The newspapers have sent teams of reporters to the East Village. They have visited the scene of the crime and filed their stories:

"A 26-year-old Black Nationalist ex-convict today was charged with the bludgeon slayings of two whites, a teenage socialite and a tattooed hippie, in the basement of an East Village tenement following what police called a 'wild acid party' Saturday night..."

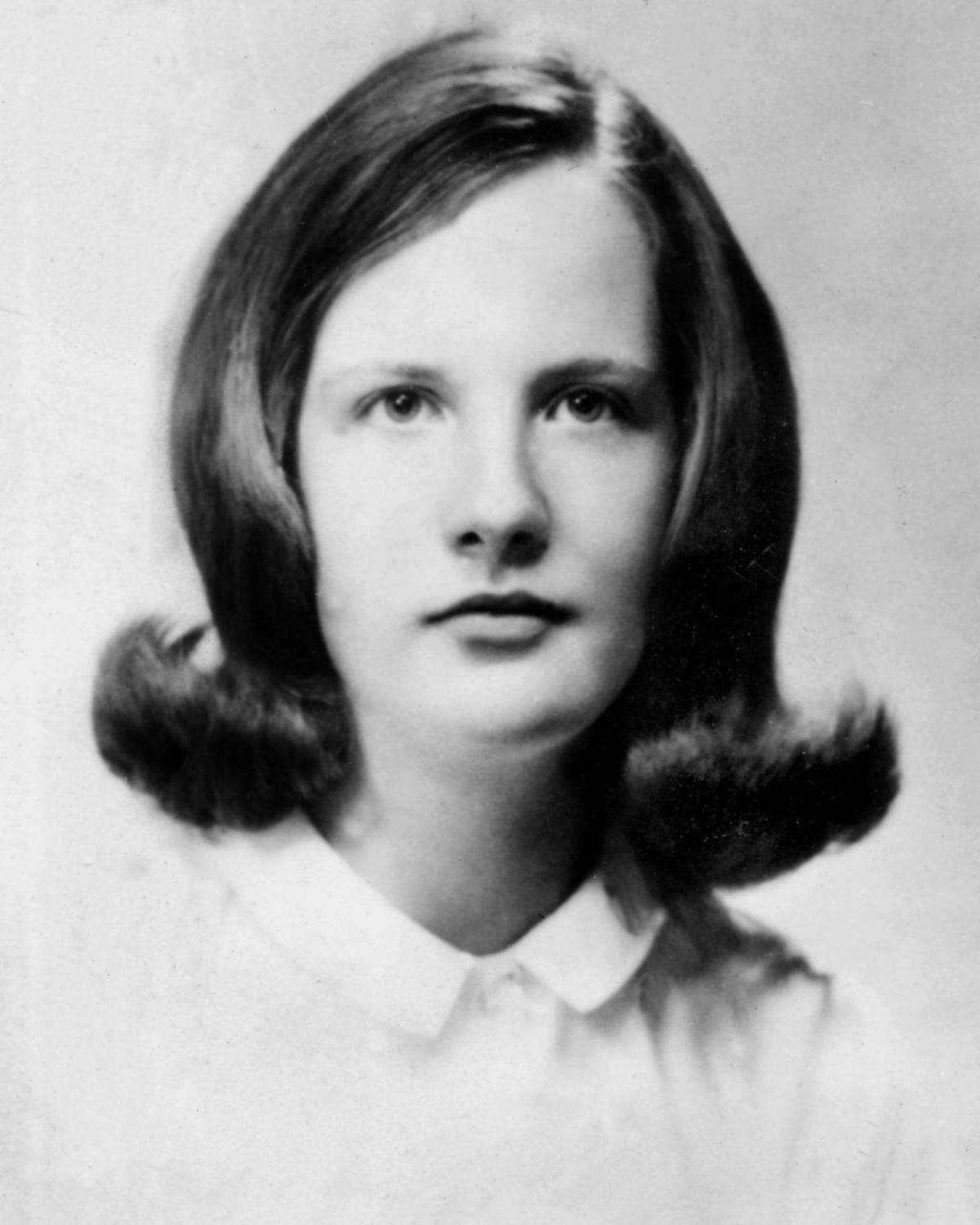

The obituaries of Linda Rae Fitzpatrick, 18, and James Leroy Hutchinson ("Groovy"), 24, will run like that all over the country as a reminder to Americans that freaking-out in the land of the free and the home of the brave can be fatal.

"The published picture of Linda must have been taken in high school," said Galahad, a Digger who was Groovy's closest friend. "It's all wrong. Her hair was blonde and short. She was a happy-go-lucky character -- a really beautiful chick. In one sense she was serious -- almost conservative; in another she was really high on life. In this way she was like Groovy who grooved on life. He didn't really need drugs to keep him high."

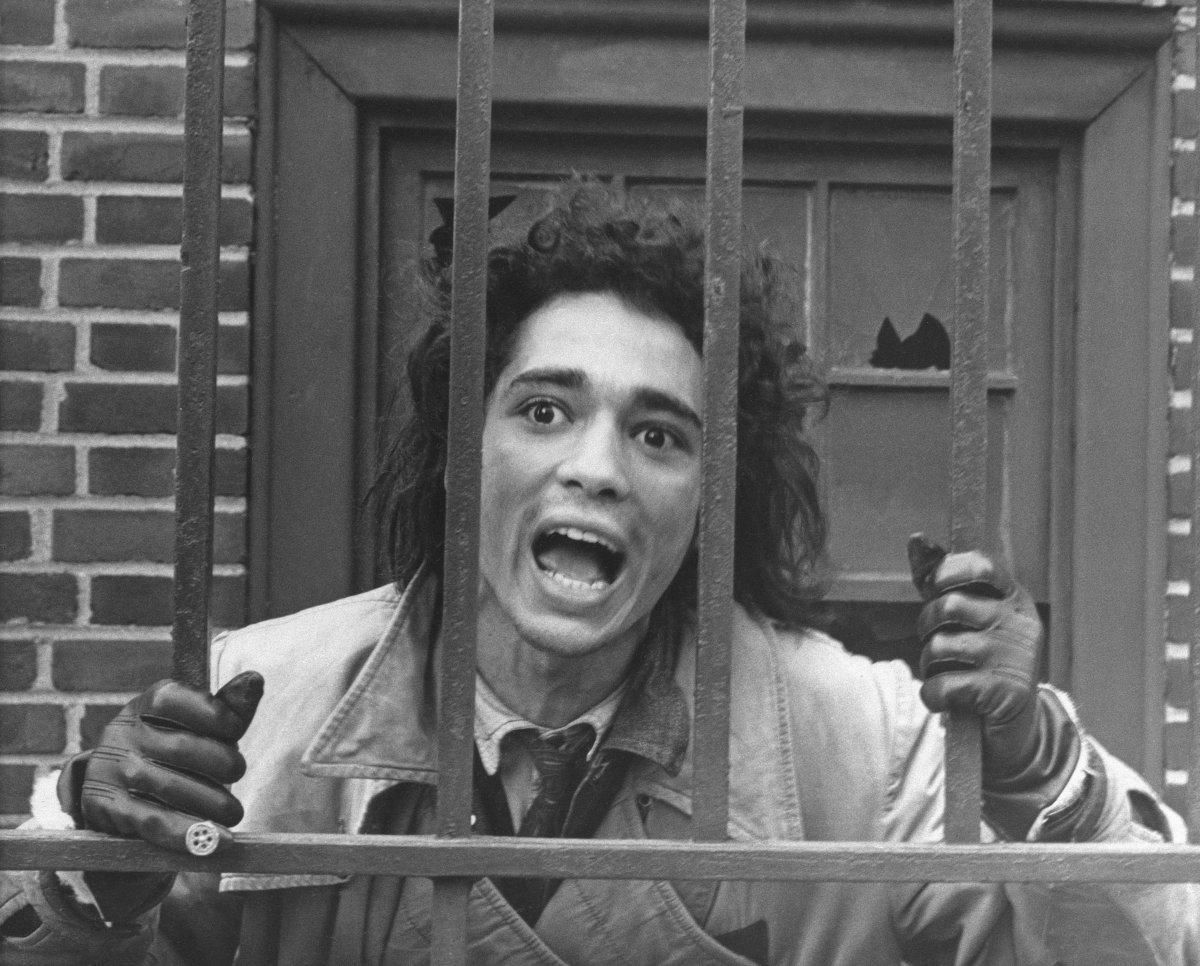

Groovy

Groovy

"I met Groovy in New Orleans," Galahad reminisced. "It was just about Mardi Gras time last February. We've been together ever since. Before that, I had always traveled alone. But there was something about Groovy that set him apart from everyone. People thought he was my satellite, but they were wrong. Groovy did his own thing and he had his own importance. There wasn't anything he wouldn't do: the weird, the unusual, the freaky, but it was beautiful. It made people laugh. Basically, we were in the same bag."

"For example," he went on, "recently, when we were coming back from San Francisco, we passed through Chicago. We decided to lay over a few days and look up some friends. Right away, we got busted for loitering. A cop started shaking down Groovy, who had an electric razor in his pocket. When the cop hit the razor case, Groovy screamed, 'Don't touch. It will go off and blow us all up.' Scared the cop stepped back. I thought, 'Here is a totally funny man, a guy who can freak-out a cop in the line of duty.'"

"To know Groovy for five minutes was to love him," said Galahad. "The tragic thing about his death -- its violence -- is that Groovy never lifted his hand to another man. I know, I traveled thousands of miles with him, and you can take my word that he would never have hurt a living thing. Even at the Be-In," Galahad attested, "I saw no hostility in Groovy, no belligerence toward the cops or the straight people. He didn't harass anyone. He seemed somehow to have got rid of his aggressions."

"Groovy freaked out in such a beautiful way," Galahad continued. "He would walk up to you an give you a pop bottle cap. If you asked him what it was for, he'd say, 'It's yours because I gave it to you.' It didn't have to be a thing of value. It didn't even have to mean anything to anyone. It was just the idea that he'd given you something."

"It's true," conceded Galahad, "Groovy took a lot of drugs. He turned on with everybody. And when he had the stuff, he turned other people on. He wasn't afraid to take anything; in fact, he took everything. He'd trip on acid, race with methedrine, smoke pot...It was a series of different trips. Yet, every time you'd see Groovy, he always wore the same smile and did the same crazy routines -- no, not the same, different ones. That was the beautiful thing about him. Groovy could make something out of nothing and make it the funniest thing you ever saw."

According to Galahad, Groovy was illiterate. He couldn't read or write and he didn't think it was necessary to learn. Galahad was his scribe. Often they would sit in the Peace Eye Bookstore together, Groovy dictating, Galahad writing. "He didn't have to write it," said Galahad, "he had many intelligent things to say, and what he said, came from the heart. His knowledge was gained through experience."

Last May, Galahad and Groovy were arrested for "impairing the morals of a minor," a 15-year-old run-away girl whom they had let stay in their apartment, called a commune. The charges against Groovy were dismissed. But the commune bit was very much his and his "vibrations" sustained it until the "publicity and the plastics moved in."

Before he was killed, Groovy confided a dream to Galahad. He said he wanted to open a non-profit cafe called the Thing Shop, where everyone could do his thing -- whether or not he had the price of a meal. Now, Groovy's friends are talking about having a wake for him. This, says Galahad, is all wrong. "He wouldn't want people to sit around in mourning or to walk the streets in paranoia. He'd want them to keep on doing their thing." A groovy memorial would be to open a Thing Shop. It's next on Galahad's list.

The newspapers have sent teams of reporters to the East Village. They have visited the scene of the crime and filed their stories:

"A 26-year-old Black Nationalist ex-convict today was charged with the bludgeon slayings of two whites, a teenage socialite and a tattooed hippie, in the basement of an East Village tenement following what police called a 'wild acid party' Saturday night..."

The obituaries of Linda Rae Fitzpatrick, 18, and James Leroy Hutchinson ("Groovy"), 24, will run like that all over the country as a reminder to Americans that freaking-out in the land of the free and the home of the brave can be fatal.

"The published picture of Linda must have been taken in high school," said Galahad, a Digger who was Groovy's closest friend. "It's all wrong. Her hair was blonde and short. She was a happy-go-lucky character -- a really beautiful chick. In one sense she was serious -- almost conservative; in another she was really high on life. In this way she was like Groovy who grooved on life. He didn't really need drugs to keep him high."

Groovy

Groovy

"I met Groovy in New Orleans," Galahad reminisced. "It was just about Mardi Gras time last February. We've been together ever since. Before that, I had always traveled alone. But there was something about Groovy that set him apart from everyone. People thought he was my satellite, but they were wrong. Groovy did his own thing and he had his own importance. There wasn't anything he wouldn't do: the weird, the unusual, the freaky, but it was beautiful. It made people laugh. Basically, we were in the same bag."

"For example," he went on, "recently, when we were coming back from San Francisco, we passed through Chicago. We decided to lay over a few days and look up some friends. Right away, we got busted for loitering. A cop started shaking down Groovy, who had an electric razor in his pocket. When the cop hit the razor case, Groovy screamed, 'Don't touch. It will go off and blow us all up.' Scared the cop stepped back. I thought, 'Here is a totally funny man, a guy who can freak-out a cop in the line of duty.'"

"To know Groovy for five minutes was to love him," said Galahad. "The tragic thing about his death -- its violence -- is that Groovy never lifted his hand to another man. I know, I traveled thousands of miles with him, and you can take my word that he would never have hurt a living thing. Even at the Be-In," Galahad attested, "I saw no hostility in Groovy, no belligerence toward the cops or the straight people. He didn't harass anyone. He seemed somehow to have got rid of his aggressions."

"Groovy freaked out in such a beautiful way," Galahad continued. "He would walk up to you an give you a pop bottle cap. If you asked him what it was for, he'd say, 'It's yours because I gave it to you.' It didn't have to be a thing of value. It didn't even have to mean anything to anyone. It was just the idea that he'd given you something."

"It's true," conceded Galahad, "Groovy took a lot of drugs. He turned on with everybody. And when he had the stuff, he turned other people on. He wasn't afraid to take anything; in fact, he took everything. He'd trip on acid, race with methedrine, smoke pot...It was a series of different trips. Yet, every time you'd see Groovy, he always wore the same smile and did the same crazy routines -- no, not the same, different ones. That was the beautiful thing about him. Groovy could make something out of nothing and make it the funniest thing you ever saw."

According to Galahad, Groovy was illiterate. He couldn't read or write and he didn't think it was necessary to learn. Galahad was his scribe. Often they would sit in the Peace Eye Bookstore together, Groovy dictating, Galahad writing. "He didn't have to write it," said Galahad, "he had many intelligent things to say, and what he said, came from the heart. His knowledge was gained through experience."

Last May, Galahad and Groovy were arrested for "impairing the morals of a minor," a 15-year-old run-away girl whom they had let stay in their apartment, called a commune. The charges against Groovy were dismissed. But the commune bit was very much his and his "vibrations" sustained it until the "publicity and the plastics moved in."

Before he was killed, Groovy confided a dream to Galahad. He said he wanted to open a non-profit cafe called the Thing Shop, where everyone could do his thing -- whether or not he had the price of a meal. Now, Groovy's friends are talking about having a wake for him. This, says Galahad, is all wrong. "He wouldn't want people to sit around in mourning or to walk the streets in paranoia. He'd want them to keep on doing their thing." A groovy memorial would be to open a Thing Shop. It's next on Galahad's list.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement