Published: LDS Church News, Saturday, July 13, 1996

More than 150 years ago, a group of Latter-day Saints began a trek to the Rocky Mountains that was both farther and earlier than the famous Mormon pioneer wagon train of 1847.

This group, known as the Mississippi Saints and often forgotten by history, formed a community within the Church that made many contributions to the settlement of the West.On May 25 this year, members in Monroe County honored these early pioneers by dedicating a monument at Mormon Springs where many of the early Mississippi converts were baptized.

The granite monument is 4 feet high by 8 feet long. The legend on the monument recounts the story of the Mississippi Saints and states:

"Many of these early converts were marvelous frontiersmen, resourceful colonizers and shrewd traders. Because of their abilities, nearly all were eventually called to lead Mormon colonies to Colorado, Utah, California, Oregon and other areas of the West. They were valiant in their love of God, their prophet and their religion."

Pres. T. Evan Nebeker of the Tupelo Mississippi Stake presided as descendants of these faithful Saints met to venerate their ancestors. About 250 people attended, from such far-away places as Idaho, Utah, California, Florida and Virginia. Among them was a great-grandson of John Brown, the missionary who helped organize the wagon train.

Pres. Nebeker, a descendant of William Harvey Lay, one of the pioneers from Monroe County, said, "We gather here today to remember and honor those who once walked these hills and valleys, who built and cultivated, who married, raised families and worshiped the living God.

"When the angels see our labors, may they witness the depth of our gratitude for those who sacrificed so much. We remember them, black and white, young and old.

"May this site be a place of peace to all who stop here to rest, or reflect or remember. May we never forget."

According to Southern Grace, a history of the Mississippi Saints by Charmaine Lay Kohler, and other historical sources, these Southerners thrived on the frontier. Many were the children of plantation owners to the southeast who had pushed into Mississippi looking for new, fertile land. The missionary who introduced many of them to the restored gospel was a fellow Southerner, Elder John Brown of Kentucky. In 1843, Elder Brown was called to preach in Kentucky, Alabama and Mississippi. When he arrived in Monroe County that year with his companion, Elder Haden W. Church, they found a branch earlier created by Elder Benjamin Clapp. They strengthened the branch and Elder Brown baptized a wealthy widow, Elizabeth Crosby, and her daughter Betsy, whom he later married. William Crosby, a son, had been baptized earlier.

"We preached in almost every neighborhood for several miles around, also in some of the towns and villages in the adjoining counties," wrote Elder Brown in his journal. "We often had to wade in water up to the waist and cross the main streams and deep water in canoes to get to our appointment. But . . . the Lord was with us and blessed our labors."

The labors of Elder Brown and other missionaries yielded a rich harvest, many of whom remained faithful all their lives.

Three years later as the main body of the Church was in the midst of the Nauvoo exodus, Elder Brown was called to help organize a group of about 60 people from northeast Mississippi into a pioneer company.

At this time the main body of Saints was struggling across Iowa, fully intending to travel to the Rocky Mountains that summer. The Mississippi Saints were to come north and join the trek. That rendezvous with the Mississippi and main body of Saints would wait a year, however. Unknown to the Southern members, the U.S. government mustered 500 Latter-day Saint exiles into the military to form the Mormon Battalion. This was a primary factor in Brigham Young's wise decision to wait a year before crossing the plains.

In Mississippi, the group elected Elder Brown's brother-in-law, William Crosby, as leader. The wagons embarked for the West April 8, 1846. At first the wagon train traveled north, angling west near St. Louis, Mo. It reached Independence, Mo., on May 26, in time to hear wild rumors of Mormons robbing wagon trains. In this tension-filled atmosphere, the group elected to keep its identity to itself. The wagon train quietly joined an Oregon-bound company, and veered toward the Oregon Trail.

On the way to the Platte River, they stopped to assist a trader named "Jose," whose boat had lodged on a sandbar. He joined their party and provided plains expertise for the hardy Southerners. The caravan arrived at the Platte River probably in mid-June and found no Mormon wagon trains. This sobering discovery brought the caravan to a halt while the people counseled with each other. They decided that the wagon train surely must have gone ahead on the north side of the river. So they followed.

After they had been on the trail three months they met a returning group of trappers whogave them disheartening news: there were no Mormons ahead of them on the trail.

Farther west, the Mississippians met another trader, John Richards, who was schooled in the ways of Indians. He traveled with them and helped them avert difficulties with the occasional hunting parties of the plains. Richards invited the pioneers to winter with him at Fort Pueblo, 300 miles south of the main trail along the Arkansas River. The Mississippians accepted the offer and traveled to the small facility. They built cabins, planted crops and erected a meetinghouse.

Although the Mississipians were disappointed to have anticipated the Mormon migration by a full year, history's accident proved providential for those in the Mormon Battalion who had become sick. The Mormon settlement in Pueblo saved many of their lives.

The Pueblo Colony was being established as the Mormon Battalion traveled toward the disputed southwest. In the meantime, John Brown, William Crosby and D.M. Thomas left Pueblo and returned east to get their families. On Sept. 12, these men came across the Mormon Battalion in its southwestward march. Learning of the Pueblo settlement, Lt. Andrew Jackson Smith, temporary commander of the Battalion, dispatched the first of three groups from the Battalion to winter at Pueblo. These three groups included wives and children of Battalion members, soldiers who were sick or old, and escorts. The travail of the third group's journey to Pueblo in the winter with few provisions constitutes a largely omitted chapter of suffering and privation in Church history. These sick soldiers arrived in a destitute condition. Their arrival in Pueblo brought the population of the community to a total of 275. During the mild 1846-47 winter, the settlement had adequate provisions and the sick men recovered their health.

In the meantime, John Brown and his companions returned to Mississippi and then, with a few hand-picked men, including African-American slaves of Mississippi members, traveled to Winter Quarters. There, Brown joined the 1847 original pioneer company as one of the captains. The others also joined the company. This company crossed the prairie and arrived at Fort Laramie, Wyo., June 3, 1847.

Waiting at the fort for the first company were 17 Mississippi Saints and Battalion members who had come from Pueblo hoping to join the vanguard company. Amasa Lyman of the Quorum of the Twelve was sent to Pueblo to bring the rest of the colony along.

After arriving in the Salt Lake Valley on Oct. 16, 1847, the Mississippi Saints established a settlement called Cottonwood, or Mississippi Ward, that was later called Holladay after an early ward bishop.

In 1851, many of these Mississippi members followed Apostle Charles C. Rich to settle San Bernardino, Calif. They followed a difficult route across the Mojave Desert and faced the privations of settling again. But this time they established profitable farms in the fertile California soil. The advance of Johnston's Army in 1857 and the so-called Utah War prompted a call for the settlers to return to Utah. Most again gave up their homes in obedience to the prophet's call.

Representative of the fidelity of the Mississipians was William Harvey Lay, and his wife, Sytha Crosby Lay. "Billy," as he was called, was never baptized, but was loyal to the Church to the end. He left his home for a time in 1845 with John Brown and helped defend a besieged Nauvoo. The following year he crossed the plains with the Mississippi Saints to Pueblo. Then he returned to Mississippi for his family and brought them to the Salt Lake Valley. He was among those who traveled the dust-choked trail to San Bernardino where he established a prosperous farm. At the prophet's call, he sold his farm and crossed the desert again. The Lays spent the rest of their lives farming in arid southern Utah. He donated a team to help build the St. George Temple, and Sytha was the fourth woman to go through the dedicated temple.

Billy and Sytha are buried in the Santa Clara Cemetery beneath a tall red tombstone. Sytha died first, in 1881. Billy died in 1886. On his deathbed, he asked his youngest son, William, if Sytha had ever been sealed to anyone else.

"She only wanted you," William told his dying father. A smile of relief touched the weathered face as the old pioneer died.

The Lays and other Mississippi Saints left behind a legacy of obedience, strength and testimony that has been carried throughout the world by their descendants.

Thank you SMSmith for the above info

Published: LDS Church News, Saturday, July 13, 1996

More than 150 years ago, a group of Latter-day Saints began a trek to the Rocky Mountains that was both farther and earlier than the famous Mormon pioneer wagon train of 1847.

This group, known as the Mississippi Saints and often forgotten by history, formed a community within the Church that made many contributions to the settlement of the West.On May 25 this year, members in Monroe County honored these early pioneers by dedicating a monument at Mormon Springs where many of the early Mississippi converts were baptized.

The granite monument is 4 feet high by 8 feet long. The legend on the monument recounts the story of the Mississippi Saints and states:

"Many of these early converts were marvelous frontiersmen, resourceful colonizers and shrewd traders. Because of their abilities, nearly all were eventually called to lead Mormon colonies to Colorado, Utah, California, Oregon and other areas of the West. They were valiant in their love of God, their prophet and their religion."

Pres. T. Evan Nebeker of the Tupelo Mississippi Stake presided as descendants of these faithful Saints met to venerate their ancestors. About 250 people attended, from such far-away places as Idaho, Utah, California, Florida and Virginia. Among them was a great-grandson of John Brown, the missionary who helped organize the wagon train.

Pres. Nebeker, a descendant of William Harvey Lay, one of the pioneers from Monroe County, said, "We gather here today to remember and honor those who once walked these hills and valleys, who built and cultivated, who married, raised families and worshiped the living God.

"When the angels see our labors, may they witness the depth of our gratitude for those who sacrificed so much. We remember them, black and white, young and old.

"May this site be a place of peace to all who stop here to rest, or reflect or remember. May we never forget."

According to Southern Grace, a history of the Mississippi Saints by Charmaine Lay Kohler, and other historical sources, these Southerners thrived on the frontier. Many were the children of plantation owners to the southeast who had pushed into Mississippi looking for new, fertile land. The missionary who introduced many of them to the restored gospel was a fellow Southerner, Elder John Brown of Kentucky. In 1843, Elder Brown was called to preach in Kentucky, Alabama and Mississippi. When he arrived in Monroe County that year with his companion, Elder Haden W. Church, they found a branch earlier created by Elder Benjamin Clapp. They strengthened the branch and Elder Brown baptized a wealthy widow, Elizabeth Crosby, and her daughter Betsy, whom he later married. William Crosby, a son, had been baptized earlier.

"We preached in almost every neighborhood for several miles around, also in some of the towns and villages in the adjoining counties," wrote Elder Brown in his journal. "We often had to wade in water up to the waist and cross the main streams and deep water in canoes to get to our appointment. But . . . the Lord was with us and blessed our labors."

The labors of Elder Brown and other missionaries yielded a rich harvest, many of whom remained faithful all their lives.

Three years later as the main body of the Church was in the midst of the Nauvoo exodus, Elder Brown was called to help organize a group of about 60 people from northeast Mississippi into a pioneer company.

At this time the main body of Saints was struggling across Iowa, fully intending to travel to the Rocky Mountains that summer. The Mississippi Saints were to come north and join the trek. That rendezvous with the Mississippi and main body of Saints would wait a year, however. Unknown to the Southern members, the U.S. government mustered 500 Latter-day Saint exiles into the military to form the Mormon Battalion. This was a primary factor in Brigham Young's wise decision to wait a year before crossing the plains.

In Mississippi, the group elected Elder Brown's brother-in-law, William Crosby, as leader. The wagons embarked for the West April 8, 1846. At first the wagon train traveled north, angling west near St. Louis, Mo. It reached Independence, Mo., on May 26, in time to hear wild rumors of Mormons robbing wagon trains. In this tension-filled atmosphere, the group elected to keep its identity to itself. The wagon train quietly joined an Oregon-bound company, and veered toward the Oregon Trail.

On the way to the Platte River, they stopped to assist a trader named "Jose," whose boat had lodged on a sandbar. He joined their party and provided plains expertise for the hardy Southerners. The caravan arrived at the Platte River probably in mid-June and found no Mormon wagon trains. This sobering discovery brought the caravan to a halt while the people counseled with each other. They decided that the wagon train surely must have gone ahead on the north side of the river. So they followed.

After they had been on the trail three months they met a returning group of trappers whogave them disheartening news: there were no Mormons ahead of them on the trail.

Farther west, the Mississippians met another trader, John Richards, who was schooled in the ways of Indians. He traveled with them and helped them avert difficulties with the occasional hunting parties of the plains. Richards invited the pioneers to winter with him at Fort Pueblo, 300 miles south of the main trail along the Arkansas River. The Mississippians accepted the offer and traveled to the small facility. They built cabins, planted crops and erected a meetinghouse.

Although the Mississipians were disappointed to have anticipated the Mormon migration by a full year, history's accident proved providential for those in the Mormon Battalion who had become sick. The Mormon settlement in Pueblo saved many of their lives.

The Pueblo Colony was being established as the Mormon Battalion traveled toward the disputed southwest. In the meantime, John Brown, William Crosby and D.M. Thomas left Pueblo and returned east to get their families. On Sept. 12, these men came across the Mormon Battalion in its southwestward march. Learning of the Pueblo settlement, Lt. Andrew Jackson Smith, temporary commander of the Battalion, dispatched the first of three groups from the Battalion to winter at Pueblo. These three groups included wives and children of Battalion members, soldiers who were sick or old, and escorts. The travail of the third group's journey to Pueblo in the winter with few provisions constitutes a largely omitted chapter of suffering and privation in Church history. These sick soldiers arrived in a destitute condition. Their arrival in Pueblo brought the population of the community to a total of 275. During the mild 1846-47 winter, the settlement had adequate provisions and the sick men recovered their health.

In the meantime, John Brown and his companions returned to Mississippi and then, with a few hand-picked men, including African-American slaves of Mississippi members, traveled to Winter Quarters. There, Brown joined the 1847 original pioneer company as one of the captains. The others also joined the company. This company crossed the prairie and arrived at Fort Laramie, Wyo., June 3, 1847.

Waiting at the fort for the first company were 17 Mississippi Saints and Battalion members who had come from Pueblo hoping to join the vanguard company. Amasa Lyman of the Quorum of the Twelve was sent to Pueblo to bring the rest of the colony along.

After arriving in the Salt Lake Valley on Oct. 16, 1847, the Mississippi Saints established a settlement called Cottonwood, or Mississippi Ward, that was later called Holladay after an early ward bishop.

In 1851, many of these Mississippi members followed Apostle Charles C. Rich to settle San Bernardino, Calif. They followed a difficult route across the Mojave Desert and faced the privations of settling again. But this time they established profitable farms in the fertile California soil. The advance of Johnston's Army in 1857 and the so-called Utah War prompted a call for the settlers to return to Utah. Most again gave up their homes in obedience to the prophet's call.

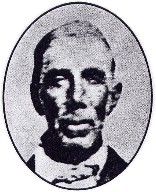

Representative of the fidelity of the Mississipians was William Harvey Lay, and his wife, Sytha Crosby Lay. "Billy," as he was called, was never baptized, but was loyal to the Church to the end. He left his home for a time in 1845 with John Brown and helped defend a besieged Nauvoo. The following year he crossed the plains with the Mississippi Saints to Pueblo. Then he returned to Mississippi for his family and brought them to the Salt Lake Valley. He was among those who traveled the dust-choked trail to San Bernardino where he established a prosperous farm. At the prophet's call, he sold his farm and crossed the desert again. The Lays spent the rest of their lives farming in arid southern Utah. He donated a team to help build the St. George Temple, and Sytha was the fourth woman to go through the dedicated temple.

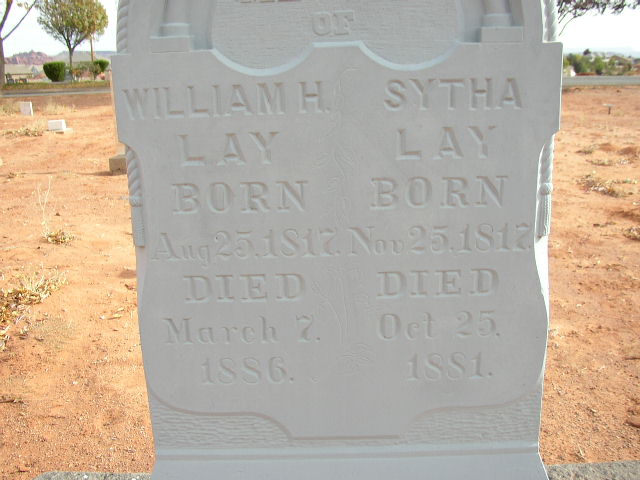

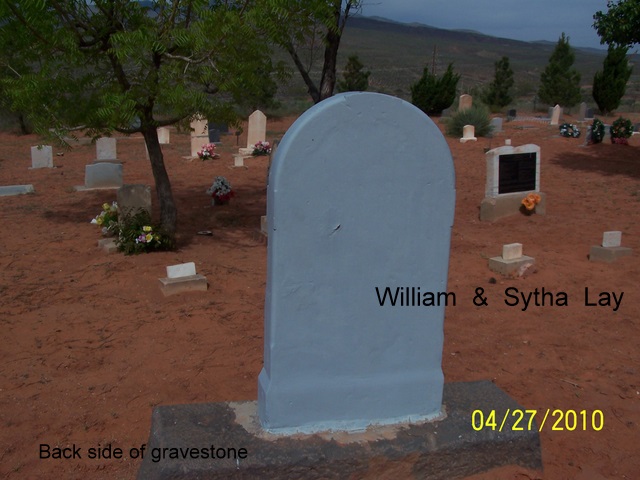

Billy and Sytha are buried in the Santa Clara Cemetery beneath a tall red tombstone. Sytha died first, in 1881. Billy died in 1886. On his deathbed, he asked his youngest son, William, if Sytha had ever been sealed to anyone else.

"She only wanted you," William told his dying father. A smile of relief touched the weathered face as the old pioneer died.

The Lays and other Mississippi Saints left behind a legacy of obedience, strength and testimony that has been carried throughout the world by their descendants.

Thank you SMSmith for the above info

Inscription

In Memory Of, Spouse: Sytha Lay

Family Members

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement