Like many of the men who fought and survived World War II, Quentin Aanenson anguished about what he had done and wondered why he had lived when so many of his comrades had died.

But unlike many of America's World War II veterans, Aanenson, a fighter pilot who grew up in Luverne, Minn., put his recollections and feelings before the world as one of the principal participants in Ken Burns' powerful TV documentary "The War."

Aanenson, an elegant and articulate son of the Midwest in the film series, died of cancer on Sunday at his home in Bethesda, Md.

He was 87.

"Death and love" marked Aanenson's considerable contribution to Burns' exhaustive, seven-part PBS documentary, reported the Washington Post, on the September 2007 day that the film debuted.

He narrowly escaped death on more than one occasion, including once when his P-47 Thunderbolt's cockpit caught fire after the plane was hit. He crash-landed, suffering cracked ribs and a head injury, but was back in the air a few days later.

"On another mission, Aanenson caught a column of German soldiers along a roadside. Opening the Thunderbolt's eight .50-caliber guns, he saw bullets tear into the men with such force that their bodies went flying. When he returned to his base in Normandy, he was sickened by the experience.

Then, he tells Burns' cameras, 'I went out and did it again and again and again and again,'" reported the Washington Post.

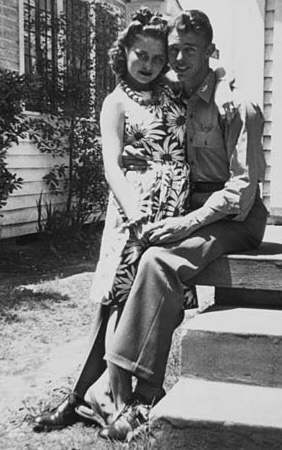

His hope, like so many combatants, was to return to loved ones, including his wife to be, Jackie Greer, who he met while training in Baton Rouge, La. She, too, played a prominent part in the Burns film.

In Burns' documentary, Aanenson, who flew 75 missions and was awarded a chestful of medals, narrated a letter that he wrote, but never sent, to Jackie. He had struggled to describe his experience after her questions about the war. The letter said, in part:

"I still doubt if you will be able to comprehend it. I don't think anyone can who has not been through it.

"I live in a world of death. I have watched my friends die in a variety of violent ways. ... Sometimes it's just an engine failure on takeoff resulting in a violent explosion. There's not enough left to bury. Other times, it's the deadly flak that tears into a plane. If the pilot is lucky, the flak kills him. But usually he isn't, and he burns to death as his plane spins in.

"So far, I have done my duty in this war. ... I have lived for my dreams for the future. But like everything else around me, my dreams are dying, too.

"In spite of everything, I may live through this war and return to Baton Rouge. But I am not the same person you said goodbye to on May 3."

At the urging of his family, he set out in the 1990s to make a video to show his family what his war was like in the skies over Europe.

It was a kind of therapy to make the video, and he wanted his family to know the horrors of war.

His video became much more than a home movie.

The documentary made by Aanenson, his wife and other family members was first aired across the nation on PBS in 1994. After Ken Burns, the documentary filmmaker, saw the Aanenson production, it spurred him to include Luverne as one of the four cities in America that anchored "The War." And the decision to include Luverne led to Al MacIntosh, who was editor of the Rock County Herald newspaper during the war. His heartfelt columns from the homefront provided another perspective on the war.

Lori Ehde, editor of the Rock County Star Herald recalled Aanenson as articulate, and a person who "had a keen sense of awareness of his place in the world."

Before the war, Aanenson had attended the University of Minnesota. In 1948, he graduated from Louisiana State University.

He went to work for Mutual of New York insurance, and after working in New Orleans, New York and San Antonio, he moved to the Washington area in 1955. He rose to become an officer in the firm, responsible for the Middle Atlantic region.

He retired in 1987.

"He was so much more than this American hero. He was just a wonderful family man," said his son, Jerry, of Boyds, Md.

In addition to Jerry, he is survived by his wife of 63 years, Jackie, of Bethesda; daughters, Vickie Murphy, of Ellicott City, Md., Debi Pyers, of Schaumburg, Ill.; 10 grandchildren, a brother, Curtis, of Minnetonka, and a sister, Mavis Porter, of Rock Rapids, Iowa.

Services will be at 1 p.m. Sunday Jan 3, 2009 in St. Andrew's Methodist Church in Bethesda.

Burial will be in Arlington National Cemetery outside Washington at 3 p.m. Feb. 27.

From the the offical PBS website of "The War":

Quentin Aanenson, the 5th of 6 children, was born on April 21, 1921, on a 160 acre farm five miles from Luverne. His grandparents had come to America from Norway and both of his parents grew up speaking Norwegian at home. He graduated from high school in 1939 attended the University of Minnesota for two years. In the summer of 1941 he moved to Seattle, where he got a job at Boeing and attended the University of Washington and was there when Pearl Harbor was attacked.

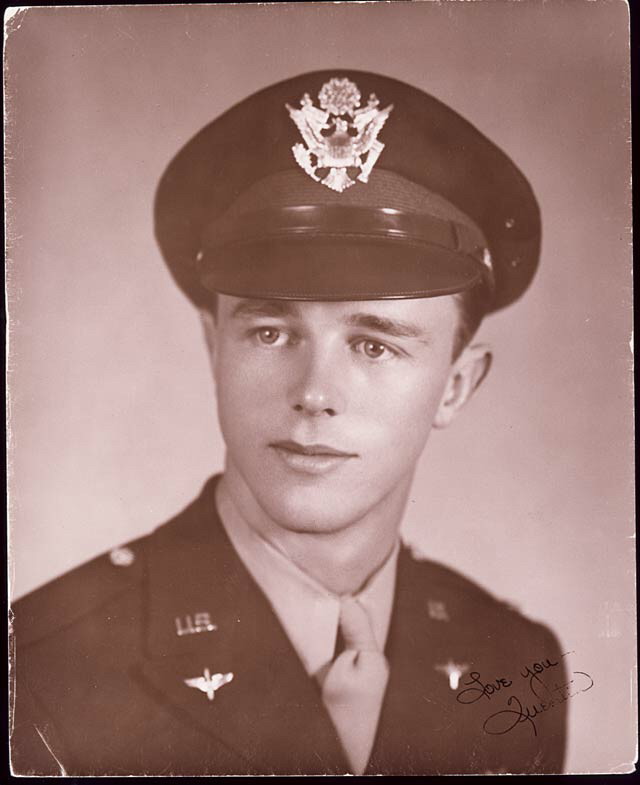

Although Aanenson hoped to become a pilot, colorblindness disqualified him -- until he took the eye test enough times to memorize it. He was accepted into the Army Air Corps in February 1943 and by early 1944 had graduated from flight school and been selected for fighter pilot training at Harding Field in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Two weeks after he got there, Aanenson met a local girl, Jacqueline Greer, at a dance. They began to date and quickly fell in love. They promised to write to each other every day while he was overseas, and she agreed not to date any other man more than three times. In mid-May of 1944 Aanenson arrived in England and in June was assigned to the 366th Fighter Group, 391st Fighter Squadron.

Aanenson's first combat mission was D-Day, June 6, 1944; he flew his P-47 Thunderbolt over the English Channel and dropped his bombs on German positions behind Pointe du Hoc in advance of the Allies' landing. On June 16th his squadron relocated to Normandy, and from there he flew bombing and strafing missions aimed at enemy troops and strong points. On July 25, 1944 Aanenson and his fighter group were among the 3,000 planes that bombed the German lines as part of Operation Cobra.

On August 3, 1944, on a mission over Vire, France, Aanenson's plane was hit

by flak and caught on fire. When he tried to bail out but couldn't, he put his plane into a steep dive, trying to crash as quickly as possible. The change in air pressure extinguished the cockpit fire, and Aanenson managed to fly back to his base and crash-land, suffering a concussion, dislocated shoulder, and burns. As soon as he recovered, he was back in the air again. November 17, 1944 was one of the most devastating days for Aanenson and his squadron. They flew in low under the clouds in order to attack German artillery and tanks just behind the front lines. German anti-aircraft gunners hit most of the 12 planes in his squadron. Aanenson's own plane was hit twice. Two of his three tent mates were killed.

By mid-December 1944, Aanenson had been in intense combat for almost six months. He had been caught in three cockpit fires; his planes were hit by flak on 20 missions; he had to crash land his plane twice; once his plane was hit by an 88mm cannon shell and nearly destroyed. (Aanenson's fighter group - consisting of 125 pilots at any given time - would lose 90 pilots over the course of the European war.)

When the Battle of the Bulge began, Aanenson was stationed in Belgium, and he was given a new assignment coordinating the close air support in front of the VII Corps. For 36 hours during the Bulge, he and his radio man were trapped behind enemy lines in the Ardennes.

In early 1945, Aanenson was promoted to captain, and in March was given a leave to go home. He went straight to Louisiana to see Jackie Greer and they were married three weeks later. When the war with Japan ended Aanenson was still in the United States, stationed in Atlantic City. After his discharge, he and Jackie moved to Baton Rouge, where he attended Louisiana State University and then embarked upon a successful career in the insurance business. He and Jackie have three children and eight grandchildren.

Like many of the men who fought and survived World War II, Quentin Aanenson anguished about what he had done and wondered why he had lived when so many of his comrades had died.

But unlike many of America's World War II veterans, Aanenson, a fighter pilot who grew up in Luverne, Minn., put his recollections and feelings before the world as one of the principal participants in Ken Burns' powerful TV documentary "The War."

Aanenson, an elegant and articulate son of the Midwest in the film series, died of cancer on Sunday at his home in Bethesda, Md.

He was 87.

"Death and love" marked Aanenson's considerable contribution to Burns' exhaustive, seven-part PBS documentary, reported the Washington Post, on the September 2007 day that the film debuted.

He narrowly escaped death on more than one occasion, including once when his P-47 Thunderbolt's cockpit caught fire after the plane was hit. He crash-landed, suffering cracked ribs and a head injury, but was back in the air a few days later.

"On another mission, Aanenson caught a column of German soldiers along a roadside. Opening the Thunderbolt's eight .50-caliber guns, he saw bullets tear into the men with such force that their bodies went flying. When he returned to his base in Normandy, he was sickened by the experience.

Then, he tells Burns' cameras, 'I went out and did it again and again and again and again,'" reported the Washington Post.

His hope, like so many combatants, was to return to loved ones, including his wife to be, Jackie Greer, who he met while training in Baton Rouge, La. She, too, played a prominent part in the Burns film.

In Burns' documentary, Aanenson, who flew 75 missions and was awarded a chestful of medals, narrated a letter that he wrote, but never sent, to Jackie. He had struggled to describe his experience after her questions about the war. The letter said, in part:

"I still doubt if you will be able to comprehend it. I don't think anyone can who has not been through it.

"I live in a world of death. I have watched my friends die in a variety of violent ways. ... Sometimes it's just an engine failure on takeoff resulting in a violent explosion. There's not enough left to bury. Other times, it's the deadly flak that tears into a plane. If the pilot is lucky, the flak kills him. But usually he isn't, and he burns to death as his plane spins in.

"So far, I have done my duty in this war. ... I have lived for my dreams for the future. But like everything else around me, my dreams are dying, too.

"In spite of everything, I may live through this war and return to Baton Rouge. But I am not the same person you said goodbye to on May 3."

At the urging of his family, he set out in the 1990s to make a video to show his family what his war was like in the skies over Europe.

It was a kind of therapy to make the video, and he wanted his family to know the horrors of war.

His video became much more than a home movie.

The documentary made by Aanenson, his wife and other family members was first aired across the nation on PBS in 1994. After Ken Burns, the documentary filmmaker, saw the Aanenson production, it spurred him to include Luverne as one of the four cities in America that anchored "The War." And the decision to include Luverne led to Al MacIntosh, who was editor of the Rock County Herald newspaper during the war. His heartfelt columns from the homefront provided another perspective on the war.

Lori Ehde, editor of the Rock County Star Herald recalled Aanenson as articulate, and a person who "had a keen sense of awareness of his place in the world."

Before the war, Aanenson had attended the University of Minnesota. In 1948, he graduated from Louisiana State University.

He went to work for Mutual of New York insurance, and after working in New Orleans, New York and San Antonio, he moved to the Washington area in 1955. He rose to become an officer in the firm, responsible for the Middle Atlantic region.

He retired in 1987.

"He was so much more than this American hero. He was just a wonderful family man," said his son, Jerry, of Boyds, Md.

In addition to Jerry, he is survived by his wife of 63 years, Jackie, of Bethesda; daughters, Vickie Murphy, of Ellicott City, Md., Debi Pyers, of Schaumburg, Ill.; 10 grandchildren, a brother, Curtis, of Minnetonka, and a sister, Mavis Porter, of Rock Rapids, Iowa.

Services will be at 1 p.m. Sunday Jan 3, 2009 in St. Andrew's Methodist Church in Bethesda.

Burial will be in Arlington National Cemetery outside Washington at 3 p.m. Feb. 27.

From the the offical PBS website of "The War":

Quentin Aanenson, the 5th of 6 children, was born on April 21, 1921, on a 160 acre farm five miles from Luverne. His grandparents had come to America from Norway and both of his parents grew up speaking Norwegian at home. He graduated from high school in 1939 attended the University of Minnesota for two years. In the summer of 1941 he moved to Seattle, where he got a job at Boeing and attended the University of Washington and was there when Pearl Harbor was attacked.

Although Aanenson hoped to become a pilot, colorblindness disqualified him -- until he took the eye test enough times to memorize it. He was accepted into the Army Air Corps in February 1943 and by early 1944 had graduated from flight school and been selected for fighter pilot training at Harding Field in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Two weeks after he got there, Aanenson met a local girl, Jacqueline Greer, at a dance. They began to date and quickly fell in love. They promised to write to each other every day while he was overseas, and she agreed not to date any other man more than three times. In mid-May of 1944 Aanenson arrived in England and in June was assigned to the 366th Fighter Group, 391st Fighter Squadron.

Aanenson's first combat mission was D-Day, June 6, 1944; he flew his P-47 Thunderbolt over the English Channel and dropped his bombs on German positions behind Pointe du Hoc in advance of the Allies' landing. On June 16th his squadron relocated to Normandy, and from there he flew bombing and strafing missions aimed at enemy troops and strong points. On July 25, 1944 Aanenson and his fighter group were among the 3,000 planes that bombed the German lines as part of Operation Cobra.

On August 3, 1944, on a mission over Vire, France, Aanenson's plane was hit

by flak and caught on fire. When he tried to bail out but couldn't, he put his plane into a steep dive, trying to crash as quickly as possible. The change in air pressure extinguished the cockpit fire, and Aanenson managed to fly back to his base and crash-land, suffering a concussion, dislocated shoulder, and burns. As soon as he recovered, he was back in the air again. November 17, 1944 was one of the most devastating days for Aanenson and his squadron. They flew in low under the clouds in order to attack German artillery and tanks just behind the front lines. German anti-aircraft gunners hit most of the 12 planes in his squadron. Aanenson's own plane was hit twice. Two of his three tent mates were killed.

By mid-December 1944, Aanenson had been in intense combat for almost six months. He had been caught in three cockpit fires; his planes were hit by flak on 20 missions; he had to crash land his plane twice; once his plane was hit by an 88mm cannon shell and nearly destroyed. (Aanenson's fighter group - consisting of 125 pilots at any given time - would lose 90 pilots over the course of the European war.)

When the Battle of the Bulge began, Aanenson was stationed in Belgium, and he was given a new assignment coordinating the close air support in front of the VII Corps. For 36 hours during the Bulge, he and his radio man were trapped behind enemy lines in the Ardennes.

In early 1945, Aanenson was promoted to captain, and in March was given a leave to go home. He went straight to Louisiana to see Jackie Greer and they were married three weeks later. When the war with Japan ended Aanenson was still in the United States, stationed in Atlantic City. After his discharge, he and Jackie moved to Baton Rouge, where he attended Louisiana State University and then embarked upon a successful career in the insurance business. He and Jackie have three children and eight grandchildren.

Inscription

Captain

US Army Air Corps

World War II

Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC)

Purple Heart

Air Medal & 9 Oak Leaf Clusters