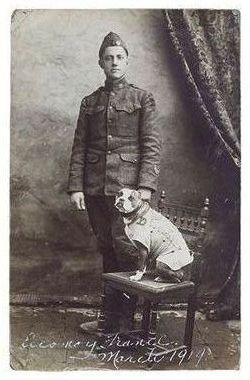

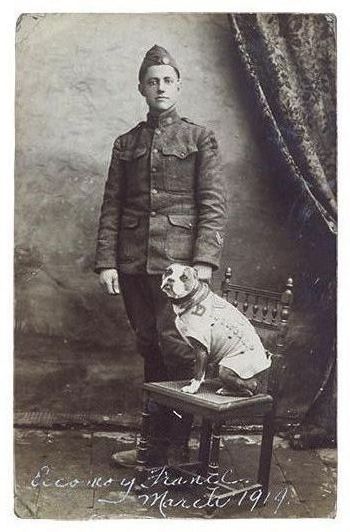

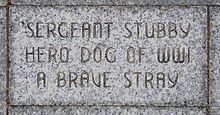

World War I Canine Military Hero, College Football Mascot. He was America's first canine hero gaining this distinction during military service in France doing World War I. Little is known about the scrawny stray puppy, a brown and white American pit bull terrier, until during mobilization of Connecticut National Guard units for deployment to Europe at the start of World War. He simply wandered into their encampment at Yale University in 1916 attaching himself to Private James Robert Conroy. The men were enamored by the animal and he soon became the Official mascot. The unit became the 102nd Infantry Regiment and shipped out for France aboard the troop ship S.S. Minnesota and with them the bull terrier, now known as Stubby, because of his short tail, having been smuggled on the ship in Private Conroy's overcoat. The young pit bull was oblivious to the noise of battle and quickly began to prove his mettle. For eighteen months, Stubby carried messages under fire, stood sentry duty and helped paramedics find the wounded in "no man's land." He gave early warning of deadly gas attacks and then a little gas mask fashioned by the men of the 102nd was affixed. He found and helped capture a German spy who was mapping a layout of the Allied trenches. He received the honorary rank of Sergeant for his actions. When seriously wounded by shrapnel, he was sent to the Red Cross hospital for surgery. Once recovered, he was given the Purple Heart and promptly returned to his regiment for duty. After the battle for the French village of Domremy, news of the little dog's heroism became known to the townspeople. The women prepared a hand-sewn chamois coat decorated with Allied flags and his name stitched in gold thread. The coat became his recognized trademark, becoming a depository for his service chevrons, medals, pins and buttons which he wore at parades for the rest of his life. In the post war, Stubby literally led the "good dogs life." Starting with a Victory Parade in France, as the 102nd passed in review, the little dog in the lead, stopped, raising his right paw to his face and giving his trademark salute, taught to him by regimental members, to a delighted President Woodrow Wilson in the reviewing stand. He was made a lifetime member of the American legion and marched in every legion parade and attended every legion convention from the end of the war until his death. He met three presidents of the United States, Wilson, Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge and was a lifetime member of the Red Cross and YMCA where he stayed frequently while being fed royally. He regularly hit the campaign trail, recruiting members for the American Red Cross and selling victory bonds. He was personally decorated for valor by General John J. Pershing in a post-war ceremony with a gold hero dog's medal that was commissioned by the Humane Society. The Plush Grand Hotel Majestic in New York City lifted its ban on dogs and Stubby stayed there many times en route from John Conroy's residence in New Briton, Connecticut, to one of many visits to Washington. In 1921, Conroy along with Stubby, headed to Georgetown to enroll in law school. The dog became a practicing Hoya serving several terms as mascot to the football team. Between halves, the dog would nudge a football around the field with his nose, to the delight of the crowd. His performance is deemed the inspiration which started elaborate half time shows at football games across the country. Stubby spent his final years with John Conroy, his acknowledged master, who had rescued him so many years ago. Upon his death on April 4 in the arms of John, from symptoms of a very old dog, the remains were preserved with technical assistance from the Smithsonian Institution. Then Stubby, his medals and personal effects were donated to the Smithsonian and then loaned with his medal-encrusted blanket to the National Red Cross Museum where the mounting was displayed for years. Stubby became shabby and the preservation was returned in 1956 to the Smithsonian where it was placed in storage. It was resurrected a few years ago, refurbished and loaned to the State of Connecticut which featured the war hero at a statewide dog show. He is now on temporary display in the Hartford Armory, Hartford, Connecticut. Legacy...The bull terrier's fame was recaptured on April 1, 2001 when he was featured prominently, his photo on the cover and a story inside about military dogs in "Parade" the Sunday insert magazine placed in leading newspapers across America. In 1978, he was the subject of a children's book titled "Stubby: Brave Soldier Dog." The bravery, loyalty and military usefulness of Stubby was instrumental in the creation of the U.S. "K9 Corps" during World War II. In 1925, he had his portrait painted by Charles Ayer Whipple who was the artist to the capital in Washington, D.C. and currently hangs in the 102nd Regimental Museum in New Haven. He tried his paw in show business appearing in a series of vaudeville shows during 1919 with Mary Pickford.

World War I Canine Military Hero, College Football Mascot. He was America's first canine hero gaining this distinction during military service in France doing World War I. Little is known about the scrawny stray puppy, a brown and white American pit bull terrier, until during mobilization of Connecticut National Guard units for deployment to Europe at the start of World War. He simply wandered into their encampment at Yale University in 1916 attaching himself to Private James Robert Conroy. The men were enamored by the animal and he soon became the Official mascot. The unit became the 102nd Infantry Regiment and shipped out for France aboard the troop ship S.S. Minnesota and with them the bull terrier, now known as Stubby, because of his short tail, having been smuggled on the ship in Private Conroy's overcoat. The young pit bull was oblivious to the noise of battle and quickly began to prove his mettle. For eighteen months, Stubby carried messages under fire, stood sentry duty and helped paramedics find the wounded in "no man's land." He gave early warning of deadly gas attacks and then a little gas mask fashioned by the men of the 102nd was affixed. He found and helped capture a German spy who was mapping a layout of the Allied trenches. He received the honorary rank of Sergeant for his actions. When seriously wounded by shrapnel, he was sent to the Red Cross hospital for surgery. Once recovered, he was given the Purple Heart and promptly returned to his regiment for duty. After the battle for the French village of Domremy, news of the little dog's heroism became known to the townspeople. The women prepared a hand-sewn chamois coat decorated with Allied flags and his name stitched in gold thread. The coat became his recognized trademark, becoming a depository for his service chevrons, medals, pins and buttons which he wore at parades for the rest of his life. In the post war, Stubby literally led the "good dogs life." Starting with a Victory Parade in France, as the 102nd passed in review, the little dog in the lead, stopped, raising his right paw to his face and giving his trademark salute, taught to him by regimental members, to a delighted President Woodrow Wilson in the reviewing stand. He was made a lifetime member of the American legion and marched in every legion parade and attended every legion convention from the end of the war until his death. He met three presidents of the United States, Wilson, Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge and was a lifetime member of the Red Cross and YMCA where he stayed frequently while being fed royally. He regularly hit the campaign trail, recruiting members for the American Red Cross and selling victory bonds. He was personally decorated for valor by General John J. Pershing in a post-war ceremony with a gold hero dog's medal that was commissioned by the Humane Society. The Plush Grand Hotel Majestic in New York City lifted its ban on dogs and Stubby stayed there many times en route from John Conroy's residence in New Briton, Connecticut, to one of many visits to Washington. In 1921, Conroy along with Stubby, headed to Georgetown to enroll in law school. The dog became a practicing Hoya serving several terms as mascot to the football team. Between halves, the dog would nudge a football around the field with his nose, to the delight of the crowd. His performance is deemed the inspiration which started elaborate half time shows at football games across the country. Stubby spent his final years with John Conroy, his acknowledged master, who had rescued him so many years ago. Upon his death on April 4 in the arms of John, from symptoms of a very old dog, the remains were preserved with technical assistance from the Smithsonian Institution. Then Stubby, his medals and personal effects were donated to the Smithsonian and then loaned with his medal-encrusted blanket to the National Red Cross Museum where the mounting was displayed for years. Stubby became shabby and the preservation was returned in 1956 to the Smithsonian where it was placed in storage. It was resurrected a few years ago, refurbished and loaned to the State of Connecticut which featured the war hero at a statewide dog show. He is now on temporary display in the Hartford Armory, Hartford, Connecticut. Legacy...The bull terrier's fame was recaptured on April 1, 2001 when he was featured prominently, his photo on the cover and a story inside about military dogs in "Parade" the Sunday insert magazine placed in leading newspapers across America. In 1978, he was the subject of a children's book titled "Stubby: Brave Soldier Dog." The bravery, loyalty and military usefulness of Stubby was instrumental in the creation of the U.S. "K9 Corps" during World War II. In 1925, he had his portrait painted by Charles Ayer Whipple who was the artist to the capital in Washington, D.C. and currently hangs in the 102nd Regimental Museum in New Haven. He tried his paw in show business appearing in a series of vaudeville shows during 1919 with Mary Pickford.

Bio by: Donald Greyfield

Advertisement