He was the son of William S. Twining and Margaret Johnson Twining.

13th Annual Reunion Of The Association of the Graduates Of The United States Military Academy, At West Point, New York, June 12, 1882, Times Printing House, Philadelphia.

William Johnston Twining

No. 1998. Class of 1863.

Died May 5, 1882, at Washington, D.C., aged 42.

William Johnston Twining was born at Madison, Indiana, on the 2d of August 1839. On his mother’s side he was descended from the old Dutch settlers of New York and his father was a New England clergyman. About 1835 his parents left New England for the West and settled in Indiana, where his father became a professor in Wabash College at Crawfordsville. The second son, William, was born just before his parents moved to Crawfordsville, but he passed his school days there and prepared to enter Yale College. He had nearly completed his studies for this purpose and went to New Haven during the winter of 1858 and 1859, when his health broke down and he was obliged to suspend his studies. At that time, quite unexpectedly, he was offered the vacant cadetship from his district in Indiana and thinking that the active outdoor life of a military career would be beneficial to his health he determined to accept the appointment. He entered the Military Academy on the 1st of July 1859, in a class of forty-eight members, of whom twenty-five were graduated four years later. The class was a strong one, comprising John R. Meigs, who was killed by guerrillas in the Shenandoah Valley in 1864; Peter S. Michie, the present distinguished professor of philosophy; James D. Rabb, who fell a victim to yellow fever in the Department of the Gulf a few months after graduation; King, Benyard and Howell of the Engineer Corps; McKee, Beebe, Ramsay and Butler, of the Ordnance and others. Meigs was a natural mathematician and easily carried off the first honors; Michie was second, Rabb third and Twining fourth, at graduation.

Graduating in the midst of war the whole class proceeded immediately to the front. Twining was appointed a First Lieutenant in the Engineer Corps and assigned to duty as Assistant Engineer in the Department of the Cumberland, serving under the orders of Colonel W.E. Merrill and General W.F. Smith. He was present at the Battles of Chickamauga and Chattanooga and took part in all the engineering operations along the Tennessee River during the summer and autumn of 1863.

In the spring of 1864 he was appointed Chief Engineer of the Army of the Ohio, commanded by Major General Schofield and soon afterward was appointed a Captain and Aid-de-Camp on that officer’s staff. He remained with General Schofield as his Chief Engineer until the close of the war, participating in all the engagements of the campaign from Chattanooga to Atlanta, thence back to Nashville, in pursuit of Hood, rendering most distinguished service at the Battle of Columbia and gaining a well-earned brevet for gallantry at the Battle of Nashville; thence he was transferred with Schofield’s Corps to North Carolina, where he was engaged in the Battle of Kinston and was present at Johnston’s surrender.

In the summer of 1865 he received what should have been his graduating leave and then reported for duty in the Department of Engineering at the Military Academy, where he received his promotion to a Captaincy in the Engineers. He remained there as principal Assistant Professor in that department until the summer of 1867, when he was ordered to Dakota as Chief Engineer and Aid-de-Camp on General Terry’s staff. He remained in this department, exploring and surveying routes in Dakota, until 1870, his service in that bracing climate proving of great benefit to his health and giving him that appearance of robust strength which was his characteristic until within three days of his death.

After a year’s service on light house duty on the southern coast and another year with the battalion at Willet’s Point, he was ordered, in June 1872, to the Joint Commission for the Survey and Demarcation of the Northern Boundary Line of the United States and upon the retirement of Major Farquhar, a short time afterward, he became Chief Astronomer of the Commission. In that capacity he directed all the astronomical, geodetic and topographical observations necessary for marking the line of the 49th parallel from the Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains, a distance of over eight hundred miles and had practical charge of the fitting out and working of all parties in the field during four seasons and of the office work necessary for the preparation of the maps and reports of the Commission. This work was completed in the summer of 1876 and its records are a standard source of reference for correct methods of executing work of that character. He was then directed to verify the lengths of the Union and Central Pacific Railroads and was subsequently assigned to duty in the office of the Chief of Engineers, where he received his promotion to Major in October 1877.

In the summer of 1878, Congress passed an act to provide a permanent form of government for the District of Columbia, this district being placed by the Constitution within the exclusive jurisdiction of Congress. The essential features of this act were, while reserving to Congress all legislative functions, to place all executive duties necessary for the government of the District in the hands of three Commissioners, to be appointed by the President; one of whom was to be chosen from the Engineers Corps of the Army and while performing his share of the ordinary administrative duties, to have special charge of all public works, subject to District control.

No higher compliment was ever paid by Congress to the Engineer Corps, than in directing that the most responsible member of the Governing Board of the nation’s capital city should be chosen from its ranks. It was an office which involved all the varied and complicated functions of municipal government, - the relations of taxpayers to the city authorities, the nature of assessments for improvements, the public education of children, the administration of Police, Fire, Street, Health and other departments, incidental to every city; in short, the management of a joint estate yielding over $3,000,000 of annual revenue and the care of the public interest of nearly 200,000 people. In its technical aspect it involved the expenditure, on correct principles of engineering, of nearly a million of dollars annually for public works, such as sewerage, pavements, water supply, etc. Such an office required spotless integrity beyond cavil and suspicion, fearless courage in administering trusts for the public interest, - and not in the interest of individuals or corporations – and executive and professional capacity of the highest order. Having no political party nor popular will at his support, but, on the contrary, regarded at first as an alien appointed to govern without any consent of the governed, the incumbent of such an office could be successful only by the strictest regard to the public duty in the interest of the governed. A fierce light would shine upon the office at all times and the public press, as well as the committees of Congress, would be ever ready to crush any incumbent who should either display the haughtiness of an autocrat or give the discontented or disappointed an opportunity for just complaint by swerving in the slightest degree from the strict path of duty.

When the President called upon the Chief of Engineers in June 1878, to select an officer for the duty named in the Act above quoted, General Humphreys immediately nominated Major Twining and he was at once appointed and entered upon his duties on July 1, 1878; though he had then been in Washington for nearly four years, yet he was a comparative stranger to the citizens whose affairs he was called upon to administer nor was he free from the imperfections to which human nature is subject; yet some idea of how closely he approached the ideal standard which we have sketched above may be gathered from the fact that when three years later, an intrigue was set on foot to cause his removal, it was met by a spontaneous and energetic remonstrance on the part of the most influential and respectable citizens. Drawing up a petition, in which they stated that they had heard with alarm of his intended removal, one hundred of the principal citizens of Washington, headed by one of the foremost members of the bar and followed by the principal representatives of every profession and business, without regard to political or other forms of opinion, proceeded in a body to the President, to express their unbounded confidence in Major Twining and their earnest appeal that he should not be removed. No delegation of such strength and respectability had ever visited the President on behalf of any individual connected with the local affairs of Washington nor had such substantial unanimity of opinion ever been manifested on a similar subject. The question of his removal was immediately dropped.

During Major Twining’s administration he devised and carried well towards completion, a plan for the modification and extension of the city sewerage; he investigated ab initio the whole theory of roadway pavements and laid miles of them, constructed on novel principles, but of such an agreeable and substantial character, that they have become famous throughout the country; he devised a plan for the extension of the city water works, concerning the details of which there was great diversity of opinion among engineers, but Twining’s plans were adopted in every single features and embodied in an Act of Congress, passed just after his death; finally he drew up, in the face of bitter opposition from interested parties and of much criticism from so called experts, the plan for reclaiming the malarial flats of the Potomac and lived to see his project approved by a Board of Engineers and adopted, after long investigation, by the Committee of Congress, where it is now pending action. These four great projects, all of them of a character novel and outside of the ordinary routine of his profession, were so successfully dealt with as to firmly establish his reputation as one of the most eminent practical engineers in the service. Of his general administrative talents it need only be said that the present form of government for the District was regarded as a mere experiment when he came into it and at his death, four years later, it was regarded as a permanency, there being no desire for a change from a system which he had proved could work so well.

Throughout his service as a Commissioner, Twining had never been able to absent himself for more than two weeks at a time and this at long intervals, - from his arduous duties. In the spring of 1882 he was annoyed with a slight but troublesome cold, which he seemed unable to shake off and the doctors warned him that his system was run down and he needed rest. But it was a busy time; important measures were pending in Congress; he felt able to perform his duties, though not perfectly well and to a casual observer his physique seemed to be the picture of manly strength.

He declined to stop work, thinking that he would be all right again in a few weeks. Returning from a day’s fishing on the Potomac, one Tuesday afternoon, he went to the circus; it was a cold, gusty day and there, or in a horse car or perhaps in his bed, he was subject to some draught of air, which was but the spark needed to ignite the train of powder with which his system, in its depleted state, was undermined. In the morning, it was pleurisy; the next day, it was pneumonia; the third afternoon, it was death.

It had been my good fortune to serve under his orders, - without once wishing a change, - during the greater part of the last ten years. It was my privilege to watch at his bedside during the few hours of his sickness which ended in death. His critical condition, though not without hope, had been gradually communicated to him during Friday. Sitting there beside him at a few minutes past four o’clock, on Friday afternoon, May 5th, he asked me what the doctors now thought of his chances. I told him that the case was desperate, but they hoped and believed they could keep him alive till morning and if they succeeded, a change for the better was then certain. He answered: I know just how I stand. I am not afraid. After some slight directions about his personal affairs, he muttered again: I am not afraid. Have me buried at West Point. Then with a convulsive gasp for breath he was dead. It was a fearless death, as it had been a memorable life. I am not afraid. That was the sum and all of his faith and no man in his last hour can say more. No man can die with those words on his lips who has on his conscience aught of remorse or memory of wrong done to fellow man. It is the deeds and not the creed, of this life, which determine the hereafter and in the calm confidence of having done no willful wrong he passed without fear or trembling from the petty realities of this life into what he considered the boundless uncertainties of the unseen world.

He was buried from St. John’s Church with the honors befitting his rank of a Civil Governor. His coffin was heaped with the flowers of hundreds of friends, who for three days had besieged his door for news of his condition; solemn and impressive music was sung by the choral club of which he had been the leading member; the President of the United States and members of his Cabinet, Senators and Representatives, who had so often asked his advice in committee; the Judges of the Courts of the District, his associates in the Army and Navy, his friends in every walk in life – thronged the quaint old church and among them, shrouded in the weeds of sorrow, sat the one who was soon to have been his wife. The services and the occasion were inexpressibly sad; why this one, in the pride of health and in the full career of highest usefulness, should be taken and so many left, was the thought which filled every one present. Outside the church could be heard the tramp of the troops of the escort taking their places in line and presently the procession was formed. It was headed by all the troops of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps and Militia, present in the city; it was followed by the President and Cabinet, by his colleagues on the Board of Commissioners, by the whole body of his subordinates, by civic bodies, by his friends. And thus, on a beautiful May day, his mortal remains moved through the streets of the city he had done so much to make beautiful and where fully thirty thousand people now stood on the curbs and in the windows to add each their mite of respect for his memory and of sorrow for their loss.

A few of his friends and late subordinates were delegated to accompany his remains to West Point and there, under the shelter of that grand old school, whose teachings and traditions have made us graduates all that we are and the veneration and love for which comes ever strongest to us in the hour of death, he was laid to rest.

To Washington City his loss seemed, as far as that word can apply to any one of a world of ever dying men, irreparable. It certainly was a public calamity. He had unbounded confidence of its citizens; he was cognizant of and deferential to their wishes. He was in the midst of half completed projects, which to them are of vital interest. To the Army at large and to the Corps of Engineers in particular, his death was such a misfortune as happens only when one of its most distinguished officers fall in the high tide of successful accomplishment, - such a calamity as reaches its highest expression in the death of a McPherson in mid Battle. In the language of his colleagues Endowed with a noble and generous nature and with eminent talents, genial, faithful and truthful in public and private relations, his career, though short, has been distinguished in the military and civil service of his country and his loss will be sincerely mourned by his friends and by the public whom he so ably served.

Resolutions of sorrow were adopted by every organized body with whom he had come in contact, by his colleagues of the Board of Commissioners, by his subordinates in the District government, by the committees of Congress, by the courts of the District, by the various clubs and associations of which he was a member. They cannot all be quoted here. Suffice it to give a portion of the Order of the Chief of Engineers: To this office (of District Commissioner) he brought unsullied integrity, sturdy good sense and executive ability of the highest order and for nearly four years he has performed its duties with such rare skill and good judgment that his death is regarded by the community, whose affairs he administered, as a public calamity. Major Twining was distinguished for the gentleness and the strength of his character and his intelligent devotion to duty. No officer of his age has done more to sustain the high reputation of the Corps of Engineers and his sudden death, in the prime of his usefulness, is to his brother officers a personal affliction and to the corps a serious misfortune.

(F.V. Greene.)∼

He was the son of William S. Twining and Margaret Johnson Twining.

13th Annual Reunion Of The Association of the Graduates Of The United States Military Academy, At West Point, New York, June 12, 1882, Times Printing House, Philadelphia.

William Johnston Twining

No. 1998. Class of 1863.

Died May 5, 1882, at Washington, D.C., aged 42.

William Johnston Twining was born at Madison, Indiana, on the 2d of August 1839. On his mother’s side he was descended from the old Dutch settlers of New York and his father was a New England clergyman. About 1835 his parents left New England for the West and settled in Indiana, where his father became a professor in Wabash College at Crawfordsville. The second son, William, was born just before his parents moved to Crawfordsville, but he passed his school days there and prepared to enter Yale College. He had nearly completed his studies for this purpose and went to New Haven during the winter of 1858 and 1859, when his health broke down and he was obliged to suspend his studies. At that time, quite unexpectedly, he was offered the vacant cadetship from his district in Indiana and thinking that the active outdoor life of a military career would be beneficial to his health he determined to accept the appointment. He entered the Military Academy on the 1st of July 1859, in a class of forty-eight members, of whom twenty-five were graduated four years later. The class was a strong one, comprising John R. Meigs, who was killed by guerrillas in the Shenandoah Valley in 1864; Peter S. Michie, the present distinguished professor of philosophy; James D. Rabb, who fell a victim to yellow fever in the Department of the Gulf a few months after graduation; King, Benyard and Howell of the Engineer Corps; McKee, Beebe, Ramsay and Butler, of the Ordnance and others. Meigs was a natural mathematician and easily carried off the first honors; Michie was second, Rabb third and Twining fourth, at graduation.

Graduating in the midst of war the whole class proceeded immediately to the front. Twining was appointed a First Lieutenant in the Engineer Corps and assigned to duty as Assistant Engineer in the Department of the Cumberland, serving under the orders of Colonel W.E. Merrill and General W.F. Smith. He was present at the Battles of Chickamauga and Chattanooga and took part in all the engineering operations along the Tennessee River during the summer and autumn of 1863.

In the spring of 1864 he was appointed Chief Engineer of the Army of the Ohio, commanded by Major General Schofield and soon afterward was appointed a Captain and Aid-de-Camp on that officer’s staff. He remained with General Schofield as his Chief Engineer until the close of the war, participating in all the engagements of the campaign from Chattanooga to Atlanta, thence back to Nashville, in pursuit of Hood, rendering most distinguished service at the Battle of Columbia and gaining a well-earned brevet for gallantry at the Battle of Nashville; thence he was transferred with Schofield’s Corps to North Carolina, where he was engaged in the Battle of Kinston and was present at Johnston’s surrender.

In the summer of 1865 he received what should have been his graduating leave and then reported for duty in the Department of Engineering at the Military Academy, where he received his promotion to a Captaincy in the Engineers. He remained there as principal Assistant Professor in that department until the summer of 1867, when he was ordered to Dakota as Chief Engineer and Aid-de-Camp on General Terry’s staff. He remained in this department, exploring and surveying routes in Dakota, until 1870, his service in that bracing climate proving of great benefit to his health and giving him that appearance of robust strength which was his characteristic until within three days of his death.

After a year’s service on light house duty on the southern coast and another year with the battalion at Willet’s Point, he was ordered, in June 1872, to the Joint Commission for the Survey and Demarcation of the Northern Boundary Line of the United States and upon the retirement of Major Farquhar, a short time afterward, he became Chief Astronomer of the Commission. In that capacity he directed all the astronomical, geodetic and topographical observations necessary for marking the line of the 49th parallel from the Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains, a distance of over eight hundred miles and had practical charge of the fitting out and working of all parties in the field during four seasons and of the office work necessary for the preparation of the maps and reports of the Commission. This work was completed in the summer of 1876 and its records are a standard source of reference for correct methods of executing work of that character. He was then directed to verify the lengths of the Union and Central Pacific Railroads and was subsequently assigned to duty in the office of the Chief of Engineers, where he received his promotion to Major in October 1877.

In the summer of 1878, Congress passed an act to provide a permanent form of government for the District of Columbia, this district being placed by the Constitution within the exclusive jurisdiction of Congress. The essential features of this act were, while reserving to Congress all legislative functions, to place all executive duties necessary for the government of the District in the hands of three Commissioners, to be appointed by the President; one of whom was to be chosen from the Engineers Corps of the Army and while performing his share of the ordinary administrative duties, to have special charge of all public works, subject to District control.

No higher compliment was ever paid by Congress to the Engineer Corps, than in directing that the most responsible member of the Governing Board of the nation’s capital city should be chosen from its ranks. It was an office which involved all the varied and complicated functions of municipal government, - the relations of taxpayers to the city authorities, the nature of assessments for improvements, the public education of children, the administration of Police, Fire, Street, Health and other departments, incidental to every city; in short, the management of a joint estate yielding over $3,000,000 of annual revenue and the care of the public interest of nearly 200,000 people. In its technical aspect it involved the expenditure, on correct principles of engineering, of nearly a million of dollars annually for public works, such as sewerage, pavements, water supply, etc. Such an office required spotless integrity beyond cavil and suspicion, fearless courage in administering trusts for the public interest, - and not in the interest of individuals or corporations – and executive and professional capacity of the highest order. Having no political party nor popular will at his support, but, on the contrary, regarded at first as an alien appointed to govern without any consent of the governed, the incumbent of such an office could be successful only by the strictest regard to the public duty in the interest of the governed. A fierce light would shine upon the office at all times and the public press, as well as the committees of Congress, would be ever ready to crush any incumbent who should either display the haughtiness of an autocrat or give the discontented or disappointed an opportunity for just complaint by swerving in the slightest degree from the strict path of duty.

When the President called upon the Chief of Engineers in June 1878, to select an officer for the duty named in the Act above quoted, General Humphreys immediately nominated Major Twining and he was at once appointed and entered upon his duties on July 1, 1878; though he had then been in Washington for nearly four years, yet he was a comparative stranger to the citizens whose affairs he was called upon to administer nor was he free from the imperfections to which human nature is subject; yet some idea of how closely he approached the ideal standard which we have sketched above may be gathered from the fact that when three years later, an intrigue was set on foot to cause his removal, it was met by a spontaneous and energetic remonstrance on the part of the most influential and respectable citizens. Drawing up a petition, in which they stated that they had heard with alarm of his intended removal, one hundred of the principal citizens of Washington, headed by one of the foremost members of the bar and followed by the principal representatives of every profession and business, without regard to political or other forms of opinion, proceeded in a body to the President, to express their unbounded confidence in Major Twining and their earnest appeal that he should not be removed. No delegation of such strength and respectability had ever visited the President on behalf of any individual connected with the local affairs of Washington nor had such substantial unanimity of opinion ever been manifested on a similar subject. The question of his removal was immediately dropped.

During Major Twining’s administration he devised and carried well towards completion, a plan for the modification and extension of the city sewerage; he investigated ab initio the whole theory of roadway pavements and laid miles of them, constructed on novel principles, but of such an agreeable and substantial character, that they have become famous throughout the country; he devised a plan for the extension of the city water works, concerning the details of which there was great diversity of opinion among engineers, but Twining’s plans were adopted in every single features and embodied in an Act of Congress, passed just after his death; finally he drew up, in the face of bitter opposition from interested parties and of much criticism from so called experts, the plan for reclaiming the malarial flats of the Potomac and lived to see his project approved by a Board of Engineers and adopted, after long investigation, by the Committee of Congress, where it is now pending action. These four great projects, all of them of a character novel and outside of the ordinary routine of his profession, were so successfully dealt with as to firmly establish his reputation as one of the most eminent practical engineers in the service. Of his general administrative talents it need only be said that the present form of government for the District was regarded as a mere experiment when he came into it and at his death, four years later, it was regarded as a permanency, there being no desire for a change from a system which he had proved could work so well.

Throughout his service as a Commissioner, Twining had never been able to absent himself for more than two weeks at a time and this at long intervals, - from his arduous duties. In the spring of 1882 he was annoyed with a slight but troublesome cold, which he seemed unable to shake off and the doctors warned him that his system was run down and he needed rest. But it was a busy time; important measures were pending in Congress; he felt able to perform his duties, though not perfectly well and to a casual observer his physique seemed to be the picture of manly strength.

He declined to stop work, thinking that he would be all right again in a few weeks. Returning from a day’s fishing on the Potomac, one Tuesday afternoon, he went to the circus; it was a cold, gusty day and there, or in a horse car or perhaps in his bed, he was subject to some draught of air, which was but the spark needed to ignite the train of powder with which his system, in its depleted state, was undermined. In the morning, it was pleurisy; the next day, it was pneumonia; the third afternoon, it was death.

It had been my good fortune to serve under his orders, - without once wishing a change, - during the greater part of the last ten years. It was my privilege to watch at his bedside during the few hours of his sickness which ended in death. His critical condition, though not without hope, had been gradually communicated to him during Friday. Sitting there beside him at a few minutes past four o’clock, on Friday afternoon, May 5th, he asked me what the doctors now thought of his chances. I told him that the case was desperate, but they hoped and believed they could keep him alive till morning and if they succeeded, a change for the better was then certain. He answered: I know just how I stand. I am not afraid. After some slight directions about his personal affairs, he muttered again: I am not afraid. Have me buried at West Point. Then with a convulsive gasp for breath he was dead. It was a fearless death, as it had been a memorable life. I am not afraid. That was the sum and all of his faith and no man in his last hour can say more. No man can die with those words on his lips who has on his conscience aught of remorse or memory of wrong done to fellow man. It is the deeds and not the creed, of this life, which determine the hereafter and in the calm confidence of having done no willful wrong he passed without fear or trembling from the petty realities of this life into what he considered the boundless uncertainties of the unseen world.

He was buried from St. John’s Church with the honors befitting his rank of a Civil Governor. His coffin was heaped with the flowers of hundreds of friends, who for three days had besieged his door for news of his condition; solemn and impressive music was sung by the choral club of which he had been the leading member; the President of the United States and members of his Cabinet, Senators and Representatives, who had so often asked his advice in committee; the Judges of the Courts of the District, his associates in the Army and Navy, his friends in every walk in life – thronged the quaint old church and among them, shrouded in the weeds of sorrow, sat the one who was soon to have been his wife. The services and the occasion were inexpressibly sad; why this one, in the pride of health and in the full career of highest usefulness, should be taken and so many left, was the thought which filled every one present. Outside the church could be heard the tramp of the troops of the escort taking their places in line and presently the procession was formed. It was headed by all the troops of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps and Militia, present in the city; it was followed by the President and Cabinet, by his colleagues on the Board of Commissioners, by the whole body of his subordinates, by civic bodies, by his friends. And thus, on a beautiful May day, his mortal remains moved through the streets of the city he had done so much to make beautiful and where fully thirty thousand people now stood on the curbs and in the windows to add each their mite of respect for his memory and of sorrow for their loss.

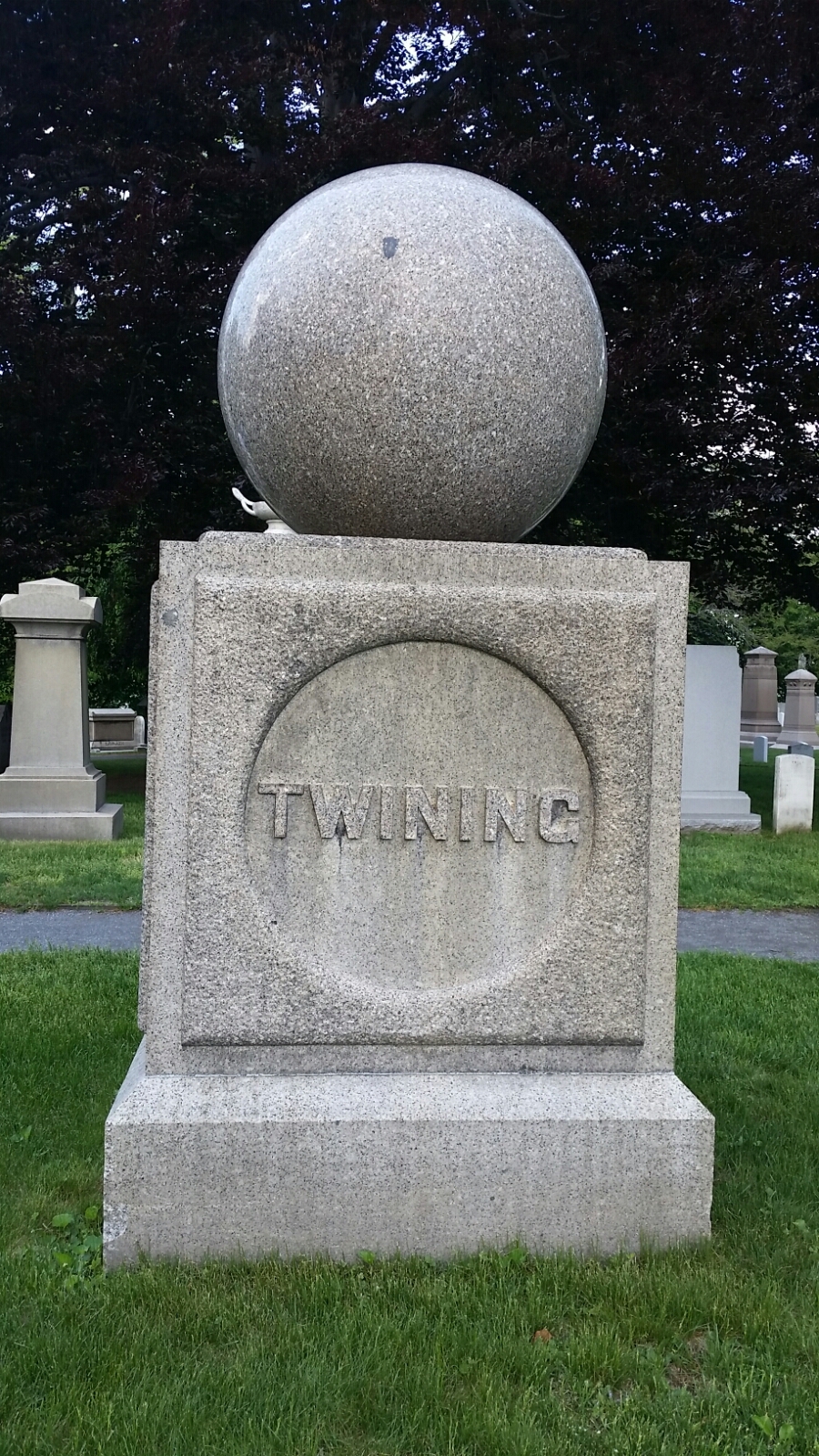

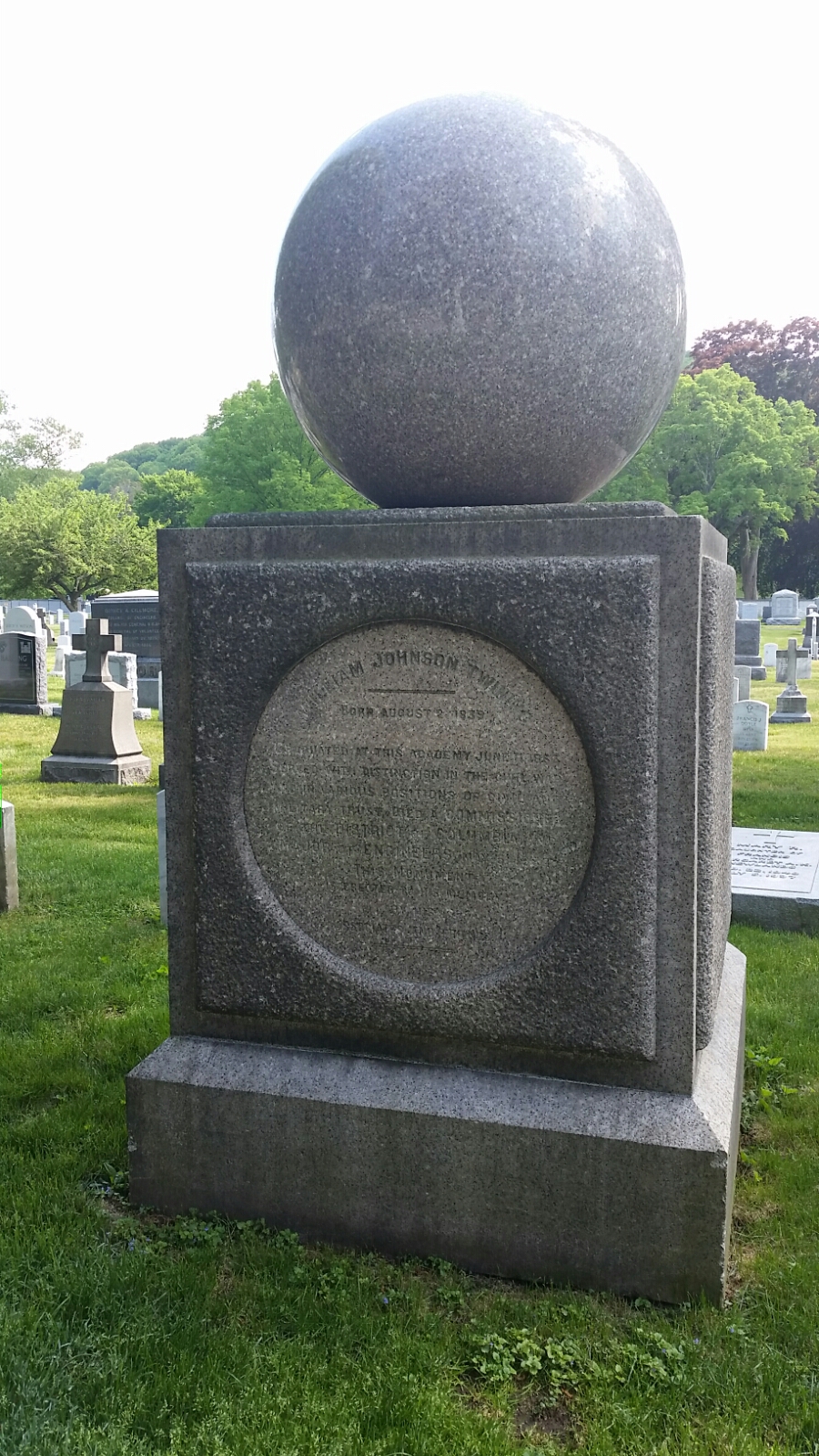

A few of his friends and late subordinates were delegated to accompany his remains to West Point and there, under the shelter of that grand old school, whose teachings and traditions have made us graduates all that we are and the veneration and love for which comes ever strongest to us in the hour of death, he was laid to rest.

To Washington City his loss seemed, as far as that word can apply to any one of a world of ever dying men, irreparable. It certainly was a public calamity. He had unbounded confidence of its citizens; he was cognizant of and deferential to their wishes. He was in the midst of half completed projects, which to them are of vital interest. To the Army at large and to the Corps of Engineers in particular, his death was such a misfortune as happens only when one of its most distinguished officers fall in the high tide of successful accomplishment, - such a calamity as reaches its highest expression in the death of a McPherson in mid Battle. In the language of his colleagues Endowed with a noble and generous nature and with eminent talents, genial, faithful and truthful in public and private relations, his career, though short, has been distinguished in the military and civil service of his country and his loss will be sincerely mourned by his friends and by the public whom he so ably served.

Resolutions of sorrow were adopted by every organized body with whom he had come in contact, by his colleagues of the Board of Commissioners, by his subordinates in the District government, by the committees of Congress, by the courts of the District, by the various clubs and associations of which he was a member. They cannot all be quoted here. Suffice it to give a portion of the Order of the Chief of Engineers: To this office (of District Commissioner) he brought unsullied integrity, sturdy good sense and executive ability of the highest order and for nearly four years he has performed its duties with such rare skill and good judgment that his death is regarded by the community, whose affairs he administered, as a public calamity. Major Twining was distinguished for the gentleness and the strength of his character and his intelligent devotion to duty. No officer of his age has done more to sustain the high reputation of the Corps of Engineers and his sudden death, in the prime of his usefulness, is to his brother officers a personal affliction and to the corps a serious misfortune.

(F.V. Greene.)∼

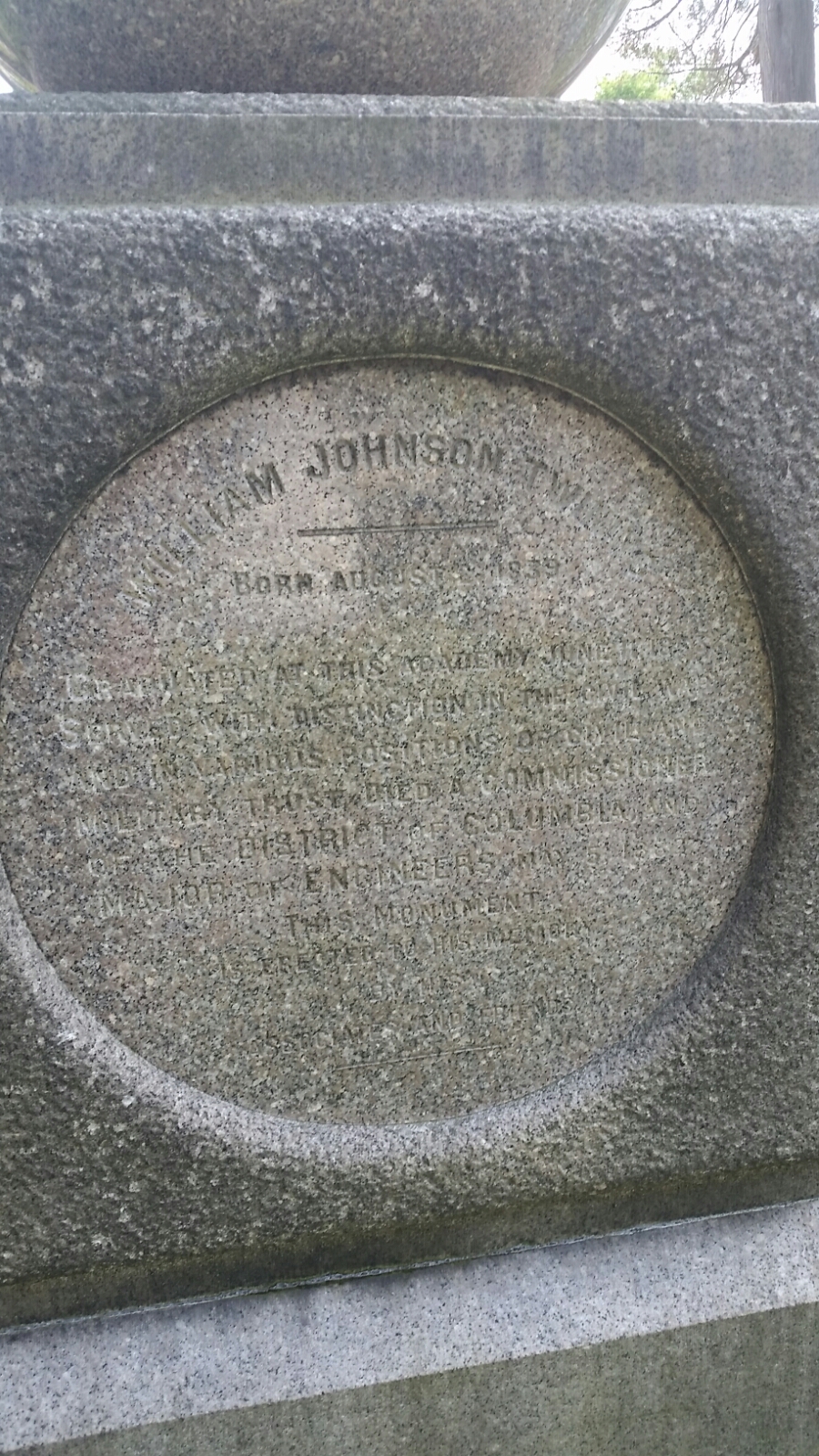

Inscription

William Johnson Twining

Born August 2 1839

Graduated At This Academy June 11 1863.

Served With Distinction In The Civil War And In Various Positions Of Civil And Military Trust. Died A Commissioner Of The District Of Columbia And Major Of Engineers May 5th 1882.

This Monument

Is Erected To His Memory

By His Associates And Friends.

Family Members

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement