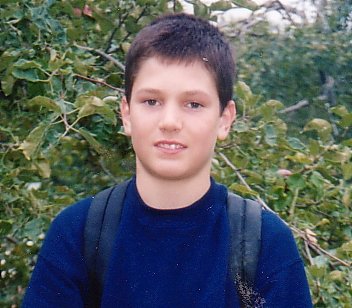

"A gentle giant," says his uncle Paul Chojnowski. Quinn has hands like a grown man's and an athlete's body that's been -- says his mother, Ann -- "sculpted and defined since age five." And so she develops the reverse concern of most hockey moms: Ann worries that her son will hurt someone else's child on the ice.

Quinn is smart -- in the 93rd percentile for IQ -- and maintains a B average at St. Stanislaus Kostka school in Adams, Mass. Anything lower and Steve won't let him play hockey. Never mind that Quinn was diagnosed with dyslexia in second grade and often asks, angrily and with deep frustration, "Why can't I read?"

His friends all devour the same books, and one evening Quinn announces that he intends to tackle an inch-thick Harry Potter. "So we laid belly-down, shoulder-to-shoulder, on his bed," says Ann. "And he started to read this long passage." It was like watching a high-wire act, and when Quinn, with scarcely a stumble, made it safely to the other side, he exhaled mightily and looked up from the page. For a long moment, says his mother, "We just looked at each other with these big smiles. Then Quinn said, 'O.K., Mom, I'm tired now.'" And he retired for the night.

Quinn is disconsolate if his father forgets to wake him for the 5 a.m. SportsCenter. The Connallys' front yard in Cheshire, Mass., is a lawn mower's minefield of Day-Glo pucks, golf balls, tennis balls and badminton birdies. After fracturing his right hand playing hockey, Quinn uses the cast as a paddle when playing Ping Pong in the backyard.

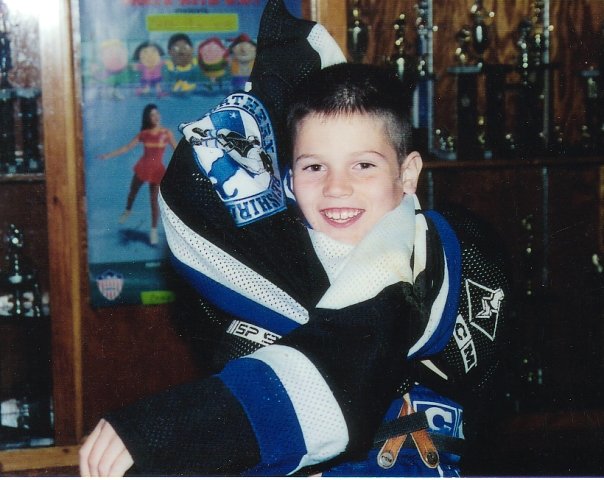

Quinn plays hockey like he reads Harry Potter. Slowly, yes, and without natural aptitude, but with such a doggedly competitive streak that after two seasons of tryouts he makes the MassConn Braves traveling team. Seldom has the phrase "traveling team" been so apt. The home rink is 70 minutes away, and it's not unusual for the family to travel six hours round-trip for a one-hour hockey game.

Thus a 75-minute drive to practice in Springfield is nothing. Or rather, it's something. Quinn does homework by domelight while Dad drives. "Real bonding time," Steve says of those rides.

At practice in the Springfield Civic Center, Quinn, a defenseman, slides to block a shot in a three-on-two drill. It is 6:15 p.m. when the puck strikes him in the back of the neck, just below the helmet. Steve hears another father say, "That didn't look good," and indeed, Quinn is taken to Bay State Medical Center, where his parents, and his teammates -- and their parents -- stay all night. "Hockey parents have a special connection," says Uncle Paul. "Maybe it's all those 5 a.m. ice times."

At 11:59 the next morning, the Connallys are told, unfathomably, that their son has died of a severed blood vessel. When they're asked, in the same breath, if they would be willing to donate Quinn's organs, the Connallys say, "Of course."

Quinn's death -- on Dec. 4, 2000 -- is reported as the first of its kind in youth hockey history. The Connallys receive cards from strangers in every one of the 50 states.

For two years Ann cannot enter an ice arena, and to this day she cannot bear to look at a Pee Wee-aged player. "With the big bag and stick?" she says. "Can't do it."

So it is astonishing that Ann should quit her job in retail management, and that Steve should leave his job as a "computer geek," to devote their working lives to one purpose: building a two-rink arena (and community/tutoring center) in Pittsfield, Mass. The Berkshire County Chamber of Commerce and Del Alba Realty promptly donate 20 acres of real estate for the rink.

Soon, a local printer, Quality Printing, donates $25,000. Berkshire Life Insurance gives $75,000. The Berkshire County sheriff's department gives $20,000 more, and USA Hockey donates another ten grand. The Connallys raise $250,000 in $10-a-plate potluck dinners, bake sales and skateathon pledges. And though they remain nearly $7 million shy of their $8 million goal, they plan to break ground this summer, on faith and borrowed money. "If we dig it," Steve says of corporate donors, "they will come."

The Connallys' foundation is called Quinn's Legacy, but of course Quinn's legacy already exists -- in the seven adults to whom he has given life, including the man from Marlborough, Mass., who tells the Connallys that the damnedest thing has happened since he got Quinn's kidney: His feet have grown two full sizes.

As for Quinn's heart, it now beats inside a 32-year-old black man in Kentucky, rendering racism rather ridiculous to the Connallys. "He's about to be married," says Steve Connally, his eyes slick as twin sheets of Zambonied ice. He looks as proud as a father could be. As of course he should.

Issue date: May 12, 2003

Sports Illustrated senior writer Steve Rushin pens the weekly Air and Space column in the magazine.

"A gentle giant," says his uncle Paul Chojnowski. Quinn has hands like a grown man's and an athlete's body that's been -- says his mother, Ann -- "sculpted and defined since age five." And so she develops the reverse concern of most hockey moms: Ann worries that her son will hurt someone else's child on the ice.

Quinn is smart -- in the 93rd percentile for IQ -- and maintains a B average at St. Stanislaus Kostka school in Adams, Mass. Anything lower and Steve won't let him play hockey. Never mind that Quinn was diagnosed with dyslexia in second grade and often asks, angrily and with deep frustration, "Why can't I read?"

His friends all devour the same books, and one evening Quinn announces that he intends to tackle an inch-thick Harry Potter. "So we laid belly-down, shoulder-to-shoulder, on his bed," says Ann. "And he started to read this long passage." It was like watching a high-wire act, and when Quinn, with scarcely a stumble, made it safely to the other side, he exhaled mightily and looked up from the page. For a long moment, says his mother, "We just looked at each other with these big smiles. Then Quinn said, 'O.K., Mom, I'm tired now.'" And he retired for the night.

Quinn is disconsolate if his father forgets to wake him for the 5 a.m. SportsCenter. The Connallys' front yard in Cheshire, Mass., is a lawn mower's minefield of Day-Glo pucks, golf balls, tennis balls and badminton birdies. After fracturing his right hand playing hockey, Quinn uses the cast as a paddle when playing Ping Pong in the backyard.

Quinn plays hockey like he reads Harry Potter. Slowly, yes, and without natural aptitude, but with such a doggedly competitive streak that after two seasons of tryouts he makes the MassConn Braves traveling team. Seldom has the phrase "traveling team" been so apt. The home rink is 70 minutes away, and it's not unusual for the family to travel six hours round-trip for a one-hour hockey game.

Thus a 75-minute drive to practice in Springfield is nothing. Or rather, it's something. Quinn does homework by domelight while Dad drives. "Real bonding time," Steve says of those rides.

At practice in the Springfield Civic Center, Quinn, a defenseman, slides to block a shot in a three-on-two drill. It is 6:15 p.m. when the puck strikes him in the back of the neck, just below the helmet. Steve hears another father say, "That didn't look good," and indeed, Quinn is taken to Bay State Medical Center, where his parents, and his teammates -- and their parents -- stay all night. "Hockey parents have a special connection," says Uncle Paul. "Maybe it's all those 5 a.m. ice times."

At 11:59 the next morning, the Connallys are told, unfathomably, that their son has died of a severed blood vessel. When they're asked, in the same breath, if they would be willing to donate Quinn's organs, the Connallys say, "Of course."

Quinn's death -- on Dec. 4, 2000 -- is reported as the first of its kind in youth hockey history. The Connallys receive cards from strangers in every one of the 50 states.

For two years Ann cannot enter an ice arena, and to this day she cannot bear to look at a Pee Wee-aged player. "With the big bag and stick?" she says. "Can't do it."

So it is astonishing that Ann should quit her job in retail management, and that Steve should leave his job as a "computer geek," to devote their working lives to one purpose: building a two-rink arena (and community/tutoring center) in Pittsfield, Mass. The Berkshire County Chamber of Commerce and Del Alba Realty promptly donate 20 acres of real estate for the rink.

Soon, a local printer, Quality Printing, donates $25,000. Berkshire Life Insurance gives $75,000. The Berkshire County sheriff's department gives $20,000 more, and USA Hockey donates another ten grand. The Connallys raise $250,000 in $10-a-plate potluck dinners, bake sales and skateathon pledges. And though they remain nearly $7 million shy of their $8 million goal, they plan to break ground this summer, on faith and borrowed money. "If we dig it," Steve says of corporate donors, "they will come."

The Connallys' foundation is called Quinn's Legacy, but of course Quinn's legacy already exists -- in the seven adults to whom he has given life, including the man from Marlborough, Mass., who tells the Connallys that the damnedest thing has happened since he got Quinn's kidney: His feet have grown two full sizes.

As for Quinn's heart, it now beats inside a 32-year-old black man in Kentucky, rendering racism rather ridiculous to the Connallys. "He's about to be married," says Steve Connally, his eyes slick as twin sheets of Zambonied ice. He looks as proud as a father could be. As of course he should.

Issue date: May 12, 2003

Sports Illustrated senior writer Steve Rushin pens the weekly Air and Space column in the magazine.