Fred Lockley, "Impressions and Observations of the Journal Man" Oregon Journal, 28 August 1929

"When I retired from the photographic profession,' said Benjamin A. Gifford to me recently, 'I turned over all my plates but one. That one is a picture of the Columbia river at sunset. In the background is a line of Lombardy poplars. The setting sun makes a path of gold on the majestic Columbia. In the immediate foreground is an Indian dugout, hollowed from some tree that once grew on the shores of the Columbia. Two teepees are pitched on the rounded and water-washed gravel near the river. The reason I wanted to keep this negative was because of its association. I believe it is the most artistic picture I had ever taken and I took it under rather peculiar circumstances.

'I had gone up near Maryhill, which was then called Columbus, to photograph a band of sheep being driven to the railroad. After getting my sheep pictures, I went down to the river bank. The river seemed illuminated with subterranean light. The sun was setting; the shadows were gathering over the hills. Beside the river were two teepees. A dugout was drawn up on the river's bank. No Indians were in sight. As I turned my back on the teepees to take the cap off my camera, a rock struck close to me. I turned quickly, but couldn't see anyone. Once more I turned my back, and a rock whizzed by my head. Dropping the black cloth which I had over my arm, I reached in my back pocket and ran toward one of the teepees. Two Indians, who had been hiding back of the teepees, bolted, I went back to my camera and secured the picture. When I showed the picture to an Indian, he said, 'Wa-ne-ka,' which, as near as I can find out, means 'the sun going down of the evening sun,' or 'the halo of the evening sun.'

'I have photographed untold numbers of Indians, and this was the first time I ever had any trouble in photographing Indians. One time the photographers of the state assembled in convention at Portland. They came up to The Dalles on an excursion, on a steamer. On their return there were a lot of Indians aboard, dressed up in their finery, going to the exposition in Portland, The photographers were wild to take pictures of these Indians, but they shook their heads, and said, 'No take our picture, Gifford – he takes our pictures; nobody else.'

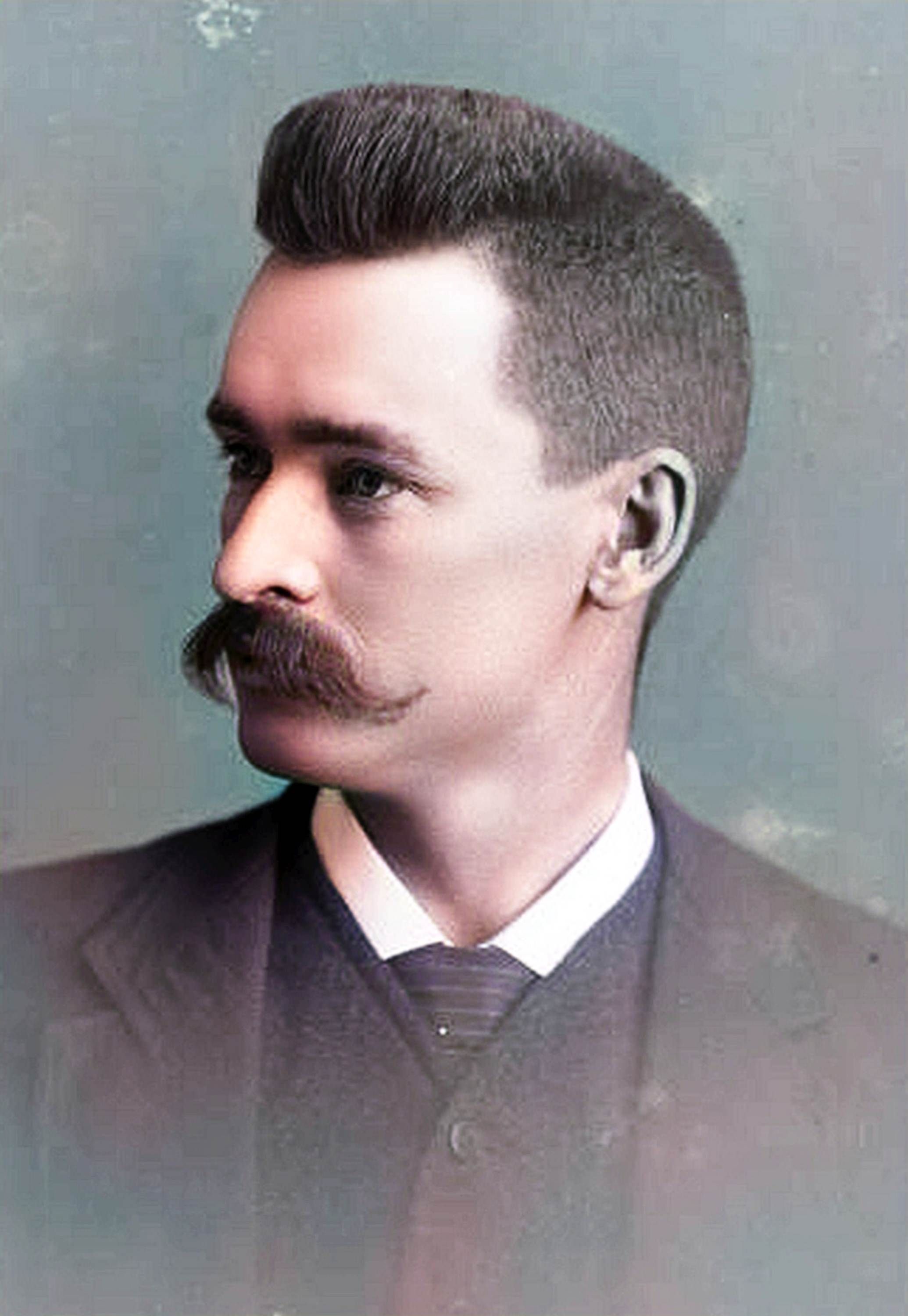

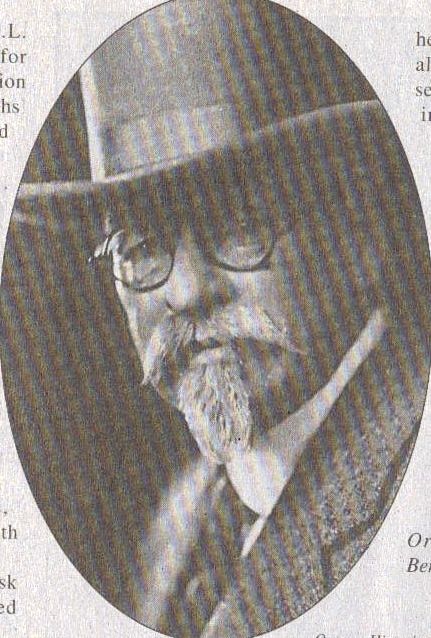

'I want you to come out to my place at Wa-ne-ka, on Salmon creek, on the Pacific highway, five miles north of Vancouver. I want to show you photographs of how the place looked when I took it some years ago, and I want you to see what it looks like now. Working outdoors restored my health and made me feel 10 years younger. I was 70 years old on August 11. I was born in Illinois. My father, Harvey D. Gifford, traveled all over that part of Illinois conducting singing schools. He taught vocal music for more than 40 years. My mother's maiden name was Marletta Corbin. I am the youngest of their four children. My brother Corbin lives in Springfield, Mo. I had very little schooling before I was 21 years of age. Father sold the farm when I was 21 and I went to the Kansas normal college at Fort Scott for a year or two. Later I put in two years as an apprentice in a photograph gallery there. From Fort Scott I went to Sedalia, Mo., to finish my four years' apprenticeship under William LaTour. Returning to Fort Scott, I became a partner of E. P. Tressler in a studio there. After two years I sold out and went to Chetopa, Kan., which is located on the Indian Territory line.

'A friend of mine named Brundage had come out to Oregon and was working for the O. R. & N. company. He liked it so much out here that I decided to go West. I came to Portland in the summer of 1888, and started a studio diagonally across the street from the Hotel Portland, in a two-story building on the corner of Sixth and Morrison.

'A person doesn't have to take a four years' apprenticeship nowadays to become a photographer, but 50 years ago, when I first became interested in photography, the process was much more complicated. Dry plates were just beginning to come in, but the old-time photographers were doubtful of them. When we went out to take scenic views or pictures away from the gallery we had to carry all our equipment with us. In those days our plate was a plain piece of glass. You held the plate in one hand, poured collodian over it, and then immersed it in a silver bath. You exposed the plate while it was still wet, and had to develop it at once, before it got dry. Your paper on which the photographs were printed was albumenized and you had to silver your own paper.

I was the first photographer in Portland who ever made an enlargement of a photograph by electric light. In those days we had no daylight electric service. The electric light was not turned on until dusk, so I had to make all enlargements at night.

'I became tremendously interested in the Columbia river. I was the first person to get out an album of Columbia river views. I called this album 'Snapshots on the Columbia.' The photogravure views were 5×8 and accompanying each photograph was a page of text telling of the legends of the Columbia river Indians. From Portland I moved up to The Dalles, where I operated a studio for 15 years. It was at The Dalles that I began taking pictures of the Indians.

'One time I took a picture of the wheat fields near Dufur. I brought it to Portland and showed it to A. L. Craig, general passenger agent of the O. R. & N. I said to him, 'A few hundred pictures like this, scattered throughout the East, will do more to bring farmers and settlers to Oregon than all the books you can print.' He agreed with me, and for years I furnished enlarged photographs of scenic views and farm scenes to the railroad companies.

'You have probably seen the large book I have out entitled 'Art Work of Oregon.' It sold for $40. For years the Oregon Journal published a full-page picture of mine each Sunday in their magazine section. In about 1910 I sold my gallery at The Dalles to Charlie Lamb and moved to Portland. In 1920 I moved to my present place at Wa-ne-ka, in Clark county, Washington. In 1901 I took a picture of Mount Hood from Lost Lake. I have sold thousands of copies of that and have sent them all over the world. I was offered and refused $1000 for the negative. My son Ralph, who served in the navy during the World war, ran a gallery for some years at White River, at the foot of Mount Hood. He is now in the moving picture business."

Contributor: Outespace (49815106)

Fred Lockley, "Impressions and Observations of the Journal Man" Oregon Journal, 28 August 1929

"When I retired from the photographic profession,' said Benjamin A. Gifford to me recently, 'I turned over all my plates but one. That one is a picture of the Columbia river at sunset. In the background is a line of Lombardy poplars. The setting sun makes a path of gold on the majestic Columbia. In the immediate foreground is an Indian dugout, hollowed from some tree that once grew on the shores of the Columbia. Two teepees are pitched on the rounded and water-washed gravel near the river. The reason I wanted to keep this negative was because of its association. I believe it is the most artistic picture I had ever taken and I took it under rather peculiar circumstances.

'I had gone up near Maryhill, which was then called Columbus, to photograph a band of sheep being driven to the railroad. After getting my sheep pictures, I went down to the river bank. The river seemed illuminated with subterranean light. The sun was setting; the shadows were gathering over the hills. Beside the river were two teepees. A dugout was drawn up on the river's bank. No Indians were in sight. As I turned my back on the teepees to take the cap off my camera, a rock struck close to me. I turned quickly, but couldn't see anyone. Once more I turned my back, and a rock whizzed by my head. Dropping the black cloth which I had over my arm, I reached in my back pocket and ran toward one of the teepees. Two Indians, who had been hiding back of the teepees, bolted, I went back to my camera and secured the picture. When I showed the picture to an Indian, he said, 'Wa-ne-ka,' which, as near as I can find out, means 'the sun going down of the evening sun,' or 'the halo of the evening sun.'

'I have photographed untold numbers of Indians, and this was the first time I ever had any trouble in photographing Indians. One time the photographers of the state assembled in convention at Portland. They came up to The Dalles on an excursion, on a steamer. On their return there were a lot of Indians aboard, dressed up in their finery, going to the exposition in Portland, The photographers were wild to take pictures of these Indians, but they shook their heads, and said, 'No take our picture, Gifford – he takes our pictures; nobody else.'

'I want you to come out to my place at Wa-ne-ka, on Salmon creek, on the Pacific highway, five miles north of Vancouver. I want to show you photographs of how the place looked when I took it some years ago, and I want you to see what it looks like now. Working outdoors restored my health and made me feel 10 years younger. I was 70 years old on August 11. I was born in Illinois. My father, Harvey D. Gifford, traveled all over that part of Illinois conducting singing schools. He taught vocal music for more than 40 years. My mother's maiden name was Marletta Corbin. I am the youngest of their four children. My brother Corbin lives in Springfield, Mo. I had very little schooling before I was 21 years of age. Father sold the farm when I was 21 and I went to the Kansas normal college at Fort Scott for a year or two. Later I put in two years as an apprentice in a photograph gallery there. From Fort Scott I went to Sedalia, Mo., to finish my four years' apprenticeship under William LaTour. Returning to Fort Scott, I became a partner of E. P. Tressler in a studio there. After two years I sold out and went to Chetopa, Kan., which is located on the Indian Territory line.

'A friend of mine named Brundage had come out to Oregon and was working for the O. R. & N. company. He liked it so much out here that I decided to go West. I came to Portland in the summer of 1888, and started a studio diagonally across the street from the Hotel Portland, in a two-story building on the corner of Sixth and Morrison.

'A person doesn't have to take a four years' apprenticeship nowadays to become a photographer, but 50 years ago, when I first became interested in photography, the process was much more complicated. Dry plates were just beginning to come in, but the old-time photographers were doubtful of them. When we went out to take scenic views or pictures away from the gallery we had to carry all our equipment with us. In those days our plate was a plain piece of glass. You held the plate in one hand, poured collodian over it, and then immersed it in a silver bath. You exposed the plate while it was still wet, and had to develop it at once, before it got dry. Your paper on which the photographs were printed was albumenized and you had to silver your own paper.

I was the first photographer in Portland who ever made an enlargement of a photograph by electric light. In those days we had no daylight electric service. The electric light was not turned on until dusk, so I had to make all enlargements at night.

'I became tremendously interested in the Columbia river. I was the first person to get out an album of Columbia river views. I called this album 'Snapshots on the Columbia.' The photogravure views were 5×8 and accompanying each photograph was a page of text telling of the legends of the Columbia river Indians. From Portland I moved up to The Dalles, where I operated a studio for 15 years. It was at The Dalles that I began taking pictures of the Indians.

'One time I took a picture of the wheat fields near Dufur. I brought it to Portland and showed it to A. L. Craig, general passenger agent of the O. R. & N. I said to him, 'A few hundred pictures like this, scattered throughout the East, will do more to bring farmers and settlers to Oregon than all the books you can print.' He agreed with me, and for years I furnished enlarged photographs of scenic views and farm scenes to the railroad companies.

'You have probably seen the large book I have out entitled 'Art Work of Oregon.' It sold for $40. For years the Oregon Journal published a full-page picture of mine each Sunday in their magazine section. In about 1910 I sold my gallery at The Dalles to Charlie Lamb and moved to Portland. In 1920 I moved to my present place at Wa-ne-ka, in Clark county, Washington. In 1901 I took a picture of Mount Hood from Lost Lake. I have sold thousands of copies of that and have sent them all over the world. I was offered and refused $1000 for the negative. My son Ralph, who served in the navy during the World war, ran a gallery for some years at White River, at the foot of Mount Hood. He is now in the moving picture business."

Contributor: Outespace (49815106)

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement