3/12/1861—11/2/1932

Albert Victor Ballin (not to be confused with the German shipping magnate), was a colorful character, prominent in the Deaf community, who had a promising early career as a portraitist, then became an actor in Hollywood shortly before the advent of the “talkies.” According to Deborah Meranski Sonnenstrahl’s Deaf Artists in America: Colonial to Contemporary, Albert Ballin was the son of a Deaf father, David Ballin, “a popular lithographer who operated an engraving business in New York and his son could often be found helping at the family business.” He was thus the first known Deaf artist in the U.S. who had a Deaf parent. He was born into a Jewish family, although it is unknown to what extent he identified as a Jew and maintained a connection to the Jewish community.

Deafened at age 3, Albert attended the New York Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb (now New York School for the Deaf, known as “Fanwood”). He studied with the Deaf artist Henry Humphrey Moore (1844-1926), a successful society portraitist and “Orientalist,” who encouraged Ballin to study and travel in Europe. He visited Paris, studied with Spanish painter José Villegas y Cordero (1848-1922), noted for his historical and Orientalist paintings and society portraits (the influence of Moore and Cordero can be seen in Ballin’s work), and spent three years in Rome.

One of his best-known portraits (1891) is that of Rev. Thomas Gallaudet, the eldest son of Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, co-founder of the American School for the deaf in Hartford. Rev. Gallaudet, who devoted his career to the Deaf community, founded the first Episcopal church for a Deaf congregation, St. Ann’s in Manhattan. In 1903, Ballin painted a portrait of Rev. Gallaudet’s youngest brother, Edward Miner, founder and first president of what is now Gallaudet University. Ballin portrayed Rev. Gallaudet, his friend, as a shrewd but kindly man; it’s a compelling depiction. He also did miniatures on ivory; his work was noted for its delicacy and insight.

Ballin married Mattie B. Whelan in 1893. They had met in Buffalo while he was campaigning for Grover Cleveland. (He later switched his allegiance to McKinley.) She was hearing, but a skilled signer. They first settled in New York City, where Ballin maintained active involvement in Deaf Community social affairs; he was a member of the Fanwood Quad Club, a men’s club founded by faculty and students of the printing department of New York School. He was also a fine chess player, and participated in live competitions and conducted correspondence matches with other Deaf chess buffs.

Around 1897, Albert and Mattie moved to Pearl River, a village on the southern New York border, but a short distance northwest of Manhattan. They had two daughters, Marion and Viola, both hearing, both skilled native

signers.

In 1924, Ballin relocated to Hollywood (traveling by steamer through the Panama Canal). He and Mattie were evidently separated by that time; we don’t know if he ever saw his daughters again, or if he maintained contact with them. Bringing with him a script for a historical epic he hoped to get produced, he embarked on an acting career, hoping to become a leading actor. He met some of the great producers and several actors, and made friends with a few; he even taught them how to sign.

He had a bit of success in silent films, debuting as a shaggy and wise hermit in His Busy Hour (1926), an innovative silent comedy with an all-Deaf but nonsigning cast who used pantomime and expressions, with title cards. (Never distributed and long believed lost, it was rediscovered by film historian John S. Schuchman and screened at the first DEAF WAY International Conference and Festival in 1989.) Mostly, though, he played extras—when he could find the work. (He’s recognizable in a handful of these movies.) He had made some useful contacts, including patrons who commissioned him to do portraits. One such portrait was that of Thomasina Mix, the 3-year-old daughter of Western star Tom Mix. The advent of the talkies effectively put an end to his acting ambitions, and the onset of the Great Depression meant a virtual end to the demand for his art.

Nowadays, Ballin is remembered for his provocative (partially fictional) memoir/essay, The Deaf Mute Howls. Although critical of schools for the deaf, and friendly with Alexander Graham Bell, he was a staunch advocate of sign language, which he considered the universal language. Largely ignored when it was published in 1930, Ballin’s memoir is now considered a classic, and was recently reprinted by Gallaudet University Press. The Deaf actor Bruce Hlibok performed a one-man show, The Deaf-Mute Howls, based on the book, which audiences found provocative and disturbing. Ballin would likely have been pleased.

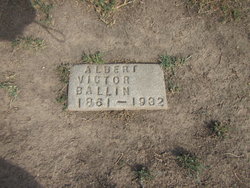

He died in 1932 of a heart ailment, age 77, and is interred, alone, in the Home of Peace Memorial Park, a Jewish cemetery, with only a stark grave marker, no inscribed stone. Virtually forgotten after his death, he has been rediscovered and celebrated as a character whose life was more colorful and stranger than any fiction.

—Linda Levitan

3/12/1861—11/2/1932

Albert Victor Ballin (not to be confused with the German shipping magnate), was a colorful character, prominent in the Deaf community, who had a promising early career as a portraitist, then became an actor in Hollywood shortly before the advent of the “talkies.” According to Deborah Meranski Sonnenstrahl’s Deaf Artists in America: Colonial to Contemporary, Albert Ballin was the son of a Deaf father, David Ballin, “a popular lithographer who operated an engraving business in New York and his son could often be found helping at the family business.” He was thus the first known Deaf artist in the U.S. who had a Deaf parent. He was born into a Jewish family, although it is unknown to what extent he identified as a Jew and maintained a connection to the Jewish community.

Deafened at age 3, Albert attended the New York Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb (now New York School for the Deaf, known as “Fanwood”). He studied with the Deaf artist Henry Humphrey Moore (1844-1926), a successful society portraitist and “Orientalist,” who encouraged Ballin to study and travel in Europe. He visited Paris, studied with Spanish painter José Villegas y Cordero (1848-1922), noted for his historical and Orientalist paintings and society portraits (the influence of Moore and Cordero can be seen in Ballin’s work), and spent three years in Rome.

One of his best-known portraits (1891) is that of Rev. Thomas Gallaudet, the eldest son of Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, co-founder of the American School for the deaf in Hartford. Rev. Gallaudet, who devoted his career to the Deaf community, founded the first Episcopal church for a Deaf congregation, St. Ann’s in Manhattan. In 1903, Ballin painted a portrait of Rev. Gallaudet’s youngest brother, Edward Miner, founder and first president of what is now Gallaudet University. Ballin portrayed Rev. Gallaudet, his friend, as a shrewd but kindly man; it’s a compelling depiction. He also did miniatures on ivory; his work was noted for its delicacy and insight.

Ballin married Mattie B. Whelan in 1893. They had met in Buffalo while he was campaigning for Grover Cleveland. (He later switched his allegiance to McKinley.) She was hearing, but a skilled signer. They first settled in New York City, where Ballin maintained active involvement in Deaf Community social affairs; he was a member of the Fanwood Quad Club, a men’s club founded by faculty and students of the printing department of New York School. He was also a fine chess player, and participated in live competitions and conducted correspondence matches with other Deaf chess buffs.

Around 1897, Albert and Mattie moved to Pearl River, a village on the southern New York border, but a short distance northwest of Manhattan. They had two daughters, Marion and Viola, both hearing, both skilled native

signers.

In 1924, Ballin relocated to Hollywood (traveling by steamer through the Panama Canal). He and Mattie were evidently separated by that time; we don’t know if he ever saw his daughters again, or if he maintained contact with them. Bringing with him a script for a historical epic he hoped to get produced, he embarked on an acting career, hoping to become a leading actor. He met some of the great producers and several actors, and made friends with a few; he even taught them how to sign.

He had a bit of success in silent films, debuting as a shaggy and wise hermit in His Busy Hour (1926), an innovative silent comedy with an all-Deaf but nonsigning cast who used pantomime and expressions, with title cards. (Never distributed and long believed lost, it was rediscovered by film historian John S. Schuchman and screened at the first DEAF WAY International Conference and Festival in 1989.) Mostly, though, he played extras—when he could find the work. (He’s recognizable in a handful of these movies.) He had made some useful contacts, including patrons who commissioned him to do portraits. One such portrait was that of Thomasina Mix, the 3-year-old daughter of Western star Tom Mix. The advent of the talkies effectively put an end to his acting ambitions, and the onset of the Great Depression meant a virtual end to the demand for his art.

Nowadays, Ballin is remembered for his provocative (partially fictional) memoir/essay, The Deaf Mute Howls. Although critical of schools for the deaf, and friendly with Alexander Graham Bell, he was a staunch advocate of sign language, which he considered the universal language. Largely ignored when it was published in 1930, Ballin’s memoir is now considered a classic, and was recently reprinted by Gallaudet University Press. The Deaf actor Bruce Hlibok performed a one-man show, The Deaf-Mute Howls, based on the book, which audiences found provocative and disturbing. Ballin would likely have been pleased.

He died in 1932 of a heart ailment, age 77, and is interred, alone, in the Home of Peace Memorial Park, a Jewish cemetery, with only a stark grave marker, no inscribed stone. Virtually forgotten after his death, he has been rediscovered and celebrated as a character whose life was more colorful and stranger than any fiction.

—Linda Levitan

Inscription

Very Simple Grave Marker - see photo

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement