My Mother, Bridget Quinlan, was born in the village of Ross Crea, not far from the City of Limeric, Ireland. She came to Montreal, Canada with an older sister and her husband, in the year 1847. On Christmas day 1849, she was married to my Father, a young man about twenty years of age. They made their home in Montreal where my Father was a tutor in wealthy families. About 1850 they moved with my Mother's relatives to Wisconsin, as the U.S. government was giving large farms to settlers. My Mother's first child - a boy - was born on a prairie in Wisconsin. The Indians used to come to the rude cabin to look at the little white child, much to my poor Mother's discomfort, for these Indians were dressed in robes of skins and wore moccasins on their feet. A second child, another boy named Thomas Weston Macaulay, was born there also. He lived to a good old age and died in San Francisco in 1929.

About 1851, the Gold excitement reached the people in the east. Upon hearing this my Father gave up farming, for which he was totally unfitted, and prepared to leave at once for the land of Gold (California). My poor Mother was broken hearted as she worshipped my Father and it might be for years, or maybe forever, before she would see him again. It was an easy matter to sell the farm on Dell Prairie, Wisconsin for a large sum: And, it was enough to take my Father on the long journey to California, and to provide for my Mother and her two children for a year or more. As soon as Father was gone, my Mother moved into her sister's family and continued to live there, in Portage City, for seven years. Her first son died when he was four years old.

My Mother received a letter and some money for her to go out to California. So, she began to get ready for the long trip. My brother, Thomas, was then eight years old. They left Portage City and went to New York, and then by water to the Isthmus of Panama. It was a tempestuous voyage, but nothing to what lay ahead of her. I do not remember her telling me about crossing the Isthmus, but she and my brother were put aboard a steamer which finally reached San Francisco. She received a letter there from my Father telling her to cross the San Francisco Bay and take a train to Sacramento. This was a terrible shock to my Mother as she expected, after her long sea voyage, to see my Father in San Francisco.

Once in Sacramento, the train terminus, she was introduced to a new kind of transportation. Early the next morning she was awakened by a gruff voice saying, "Hurry and dress as the mule train is all saddled and ready to start." She and brother ate a hurried breakfast and were ready. My poor Mother was shocked when a man approached her and said, "Now, lady, I'll help you up into the saddle. This mule is very gentle and used to carrying women, but you are the only lady passenger today. I have a nice little curly mule for the boy to ride." Of course, my brother was delighted. My Mother had never been on a horse and she had never heard of a mule. It was a long train, the passengers all men, going to the various 'gold diggins'. My Mother had to be lifted off of the mule whenever they reached the stopping place at the close of the day. Mother told me that if it had not been for my brother, she could have gone no further. But, finally, after traveling for over a week, over mountains, rough, trails and hazardous canyons, she reached her destination at a little place by the name of "Callahan's Ranch". There was a good hotel in this flourishing mining camp. Located in the heart of the Siskiyou Mountains about seventy miles west and south of Yreka. But my Father was not there to meet them. My Father's partner was there, and he took them over a rough trail about five miles to her final home---a rude log cabin in a great forest. Father came out to meet them. Mother hardly knew him; the past seven years had changed him greatly. The only thing that seemed to cheer my Mother was a huge fireplace, and on the hearth there was a big pot of pork and beans. She was so tired and so hungry that I guess she thought more about eating than anything else. My Mother did not tell me any of the details that took place upon her arrival at the cabin, or anything more until in the course of two years I was born, March 6th, 1861. My dear Mother was all alone, no doctor or nurse. She sent my brother to the village three miles away for help. A neighbor there came at once and did everything she could. I relate this to show what the pioneer women often had to endure.

One dark night when I was sleeping in my wooden cradle, Mother and my brother heard some crying and unearthly yells not far from our cabin. With the dim light of a lantern they went out to offer help. The noise ceased, but very close to them they saw two gleaming eyes, then a fierce growl. It was a cougar, often called a California Mountain Lion. My Mother often told me of another happening that gave her a great fright. A band of Indians had camped near by. There seemed to be two factions. They were fighting and 'pow-wowing'. There were several ponies tied to the trees. Presently, they dragged a young Indian girl over and threw her onto a pony. Several Indians mounted the ponies and rode away toward the high mountains. The Indians that were left in the camp started a war dance with dismal yells and pow-wows. By night they, like the Arabs, folded their tents and silently slipped away.

My brother, Thomas, never did go to school as there were no schools within walking distance. Mother and Father taught him to read and write. In the winter, when there was enough water for mining, he worked with my Father; and in the summer he cut cordwood to be sold. My Father was a hard master and expected by brother to work like a man. When he was fifteen he ran away and worked in a mine about forty miles from our place. Once a year he came back to see Mother and me.

MARCH 31, 1938

Tom always had his gun with him and would bring a fine grouse for Mother to cook. Mother worried and grieved all those years about Thomas.

On one occasion when he came home, it was after dark and I ran to meet him. He stooped down to kiss me. My little dress caught in the trigger of his gun; and, fortunately, as it was resting on the ground upright, the shot went up, just mis¬sing my head. From that day, I have been afraid of firearms of every kind.

Two years after I was born, we moved farther down the creek, rightly named "Wild Cat". This was a large well-built cabin. Here my only sister, Margret Ann, was born, September 6, 1863. She had a hard life before her, full of sorrow and disappointment. Her husband, T. J. Ankeny, died several years before her; and her only child, Miss Pauline Ankeny, is now a teacher in the public schools of Los Angeles. My sister died in March 1937.

When Maggie and I were little children, we moved again, about two miles farther down the creek. My Father settled upon a nice piece of land among the hills and built a small house of lumber--no more log cabins. Mother was well pleased, and Father located a good paying gold mine within walking distance of the house, where sister and I grew up. We attended the public school at 'South Fork', nearly three miles away, walking over a mountain trail. I forgot to mention that my Mother took the County School Exam for school teachers and passed creditably. She was educated in a convent in Ireland. My Mother was engaged to teach the first public school in that part of the county which was in the mining camp on East Fork. She had to move into another log cabin, as it was impossible to walk back and forth night and morning. I remember well sitting in the foot of the cradle with sister Mag, a little babe asleep in the other end, while Mother was teaching. When this school was finished, she continued to live on "Macauley Ranch" the rest of her life. My sister and her husband came to live with Mother and Father in 1894. Mother and Father were growing old, and Mag and Frank took care of them until both of them had passed away. My Father died in 1892; my Mother in 1909.

I was about 14 years old when I went to live with a friend of Mother's who lived at Callahan. There were three children in the family. The head of the family was away most of the time. He drove a six-mule team to Redding, the terminus of the R.R., and returned with a huge wagonload of freight for Callahan and Etna. The trip took about a month, Mrs. Blevins, Mother's friend, was a kind woman and took good care of her children and home. She taught me many useful things - to sew on a machine, to cook and help with the family washing and ironing (no small item). There were no such things as washing machines in those days. I worked hard but went home every Sunday to see Mother and sister. I stayed with Mrs. Blevins seven months. Then I went home to live and go to school in Callahan.

I had nearly three miles to walk back and forth to school. The next year when school closed, I heard of another position, much farther away. But I was to teach the children and reserve $20.00 per month. This place was a large hotel or summer resort, near the town of Trinity Center in Trinity County. I had to travel in a big overland, four-horse stagecoach which, of course, was all new to me. Leaving Callahan in the evening, we rode all night over a rough mountain road, the horses going at a quick trot. I was thrown from side to side in the stage until I was so bruised and sick I could hardly get out when I reached the hotel.

The next day my duty as teacher for the children began. There were four boys and a little girl. The boys were unruly; and when they saw a girl of 15, not much older than themselves, they did about as they pleased. I soon was told there were many things I could do besides teach. Anyway, I learned to be a waitress, a chambermaid, a laundress; and when there was nothing else to do, I could close the toll gate in front of the hotel and let no team pass until I collected the money. I stayed in this place a year. After being there two or three months, another girl was brought to teach the little girl music. A fine new square piano was placed in the parlor, the first piano I had ever seen. The music teacher came from San Francisco and was a fine musician, and also my own age - 15. We soon became chums. I took an occasional music lesson from her, and she said I learned rapidly.

APRIL 4, 1938

After the little music teacher left for San Francisco, I continued to live at the Summer Resort until I had been there a year. Then it dawned upon me that I was growing up without an education - the thing I had always desired. So, I boarded the old stagecoach and finally arrived at Callahan. I went into the hotel to rest, and the proprietor and his wife, who had known me all my life, said they needed help badly and would pay me $15.00 a month. I agreed, but first went home - three miles - to visit my Mother and sister before I began to work at the Callahan Hotel. They were very kind to me and let me practice on their new piano whenever I had time. I went there in the fall, and after being there several months, Mrs. Hayden said she wanted to take a trip to Yreka, the County seat, and 40 miles north of Callahan. I was delighted when she planned to take me along. She knew I wanted to attend school, and as she knew several good families there, said she would find me a place where I could work for my room and board and go to school. I entered the High School, as I had finished grammar school two years previous in South Fork and Callahan. I was now 17 years old. When I was 19 I graduated from High School soon after I took the Teacher's Exam and passed receiving a primary County Certificate. Then a school was offered to me 40 miles away, north of Yreka near the Klamath River. The people I boarded with were rather old people and had a good ranch with oceans of cream, milk and butter. Also, a fine orchard with an abundance of fruit. The schoolhouse was four miles from my boarding place. So, I bought a horse, a dear little gentle animal, and named her Lady Jane. My pupils were mostly Indian children and several halfbreeds. They were good children, easy to manage.

About this time I met a dear girl, Ella Sheppard, another schoolmarm who taught not many miles away, over in the State of Oregon. She too had a pony and used to ride down to my school quite often. She wanted to organize a Sunday School for the children. She used to illustrate the lessons on the blackboard with colored crayon, and the children seemed to understand as more of them attended. Her pupils were mostly Indians, as she could speak the Chinook language. She and I used to have such good times in the glorious, picturesque country. The mighty Klamath River, deep and swift, was only a few feet from my schoolhouse. Near the river bank were high cliffs of rock that no one tried to climb. Ella and I would ride for miles up the river until it was time for her to come back and catch the ferry that would take her back to the Oregon side. In the autumn, our schools closed, and I said farewell to Ella. What a dear, vivacious girl she was. I wonder where she is now!

Soon after school closed, until the next spring, I returned to Yreka. There I secured a nice room and stayed for a time. I visited my brother and his family who lived over the mountains a few miles away. I returned to Yreka in the spring. I heard they wanted a teacher in the place where I first went to school, South Fork. They gave it to me, and I lived at home with Father and Mother. Maggie had gone out to work in families in the neighborhood. I had only a few pupils here, some of them almost my own age. My parents were so happy to have me home with them, and the money I usually paid for board was a help also. When this school closed in the fall, I heard of a winter school over at Mt. Shasta, about 60 miles away. This was a community of well-to-do ranchers. They had fine horses and carriages and large herds of cattle. I boarded with a nice family where there were young people, and I had only a short distance to walk to school. This was fortunate as it was a winter school and very deep snows fell there being so close to Mt. Shasta. I did not have many pupils, and they were very nice young people. I used to go horseback riding with three or four others right up to the side of the great mountain. There were dances in the town of Sisson, not far away, and I often think of the gay life I had when I lived there. My school closed in the spring and so I planned to go "down below", as everyone said, and attend the State Normal School in San Jose. I received $75.00 per month for nine months of school. California always paid its teachers well. I went back to Callahan to see my parents, then to Yreka, where I was met by a girl I knew who was going to go to the Normal School also. We boarded the big four-horse overland stage at Yreka and were off. It was a hard journey, two days and a night before we reached the terminus of the R.R. at Redding, California. This was my first sight of a train and locomotive. I was just 21 then. I'll admit it frightened me and filled me with wonder. I could not imagine why a locomotive should make such an awful noise. When we entered the passenger coach, I was bewildered. The conductor in uniform punching tickets and putting little slips of paper in men's hats. We left early in the morning and reached the great city of San Francisco at night. How amazed we were at the bright lights, though that was a long time before the invention of electric lights. We went to a hotel. The next day a friend to whom we had written took us on the street cars for a tour of the beautiful city.

The next day our friend took us across in the ferry to Oakland where we took the train to San Jose. This was through the most beautiful gardens and parks I had ever seen. In a few hours we reached San Jose - a very pretty city. We could see the Normal School and were amazed at its size. That afternoon we secured a room with other students near the school.

The next morning, we went to enroll. We waited a long time in a big office. Finally, a gentleman entered and questioned us very thoroughly. At last he said I could enter as a high Junior, as I had taught two years: I finished my junior year, but as my funds were getting low, I had to go back to Siskiyou and get a school again. I cannot remember now where I taught, but the trustees wanted me to return for the next term. Another teacher and I went back to Yreka for the winter. We planned to study for 1st grade certificates, but something prevented us from doing so. We secured a very nice room in an ex-Judge's family. He'd passed away but a short time before! His widow was a dear, kind person, not much older than we were, though she had three or four young children. I do not know how the poor woman existed as the neighbors told us the Judge had left very little besides the home. But she did not charge us very much for the nice room. However, one day I read a letter from an old

friend of mine that I used to know when I worked at Callahan. He was a telegraph operator then as well as a lineman. The two jobs went together in those days. He was an exceedingly witty fellow and very well educated, also very good look¬ing except that he had but one eye. That didn't seem to bother him, though. He had many friends. Everyone liked him. But I must get back to the letter he wrote me from away down in San Luis Obispo County. He was married now and had a very beautiful wife, though she was a cripple who used to walk with a cane. Anyway, Tobe wanted me to come down at once and take a very good school with only a few pupils. They were looking for a teacher everywhere and could not find one. The salary was $65.00 per month. It did not take me long to decide, as I was getting awful tired of Yreka and Siskiyou. However, I went back to Callahan to tell my Mother and Father goodbye. I took the overland stage from there to Redding, California. There I took the train to Salinas in Southern California. That was the most terrible trip I ever had in my life!! But I finally arrived in Salinas after a terrible, bumpy ride in that R.R. coach. All day it was rain¬ing very hard, and I was hurried into a stagecoach, and we were off again. Another day and night of being bumped off one seat and onto another, occasionally hitting my head against the cover of the coach. Another lady passenger was with me. It was her first experience with anything of this kind and she moaned and wept and cursed the day she ever heard of San Luis Obispo. When morning broke and the green hills were on all sides with the warm sunshine, one almost forgot the miseries of the night. But it wasn't so beautiful after all. We were at the brink of a great rolling, muddy river with no bridge in sight. The stage driver began unhitching the horses and preparing for the trip back. Away on the far bank of the river we saw a man in a rowboat trying to come for us. He finally got to our side and the boat struck bottom. He told me to come as close to him as possible and jump on his back and he would put me in the boat. He did likewise with the other poor woman, though she was sobbing all the time. She put her arms around his neck and he took hold of her legs and finally dumped her in the boat. He had a hard time rowing us across as the great waves of sand were hard to pull against. There was a stage waiting for us on the other side and the driver helped to get us out of the boat onto dry land. We rode along the banks of the mighty Salinas River for a few miles. It was a beautiful sunny morning, the bright green hills and valleys made me glad I had come to Southern California after all the hardships. By noon we had reached my destination - Mission San Miguel. All that was to be seen at first was the old mission. It was in a pretty good state of preservation then -nearly 50 years ago. A little farther on we came to what was to be my home for nine months. My fellow passenger stayed in the stage another days' journey onto the city of San Luis Obispo. I never saw her again. The stage drove up to the hotel porch and there stood my friend, Tobe, all smiles to welcome me. This hotel was a one-story frame building with a big front erected from the top of the porch, and the whole building was whitewashed. There were three or four windows and two doors. One of these doors was the barroom for men only. A lot of saddle horses were hitched out front with Mexican saddles, lariats, and jingling spurs hung on the sides of the saddles. It was just dinner time when I got there and Tobe led me into the dining room. It was a fine, large room with one big table extending the entire length. It was neatly laid with china and pure white oilcloth. A smart looking young chinaman in a white coat and apron was bringing in the food. The lady of the house, a really beautiful young woman with luscious brown hair, neatly clad, was helping the chinaman set the table. I was given a seat near the head of the table, and my friend, Tobe, sat next to me. Pretty soon the cowboys came filing in from the barroom and gave me queer, fleeting glances. When we were nearly through with the meal, a poor wretch came stumbling in, pretty drunk from the barroom. The proprietor, a big, fine looking man, took the poor fellow out into the washroom; and after he was washed up, he brought him back and let him have something to eat. The proprietor and the lady of the house were man and wife and had only been in this. country a few years. They were from London. She used to be a barmaid. About once a week she used to get pretty tipsy, but her husband seemed to take her arm and put her to bed if she got too wobbly. I was given a nice little room opening into the parlor. She had a melodeon, if anyone remembers what sort of musical instrument that was, which she played until late and kept me awake most of the night.

The next morning, having had a conference with the trustees, I was ready for business and walked to the schoolhouse a few blocks from the hotel. There were about six little boys and girls gazing at me in awe and wonderment. I unlocked the schoolhouse, which felt like an oven. I rang a funny little bell, and the children came in and took their seats. There were many fine maps hanging on the wall. One boy wanted to go for a bucket of water, and we surely needed it. I sprinkled the floor and sent him for more. This cooled things off a bit. There was a good sized blackboard, a fine globe of the world, and a number of good books in the bookcase, which had never been read (too old for the children). There was a good stove for cold weather but it was full to the top with old papers, trash, and mice; and when I opened the door, they scampered in all directions.

Well, here I stayed and taught the youngsters one thing and another. But one Jewish family who had a little boy and girl in school used to tell me to come and take the children out driving after school. They had a fine span of jet black horses who were just raring to go. We used to get into the light spring wagon and drive for miles over fine roads. I never supposed I would have to cross the Salinas River again, but this time I was a mere . My friend, Tobe, was a telegraph operator and stage station agent in San Miguel. His wife was a beautiful and charming person. She had been a school teacher in San Jose. Long after I left there they separated. He went back to Yreka where his people had a fine home and were quite well off. I often went to church in the old Mission building to see the native Indians praying on the earth floor. There was a large window in the top of the building, and a few painted panels. An old Spanish priest used to say mass and pray for the natives.

After finishing my school at San Miguel, I took one near the coast and not so far from San Luis Obispo. It was much the same kind of school, only about ten pupils, but I had a miserable place to board in a private family. They did not know how to cook anything but beans, and the whole place was dirty and untidy. They ran a dairy, and occasionally I could get some milk to drink. The schoolboard paid a good salary, $60.00 I think, but I was glad the day I left there and went to San Luis Obispo.

In San Luis I got a job in an abstract office as I was familiar with this kind of work in Yreka after the big fire. It was the middle of summer, and no schools to teach. This abstract office was in the County Court House. It was mild and cool. I put what money I had saved from teaching into the San Luis Bank. I did not get such a good salary in this office, but it was better than being idle. I sent a few dollars home once in a while, as my parents were getting old. The mines had "retired" out, and my Father was not much of a farmer. I taught school for a short while in San Luis when they happened to need a teacher for a few weeks. I was always planning to go back to San Jose as I had only six months to complete my Senior year and then I would have been given a life Diploma. But something always prevented my going. The oil, or rather asphalt boom, as they had found an asphalt pit or mine near there, and a short real estate fellow endured me to take my money out of the bank and buy asphalt stock. That was the end of that money.

It was now fall and I took a school up the coast near San Simeon, on the Hearst Ranch. I did not live on the Ranch, though Willy Hearst used to come down often on one of the little that always called there. He would often give a dance in his big Ranch House and have all his cowboys and whatever girls there were, and some old country fiddlers come in. Then we would dance til broad daylight; and Willy, the best "stepper" of all would dance with me. I often wonder if he ever thinks of these old days when he entertains the elite of the land in his grand new mansion built on the Hearst Ranch. When I finished my school at San Simeon, I went back to San Luis Obispo. I did not have very much pleasure. What I remember most was the wonderful view from the little schoolhouse where you could see the great ships passing by, and hear the mighty roar of the ocean. When school was out, I used to walk down the high bank to the beach and watch the white breakers roll in. It was a fine, wide, sandy beach which extended for miles down the coast. I would feel lonely at times if it was not for a little bird that uttered a plaintive cry and used to keep close to me as I walked for a mile or more along the beach before I would return to my room, generally at dusk. Then I would recall that beautiful poem "One little sandpiper and I". Yes, it was a little sandpiper that had flit up and down the beach with me. I can not recall the poem now, or the author, but some day I will find it and copy it here.

When I left San Simeon and returned to San Luis Obispo, I got my old job back in the abstract office. The salary was small, but I was glad to get it as the only money I had was from my school at San Simeon. I did not have a bank account anymore. The Asphalt Mine got that.

A very charming girl, with whom I used to room, worked in the abstract office with me. One day she said she was awful tired of the abstract office and her low salary. Some friends had written her to come to San Diego. It was the beginning of the big Western Boom. They said she would not have any trouble getting a good job at good wages. She begged me to go with her. She was leaving the next day. The only thing that prevented my going was the lack of money. I was terribly sad when she left. She wrote me often. Got a good job, and after a year married a wealthy man from the East. So, in another year instead of going South I came North to far away Seattle.

My Mother, Bridget Quinlan, was born in the village of Ross Crea, not far from the City of Limeric, Ireland. She came to Montreal, Canada with an older sister and her husband, in the year 1847. On Christmas day 1849, she was married to my Father, a young man about twenty years of age. They made their home in Montreal where my Father was a tutor in wealthy families. About 1850 they moved with my Mother's relatives to Wisconsin, as the U.S. government was giving large farms to settlers. My Mother's first child - a boy - was born on a prairie in Wisconsin. The Indians used to come to the rude cabin to look at the little white child, much to my poor Mother's discomfort, for these Indians were dressed in robes of skins and wore moccasins on their feet. A second child, another boy named Thomas Weston Macaulay, was born there also. He lived to a good old age and died in San Francisco in 1929.

About 1851, the Gold excitement reached the people in the east. Upon hearing this my Father gave up farming, for which he was totally unfitted, and prepared to leave at once for the land of Gold (California). My poor Mother was broken hearted as she worshipped my Father and it might be for years, or maybe forever, before she would see him again. It was an easy matter to sell the farm on Dell Prairie, Wisconsin for a large sum: And, it was enough to take my Father on the long journey to California, and to provide for my Mother and her two children for a year or more. As soon as Father was gone, my Mother moved into her sister's family and continued to live there, in Portage City, for seven years. Her first son died when he was four years old.

My Mother received a letter and some money for her to go out to California. So, she began to get ready for the long trip. My brother, Thomas, was then eight years old. They left Portage City and went to New York, and then by water to the Isthmus of Panama. It was a tempestuous voyage, but nothing to what lay ahead of her. I do not remember her telling me about crossing the Isthmus, but she and my brother were put aboard a steamer which finally reached San Francisco. She received a letter there from my Father telling her to cross the San Francisco Bay and take a train to Sacramento. This was a terrible shock to my Mother as she expected, after her long sea voyage, to see my Father in San Francisco.

Once in Sacramento, the train terminus, she was introduced to a new kind of transportation. Early the next morning she was awakened by a gruff voice saying, "Hurry and dress as the mule train is all saddled and ready to start." She and brother ate a hurried breakfast and were ready. My poor Mother was shocked when a man approached her and said, "Now, lady, I'll help you up into the saddle. This mule is very gentle and used to carrying women, but you are the only lady passenger today. I have a nice little curly mule for the boy to ride." Of course, my brother was delighted. My Mother had never been on a horse and she had never heard of a mule. It was a long train, the passengers all men, going to the various 'gold diggins'. My Mother had to be lifted off of the mule whenever they reached the stopping place at the close of the day. Mother told me that if it had not been for my brother, she could have gone no further. But, finally, after traveling for over a week, over mountains, rough, trails and hazardous canyons, she reached her destination at a little place by the name of "Callahan's Ranch". There was a good hotel in this flourishing mining camp. Located in the heart of the Siskiyou Mountains about seventy miles west and south of Yreka. But my Father was not there to meet them. My Father's partner was there, and he took them over a rough trail about five miles to her final home---a rude log cabin in a great forest. Father came out to meet them. Mother hardly knew him; the past seven years had changed him greatly. The only thing that seemed to cheer my Mother was a huge fireplace, and on the hearth there was a big pot of pork and beans. She was so tired and so hungry that I guess she thought more about eating than anything else. My Mother did not tell me any of the details that took place upon her arrival at the cabin, or anything more until in the course of two years I was born, March 6th, 1861. My dear Mother was all alone, no doctor or nurse. She sent my brother to the village three miles away for help. A neighbor there came at once and did everything she could. I relate this to show what the pioneer women often had to endure.

One dark night when I was sleeping in my wooden cradle, Mother and my brother heard some crying and unearthly yells not far from our cabin. With the dim light of a lantern they went out to offer help. The noise ceased, but very close to them they saw two gleaming eyes, then a fierce growl. It was a cougar, often called a California Mountain Lion. My Mother often told me of another happening that gave her a great fright. A band of Indians had camped near by. There seemed to be two factions. They were fighting and 'pow-wowing'. There were several ponies tied to the trees. Presently, they dragged a young Indian girl over and threw her onto a pony. Several Indians mounted the ponies and rode away toward the high mountains. The Indians that were left in the camp started a war dance with dismal yells and pow-wows. By night they, like the Arabs, folded their tents and silently slipped away.

My brother, Thomas, never did go to school as there were no schools within walking distance. Mother and Father taught him to read and write. In the winter, when there was enough water for mining, he worked with my Father; and in the summer he cut cordwood to be sold. My Father was a hard master and expected by brother to work like a man. When he was fifteen he ran away and worked in a mine about forty miles from our place. Once a year he came back to see Mother and me.

MARCH 31, 1938

Tom always had his gun with him and would bring a fine grouse for Mother to cook. Mother worried and grieved all those years about Thomas.

On one occasion when he came home, it was after dark and I ran to meet him. He stooped down to kiss me. My little dress caught in the trigger of his gun; and, fortunately, as it was resting on the ground upright, the shot went up, just mis¬sing my head. From that day, I have been afraid of firearms of every kind.

Two years after I was born, we moved farther down the creek, rightly named "Wild Cat". This was a large well-built cabin. Here my only sister, Margret Ann, was born, September 6, 1863. She had a hard life before her, full of sorrow and disappointment. Her husband, T. J. Ankeny, died several years before her; and her only child, Miss Pauline Ankeny, is now a teacher in the public schools of Los Angeles. My sister died in March 1937.

When Maggie and I were little children, we moved again, about two miles farther down the creek. My Father settled upon a nice piece of land among the hills and built a small house of lumber--no more log cabins. Mother was well pleased, and Father located a good paying gold mine within walking distance of the house, where sister and I grew up. We attended the public school at 'South Fork', nearly three miles away, walking over a mountain trail. I forgot to mention that my Mother took the County School Exam for school teachers and passed creditably. She was educated in a convent in Ireland. My Mother was engaged to teach the first public school in that part of the county which was in the mining camp on East Fork. She had to move into another log cabin, as it was impossible to walk back and forth night and morning. I remember well sitting in the foot of the cradle with sister Mag, a little babe asleep in the other end, while Mother was teaching. When this school was finished, she continued to live on "Macauley Ranch" the rest of her life. My sister and her husband came to live with Mother and Father in 1894. Mother and Father were growing old, and Mag and Frank took care of them until both of them had passed away. My Father died in 1892; my Mother in 1909.

I was about 14 years old when I went to live with a friend of Mother's who lived at Callahan. There were three children in the family. The head of the family was away most of the time. He drove a six-mule team to Redding, the terminus of the R.R., and returned with a huge wagonload of freight for Callahan and Etna. The trip took about a month, Mrs. Blevins, Mother's friend, was a kind woman and took good care of her children and home. She taught me many useful things - to sew on a machine, to cook and help with the family washing and ironing (no small item). There were no such things as washing machines in those days. I worked hard but went home every Sunday to see Mother and sister. I stayed with Mrs. Blevins seven months. Then I went home to live and go to school in Callahan.

I had nearly three miles to walk back and forth to school. The next year when school closed, I heard of another position, much farther away. But I was to teach the children and reserve $20.00 per month. This place was a large hotel or summer resort, near the town of Trinity Center in Trinity County. I had to travel in a big overland, four-horse stagecoach which, of course, was all new to me. Leaving Callahan in the evening, we rode all night over a rough mountain road, the horses going at a quick trot. I was thrown from side to side in the stage until I was so bruised and sick I could hardly get out when I reached the hotel.

The next day my duty as teacher for the children began. There were four boys and a little girl. The boys were unruly; and when they saw a girl of 15, not much older than themselves, they did about as they pleased. I soon was told there were many things I could do besides teach. Anyway, I learned to be a waitress, a chambermaid, a laundress; and when there was nothing else to do, I could close the toll gate in front of the hotel and let no team pass until I collected the money. I stayed in this place a year. After being there two or three months, another girl was brought to teach the little girl music. A fine new square piano was placed in the parlor, the first piano I had ever seen. The music teacher came from San Francisco and was a fine musician, and also my own age - 15. We soon became chums. I took an occasional music lesson from her, and she said I learned rapidly.

APRIL 4, 1938

After the little music teacher left for San Francisco, I continued to live at the Summer Resort until I had been there a year. Then it dawned upon me that I was growing up without an education - the thing I had always desired. So, I boarded the old stagecoach and finally arrived at Callahan. I went into the hotel to rest, and the proprietor and his wife, who had known me all my life, said they needed help badly and would pay me $15.00 a month. I agreed, but first went home - three miles - to visit my Mother and sister before I began to work at the Callahan Hotel. They were very kind to me and let me practice on their new piano whenever I had time. I went there in the fall, and after being there several months, Mrs. Hayden said she wanted to take a trip to Yreka, the County seat, and 40 miles north of Callahan. I was delighted when she planned to take me along. She knew I wanted to attend school, and as she knew several good families there, said she would find me a place where I could work for my room and board and go to school. I entered the High School, as I had finished grammar school two years previous in South Fork and Callahan. I was now 17 years old. When I was 19 I graduated from High School soon after I took the Teacher's Exam and passed receiving a primary County Certificate. Then a school was offered to me 40 miles away, north of Yreka near the Klamath River. The people I boarded with were rather old people and had a good ranch with oceans of cream, milk and butter. Also, a fine orchard with an abundance of fruit. The schoolhouse was four miles from my boarding place. So, I bought a horse, a dear little gentle animal, and named her Lady Jane. My pupils were mostly Indian children and several halfbreeds. They were good children, easy to manage.

About this time I met a dear girl, Ella Sheppard, another schoolmarm who taught not many miles away, over in the State of Oregon. She too had a pony and used to ride down to my school quite often. She wanted to organize a Sunday School for the children. She used to illustrate the lessons on the blackboard with colored crayon, and the children seemed to understand as more of them attended. Her pupils were mostly Indians, as she could speak the Chinook language. She and I used to have such good times in the glorious, picturesque country. The mighty Klamath River, deep and swift, was only a few feet from my schoolhouse. Near the river bank were high cliffs of rock that no one tried to climb. Ella and I would ride for miles up the river until it was time for her to come back and catch the ferry that would take her back to the Oregon side. In the autumn, our schools closed, and I said farewell to Ella. What a dear, vivacious girl she was. I wonder where she is now!

Soon after school closed, until the next spring, I returned to Yreka. There I secured a nice room and stayed for a time. I visited my brother and his family who lived over the mountains a few miles away. I returned to Yreka in the spring. I heard they wanted a teacher in the place where I first went to school, South Fork. They gave it to me, and I lived at home with Father and Mother. Maggie had gone out to work in families in the neighborhood. I had only a few pupils here, some of them almost my own age. My parents were so happy to have me home with them, and the money I usually paid for board was a help also. When this school closed in the fall, I heard of a winter school over at Mt. Shasta, about 60 miles away. This was a community of well-to-do ranchers. They had fine horses and carriages and large herds of cattle. I boarded with a nice family where there were young people, and I had only a short distance to walk to school. This was fortunate as it was a winter school and very deep snows fell there being so close to Mt. Shasta. I did not have many pupils, and they were very nice young people. I used to go horseback riding with three or four others right up to the side of the great mountain. There were dances in the town of Sisson, not far away, and I often think of the gay life I had when I lived there. My school closed in the spring and so I planned to go "down below", as everyone said, and attend the State Normal School in San Jose. I received $75.00 per month for nine months of school. California always paid its teachers well. I went back to Callahan to see my parents, then to Yreka, where I was met by a girl I knew who was going to go to the Normal School also. We boarded the big four-horse overland stage at Yreka and were off. It was a hard journey, two days and a night before we reached the terminus of the R.R. at Redding, California. This was my first sight of a train and locomotive. I was just 21 then. I'll admit it frightened me and filled me with wonder. I could not imagine why a locomotive should make such an awful noise. When we entered the passenger coach, I was bewildered. The conductor in uniform punching tickets and putting little slips of paper in men's hats. We left early in the morning and reached the great city of San Francisco at night. How amazed we were at the bright lights, though that was a long time before the invention of electric lights. We went to a hotel. The next day a friend to whom we had written took us on the street cars for a tour of the beautiful city.

The next day our friend took us across in the ferry to Oakland where we took the train to San Jose. This was through the most beautiful gardens and parks I had ever seen. In a few hours we reached San Jose - a very pretty city. We could see the Normal School and were amazed at its size. That afternoon we secured a room with other students near the school.

The next morning, we went to enroll. We waited a long time in a big office. Finally, a gentleman entered and questioned us very thoroughly. At last he said I could enter as a high Junior, as I had taught two years: I finished my junior year, but as my funds were getting low, I had to go back to Siskiyou and get a school again. I cannot remember now where I taught, but the trustees wanted me to return for the next term. Another teacher and I went back to Yreka for the winter. We planned to study for 1st grade certificates, but something prevented us from doing so. We secured a very nice room in an ex-Judge's family. He'd passed away but a short time before! His widow was a dear, kind person, not much older than we were, though she had three or four young children. I do not know how the poor woman existed as the neighbors told us the Judge had left very little besides the home. But she did not charge us very much for the nice room. However, one day I read a letter from an old

friend of mine that I used to know when I worked at Callahan. He was a telegraph operator then as well as a lineman. The two jobs went together in those days. He was an exceedingly witty fellow and very well educated, also very good look¬ing except that he had but one eye. That didn't seem to bother him, though. He had many friends. Everyone liked him. But I must get back to the letter he wrote me from away down in San Luis Obispo County. He was married now and had a very beautiful wife, though she was a cripple who used to walk with a cane. Anyway, Tobe wanted me to come down at once and take a very good school with only a few pupils. They were looking for a teacher everywhere and could not find one. The salary was $65.00 per month. It did not take me long to decide, as I was getting awful tired of Yreka and Siskiyou. However, I went back to Callahan to tell my Mother and Father goodbye. I took the overland stage from there to Redding, California. There I took the train to Salinas in Southern California. That was the most terrible trip I ever had in my life!! But I finally arrived in Salinas after a terrible, bumpy ride in that R.R. coach. All day it was rain¬ing very hard, and I was hurried into a stagecoach, and we were off again. Another day and night of being bumped off one seat and onto another, occasionally hitting my head against the cover of the coach. Another lady passenger was with me. It was her first experience with anything of this kind and she moaned and wept and cursed the day she ever heard of San Luis Obispo. When morning broke and the green hills were on all sides with the warm sunshine, one almost forgot the miseries of the night. But it wasn't so beautiful after all. We were at the brink of a great rolling, muddy river with no bridge in sight. The stage driver began unhitching the horses and preparing for the trip back. Away on the far bank of the river we saw a man in a rowboat trying to come for us. He finally got to our side and the boat struck bottom. He told me to come as close to him as possible and jump on his back and he would put me in the boat. He did likewise with the other poor woman, though she was sobbing all the time. She put her arms around his neck and he took hold of her legs and finally dumped her in the boat. He had a hard time rowing us across as the great waves of sand were hard to pull against. There was a stage waiting for us on the other side and the driver helped to get us out of the boat onto dry land. We rode along the banks of the mighty Salinas River for a few miles. It was a beautiful sunny morning, the bright green hills and valleys made me glad I had come to Southern California after all the hardships. By noon we had reached my destination - Mission San Miguel. All that was to be seen at first was the old mission. It was in a pretty good state of preservation then -nearly 50 years ago. A little farther on we came to what was to be my home for nine months. My fellow passenger stayed in the stage another days' journey onto the city of San Luis Obispo. I never saw her again. The stage drove up to the hotel porch and there stood my friend, Tobe, all smiles to welcome me. This hotel was a one-story frame building with a big front erected from the top of the porch, and the whole building was whitewashed. There were three or four windows and two doors. One of these doors was the barroom for men only. A lot of saddle horses were hitched out front with Mexican saddles, lariats, and jingling spurs hung on the sides of the saddles. It was just dinner time when I got there and Tobe led me into the dining room. It was a fine, large room with one big table extending the entire length. It was neatly laid with china and pure white oilcloth. A smart looking young chinaman in a white coat and apron was bringing in the food. The lady of the house, a really beautiful young woman with luscious brown hair, neatly clad, was helping the chinaman set the table. I was given a seat near the head of the table, and my friend, Tobe, sat next to me. Pretty soon the cowboys came filing in from the barroom and gave me queer, fleeting glances. When we were nearly through with the meal, a poor wretch came stumbling in, pretty drunk from the barroom. The proprietor, a big, fine looking man, took the poor fellow out into the washroom; and after he was washed up, he brought him back and let him have something to eat. The proprietor and the lady of the house were man and wife and had only been in this. country a few years. They were from London. She used to be a barmaid. About once a week she used to get pretty tipsy, but her husband seemed to take her arm and put her to bed if she got too wobbly. I was given a nice little room opening into the parlor. She had a melodeon, if anyone remembers what sort of musical instrument that was, which she played until late and kept me awake most of the night.

The next morning, having had a conference with the trustees, I was ready for business and walked to the schoolhouse a few blocks from the hotel. There were about six little boys and girls gazing at me in awe and wonderment. I unlocked the schoolhouse, which felt like an oven. I rang a funny little bell, and the children came in and took their seats. There were many fine maps hanging on the wall. One boy wanted to go for a bucket of water, and we surely needed it. I sprinkled the floor and sent him for more. This cooled things off a bit. There was a good sized blackboard, a fine globe of the world, and a number of good books in the bookcase, which had never been read (too old for the children). There was a good stove for cold weather but it was full to the top with old papers, trash, and mice; and when I opened the door, they scampered in all directions.

Well, here I stayed and taught the youngsters one thing and another. But one Jewish family who had a little boy and girl in school used to tell me to come and take the children out driving after school. They had a fine span of jet black horses who were just raring to go. We used to get into the light spring wagon and drive for miles over fine roads. I never supposed I would have to cross the Salinas River again, but this time I was a mere . My friend, Tobe, was a telegraph operator and stage station agent in San Miguel. His wife was a beautiful and charming person. She had been a school teacher in San Jose. Long after I left there they separated. He went back to Yreka where his people had a fine home and were quite well off. I often went to church in the old Mission building to see the native Indians praying on the earth floor. There was a large window in the top of the building, and a few painted panels. An old Spanish priest used to say mass and pray for the natives.

After finishing my school at San Miguel, I took one near the coast and not so far from San Luis Obispo. It was much the same kind of school, only about ten pupils, but I had a miserable place to board in a private family. They did not know how to cook anything but beans, and the whole place was dirty and untidy. They ran a dairy, and occasionally I could get some milk to drink. The schoolboard paid a good salary, $60.00 I think, but I was glad the day I left there and went to San Luis Obispo.

In San Luis I got a job in an abstract office as I was familiar with this kind of work in Yreka after the big fire. It was the middle of summer, and no schools to teach. This abstract office was in the County Court House. It was mild and cool. I put what money I had saved from teaching into the San Luis Bank. I did not get such a good salary in this office, but it was better than being idle. I sent a few dollars home once in a while, as my parents were getting old. The mines had "retired" out, and my Father was not much of a farmer. I taught school for a short while in San Luis when they happened to need a teacher for a few weeks. I was always planning to go back to San Jose as I had only six months to complete my Senior year and then I would have been given a life Diploma. But something always prevented my going. The oil, or rather asphalt boom, as they had found an asphalt pit or mine near there, and a short real estate fellow endured me to take my money out of the bank and buy asphalt stock. That was the end of that money.

It was now fall and I took a school up the coast near San Simeon, on the Hearst Ranch. I did not live on the Ranch, though Willy Hearst used to come down often on one of the little that always called there. He would often give a dance in his big Ranch House and have all his cowboys and whatever girls there were, and some old country fiddlers come in. Then we would dance til broad daylight; and Willy, the best "stepper" of all would dance with me. I often wonder if he ever thinks of these old days when he entertains the elite of the land in his grand new mansion built on the Hearst Ranch. When I finished my school at San Simeon, I went back to San Luis Obispo. I did not have very much pleasure. What I remember most was the wonderful view from the little schoolhouse where you could see the great ships passing by, and hear the mighty roar of the ocean. When school was out, I used to walk down the high bank to the beach and watch the white breakers roll in. It was a fine, wide, sandy beach which extended for miles down the coast. I would feel lonely at times if it was not for a little bird that uttered a plaintive cry and used to keep close to me as I walked for a mile or more along the beach before I would return to my room, generally at dusk. Then I would recall that beautiful poem "One little sandpiper and I". Yes, it was a little sandpiper that had flit up and down the beach with me. I can not recall the poem now, or the author, but some day I will find it and copy it here.

When I left San Simeon and returned to San Luis Obispo, I got my old job back in the abstract office. The salary was small, but I was glad to get it as the only money I had was from my school at San Simeon. I did not have a bank account anymore. The Asphalt Mine got that.

A very charming girl, with whom I used to room, worked in the abstract office with me. One day she said she was awful tired of the abstract office and her low salary. Some friends had written her to come to San Diego. It was the beginning of the big Western Boom. They said she would not have any trouble getting a good job at good wages. She begged me to go with her. She was leaving the next day. The only thing that prevented my going was the lack of money. I was terribly sad when she left. She wrote me often. Got a good job, and after a year married a wealthy man from the East. So, in another year instead of going South I came North to far away Seattle.

Gravesite Details

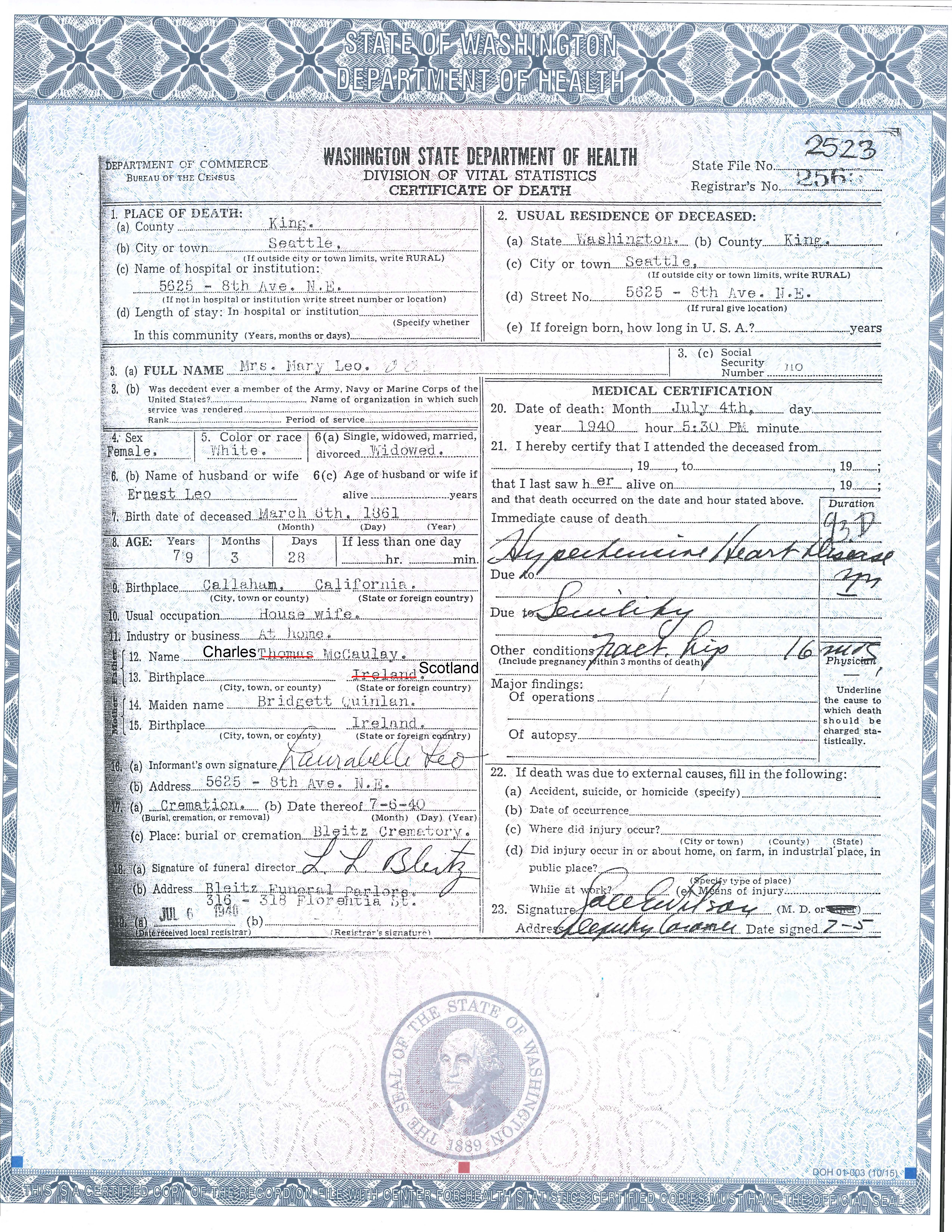

Contacted Bleitz and they had no record of inurnment.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement