Gennaro was one of seven National Guardsmen from the Philadelphia-area killed in one week in Iraq.

From The Philadelphia Inquirer, Wednesday, August 17, 2005:

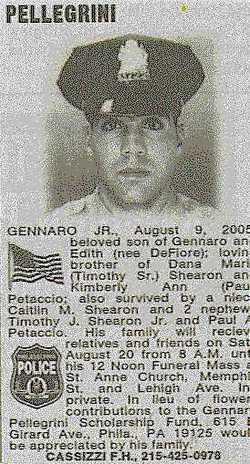

GENNARO, JR., August 9, 2005, beloved son of Gennaro and Edith (nee De Fiore); loving brother of Dana Marie (Timothy, Sr.) Shearon and Kimberly Ann (Paul) Petaccio; also survived by a niece Caitlin M. Shearon and 2 nephews Timothy J. Shearon, Jr. and Paul A. Petaccio. His family will receive relatives and friends on Sat., August 20 from 8 A.M. until his 12 Noon Funeral Mass at St. Anne Church, Memphis St. and Lehigh Ave. Int. private. In lieu of flowers, contributions to the Gennaro Pellegrini Scholarship Fund, 615 E. Girard Ave., Phila. PA 19125 would be appreciated by his family.

Philadelphia Weekly, August 17, 2005 by Frank Rubino:

Gennaro Pellegrini Jr. (1974-2005)

A Philadelphia boxer with a Rocky-like story is killed in Iraq.

The camouflage boxing trunks emblazoned with American flags, military insignias and the name "GENNARO" still hang in the office of Blue Horizon proprietor Vernoca Michael. But soon they'll be placed in the storied Horizon's museum with the gloves, photos of famed fighters and other Philadelphia boxing memorabilia.

The man who wore the trunks, 31-year-old Philadelphia police officer Gennaro Pellegrini Jr., died alongside three fellow Army National Guardsmen last week in Beyji, Iraq. The soldiers' Humvee ran over a bomb, and was then attacked by insurgents brandishing rocket-propelled grenades.

Pellegrini, an aspiring pugilist who made a smashing professional debut at the Blue Horizon in May 2004, won't get to don those trunks for a return engagement. Horizon owner Michael, who loved Pellegrini like a son, regrets that deeply.

"I promised Gerry we'd let him fight here again after he came home," she says. "And of course he would wear those trunks. They were going to hang right here until that time arrived."

Pellegrini, who became a police officer in 2001 and quickly earned numerous commendations as well as the admiration of his colleagues, had other things to look forward to as well. He wanted to get married, to take SWAT team training, to grow older and be like his father, a retired cop who lives with Gennaro's mother Edie at the Jersey shore.

But war has an ugly way of short-circuiting dreams, and it doesn't play favorites. The story of Gennaro Pellegrini Jr. provides a tragic case in point.

Fifteen months ago a PW reporter sat in the living room of a tidy Port Richmond row house, listening as the normally buoyant Pellegrini reflected stoically on a situation that didn't please him.

He'd joined the Guard in 1998, and his six-year commitment was scheduled to end on April 24, 2004. But the Army, facing personnel challenges amid the loss of life in Iraq, extended his enlistment by 18 months under a policy that can delay separations and retirements during wartime and national

emergencies.

"I joined the military," Pellegrini said resignedly that evening, "and I didn't think this was going to happen. But I'm gonna go over there and do the best job I can."

First, however, he had to tend to the matter of his pro boxing debut. Owner Michael and Don Elbaum, the Blue Horizon's matchmaker, enabled Pellegrini to realize that ambition after they learned the hard-punching welterweight, who won a Golden Gloves title in 1997, had fantasized about rumbling at the Blue for years.

So on May 21, 2004, Pellegrini squared off against Andre Harris of Wildwood, N.J., in front of a crowd heavy with cops and soldiers.

The little four-rounder became an epic battle.

"It was a Rocky fight, an absolute war," the colorful Elbaum remembers. "Gerry started out strong. That kid Harris had a lousy record, but he had balls, he fought back, and in the third round Gerry got tired. He was having trouble breathing, and they just pushed him out of his corner for the last round."

That round-and Pellegrini's boxing career, as it turns out-ended when he dug deep within himself to launch one final haymaker, an overhand right that knocked Harris out amid pandemonium.

The following month Pellegrini left for infantry training in Texas. And in December 2004, he and other members of Alpha Company of the First Battalion of the 111th Infantry shipped out for Iraq.

Pellegrini's wartime activities wouldn't befit the faint of heart.

"He manned checkpoints," says Lt. Jay Ostrich, a Pennsylvania National Guard spokesperson. "He went out on patrol, capturing enemy insurgents and turning them over to MPs. He was doing some of the most dangerous work in Iraq."

Capt. Lou Campione, commander of Fishtown's 26th Police District and Pellegrini's boss for four years, is certain the Army couldn't have put a better soldier on the job.

"Everybody here respected him," Campione says. "He not only had your back, he'd jump over you to protect you."

Campione recalls a legendary collar Pellegrini made in 2002, for which the officer chased three robbery suspects north on I-95 at speeds exceeding 100 miles an hour. After they bailed from their car in Northeast Philadelphia, one of the suspects took a swing at Pellegrini, who didn't think he had time to grab his mace. So he decked the guy with the same right that led to his Blue Horizon conquest.

"That's how he got the nickname Gerry 'One-Punch' Pellegrini," Campione relates. "But even though he had the muscle power to conquer situations physically, he never carried himself like a bully. He didn't have to Bogart his way. He tried to bring down the stress level in any situation he was involved in.

"He's a double hero because of the way he conducted himself as a police officer on the streets of Philadelphia and for the sacrifice he made in Iraq for our country. People around here will be talking about him for many, many years."

Michael talked about the fallen soldier the day after he died, huddling with his family and attempting to console them with her spiritual take on tragedy.

"I've always believed we're on loan from the Lord," she says. "And there comes a time when he has another assignment for us. I told [Pellegrini's family] that we have to accept God's decisions. We might not like all of his decisions, but we have to accept them."

The earthy Elbaum views Pellegrini's passing more indignantly. "This shouldn't have happened," he says. "He shouldn't have been there. It's wrong, and it just ain't right."

Gennaro was one of seven National Guardsmen from the Philadelphia-area killed in one week in Iraq.

From The Philadelphia Inquirer, Wednesday, August 17, 2005:

GENNARO, JR., August 9, 2005, beloved son of Gennaro and Edith (nee De Fiore); loving brother of Dana Marie (Timothy, Sr.) Shearon and Kimberly Ann (Paul) Petaccio; also survived by a niece Caitlin M. Shearon and 2 nephews Timothy J. Shearon, Jr. and Paul A. Petaccio. His family will receive relatives and friends on Sat., August 20 from 8 A.M. until his 12 Noon Funeral Mass at St. Anne Church, Memphis St. and Lehigh Ave. Int. private. In lieu of flowers, contributions to the Gennaro Pellegrini Scholarship Fund, 615 E. Girard Ave., Phila. PA 19125 would be appreciated by his family.

Philadelphia Weekly, August 17, 2005 by Frank Rubino:

Gennaro Pellegrini Jr. (1974-2005)

A Philadelphia boxer with a Rocky-like story is killed in Iraq.

The camouflage boxing trunks emblazoned with American flags, military insignias and the name "GENNARO" still hang in the office of Blue Horizon proprietor Vernoca Michael. But soon they'll be placed in the storied Horizon's museum with the gloves, photos of famed fighters and other Philadelphia boxing memorabilia.

The man who wore the trunks, 31-year-old Philadelphia police officer Gennaro Pellegrini Jr., died alongside three fellow Army National Guardsmen last week in Beyji, Iraq. The soldiers' Humvee ran over a bomb, and was then attacked by insurgents brandishing rocket-propelled grenades.

Pellegrini, an aspiring pugilist who made a smashing professional debut at the Blue Horizon in May 2004, won't get to don those trunks for a return engagement. Horizon owner Michael, who loved Pellegrini like a son, regrets that deeply.

"I promised Gerry we'd let him fight here again after he came home," she says. "And of course he would wear those trunks. They were going to hang right here until that time arrived."

Pellegrini, who became a police officer in 2001 and quickly earned numerous commendations as well as the admiration of his colleagues, had other things to look forward to as well. He wanted to get married, to take SWAT team training, to grow older and be like his father, a retired cop who lives with Gennaro's mother Edie at the Jersey shore.

But war has an ugly way of short-circuiting dreams, and it doesn't play favorites. The story of Gennaro Pellegrini Jr. provides a tragic case in point.

Fifteen months ago a PW reporter sat in the living room of a tidy Port Richmond row house, listening as the normally buoyant Pellegrini reflected stoically on a situation that didn't please him.

He'd joined the Guard in 1998, and his six-year commitment was scheduled to end on April 24, 2004. But the Army, facing personnel challenges amid the loss of life in Iraq, extended his enlistment by 18 months under a policy that can delay separations and retirements during wartime and national

emergencies.

"I joined the military," Pellegrini said resignedly that evening, "and I didn't think this was going to happen. But I'm gonna go over there and do the best job I can."

First, however, he had to tend to the matter of his pro boxing debut. Owner Michael and Don Elbaum, the Blue Horizon's matchmaker, enabled Pellegrini to realize that ambition after they learned the hard-punching welterweight, who won a Golden Gloves title in 1997, had fantasized about rumbling at the Blue for years.

So on May 21, 2004, Pellegrini squared off against Andre Harris of Wildwood, N.J., in front of a crowd heavy with cops and soldiers.

The little four-rounder became an epic battle.

"It was a Rocky fight, an absolute war," the colorful Elbaum remembers. "Gerry started out strong. That kid Harris had a lousy record, but he had balls, he fought back, and in the third round Gerry got tired. He was having trouble breathing, and they just pushed him out of his corner for the last round."

That round-and Pellegrini's boxing career, as it turns out-ended when he dug deep within himself to launch one final haymaker, an overhand right that knocked Harris out amid pandemonium.

The following month Pellegrini left for infantry training in Texas. And in December 2004, he and other members of Alpha Company of the First Battalion of the 111th Infantry shipped out for Iraq.

Pellegrini's wartime activities wouldn't befit the faint of heart.

"He manned checkpoints," says Lt. Jay Ostrich, a Pennsylvania National Guard spokesperson. "He went out on patrol, capturing enemy insurgents and turning them over to MPs. He was doing some of the most dangerous work in Iraq."

Capt. Lou Campione, commander of Fishtown's 26th Police District and Pellegrini's boss for four years, is certain the Army couldn't have put a better soldier on the job.

"Everybody here respected him," Campione says. "He not only had your back, he'd jump over you to protect you."

Campione recalls a legendary collar Pellegrini made in 2002, for which the officer chased three robbery suspects north on I-95 at speeds exceeding 100 miles an hour. After they bailed from their car in Northeast Philadelphia, one of the suspects took a swing at Pellegrini, who didn't think he had time to grab his mace. So he decked the guy with the same right that led to his Blue Horizon conquest.

"That's how he got the nickname Gerry 'One-Punch' Pellegrini," Campione relates. "But even though he had the muscle power to conquer situations physically, he never carried himself like a bully. He didn't have to Bogart his way. He tried to bring down the stress level in any situation he was involved in.

"He's a double hero because of the way he conducted himself as a police officer on the streets of Philadelphia and for the sacrifice he made in Iraq for our country. People around here will be talking about him for many, many years."

Michael talked about the fallen soldier the day after he died, huddling with his family and attempting to console them with her spiritual take on tragedy.

"I've always believed we're on loan from the Lord," she says. "And there comes a time when he has another assignment for us. I told [Pellegrini's family] that we have to accept God's decisions. We might not like all of his decisions, but we have to accept them."

The earthy Elbaum views Pellegrini's passing more indignantly. "This shouldn't have happened," he says. "He shouldn't have been there. It's wrong, and it just ain't right."

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

-

U.S., Newspapers.com™ Obituary Index, 1800s-current

-

U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007

-

U.S., Find a Grave® Index, 1600s-Current

-

U.S., Casualties From Iraq and Afghanistan Conflicts, 2001-2012

-

U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement