Krall, 18, became homeless in the summer of 2009 when his aunt and uncle, with whom he lived, were evicted from their apartment in Brea. His aunt went to stay in a women's shelter. His uncle slept in his pickup truck. It's not known where John slept. "He said he had a lot of hiding spots ... he said he had a foxhole out there in the Brea hills," said his uncle.

On New Year's Eve, at about 6:30 p.m., John was seen by a Brea police officer standing in the road near State College Boulevard and Birch Street, trying to stop traffic. He told the officer that he'd taken more than 100 sleeping pills and made statements to the effect of wanting to hurt himself. The officer called the Fire Department, which took Krall to St. Jude Medical Center in Fullerton. Later that evening, the hospital called Fullerton police to say that Krall had walked away. He was later found at a Denny's restaurant on Imperial Highway by the same Brea police officer who'd dealt with him earlier. Again the Brea Fire Department was called, and again Krall was taken to St. Jude's. And again he walked away. Again the police searched for him. By the time they found him, shortly before 8 a.m. on New Year's Day, he was dead

John Krall's mother killed a man.

On July 15, 1999, Andrea Jean Krall fatally shot her boyfriend, Elijah Johnson, in the back of the head while he slept in a Motel 6 in Hacienda Heights. At her trial the following year, her attorney said she was the victim of battered women's syndrome. The jury, however, convicted her of second degree murder, not the lesser charge of voluntary manslaughter her attorney had sought. Before she was sentenced, Andrea Krall asked the judge for a leniency, saying she hoped to remain a mother to her five children, but the judge ordered her, then 38, to serve 40 years to life. On Nov. 19, 2004, she committed suicide at Central California Women's Facility in Chowchilla, said Terry Thornton, a spokeswoman for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. John, who had a different father than Krall's four other children, went into foster care, said John's uncle. Later, he and his wife, Andrea Krall's sister – took John to live with them in Brea.

A Talent For Art

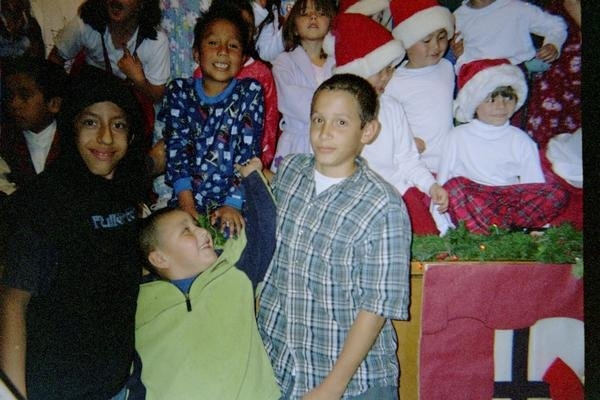

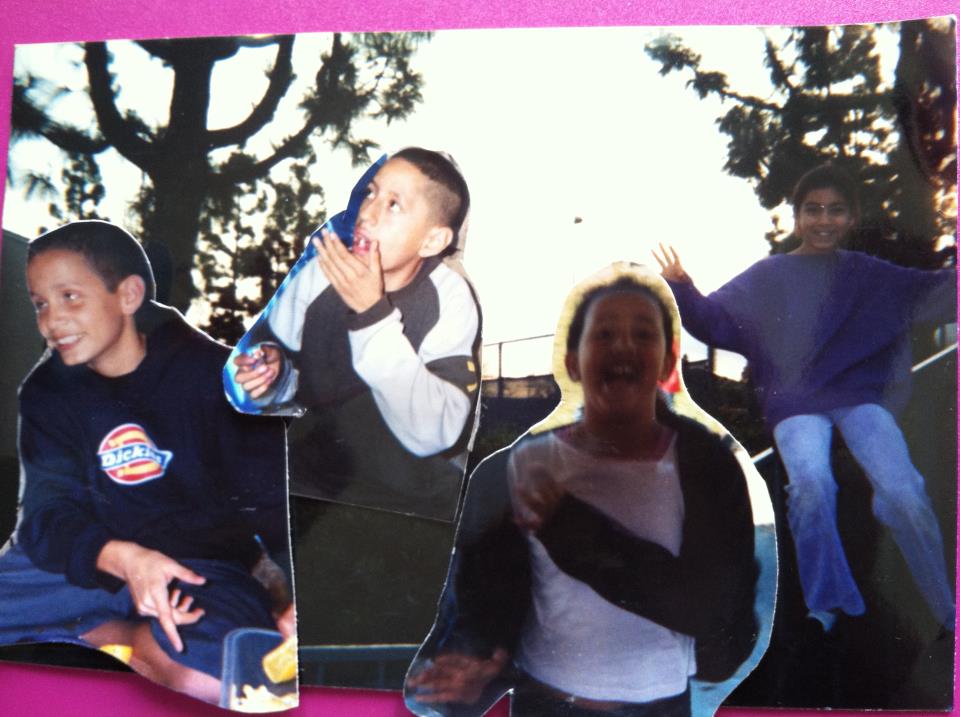

A former Brea neighbor, Jayni, said John was "a sweet, sensitive, good kid." - "Every time I'd give him something he'd be so appreciative for any little thing, like when I would give him spaghetti or he'd come over and get brownies," she said. The first time they met, about three years ago, John asked her about her son who had died a few years earlier after a bone-marrow transplant. "He showed a lot of concern, asked how it happened. ... He tried to comfort me." John had a talent for drawing. A school friend, Jonathan, said the two used to create video games together using a computer program. "He was always good and drawing and art, and I was the brains," his friend wrote. "We'd stay up all night (not sleeping until about 5 a.m.) making and playing video games ... We both knew we were nerds, but we didn't care." John's half brother, Tony, said, "If Johnny wanted to be remembered for anything, I think it would be his art."

Mental Illness

There's a history of schizophrenia in Krall's family, the uncle said. "Now that I look back at last year, I can piece things together, and it occurred to me that John was maybe developing schizophrenia. He let go of personal hygiene, financial values, monetary values ... He just kind of let those things go." John would wave his arms and talk to himself, Jayni said. "Six months before they moved out, you could see a huge decline in him," she said. "Everybody noticed it." On June 29, John fought with his uncle and damaged the apartment. He was arrested and spent time in jail. He pleaded guilty on July 10 to misdemeanor assault and battery and was sentenced to time served plus three years probation, court records show. By the time he got out of jail, he didn't have a home to go back to. His uncles tile-setting business had not fared well in the recession. He was living in his pickup truck. "Being homeless, to be honest with you, was self inflicted," the uncle said. "I didn't make enough money." On Christmas Day, Jayni felt she had to go look for John. She found him in front of a Rite Aid on Imperial Highway, eating Mexican food from a garbage can. She bought him a couple of cheeseburgers and told him to stay put while she went to get money for a motel room. When she came back, he was gone. "When I saw him on Christmas, even though I could tell he wasn't connected anymore ... he still had that sweet, sensitive way about him," she said. "I think there were moments when he was OK, and then he would not be OK."

Dead By The Tracks

Friends and relatives say that somebody – the police or the hospital – should have made sure John didn't walk away, especially after he'd been brought back once. "They should have never let him out of their sight," the uncle said. "He would still be alive today." "It's just like everybody let that kid down," Jayni said. A hospital spokesperson said the hospital has no authority to hold patients against their will. "Legally, a patient may leave our hospital at any time," she said. The Brea police can't afford to take an officer out of the field to stay with a patient at the hospital, they said. "If doctors are going to admit him for medical treatment, we don't know how long he's going to be there,". Fullerton police have might have handled such a situation differently. They would retain custody of a person who needed to be evaluated for a psychiatric hold, often referred to as a "5150" for the section of the California Welfare and Institutions Code that covers it. "If somebody is to be evaluated and they were in our custody, we would need to maintain custody of that person," said a spokesman from the Fullerton police. However, Krall was never in custody of the Brea police, they said. The Brea Fire Department took him to the hospital both times, while the police officer went along to see that he was admitted.

At 7:49 a.m. on Jan. 1, Fullerton police got a call about a body next to the railroad tracks under Harbor Boulevard north of Bastanchury Road. Some joggers and bikers on an adjacent trail had found John dead. A cause of death had not been determined.

John Krall is buried near his mother at Rose Hills Memorial Park in Whittier.

This article appeared in the Orange County Register. After the story ran, the readers of the paper generously donated money to buy a headstone to mark his grave.

Krall, 18, became homeless in the summer of 2009 when his aunt and uncle, with whom he lived, were evicted from their apartment in Brea. His aunt went to stay in a women's shelter. His uncle slept in his pickup truck. It's not known where John slept. "He said he had a lot of hiding spots ... he said he had a foxhole out there in the Brea hills," said his uncle.

On New Year's Eve, at about 6:30 p.m., John was seen by a Brea police officer standing in the road near State College Boulevard and Birch Street, trying to stop traffic. He told the officer that he'd taken more than 100 sleeping pills and made statements to the effect of wanting to hurt himself. The officer called the Fire Department, which took Krall to St. Jude Medical Center in Fullerton. Later that evening, the hospital called Fullerton police to say that Krall had walked away. He was later found at a Denny's restaurant on Imperial Highway by the same Brea police officer who'd dealt with him earlier. Again the Brea Fire Department was called, and again Krall was taken to St. Jude's. And again he walked away. Again the police searched for him. By the time they found him, shortly before 8 a.m. on New Year's Day, he was dead

John Krall's mother killed a man.

On July 15, 1999, Andrea Jean Krall fatally shot her boyfriend, Elijah Johnson, in the back of the head while he slept in a Motel 6 in Hacienda Heights. At her trial the following year, her attorney said she was the victim of battered women's syndrome. The jury, however, convicted her of second degree murder, not the lesser charge of voluntary manslaughter her attorney had sought. Before she was sentenced, Andrea Krall asked the judge for a leniency, saying she hoped to remain a mother to her five children, but the judge ordered her, then 38, to serve 40 years to life. On Nov. 19, 2004, she committed suicide at Central California Women's Facility in Chowchilla, said Terry Thornton, a spokeswoman for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. John, who had a different father than Krall's four other children, went into foster care, said John's uncle. Later, he and his wife, Andrea Krall's sister – took John to live with them in Brea.

A Talent For Art

A former Brea neighbor, Jayni, said John was "a sweet, sensitive, good kid." - "Every time I'd give him something he'd be so appreciative for any little thing, like when I would give him spaghetti or he'd come over and get brownies," she said. The first time they met, about three years ago, John asked her about her son who had died a few years earlier after a bone-marrow transplant. "He showed a lot of concern, asked how it happened. ... He tried to comfort me." John had a talent for drawing. A school friend, Jonathan, said the two used to create video games together using a computer program. "He was always good and drawing and art, and I was the brains," his friend wrote. "We'd stay up all night (not sleeping until about 5 a.m.) making and playing video games ... We both knew we were nerds, but we didn't care." John's half brother, Tony, said, "If Johnny wanted to be remembered for anything, I think it would be his art."

Mental Illness

There's a history of schizophrenia in Krall's family, the uncle said. "Now that I look back at last year, I can piece things together, and it occurred to me that John was maybe developing schizophrenia. He let go of personal hygiene, financial values, monetary values ... He just kind of let those things go." John would wave his arms and talk to himself, Jayni said. "Six months before they moved out, you could see a huge decline in him," she said. "Everybody noticed it." On June 29, John fought with his uncle and damaged the apartment. He was arrested and spent time in jail. He pleaded guilty on July 10 to misdemeanor assault and battery and was sentenced to time served plus three years probation, court records show. By the time he got out of jail, he didn't have a home to go back to. His uncles tile-setting business had not fared well in the recession. He was living in his pickup truck. "Being homeless, to be honest with you, was self inflicted," the uncle said. "I didn't make enough money." On Christmas Day, Jayni felt she had to go look for John. She found him in front of a Rite Aid on Imperial Highway, eating Mexican food from a garbage can. She bought him a couple of cheeseburgers and told him to stay put while she went to get money for a motel room. When she came back, he was gone. "When I saw him on Christmas, even though I could tell he wasn't connected anymore ... he still had that sweet, sensitive way about him," she said. "I think there were moments when he was OK, and then he would not be OK."

Dead By The Tracks

Friends and relatives say that somebody – the police or the hospital – should have made sure John didn't walk away, especially after he'd been brought back once. "They should have never let him out of their sight," the uncle said. "He would still be alive today." "It's just like everybody let that kid down," Jayni said. A hospital spokesperson said the hospital has no authority to hold patients against their will. "Legally, a patient may leave our hospital at any time," she said. The Brea police can't afford to take an officer out of the field to stay with a patient at the hospital, they said. "If doctors are going to admit him for medical treatment, we don't know how long he's going to be there,". Fullerton police have might have handled such a situation differently. They would retain custody of a person who needed to be evaluated for a psychiatric hold, often referred to as a "5150" for the section of the California Welfare and Institutions Code that covers it. "If somebody is to be evaluated and they were in our custody, we would need to maintain custody of that person," said a spokesman from the Fullerton police. However, Krall was never in custody of the Brea police, they said. The Brea Fire Department took him to the hospital both times, while the police officer went along to see that he was admitted.

At 7:49 a.m. on Jan. 1, Fullerton police got a call about a body next to the railroad tracks under Harbor Boulevard north of Bastanchury Road. Some joggers and bikers on an adjacent trail had found John dead. A cause of death had not been determined.

John Krall is buried near his mother at Rose Hills Memorial Park in Whittier.

This article appeared in the Orange County Register. After the story ran, the readers of the paper generously donated money to buy a headstone to mark his grave.

Gravesite Details

Seven graves to the left of John's is that of his mothers, Andrea.