctly marked traits of character Mr. Berry had his proportion of these. Some of them are brought out in the following letter from an intimate friend and fellow-laborer, written a few months after his death:

"OREGON, July 1, 1857.

"DEAR BROTHER:-I was in California, several hundred miles from home, when I first saw the account of Brother Berry's death. I could not restrain my tears, though I was in the house of a stranger. I directly sought the silent grove, where old associations rushed upon my mind, with many past scenes which can never return any more. I wept freely. But I asked myself, why should I weep? Could I have been so cruel and selfish as to retain him here any longer, had it been in my power, after he had labored so long and so faithfully, and done so much for his Master's cause? That he had his faults and frailties none will deny. But it is clear as noonday to my mind, that he had his sterling virtues, such as very few possess in the same degree. Among the natural gifts with which he was endowed, was a faculty of discerning or reading a man's character at first sight. We used to call this the gift of discerning spirits. You are aware that he and I were for many years confidential friends. And he never feared or hesitated to give me his opinion of any one. Sometimes I thought him mistaken; but, in every case, as far as I can now recollect, his judgment proved to be correct. He once pronounced a certain individual a snake in the grass. I thought him mistaken, but twenty years afterward, I found he was right, and I was wrong.

"There was a nobleness of soul after him that never would stoop to any thing mean or low, even if it might not be considered sinful. I always considered him one of the fairest Presbyters that I ever knew, or with whom I ever was associated. If I ever knew a man entirely clear of jealousy or envy, it was John M. Berry. You inquire about, and request me to send you, all his short, pithy sayings which I can remember. As to these, they were always so original, and seemed to be suggested so naturally in illustration of his subject, that it is not easy for me to call them up, only as I can call up the subjects that suggested them. They were very natural to him, and so abundant that, unlike any other person, he never used any one of them more than once. You probably recollect his rejoinder to the man who took him to task for his manner of expounding the Scriptures, because Brother Berry did not take every passage just as it was written, saying what it means, and meaning what it said. 'You take it that way, do you?' said Brother Berry. 'Yes,' said the man. 'Well, which, then, was Herod-a man or a fox?' referring him to the passage in Luke in which our Savior calls Herod 'that fox.' I was not sure, at first, that this was original, but I have never found it anywhere else.

"I will now relate an incident that took place at the first Presbytery I ever attended, which has had a great influence in shaping my course from that to the present time. The Illinois Presbytery then embraced the State. Brother Berry and Brother Joel Knight were the only ministers north of White county. A special session of Presbytery had been appointed in Sangamon county, for the purpose of ordaining Brother Thomas Campbell. Brother Berry was the only ordained minister who attended. At the regular session of Presbytery the inquiry came up, Was the special session of Presbytery held? It was answered in the negative. The members were individually called upon, and reasons for non-attendance were demanded of all the delinquents. Some pleaded want of a suitable horse to ride, others lack of money to bear their expenses, and others had feared that it might rain and raise the streams, and make muddy roads. The youngest member of Presbytery made light of the whole matter; stated that he had been South, married a wife, and therefore could not attend-in short, he made a joke of the whole affair. Brother Berry insisted, against all of them, that none had offered a providential reason. He urged, with all the ardor for which he was famous, the great importance of sustaining government, and the strong obligation that a minister of Jesus Christ should feel himself under to let nothing hinder him from attending the judicatures of the Church, which was not strictly providential. Several of the members were considered more talented than Brother Berry, and at first they were all against him. Presbytery finally pronounced the young brother who had married the wife guilty of unjustifiable delinquency, whilst the others barely escaped censure.

"In his remarks he said that no excuse should be offered to, or sustained by, Presbytery that we would not offer at the bar of God with a reasonable expectation that he would sustain it. I have tried to live up to the above rule ever since, and in every case it has governed my vote upon reasons offered by others for delinquency. Brother Berry remarked, in the debate, that he never knew a minister that was not regular in his attendance upon the judicatures of the Church who was useful to any great extent, and that such often hindered more than they helped. My observation proves the same to be true.

"Yours, as ever, NEILL JOHNSON."

We have additional characteristics and anecdotes of Mr. Berry.

He was accustomed to use great plainness of speech with candidates for the ministry. In some cases he drew upon himself lasting opposition. A particular class of young men could not bear his plainness with patience. By the same candor and frankness he made others his friends. He was always ready to help the humble and studious; he was ever ready to uphold the modest and unassuming. He could not tolerate lifeless preaching. On a certain occasion a young man, recently from a distant theological school, came to one of his meetings. He was, of course, invited to preach. He did so, but the sermon was dull. There were some withered flowers of rhetoric-some well-rounded periods, but they were too well-rounded; they had no point. When the sermon was closed, Mr. Berry whispered into the ear of him from whom I have an account of the occurrence, 'That was a pretty corpse." Still, he thought it was but a corpse, a body without a soul. He was accustomed to say, that every sermon ought to have so much of Christ in it, that any sinner in the congregation, if, in the providence of God, he should never hear another, might still know how to be saved.

He was punctual in the fulfillment of his appointments for preaching. In his early days Illinois was a rough country. The winters were terribly cold. One worthy preacher of another denomination was actually frozen to death. "In the spring," says my informant, "there were oceans of mud; the streams were poorly bridged, and many not bridged at all. In the summer, the horse-flies were so numerous and blood-thirsty that to travel even a few hours in the day was to risk the life of a horse. Preachers and other travelers were compelled to travel in the night, at the risk of their own lives and health; yet he attended his appointments, and preached Christ through all these difficulties." Half of the time of the ministers of those days, from June to November of each year, was spent in attending camp-meetings. Some inadequate idea can be formed of the labors, and hardships, and self-denial of these men; yet they were the men who laid, broad and deep, the foundations of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in Illinois. They labored, and other men are entering into their labors.

Mr. Berry was earnestly devoted to the temperance reformation. It seems that he found a powerful argument at home, in the aberrations of a wayward and perverse son. The evil course of the son was attributed by the father to the influence of a certain Church in the neighborhood, which opposed and ridiculed all the efforts of those who were trying to promote the cause of temperance. He had some success, however, in his work, as we shall see. Abraham Lincoln and Mr. Berry's prodigal son were at one time partners in a little store. It is not so said, but we should infer from the narrative that they probably sold whisky. Although Mr. Berry could not overcome the obstinacy of his son, he seems to have succeeded with the partner. On an occasion afterward, when Mr. Lincoln had risen to some eminence as a lawyer, a grog-shop in a particular neighborhood was exerting a bad influence upon some husbands. The wives of these men united their forces, assailed the establishment, knocked the heads out of the barrels, broke the bottles, and smashed up things generally. The women were prosecuted, and Mr. Lincoln volunteered his services in their defense. In the course of a powerful argument upon the evils of the use of, and of the traffic in, ardent spirits, whilst many in the crowded court-room were bathed in tears, the speaker turned, and pointing his bony finger toward Mr. Berry, who was standing near him, said, "There is the man who, years ago, was instrumental in convincing me of the evils of trafficking in, and using, ardent spirits; I am glad that I ever saw him; I am glad that I ever heard his testimony on this terrible subject." Tears ran down the venerable man's cheeks whilst he was thus brought so distinctly to the notice of the assembly. He was more honored that day than he would have been afterward had he been made Mr. Lincoln's Secretary of State.

Mr. Berry seems to have been deeply versed in a knowledge of human nature. We have a reference to this characteristic by our Oregon correspondent. It is said that he scarcely ever made a mistake in his estimate of the character of a man. An incident of this kind occurred at a certain time in the Presbytery to which he belonged. A young man came to one of their camp-meetings in a hunter's garb, and with a hunter's accouterments. He made a profession of religion before the meeting closed. This was all well enough. Hunters have, no doubt, often been converted. They are not worse than other men. After awhile he was an applicant to the Presbytery to be received as a candidate. Some of the good old people thought that his conversion was a sort of miracle-a partial parallel to the case of Saul of Tarsus. He was received, advanced, flattered. Mr. Berry, however, did not believe in him. He warned the Presbytery that if they advanced the young man they would regret it. Still, they persevered. The result was, he committed a flagrant wrong, and was deposed, and that was the end of his Cumberland Presbyterian history. We have had a number of such histories. The writer retraces more than one of them with sadness. We have sometimes succeeded, in our way, in making as far as men could make, very good preachers from very unpromising materials. Still, we have occasionally, in our attempts at miracles in this line, made miserable failures. We will learn, at last, that the general laws of Providence will not be contravened in our favor.

Every man who is a preacher, indeed, has something in his style and manner of preaching peculiar to himself. I present the following account of these, in the case of Mr. Berry, from the source from which I have chiefly derived my material for this sketch:

"Brother Berry," says my informant, "preached in a manner and style peculiar to himself. His discourses were made up of short, pithy sayings, which some of his friends called proverbs. Sometimes these would grow naturally out of his subject; at other times their connection with his subject was not so obvious. Sometimes he seemed to present a golden chain; at other times, a collection of golden links. He never said any thing which had no meaning; he was always easily understood, and when he became fully interested in a subject, critics who had a soul in them were obliged to forget their logic and their rhetoric. A whole congregation, at such times-the learned and unlearned, the old and young, all classes-would be borne away with a force nearly irresistible, whithersoever his powerful will chose to carry them. In the application of his sermons, he could contrast one thing with another with fewer words, and greater variety of them, than any man I ever knew. Heaven and its joys, contrasted with hell and its miseries; the death of a saint with the death of a sinner; life on earth with life in heaven, and life on earth with life in hell, were some of his terrible antitheses. On each successive occasion, too, on which he would use such a mode of presenting truth, he would use words and forms of expression which were wholly new, and still as forcible as others which were new when previously used. This characteristic of his sermons, whilst it rendered them exceedingly to the hearer at the time of delivery, was unfavorable to their recollection after the charm of the delivery had passed away."

Perhaps some allowance is to be made in reading this account, on the score of personal partiality; still, such preaching, if the reality approached what may seem to have had something of the ideal in it, must have been finely adapted to the earnest, practical sense of the hardy pioneers to whom it was addressed. And if such preaching is to be considered a specimen, it needs not surprise us to find new Synods and Presbyteries, and numerous congregations of earnest and devoted Cumberland Presbyterians in Illinois. Good seed was early sown.

An incident is mentioned, of a kind certainly to be deprecated, connected with an Illinois camp-meeting. It was characteristic of the times. I give it in the words of the narrator:

"The Eastern theological schools, in quite an early day, sent forth many of their students into Illinois, ordained as preachers; many of them filled with high notions of their own importance, and very contemptible notions of others. Some of these attended a Cumberland Presbyterian camp-meeting, and one of them, being invited to preach, undertook very unceremoniously to animadvert upon the doctrines which had been preached at the meeting, and the exercises and proceedings generally. It had been arranged that a young brother should follow with a sermon, but the programme was changed, and after a short intermission Brother Berry followed, and dealt as plainly with the stranger as he had dealt with the managers of the meeting. His objections were all met with a force and power which made him tremble like Felix or Belshazzar of old. Mr. Berry would up by referring to the spirit manifested by Christ whilst here on earth. 'I admit,' said he, 'that Christ was bold, but he was not impudent; he was humble, but not mean.' Then, pointing his finger toward the preacher, he said, 'Sir, you are both impudent and mean.'"

I have said that such incidents are to be deprecated. Sometimes, however, impertinent inexperience must receive instruction in a manner which is by no means agreeable to the instructor himself. Theological students, if they are taught nothing else, ought to be taught "how to behave themselves in the house of God."

I have a few personal recollections of Mr. Berry. I first met with him at the meeting of the Cumberland Synod in 1825; or, rather, I met with him on the way to the Synod. Some of his inquiries and conversations are not yet effaced from my mind. They were, however, not of a character to interest any one now. My next recollection of hi is connected with the General Assembly of 1845. Twenty years had elapsed. At the latter Assembly he was kind enough, as I thought, to manifest an interest in me which I had not expected. I was then connected with Cumberland College. He spoke of sending his son to the institution, expressing a hope that I might exert some good influence upon him. The young man, however, never came to the College.

In 1846, the Assembly met at Owensboro, in Kentucky. On his way thither he called at my house, and we went together to the meeting. On our way from Princeton, we spent a Sabbath in Madisonville, and he preached. It was a strong and well-expressed sermon. He was very companionable, and we had, of course, a great deal of conversation about men and things. He developed some of his idiosyncrasies. His judgments of some of our men were rather severe. It is certain that the men were not all perfect, and with regard to some of them he had made up his mind very distinctly. The parties have now, however, nearly all passed away. They understand each other, no doubt, better. They were all imperfect while here. We may allow, however, that they were equally honest; all meant well. He preached again at the Assembly, but I preached myself, at another house, at the same hour, and did not hear him. With that Assembly, and our return together to my house, our intercourse closed. His ability was very respectable, and his honesty in his opinions was, I suppose, unquestioned.

Mr. Berry published a sermon in the Theological Medium, of 1847, on the law and the gospel, or, man's fall and remedy; and another in the Medium of 1850, on the punishment of sin, and how to escape it. He also published, "Lectures on the Covenant and the Right to Church Membership," a volume of three hundred pages, which attracted some attention in their time. He was a good man, and Illinois, especially, ought to cherish his memory.

REV. JOHN M'CUTCHEN BERRY.

The subject of this sketch was born in Virginia, March 22, 1788. Of his parentage and early life but little is now known. His education was necessarily limited. He moved to Tennessee in his fourteenth year, and professed religion among the Cumberland Presbyterians in his twentieth year. His convictions were long and severe, at times bordering on despair. His mind was troubled with the old doctrine of election and reprobation taught in the Westminster Confession. He got to believe that he was eternally reprobated, and that therefore there was no mercy for him. The writer knows from experience something of the terrible anxieties this doctrine can produce when once it gets a lodgment in the mind (For what is here narrated we are mainly indebted to Rev. A. Johnson's letters as published in 1864 in the Western Cumberland Presbyterian, of which the writer was then Editor, and to Dr. Beard's "Second Series" of biographical sketches.) When at last the light broke into his soul, he described it as "the sun arising at midnight." Through all his ministerial course he had a great aversion, amounting almost to abhorrence of this terrible doctrine, that man's destiny is fixed from eternity, irrespective of any conditions.

Soon after his conversion he felt it to be his duty to preach the gospel, but strove against the impressions with great resolution. But the impressions followed him, and in order to get away from this duty, and the darkness of mind produced by his rebellion against God, he was greatly tempted to commit suicide, and at one time went out into the darkness to end his existence. Some influence, however, kept him from committing the deed. To drown these feelings he married, and married one who, like himself, was sternly opposed to his trying to be a preacher. He also joined the army in 1812 under Col. Young Ewing. The expedition was against the Indians in Illinois. The regiment marched to Fort Clark, found no Indians, and returned to Kentucky nearly starved for food. Col. Ewing was brother to Rev. Finis Ewing, one of the fathers of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. Finis Ewing was himself in the regiment as soldier and chaplain. Mr. Berry again entered the army, and was in the celebrated battle of New Orleans, fought on the 8th of January, 1815. It was in this battle, exposed to instant death, with men falling all around him, that Mr. Berry promised God, if spared to return home, he would serve him to the best of his ability in any position he called him. His soul at that time was filled with inexpressible delight and joy.

In 1817 Mr. Berry was received as a candidate under the care of Logan Presbytery. In the Fall of 1819 he was licensed to preach the gospel, and in 1822 he was ordained to the whole work of the gospel ministry. In 1820 he removed to the State of Indiana, where, like all other poor people, he labored on a farm to support his family and preached what he could. Shortly after his ordination he came to Illinois, and was one of the three members who formed the first Presbytery, as recorded elsewhere. He settled in Sangamon county (at that day but sparsely settled), and he was the only preacher of our people in all the northern part of the State. He continued a member of Illinois Presbytery until, in the Spring of 1829, Sangamon Presbytery held its first meeting, and he was one of its five ministers present. He lived and labored in this field for many years with wonderful success. In the latter part of his life he was a member, we think, of Mackinaw Presbytery, and remained so till his death, which occurred in the Winter of 1856 and 1857, at his residence in Clinton, DeWitt county. His last sermon was delivered at old Sugar Creek, in Logan county, some ten miles north of Lincoln, from Rom viii. 28. He died as he had lived: with his armor on, and in the field of battle.

Mr. Berry was a very positive man. His opinions were very decided, and his preaching was bold, frank, unvarnished. The writer first met him in the town of Greenfield, at the session of Sangamon Presbytery in 1854, only a little over two years before his death. He was very impressive as a speaker. His points were made clear and strong, and he was a man of large influence over the entire State. We had the impression that no man of his day, if we may except Rev. Mr. McLin, had as much to do in forming the character and establishing the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in Illinois as had Mr. Berry.

In the latter part of his life he entertained extreme views on the subject of baptism, which crippled his influence with a portion of the Church. In his early ministry he was in the habit of baptizing often by immersion, if the subject preferred this mode. This, indeed, was the common practice thirty years ago. Mr. Berry had a case of this kind. It was a lady. The season was dry and sufficient water was hard to procure. The baptism was delayed some hours, certain parties having to dam up a little stream so as to accumulate water enough to immerse the body. Mr. Berry felt that he and the entire audience were placed under very embarrassing circumstances. It led him to a careful examination of the subject as to whether God required a mode which, many times, places the subject and administrator under embarrassments like those under which they were laboring. His mind underwent a great revolution on this question, and he came to the firm conviction that immersion is not baptism at all; that all who are immersed are yet unbaptized, and consequently are not in the Church at all--baptism, as he viewed it, being the door into the visible Church. Mr. Berry was not a man to believe strongly in the necessity and importance of a dogma, and not preach it. Accordingly, he preached and argued his new doctrine far and near, producing at the time quite a sensation among the churches of his Presbytery and Synod. So far did he carry his view that he refused to administer the sacrament of the Supper to those who had been immersed, alleging that they were unbaptized, and therefore had no right to partake of the Lord's Supper. About this time he published his book entitle, "The Covenants," in which the doctrine just mentioned is strongly urged. Before the close of his life he seemed to lose sight, somewhat, of this theme, and go back to the themes of his younger days in the ministry; and the excitement over his theory had well nigh died out.

Mr. Berry was very prompt in his attendance upon the judicatories of the Church. He was never absent unless positively hindered by sickness or death, often riding from one hundred to five hundred miles to get there, and that, too, over swollen streams and through mud and almost boundless prairies, many times without any road as a guide to the place of destination. He was a man of great courage and perseverance, of unquestioned integrity, and of spotless character. There was one thing which seemed to trouble him more than all else, and that was a son, who became dissipated. Mr. Berry was much from home, and it appears that while not under the immediate eye of his father, the son acquired a taste for strong drink. This, with its attendant evils, gave the parents much anxiety, and even anguish of mind. Dr. Beard relates an incident connected with this son's case, which we think worthy of repeating here. We may here state, that no man could have been more opposed to intemperance, or a stronger advocate of total abstinence from all intoxicating drinks as a beverage, than was Mr. Berry. His was an uncompromising war upon the enemy at all times. But to the incident: "Abraham Lincoln and Mr. Berry's prodigal son were at one time partners in a little store. It is not so stated, but we should infer from the narrative that they probably sold whisky. Although Mr. Berry could not overcome the obstinacy of his son, he seems to have succeeded with the partner. On one occasion afterward, when Mr. Lincoln had risen to some eminence as a lawyer, a grog shop in a particular neighborhood was exerting a bad influence upon some husbands. The wives of these men united their forces, assailed the establishment, knocked the heads out of the barrels, broke the bottles, and smashed up things generally. The women were prosecuted, and Mr. Lincoln volunteered his services in their defense. In the course of a powerful argument upon the evils of the use of, and of the traffic in, ardent spirits, whilst many in the crowded court room were bathed in tears, the speaker turned, and, pointing his bony finger towards Mr. Berry, who was standing near him, said: 'There is the man who, years ago, was instrumental in convincing me of the evils of trafficing in the using ardent spirits. I am glad that I ever saw him. I am glad that I ever heard his testimony on this terrible subject.'" Several years ago, while traveling in that part of the State in company with another minister, he pointed out to the writer the spot by the roadside where stood the little store referred to by Dr. Beard. Mr. Lincoln is not the only great man in political circles who has received some good influences from the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. Dr. Beard concludes this incident by saying, that Mr. Berry "was more honored that day than he would have been afterwards had he been made Mr. Lincoln's Secretary of State." And so he was.

We did not meet with Mr. Berry but two or three times prior to his death. The last time we saw him was at the meeting of Sangamon Synod the year before his death. he preached on the occasion a good, strong sermon, attended with warmth and energy. The impression made upon the mind of the writer was, that Mr. Berry was a plain, pointed, gospel preacher, seeking no display, desiring no applause from men. And when he was fully enlisted in his subject, he was powerful, and sometimes almost irresistible. He did a great and glorious work, and has gone to his rest and reward.

The Rev. John M. Berry

1788-1856

The Rev. John M'Cutchen Berry is a minister of special interest to this community, not only because he was here to help organize the first presbytery, but because he was related to the Johnsons, who have had members in this church since the beginning in 1819. The Rev. Berry before his conversion was in the War of 1812. The bullets were flying all around him in battle, and he promised the Lord that if He spared his life, he would preach the Gospel, a duty he had tried to escape. He was ordained in 1822, and soon came to Illinois. He was a very positive man, and his preaching was bold, frank, and unvarnished, making him a very impressive speaker. His points were made clear and strong, and he had much influence, over the entire state. He, like the Rev. McLin, did much in forming the character and establishing the Cumberland Presbyterian church in Illinois. His death occurred at Clinton, Illinois.