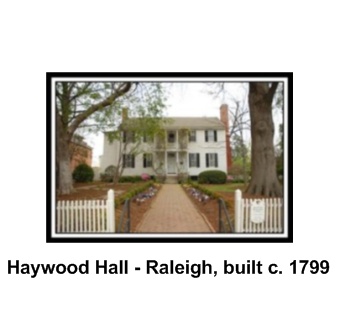

She was the paternal grandchild of Samuel Richardson Fowle of Woburn, MA who came to NC ca. 1820 and married Martha Barney Marsh of Washington, Beaufort Co, NC. She was the maternal grandchild of Dr. Julius Fabius Haywood & Martha Helen Whitaker of Raleigh and a direct descendant of State Treasurer John Haywood (1755-1827) who built "Haywood Hall" in Raleigh in 1799.

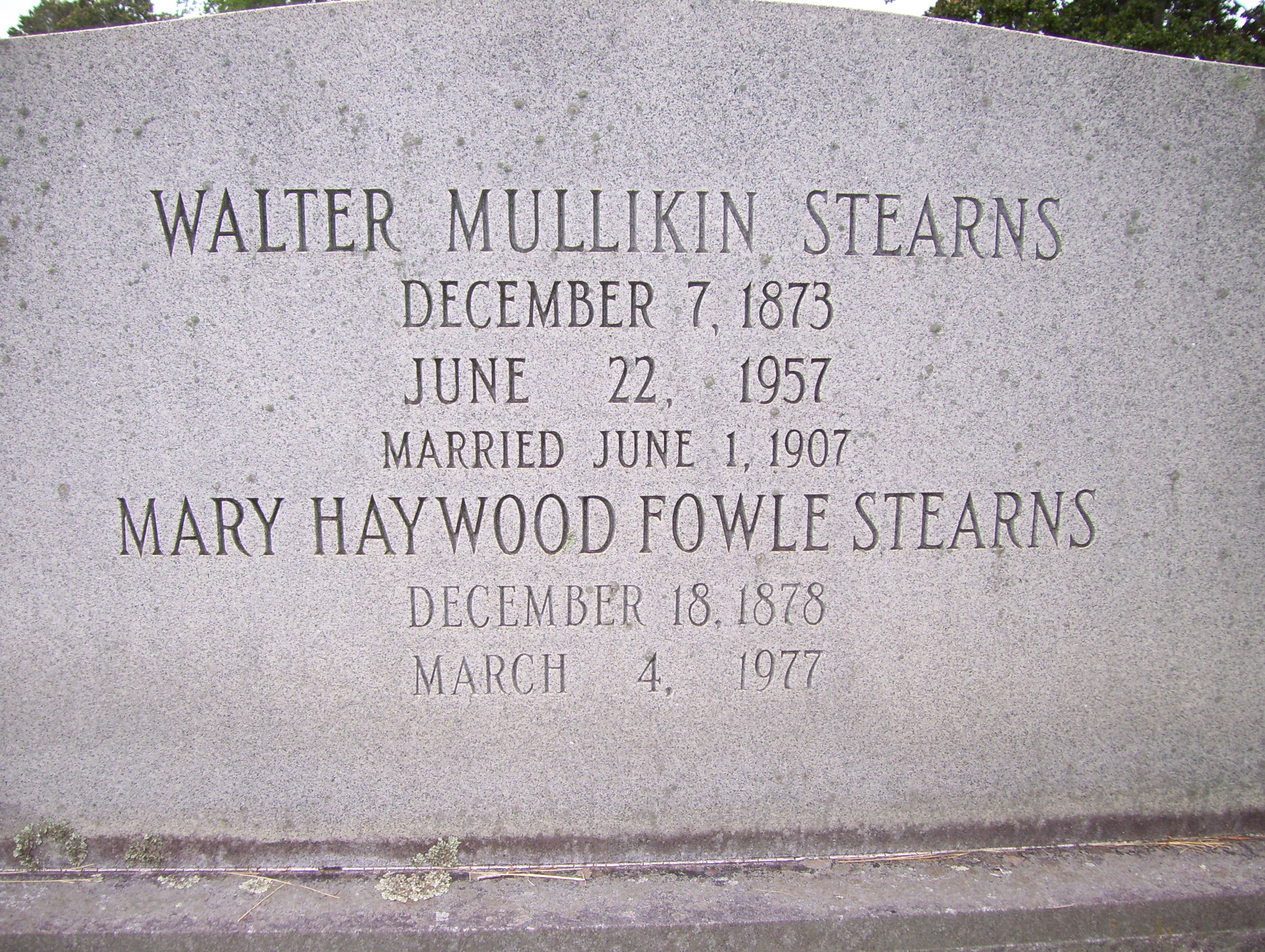

Mary was 30 years old in 1908 when she married Walter Mullikin Stearns, an electrical engineer from Waltham, MA. The couple first lived in Atlanta, then moved to Schenectedy, NY, where he worked for General Electric Corporation.

In January 1947, her husband was embroiled the trial of General Electric in New York City. Under indictment were GE Vice President Zay Jeffries, President W.G. Robbins of the Carboloy Co., and Walter M. Stearns, former GE trade manager and Gustav Krupp. Krupp was not present as he was being held in Germany for war crimes. Ironically during the trial Jeffries accused union leaders as having "un-American objectives" and denounced high wages.

Not the first time and not for the last, the giant General Electric Co. found itself in federal court on charges of violating anti-trust law. The U.S. government charged GE and a corporate ally with conspiracy to monopolize a market, raise prices and drive out competitors. But this was no ordinary anti-trust case. The year following the end of World War II, GE stood accused of criminal conspiracy with Krupp, a major German munitions firm. Their partnership artificially raised the cost of U.S. defense preparations while helping to subsidize Hitler's rearmament of Germany. The arrangement continued even after Nazi tanks smashed into Poland. GE was not alone among U.S. big business in having cordial, profitable arrangements with the corporations of Nazi Germany. Kodak, DuPont and Shell Oil are also known to have had business dealing with Germany. Due to a recent reparations case, the activities of General Motors and Ford are the most well known.

Throughout the trial General Electric's lawyers fought bitterly against the introduction of captured Nazi documents. In one such document Walter Stearns was quoted as telling the Germans that while GE intended to fix prices, "this must never be expressed in the contract itself or in any correspondence which might come into the files of GE."

The jury found that General Electric, its subsidiaries, and company officials were guilty on five counts of criminal conspiracy. Ironically, no further charges---such as sedition or hindering the war effort were leveled against the conspirators. Despite pleads from the Department of Justice for heavy sentences; Judge John C. Knox handed down only minor fines. Stearns and Jeffries were fined $2,500 each and Robbins $1,000. GE and Carboloy were fined $20,000 each and International General Electric only $10,000.

The fine for General Electric was particularly lax considering the firm had made millions on carboloy. In fact, in 1935 and 1936, General Electric's subsidiary that manufactured and sold carboloy made a profit of $694,000 in just those two years. The newspapers of the time failed to cover the trial and the convictions. Nevertheless, the newspapers found plenty of space on their front pages to cover General Electric's charges that UE members employed at atomic energy facilities were potential security risks. The union's UE News was the only paper to report on the trial and convictions. Once again the rich and powerful escaped from justice with a mere slap on the wrist.

Following the trial, the Stearns came to Raleigh where they moved into "Haywood Hall" when her uncle, Ernest Haywood, died in 1947. Ernest had actually left the property to his great nephew, who did not care to move to Raleigh. Thus, Mary Haywood Fowle Stearns, great granddaughter of John Haywood, purchased it. In 1947 she returned to Raleigh with her husband - moving into Haywood Hall and restoring the house and grounds. Mary and her husband Walter enclosed the west side of the porch, creating a kitchen within the house, and converted the old smokehouse

Mary Stearns had many cutting areas in the garden, along the brick paths and paths of stone. She planted Sweet Betseys, Acuba, and many Chrysanthemums, Zinnias, Marigolds, and Castor Bean plants. Her gardens were beautiful. She was so dedicated to them, it was not unusual to see her working in them at five o'clock in the morning!

Mary was widowed in 1957 when her husband of 49 years passed at age 84. The long marriage had been childless, and Mary remained alone in "Haywood House" tending her garden.

In her last nine years, Mary was an invalid. The bank overseeing her property during this period cut back much of the garden. Through the years, pine trees grew in various parts of the yard. By the late 1900s, pine trees were considered a country tree and were removed.

Mary Fowle Stearns died in 1977 at the advanced age of 99 years. She was buried in Oakwood near her husband.

Upon her death, Mary left the property to the National Society of Colonial Dames of America (NSCDA) in the State of North Carolina, and the house today operates as a Museum and Garden.

By the middle of the twentieth century, members of the NSCDA in many states were eager to preserve historic houses in their communities as examples of daily life in earlier times or as memorials to family members. In Minnesota, Kentucky, and North Carolina four houses owned by single women, all of whom were Colonial Dames and "the last of their lines," transferred their houses and almost all their contents to the organization. Mary Haywood Fowle Stearns gave Haywood Hall in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1977 "in memory of my father and mother ... and of her grandfather ... who built it" in 1799. It is the oldest house within the original city limits of Raleigh still on its original site, and the furnishings primarily reflect the tastes of the first two generations, augmented with additions by later family members, such as the painting bought by Mary and Walter Stearns while on holiday.

She was the paternal grandchild of Samuel Richardson Fowle of Woburn, MA who came to NC ca. 1820 and married Martha Barney Marsh of Washington, Beaufort Co, NC. She was the maternal grandchild of Dr. Julius Fabius Haywood & Martha Helen Whitaker of Raleigh and a direct descendant of State Treasurer John Haywood (1755-1827) who built "Haywood Hall" in Raleigh in 1799.

Mary was 30 years old in 1908 when she married Walter Mullikin Stearns, an electrical engineer from Waltham, MA. The couple first lived in Atlanta, then moved to Schenectedy, NY, where he worked for General Electric Corporation.

In January 1947, her husband was embroiled the trial of General Electric in New York City. Under indictment were GE Vice President Zay Jeffries, President W.G. Robbins of the Carboloy Co., and Walter M. Stearns, former GE trade manager and Gustav Krupp. Krupp was not present as he was being held in Germany for war crimes. Ironically during the trial Jeffries accused union leaders as having "un-American objectives" and denounced high wages.

Not the first time and not for the last, the giant General Electric Co. found itself in federal court on charges of violating anti-trust law. The U.S. government charged GE and a corporate ally with conspiracy to monopolize a market, raise prices and drive out competitors. But this was no ordinary anti-trust case. The year following the end of World War II, GE stood accused of criminal conspiracy with Krupp, a major German munitions firm. Their partnership artificially raised the cost of U.S. defense preparations while helping to subsidize Hitler's rearmament of Germany. The arrangement continued even after Nazi tanks smashed into Poland. GE was not alone among U.S. big business in having cordial, profitable arrangements with the corporations of Nazi Germany. Kodak, DuPont and Shell Oil are also known to have had business dealing with Germany. Due to a recent reparations case, the activities of General Motors and Ford are the most well known.

Throughout the trial General Electric's lawyers fought bitterly against the introduction of captured Nazi documents. In one such document Walter Stearns was quoted as telling the Germans that while GE intended to fix prices, "this must never be expressed in the contract itself or in any correspondence which might come into the files of GE."

The jury found that General Electric, its subsidiaries, and company officials were guilty on five counts of criminal conspiracy. Ironically, no further charges---such as sedition or hindering the war effort were leveled against the conspirators. Despite pleads from the Department of Justice for heavy sentences; Judge John C. Knox handed down only minor fines. Stearns and Jeffries were fined $2,500 each and Robbins $1,000. GE and Carboloy were fined $20,000 each and International General Electric only $10,000.

The fine for General Electric was particularly lax considering the firm had made millions on carboloy. In fact, in 1935 and 1936, General Electric's subsidiary that manufactured and sold carboloy made a profit of $694,000 in just those two years. The newspapers of the time failed to cover the trial and the convictions. Nevertheless, the newspapers found plenty of space on their front pages to cover General Electric's charges that UE members employed at atomic energy facilities were potential security risks. The union's UE News was the only paper to report on the trial and convictions. Once again the rich and powerful escaped from justice with a mere slap on the wrist.

Following the trial, the Stearns came to Raleigh where they moved into "Haywood Hall" when her uncle, Ernest Haywood, died in 1947. Ernest had actually left the property to his great nephew, who did not care to move to Raleigh. Thus, Mary Haywood Fowle Stearns, great granddaughter of John Haywood, purchased it. In 1947 she returned to Raleigh with her husband - moving into Haywood Hall and restoring the house and grounds. Mary and her husband Walter enclosed the west side of the porch, creating a kitchen within the house, and converted the old smokehouse

Mary Stearns had many cutting areas in the garden, along the brick paths and paths of stone. She planted Sweet Betseys, Acuba, and many Chrysanthemums, Zinnias, Marigolds, and Castor Bean plants. Her gardens were beautiful. She was so dedicated to them, it was not unusual to see her working in them at five o'clock in the morning!

Mary was widowed in 1957 when her husband of 49 years passed at age 84. The long marriage had been childless, and Mary remained alone in "Haywood House" tending her garden.

In her last nine years, Mary was an invalid. The bank overseeing her property during this period cut back much of the garden. Through the years, pine trees grew in various parts of the yard. By the late 1900s, pine trees were considered a country tree and were removed.

Mary Fowle Stearns died in 1977 at the advanced age of 99 years. She was buried in Oakwood near her husband.

Upon her death, Mary left the property to the National Society of Colonial Dames of America (NSCDA) in the State of North Carolina, and the house today operates as a Museum and Garden.

By the middle of the twentieth century, members of the NSCDA in many states were eager to preserve historic houses in their communities as examples of daily life in earlier times or as memorials to family members. In Minnesota, Kentucky, and North Carolina four houses owned by single women, all of whom were Colonial Dames and "the last of their lines," transferred their houses and almost all their contents to the organization. Mary Haywood Fowle Stearns gave Haywood Hall in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1977 "in memory of my father and mother ... and of her grandfather ... who built it" in 1799. It is the oldest house within the original city limits of Raleigh still on its original site, and the furnishings primarily reflect the tastes of the first two generations, augmented with additions by later family members, such as the painting bought by Mary and Walter Stearns while on holiday.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement