Paternal Grandfather on FAG

Paternal Grandmother on FAG

====================================

SOURCE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lynching_of_Laura_and_L._D._Nelson

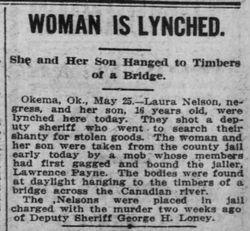

Laura and L. D. Nelson were an African-American mother and son who were lynched on May 25, 1911, near Okemah, Okfuskee County, Oklahoma.[1][2] They had been seized from their cells in the Okemah county jail the night before by a group of up to 40 white men, reportedly including Charley Guthrie, father of the folk singer Woody Guthrie.[3] The Associated Press reported that Laura was raped.[a] She and L. D. were then hanged from a bridge over the North Canadian River. According to one source, Laura had a baby with her who survived the attack.[5]

Laura and L. D. were in jail because L. D. had been accused of having shot and killed Deputy Sheriff George H. Loney of the Okfuskee County Sherriff's Office,[6] during a search of the Nelsons' farm for a stolen cow. L. D. and Laura were both charged with murder; Laura was charged because she allegedly grabbed the gun first. Her husband, Austin, pleaded guilty to larceny and was sent to the relative safety of the state prison in McAlester, while his wife and son were held in the county jail until their trial.[7][8]

Sightseers gathered on the bridge on the morning of the lynching. George Henry Farnum, the owner of Okemah's only photography studio, took photographs, which were distributed as postcards, a common practice at the time.[9] Although the district judge convened a grand jury, the killers were never identified.[10] Four of Farnum's photographs are known to have survived—two spectator scenes and one close-up view each of L. D. and Laura. Three of the images were published in 2000 and exhibited at the Roth Horowitz Gallery in New York by James Allen, an antique collector.[11] The images of Laura Nelson are the only known surviving photographs of a black female lynching victim.[12][13]

==========================================================

SOURCE: https://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/may/24

May 24, 1911

White Mob in Oklahoma Abducts and Lynches Laura Nelson and Her Young Son

On May 24, 1911, shortly before midnight, a mob of dozens of armed white men broke into the Okfuskee County jail in Okemah, Oklahoma, and abducted Laura Nelson and her young son, L.D. The mob took the Black woman and boy six miles away and hanged them from a bridge over the Canadian River, close to the Black part of town; according to some reports, members of the mob also raped Mrs. Nelson, who was about 28 years old according to census records, before lynching her alongside her son. Their bodies were found the next morning.

A few weeks before, local police had reportedly come to the Nelsons' cabin and accused Mr. Nelson of stealing meat. When a white deputy sheriff was shot and killed while searching the cabin, Mrs. Nelson and L.D.—who was reported as 14-16 years old in news reports, but was more likely just 12 years old according to census records—were accused of killing him. The entire Nelson family was arrested and jailed after the deputy's shooting, and some reports indicate that a 2-year-old daughter—listed as Carry Nelson in the 1910 census—was also with Mrs. Nelson in jail.

The prosecution's presentation at the preliminary hearing raised doubts about whether the State had sufficient evidence for a conviction. Many Black people were lynched across the U.S. under accusations of murder or assault. During this era of racial terror, mere suggestions of Black-on-white violence could provoke mob violence and lynching. Though these communities had developed and functioning judicial systems, white defendants were more likely to face trial while Black people regularly suffered death at the hands of a violent mob, without trial or any opportunity to present evidence of innocence or self defense. In this case, after Laura and L.D. Nelson were lynched, it was revealed that they claimed to have shot the deputy as he reached for his gun and seemed about to shoot Mr. Nelson, unprovoked.

Before any trial could take place, however, newspaper accounts sensationalized the case, misreporting the mother's and son's ages and presuming their guilt. Press reports described Laura Nelson as "very small of stature, very black, about thirty-five years old and vicious," while L.D. was described as "slender and tall, yellow and ignorant" and "raged."

By the night of the lynching, Mrs. Nelson's husband and L.D.'s father—whose first name is reported as Oscar or Austin in surviving records—had already been convicted of a lesser offense, sentenced to a prison term, and sent to the penitentiary; he was not present to defend his family against the mob. Unconfirmed reports vary regarding the fate of the Nelsons' young daughter; some claim she was found drowned in the river, while others claim she was found alive and taken in to be raised by a local Black family.

After a Black boy reportedly found Laura Nelson's and L.D. Nelson's hanging corpses at the bridge the next morning, hundreds of white people from Okemah came to view the bodies. Some even posed on the bridge to have their photos taken with the bodies of the dead Black woman and boy. Those photographs were later reprinted as postcards and sold at novelty stores.

The mob's choice to deprive the Nelsons of their basic rights to due process, and hang them on a bridge frequented by Black people and near where many local Black residents lived, was meant to maintain white supremacy by sending a message of terror and intimidation to the entire Black community. "While the general sentiment is adverse to the method," the Okemah Ledger wrote a day after the lynchings, "it is generally thought that the negroes got what would have been due them." Even proceedings supposedly held to investigate the Nelsons' deaths were steeped in racism; when a special grand jury was called to investigate the lynching, the district judge instructed the white jurors to be mindful of their duty as members "of a superior race and greater intelligence to protect this weaker race." No one was indicted, prosecuted, or held legally accountable for lynching Laura and L.D. Nelson.

Mrs. Nelson and her son were two of at least 75 documented victims of racial terror lynching that took place in Oklahoma between 1877 and 1950, and they are among more than 6,500 victims of racial terror lynching that EJI has documented between 1865 and 1950. To learn more, explore EJI's reports, Lynching in America and Reconstruction in America.

Paternal Grandfather on FAG

Paternal Grandmother on FAG

====================================

SOURCE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lynching_of_Laura_and_L._D._Nelson

Laura and L. D. Nelson were an African-American mother and son who were lynched on May 25, 1911, near Okemah, Okfuskee County, Oklahoma.[1][2] They had been seized from their cells in the Okemah county jail the night before by a group of up to 40 white men, reportedly including Charley Guthrie, father of the folk singer Woody Guthrie.[3] The Associated Press reported that Laura was raped.[a] She and L. D. were then hanged from a bridge over the North Canadian River. According to one source, Laura had a baby with her who survived the attack.[5]

Laura and L. D. were in jail because L. D. had been accused of having shot and killed Deputy Sheriff George H. Loney of the Okfuskee County Sherriff's Office,[6] during a search of the Nelsons' farm for a stolen cow. L. D. and Laura were both charged with murder; Laura was charged because she allegedly grabbed the gun first. Her husband, Austin, pleaded guilty to larceny and was sent to the relative safety of the state prison in McAlester, while his wife and son were held in the county jail until their trial.[7][8]

Sightseers gathered on the bridge on the morning of the lynching. George Henry Farnum, the owner of Okemah's only photography studio, took photographs, which were distributed as postcards, a common practice at the time.[9] Although the district judge convened a grand jury, the killers were never identified.[10] Four of Farnum's photographs are known to have survived—two spectator scenes and one close-up view each of L. D. and Laura. Three of the images were published in 2000 and exhibited at the Roth Horowitz Gallery in New York by James Allen, an antique collector.[11] The images of Laura Nelson are the only known surviving photographs of a black female lynching victim.[12][13]

==========================================================

SOURCE: https://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/may/24

May 24, 1911

White Mob in Oklahoma Abducts and Lynches Laura Nelson and Her Young Son

On May 24, 1911, shortly before midnight, a mob of dozens of armed white men broke into the Okfuskee County jail in Okemah, Oklahoma, and abducted Laura Nelson and her young son, L.D. The mob took the Black woman and boy six miles away and hanged them from a bridge over the Canadian River, close to the Black part of town; according to some reports, members of the mob also raped Mrs. Nelson, who was about 28 years old according to census records, before lynching her alongside her son. Their bodies were found the next morning.

A few weeks before, local police had reportedly come to the Nelsons' cabin and accused Mr. Nelson of stealing meat. When a white deputy sheriff was shot and killed while searching the cabin, Mrs. Nelson and L.D.—who was reported as 14-16 years old in news reports, but was more likely just 12 years old according to census records—were accused of killing him. The entire Nelson family was arrested and jailed after the deputy's shooting, and some reports indicate that a 2-year-old daughter—listed as Carry Nelson in the 1910 census—was also with Mrs. Nelson in jail.

The prosecution's presentation at the preliminary hearing raised doubts about whether the State had sufficient evidence for a conviction. Many Black people were lynched across the U.S. under accusations of murder or assault. During this era of racial terror, mere suggestions of Black-on-white violence could provoke mob violence and lynching. Though these communities had developed and functioning judicial systems, white defendants were more likely to face trial while Black people regularly suffered death at the hands of a violent mob, without trial or any opportunity to present evidence of innocence or self defense. In this case, after Laura and L.D. Nelson were lynched, it was revealed that they claimed to have shot the deputy as he reached for his gun and seemed about to shoot Mr. Nelson, unprovoked.

Before any trial could take place, however, newspaper accounts sensationalized the case, misreporting the mother's and son's ages and presuming their guilt. Press reports described Laura Nelson as "very small of stature, very black, about thirty-five years old and vicious," while L.D. was described as "slender and tall, yellow and ignorant" and "raged."

By the night of the lynching, Mrs. Nelson's husband and L.D.'s father—whose first name is reported as Oscar or Austin in surviving records—had already been convicted of a lesser offense, sentenced to a prison term, and sent to the penitentiary; he was not present to defend his family against the mob. Unconfirmed reports vary regarding the fate of the Nelsons' young daughter; some claim she was found drowned in the river, while others claim she was found alive and taken in to be raised by a local Black family.

After a Black boy reportedly found Laura Nelson's and L.D. Nelson's hanging corpses at the bridge the next morning, hundreds of white people from Okemah came to view the bodies. Some even posed on the bridge to have their photos taken with the bodies of the dead Black woman and boy. Those photographs were later reprinted as postcards and sold at novelty stores.

The mob's choice to deprive the Nelsons of their basic rights to due process, and hang them on a bridge frequented by Black people and near where many local Black residents lived, was meant to maintain white supremacy by sending a message of terror and intimidation to the entire Black community. "While the general sentiment is adverse to the method," the Okemah Ledger wrote a day after the lynchings, "it is generally thought that the negroes got what would have been due them." Even proceedings supposedly held to investigate the Nelsons' deaths were steeped in racism; when a special grand jury was called to investigate the lynching, the district judge instructed the white jurors to be mindful of their duty as members "of a superior race and greater intelligence to protect this weaker race." No one was indicted, prosecuted, or held legally accountable for lynching Laura and L.D. Nelson.

Mrs. Nelson and her son were two of at least 75 documented victims of racial terror lynching that took place in Oklahoma between 1877 and 1950, and they are among more than 6,500 victims of racial terror lynching that EJI has documented between 1865 and 1950. To learn more, explore EJI's reports, Lynching in America and Reconstruction in America.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement