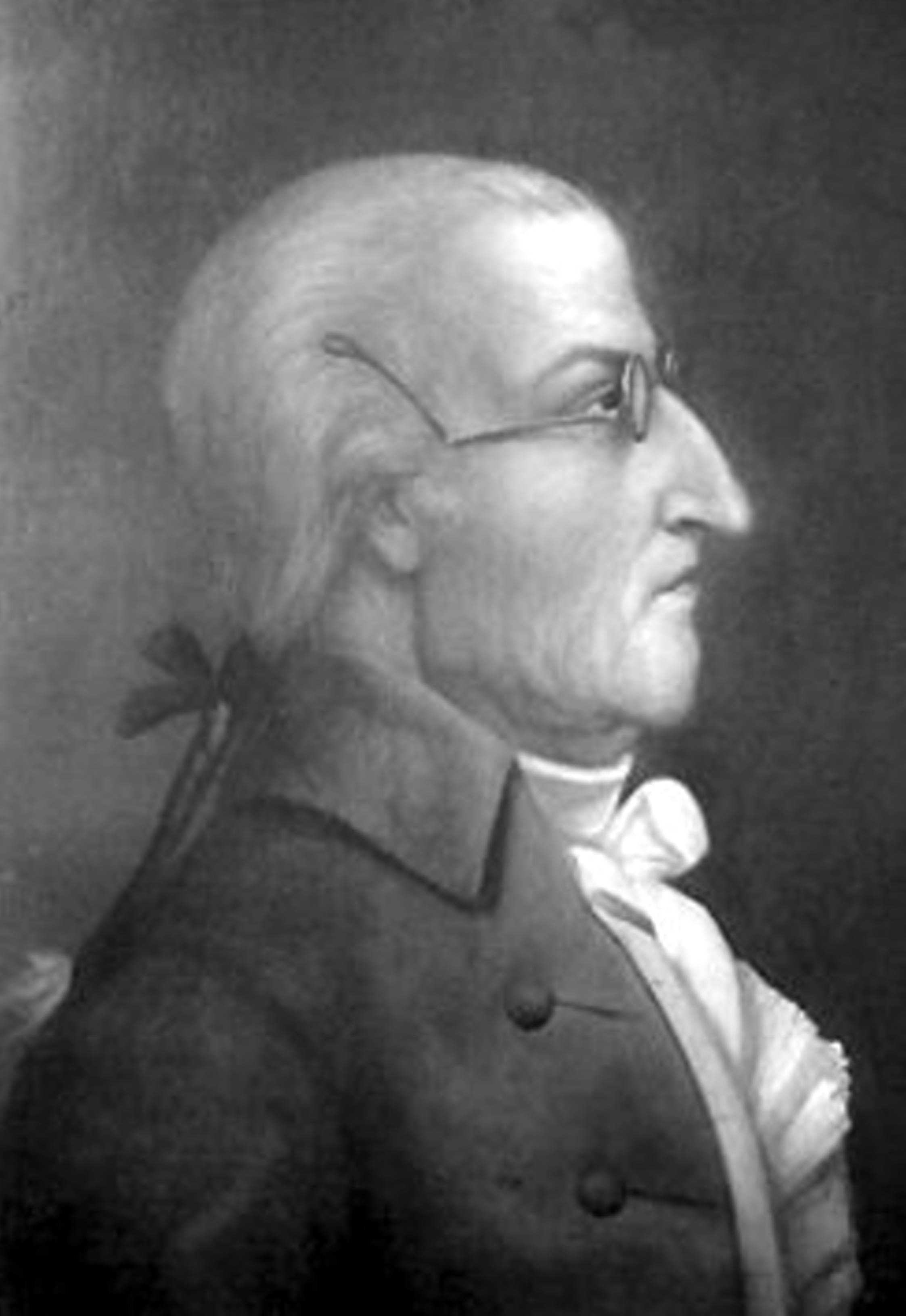

Trained in law at an early age by Andrew Hamilton, Benjamin Chew inherited his mentor's clients, the descendants of William Penn, including Thomas Penn (1702–1775) and his brother Richard Penn, Sr. (1706–1771), and their sons Governor John Penn (1729–1795), Richard Penn, Jr. (1734–1811), and John Penn (1760–1834). The Penn family was the basis of his private practice, and he represented them for six decades.

He had a lifelong personal friendship with George Washington, who is said to have treated Chew's children "as if they were his own." Chew lived and practiced law in Philadelphia four blocks from Independence Hall, and provided pro bono his knowledge of substantive law to America's Founding Fathers during the creation of the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights.

Benjamin Chew was the son of Samuel Chew, a physician and first Chief Justice of Delaware, and Mary Galloway Chew (1697–1734).

Chew took an interest in the field of law at an early age. In 1736, when he was 15 years old, he began to read law in the Philadelphia offices of the former Attorney General of Pennsylvania, Andrew Hamilton, then the speaker of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives. The year before, Hamilton had won a landmark case in American jurisprudence by his eloquent pro bono defense of the publisher Peter Zenger. It established the precedent of truth as an absolute defense against charges of libel.

Chew was strongly influenced by Hamilton's ideas about a free press, and also the reading materials which his mentor provided him, especially Sir Francis Bacon's Lawtracts. His understanding of English legal history, and especially the Charter of Liberties, enhanced by his later studies at London's Middle Temple, fostered Chew's enduring commitment to the civil liberties that are guaranteed by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, especially the right to free speech.

Following his father's death, Chew returned to Pennsylvania in 1744. He began to practice law in Dover, Delaware, while supporting his siblings and stepmother. Although Chew was raised in a Quaker family, he had first broken with Quaker tradition in 1741, when he agreed with his father, who had instructed a grand jury in Newcastle on the lawfulness of resistance to an armed force. In 1747, at age 25, Chew also went against Quaker tradition when he took the Oath of Attorney in Pennsylvania.

Chew moved to Philadelphia in 1754. He continued his legal responsibilities in both Delaware and Pennsylvania for the rest of his life. After early appointments in the Quaker-dominated government, following his second marriage he went into private practice in 1757; the following year joined the Anglican Church. He was taking a separate path to influence outside the Quaker elite. In 1758, Chew left the Quakers permanently and joined the Church of England.

Chew was highly effective in defending civil liberties and settling boundary disputes; he represented the descendants of William Penn and their proprietorship, the largest landholders in Pennsylvania, for more than 60 years. In 1757 Chew entered private practice: he derived most of his income from that, managing his second wife's considerable estate, and collecting quit-rents from his various properties. Chew continued the family practice of investing in land in the American colonies until the end of his life, expanding their holdings in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and New Jersey.

In 1771, Chew purchased the former house of his client, Governor John Penn, on South Third Street; Penn had returned to England to settle his father's (Richard Penn, Sr.) estate. The Chews entertained many visiting dignitaries, such as John Penn, Tench Francis, Jr., Robert, Thomas, and Samuel Wharton, Thomas Willing, John Cadwalader, Chief Justice William Allen and his wife Margaret, daughter of Andrew Hamilton, Dr. William Smith, Provost of the College of Philadelphia, botanist John Bartram, Edward Shippen, III, Edward Shippen, IV, and Peggy Shippen, Thomas Mifflin, later to become Governor of Pennsylvania, and Brigadier General Henry Bouquet, hero of the French and Indian War.

Abigail Adams referred to Chews' daughters as part of a "constellation of beauties" in Philadelphia. Margaret Chew (1760–1824) married Maryland Governor John E. Howard in 1787. Sophia (1769–1841) was invited to attend Martha Washington's first public event in Philadelphia. Harriet (1775–1861) was asked to entertain George Washington while his portrait was being painted. In 1800, she married the only son of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, signer of the Declaration of Independence, who built Homewood for them as a wedding gift. Throughout the Revolutionary War, George Washington aided the transfer of letters between Mr. and Mrs. Chew, during months when they were forced to live apart.

On August 4, 1777, the Executive Committee of the Continental Congress decided to place Chew in preventive detention in New Jersey. After Chew was released from parole in May 1778, he decided to move his family to Whitehall, their estate in Delaware, to buffer them from the political turbulence of Philadelphia. While in Delaware, the Chews rented their house on Third Street to Don Juan de Miralles (the Spanish representative to the American government); the Marquis de Chastellux (principal liaison officer between the French Commander-in-Chief and George Washington); and to George and Martha Washington, from November 1781 to March 1782, during the Second Continental Congress.

By 1783, the Chews concluded that the political situation was safe enough for their family to return to Philadelphia. They lived full-time in the house on South Third Street during the formation of the United States: the Constitutional Convention; the Congress of the Confederation; and in 1792, the official adoption of the Bill of Rights by the First United States Congress.

Benjamin Chew was Speaker of the Lower House for the Delaware counties (1753–1758); Attorney General and member of the Council of Pennsylvania (1754–1769); Recorder of Philadelphia City (1755–1774); Master of Rolls (1755–1774); and Provincial Councillor of Pennsylvania (1755).

In 1757 he began private practice, which was his chief pursuit for years, somewhat reducing his political appointments in the Quaker government. That year, he was also elected a trustee of The Academy and College of Philadelphia (the origins of the University of Pennsylvania) and continued as such until 1791. He also taught numerous law students. Foremost among Benjamin Chew's law students were Brigade Major Edward Tilghman and Judge William Tilghman. "These Tilghmans were so successful in the law that they were both offered the post of State Chief Justice in 1805."

He was selected as a Commissioner of Philadelphia (1761); appointed as Register-General of Wills (1765–1777); and as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania (1774–1777). During the American Revolutionary War, the Executive Council governing the new state removed him from office in 1777 and kept him in preventive detention in New Jersey until after the British forces left the Philadelphia region.

After the war, Chew resumed a position of influence in the new society and, eventually, its government. He was appointed as Judge and President of the High Court of Errors and Appeals (1791–1808).

After the state and national governments had been formed, in 1791, Chew was appointed by Thomas Mifflin, Pennsylvania's first Governor and the former President of the Continental Congress, to preside as the President over Pennsylvania's first High Court of Errors and Appeals. He held the position until he retired in 1808.

Prior to the American Revolution, Chew was friends with both George Washington and John Adams, and was a strong advocate for the colonies. As a lifelong pacifist, however, Chew believed that protest and reform were necessary to resolve the ongoing American conflicts with the British Parliament. Having been born and reared as a Quaker, he did not support active revolution. He maintained that position although he had left the Quakers and joined the Anglican Church in 1758. Early in the conflict, both the British and colonial sides claimed his allegiance since Chew had such a visible position in the colony and played so many important roles.

Chew was undecided about the correct course to take. "I have stated that an opposition of force of arms to the lawful authority of the king or his ministries…is high treason, but in the moment when the king or his ministries shall exceed the constitutional authority vested in them … submission to their mandates becomes treason." -Benjamin Chew, Chief Justice of Pennsylvania, in an address to the last provincial grand jury, April 10, 1776

On August 4, 1777, when General Howe and the British army were nearing Philadelphia, the Executive Council of the new government "issued a warrant for (Chew's) arrest on grounds of protecting the public safety. The Executive Council of the Continental Congress decided at the last minute against allowing Chew to remain at his home near Philadelphia. For his own safety, they decided to allow both Chew and the Governor John Penn to be paroled at Chew's house, "Solitude," at the Union Forge Ironworks in New Jersey. Six months later, after the British forces left the region, both men returned to Philadelphia on May 15, 1778.

After the Revolution, Benjamin Chew's broad social circles continued to include representative of many faiths, as well as friends and politicians representing many disparate points of view. Chew continued to participate in the meetings of the Tammany Society, to honor Tamanend, the Lenni-Lenape chief who first negotiated peace agreements with William Penn. Although Benjamin Chew was not a participant in the Constitutional Convention of 1787…he and his family were part of the city's new social circle that included the Washingtons, the John Adams, the William Binghams, and the Robert Morrises…In large measure this was because Chew's legal perspicacity offered expertise needed by the new government.

Trained in law at an early age by Andrew Hamilton, Benjamin Chew inherited his mentor's clients, the descendants of William Penn, including Thomas Penn (1702–1775) and his brother Richard Penn, Sr. (1706–1771), and their sons Governor John Penn (1729–1795), Richard Penn, Jr. (1734–1811), and John Penn (1760–1834). The Penn family was the basis of his private practice, and he represented them for six decades.

He had a lifelong personal friendship with George Washington, who is said to have treated Chew's children "as if they were his own." Chew lived and practiced law in Philadelphia four blocks from Independence Hall, and provided pro bono his knowledge of substantive law to America's Founding Fathers during the creation of the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights.

Benjamin Chew was the son of Samuel Chew, a physician and first Chief Justice of Delaware, and Mary Galloway Chew (1697–1734).

Chew took an interest in the field of law at an early age. In 1736, when he was 15 years old, he began to read law in the Philadelphia offices of the former Attorney General of Pennsylvania, Andrew Hamilton, then the speaker of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives. The year before, Hamilton had won a landmark case in American jurisprudence by his eloquent pro bono defense of the publisher Peter Zenger. It established the precedent of truth as an absolute defense against charges of libel.

Chew was strongly influenced by Hamilton's ideas about a free press, and also the reading materials which his mentor provided him, especially Sir Francis Bacon's Lawtracts. His understanding of English legal history, and especially the Charter of Liberties, enhanced by his later studies at London's Middle Temple, fostered Chew's enduring commitment to the civil liberties that are guaranteed by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, especially the right to free speech.

Following his father's death, Chew returned to Pennsylvania in 1744. He began to practice law in Dover, Delaware, while supporting his siblings and stepmother. Although Chew was raised in a Quaker family, he had first broken with Quaker tradition in 1741, when he agreed with his father, who had instructed a grand jury in Newcastle on the lawfulness of resistance to an armed force. In 1747, at age 25, Chew also went against Quaker tradition when he took the Oath of Attorney in Pennsylvania.

Chew moved to Philadelphia in 1754. He continued his legal responsibilities in both Delaware and Pennsylvania for the rest of his life. After early appointments in the Quaker-dominated government, following his second marriage he went into private practice in 1757; the following year joined the Anglican Church. He was taking a separate path to influence outside the Quaker elite. In 1758, Chew left the Quakers permanently and joined the Church of England.

Chew was highly effective in defending civil liberties and settling boundary disputes; he represented the descendants of William Penn and their proprietorship, the largest landholders in Pennsylvania, for more than 60 years. In 1757 Chew entered private practice: he derived most of his income from that, managing his second wife's considerable estate, and collecting quit-rents from his various properties. Chew continued the family practice of investing in land in the American colonies until the end of his life, expanding their holdings in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and New Jersey.

In 1771, Chew purchased the former house of his client, Governor John Penn, on South Third Street; Penn had returned to England to settle his father's (Richard Penn, Sr.) estate. The Chews entertained many visiting dignitaries, such as John Penn, Tench Francis, Jr., Robert, Thomas, and Samuel Wharton, Thomas Willing, John Cadwalader, Chief Justice William Allen and his wife Margaret, daughter of Andrew Hamilton, Dr. William Smith, Provost of the College of Philadelphia, botanist John Bartram, Edward Shippen, III, Edward Shippen, IV, and Peggy Shippen, Thomas Mifflin, later to become Governor of Pennsylvania, and Brigadier General Henry Bouquet, hero of the French and Indian War.

Abigail Adams referred to Chews' daughters as part of a "constellation of beauties" in Philadelphia. Margaret Chew (1760–1824) married Maryland Governor John E. Howard in 1787. Sophia (1769–1841) was invited to attend Martha Washington's first public event in Philadelphia. Harriet (1775–1861) was asked to entertain George Washington while his portrait was being painted. In 1800, she married the only son of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, signer of the Declaration of Independence, who built Homewood for them as a wedding gift. Throughout the Revolutionary War, George Washington aided the transfer of letters between Mr. and Mrs. Chew, during months when they were forced to live apart.

On August 4, 1777, the Executive Committee of the Continental Congress decided to place Chew in preventive detention in New Jersey. After Chew was released from parole in May 1778, he decided to move his family to Whitehall, their estate in Delaware, to buffer them from the political turbulence of Philadelphia. While in Delaware, the Chews rented their house on Third Street to Don Juan de Miralles (the Spanish representative to the American government); the Marquis de Chastellux (principal liaison officer between the French Commander-in-Chief and George Washington); and to George and Martha Washington, from November 1781 to March 1782, during the Second Continental Congress.

By 1783, the Chews concluded that the political situation was safe enough for their family to return to Philadelphia. They lived full-time in the house on South Third Street during the formation of the United States: the Constitutional Convention; the Congress of the Confederation; and in 1792, the official adoption of the Bill of Rights by the First United States Congress.

Benjamin Chew was Speaker of the Lower House for the Delaware counties (1753–1758); Attorney General and member of the Council of Pennsylvania (1754–1769); Recorder of Philadelphia City (1755–1774); Master of Rolls (1755–1774); and Provincial Councillor of Pennsylvania (1755).

In 1757 he began private practice, which was his chief pursuit for years, somewhat reducing his political appointments in the Quaker government. That year, he was also elected a trustee of The Academy and College of Philadelphia (the origins of the University of Pennsylvania) and continued as such until 1791. He also taught numerous law students. Foremost among Benjamin Chew's law students were Brigade Major Edward Tilghman and Judge William Tilghman. "These Tilghmans were so successful in the law that they were both offered the post of State Chief Justice in 1805."

He was selected as a Commissioner of Philadelphia (1761); appointed as Register-General of Wills (1765–1777); and as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania (1774–1777). During the American Revolutionary War, the Executive Council governing the new state removed him from office in 1777 and kept him in preventive detention in New Jersey until after the British forces left the Philadelphia region.

After the war, Chew resumed a position of influence in the new society and, eventually, its government. He was appointed as Judge and President of the High Court of Errors and Appeals (1791–1808).

After the state and national governments had been formed, in 1791, Chew was appointed by Thomas Mifflin, Pennsylvania's first Governor and the former President of the Continental Congress, to preside as the President over Pennsylvania's first High Court of Errors and Appeals. He held the position until he retired in 1808.

Prior to the American Revolution, Chew was friends with both George Washington and John Adams, and was a strong advocate for the colonies. As a lifelong pacifist, however, Chew believed that protest and reform were necessary to resolve the ongoing American conflicts with the British Parliament. Having been born and reared as a Quaker, he did not support active revolution. He maintained that position although he had left the Quakers and joined the Anglican Church in 1758. Early in the conflict, both the British and colonial sides claimed his allegiance since Chew had such a visible position in the colony and played so many important roles.

Chew was undecided about the correct course to take. "I have stated that an opposition of force of arms to the lawful authority of the king or his ministries…is high treason, but in the moment when the king or his ministries shall exceed the constitutional authority vested in them … submission to their mandates becomes treason." -Benjamin Chew, Chief Justice of Pennsylvania, in an address to the last provincial grand jury, April 10, 1776

On August 4, 1777, when General Howe and the British army were nearing Philadelphia, the Executive Council of the new government "issued a warrant for (Chew's) arrest on grounds of protecting the public safety. The Executive Council of the Continental Congress decided at the last minute against allowing Chew to remain at his home near Philadelphia. For his own safety, they decided to allow both Chew and the Governor John Penn to be paroled at Chew's house, "Solitude," at the Union Forge Ironworks in New Jersey. Six months later, after the British forces left the region, both men returned to Philadelphia on May 15, 1778.

After the Revolution, Benjamin Chew's broad social circles continued to include representative of many faiths, as well as friends and politicians representing many disparate points of view. Chew continued to participate in the meetings of the Tammany Society, to honor Tamanend, the Lenni-Lenape chief who first negotiated peace agreements with William Penn. Although Benjamin Chew was not a participant in the Constitutional Convention of 1787…he and his family were part of the city's new social circle that included the Washingtons, the John Adams, the William Binghams, and the Robert Morrises…In large measure this was because Chew's legal perspicacity offered expertise needed by the new government.

Bio by: Dennis Hubscher

Family Members

-

![]()

Mary Chew Wilcocks

1747–1794

-

Elizabeth Chew Tilghman

1751–1842

-

![]()

Sarah "Sally" Chew Galloway

1753–1796

-

![]()

Benjamin Chew Jr

1758–1844

-

![]()

Margretta Oswald "Peggy" Chew Howard

1760–1827

-

![]()

Henrietta Chew

1767–1848

-

![]()

Sophia Chew Philips

1769–1836

-

![]()

Maria Chew

1771–1840

-

![]()

Harriett Chew Carroll

1775–1861

-

![]()

Catherine Chew

1779–1831

Advertisement

Advertisement