Elizabeth Embich Shindel Hutter was the daughter of Jacob and Elizabeth (Leisenring)Shindel. She was married to Edwin Wilson Hutter,a long-time Lutheran Minister. They were the parents of Christian Jacob and James Buchanan Hutter.

* Info supplied by Nancy Lowe.

ELIZABETH E. HUTTER, HOMEFRONT HERO

During the Civil War Elizabeth E. Hutter was a volunteer nurse, Union Volunteer Refreshment Saloon worker, fundraiser for the United States Sanitary Commission and other causes, advocate for children orphaned by the War, and personal friend of Abraham Lincoln. A woman of remarkable intelligence and energy, a natural leader who was also highly personable, she was unswerving in her commitment to community and country. Elizabeth Hutter well deserves to be lauded as a Philadelphia homefront hero.

Elizabeth Eimbich Shindel was born on November 18, 1821 in Lebanon, PA to a proud Pennsylvania Deutch family that espoused education, industry, and good works, including both acts of charity and commitment to civic causes. The Shindels were also patriots: her great-grandfather and grandfather had served in the Revolutionary War, her father in the War of 1812, and her brother and various cousins would serve in the Union Army during the Civil War.

Although her father died six days before her ninth birthday, the extended Shindel family, which included several Lutheran ministers, ensured that she and her siblings received good educations and personal mentoring. In her early teens Elizabeth was sent to the prestigious Moravian Seminary for Girls in Bethlehem, PA, an institution that offered a rigorous academic curriculum.

It was during her sojourn in Bethlehem that Elizabeth made the acquaintance of Edwin Wilson Hutter. Although only in his mid-20s, Edwin Hutter was already the editor/publisher of several newspapers, as well as postmaster of Allentown, PA. The couple was married at the Zion Lutheran Church in Lebanon on March 25, 1838. Elizabeth was only 17 years old, but the marriage proved to be a lasting, happy alliance of like minds and spirits.

Edwin's career continued on an upward trajectory. He was awarded a succession of political appointments in Harrisburg, the state capital. He also acquired additional newspapers, including the Lancaster Intelligencer and Journal. While living in Lancaster, the Hutters became close friends with James Buchanan, then a U.S. Senator, and his niece Harriet Lane. Thus when James Buchanan was appointed Secretary of State in 1845 during the Polk administration, Edwin Hutter was invited to serve as Buchanan's personal secretary.

And so the Hutters moved to the nation's capital, where Elizabeth soon established herself as a star of Washington society. The Hutters counted among their guests and friends such eminent persons as Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, John Calhoun, Chief Justice Roger Taney, General Winfield Scott, Zachary Taylor, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and more. They also made the acquaintance of Abraham Lincoln when he arrived in Washington in 1847 to serve a term in Congress.

Edwin became Assistant Secretary of State during the War with Mexico, and it looked like the Hutters would be staying in Washington. However, the Hutters were then struck by personal tragedy when they lost both of their young sons, Christian Jacob and James Buchanan Hutter, to scarlet fever. Completely stricken, Elizabeth and Edwin turned to their faith for comfort. Even though President Polk tried to keep Edwin in public life by offering him the position of U.S. Minister to Rome, he decided to leave politics to become a pastor.

In 1849 he went to Baltimore for his seminary studies and then was ordained by the Lutheran Synod of Pennsylvania in June of 1850. In August, after he had given guest sermons at several Philadelphia churches, Edwin was invited to serve as pastor of St. Matthew's Evangelical Lutheran Church. The Hutters moved to Philadelphia in September, 1850, and embraced the City of Brotherly Love as their permanent home.

Both Hutters dedicated themselves to benevolent works. By 1851 Elizabeth was on the Board of Managers of the Philadelphia Rosine Association, a group dedicated to helping women of the streets. Two years later she spearheaded the founding of the Northern Home for Friendless Children, a residential facility that could care for or facilitate placements for destitute children whose parents or guardians had died or were otherwise unable to provide for them.

Through vigorous fundraising efforts, which included a series of benefit concerts, floral fairs and more, Elizabeth and other concerned citizens were able to raise sufficient monies to build a large facility at 23rd and Brown Streets in Philadelphia, where up to 100 children at a time could be comfortably housed. In addition to food, shelter and clothing, Northern Home children also received schooling and training in practical trades. Elizabeth Hutter became President of its Board of Managers, a position that she held until shortly before her death 42 years later.

When the War of the Rebellion broke out in April, 1861, the Hutters were galvanized to support the Union cause and render aid to its defenders. Both spent many hours at the Union Volunteer Refreshment Saloon, located not far from the train depot at Broad and Prime (now Washington) Streets in the Southwark section of the city. There they helped provide hot meals and other accommodations to the troops passing to or from the front. Like its neighbor, the Cooper Shop Refreshment Saloon, the Union Volunteer Refreshment Saloon soon expanded to include a small hospital, where Elizabeth helped tend to sick and wounded soldiers while Edwin offered spiritual solace.

The Hutters also began making forays to the Washington, DC area and to Northern Virginia to deliver much-needed supplies of food, clothing, and sometimes money to Federal recruits. In July 1861, responding to an urgent telegram from their friend, the former congressman, now President Lincoln, the Hutters were issued a special Presidential pass and were thus the first civilians to go the front to help the wounded after the First Battle of Bull Run.

As the War progressed and the numbers of casualties continued to mount, more and more military hospitals were established to take care of the sick and wounded. Elizabeth served as a volunteer nurses at various local hospitals, and Edwin joined her in providing what comfort they could for those suffering bodies and souls. On July 4, 1863, traveling again under a special Presidential pass, Elizabeth Hutter arrived by special car at Gettysburg, where she and other volunteers stayed there for many days to help care for the wounded, both Union and Confederate.

In 1864 Elizabeth Hutter co-chaired the Committee of Labor, Income and Revenue for the Great Central Fair, which was held that June at Logan Square, Philadelphia, to raise money for the U.S. Sanitary Commission. The Fair was a regional effort, endorsed by the governors of New Jersey and Delaware as well as Pennsylvania; it was a cause enthusiastically embraced by all loyal and charitable citizens, and about a hundred special committees were formed to work diligently to ensure the its success. Each committee was in charge of a distinct channel of contribution, all centering in the end in the common reservoir of fundraising for the Sanitary Commission. Elizabeth Hutter's committee raised almost a quarter of million dollars, still a lot of money today, but a phenomenal amount in 1864.

The Northern Home for Friendless Children had opened its doors to needy children whose fathers had volunteered to serve the Union, whether or not those brave men survived the ordeals of War. It was understood that if a child's father died in service, the Northern Home would provide permanent care for that orphan. As the War continued, Elizabeth Hutter could see that the battlefield carnage was resulting in ever-growing numbers of these orphans. Thus she proposed the creation of institutions to provide shelter and education specifically for these children who had been left bereft by the War. She spearheaded the fundraising campaign to build the Philadelphia Soldiers' and Sailors' Orphans Institute, which officially opened in March 1865 adjacent to the Northern Home for Friendless Children.

It became a model for many such institutions. Elizabeth Hutter met with President Lincoln at the White House on several occasions during the War, including an appointment in early November 1864 and again in February 1865, when she discussed with him the establishment of a network of similar asylums in each state to help care for war orphans.

The North celebrated joyously the news of General Lee's surrender on April 9, 1865. Then, less than a week later, came the shocking news that President Lincoln had been assassinated. As a patriotic citizen, Elizabeth Hutter mourned the death of this great leader; as a person, she grieved the loss of a dear friend. On April 22nd she and two other Philadelphia ladies were accorded the sorrowful honor of laying a cross of white flowers on Lincoln's casket as he lay in state at Independence Hall, in the very room where the Declaration of Independence had been signed.

The Civil War had finally ended, but it had left in its wake thousands of needy children. In 1866, former Union General, now Pennsylvania Governor John W. Geary appointed Elizabeth Hutter to be "Lady Inspector of the Department of Soldiers' Orphans." She was the first woman in the history of the Commonwealth to be granted a Governor's commission, and she served in this role up until the early 1880s.

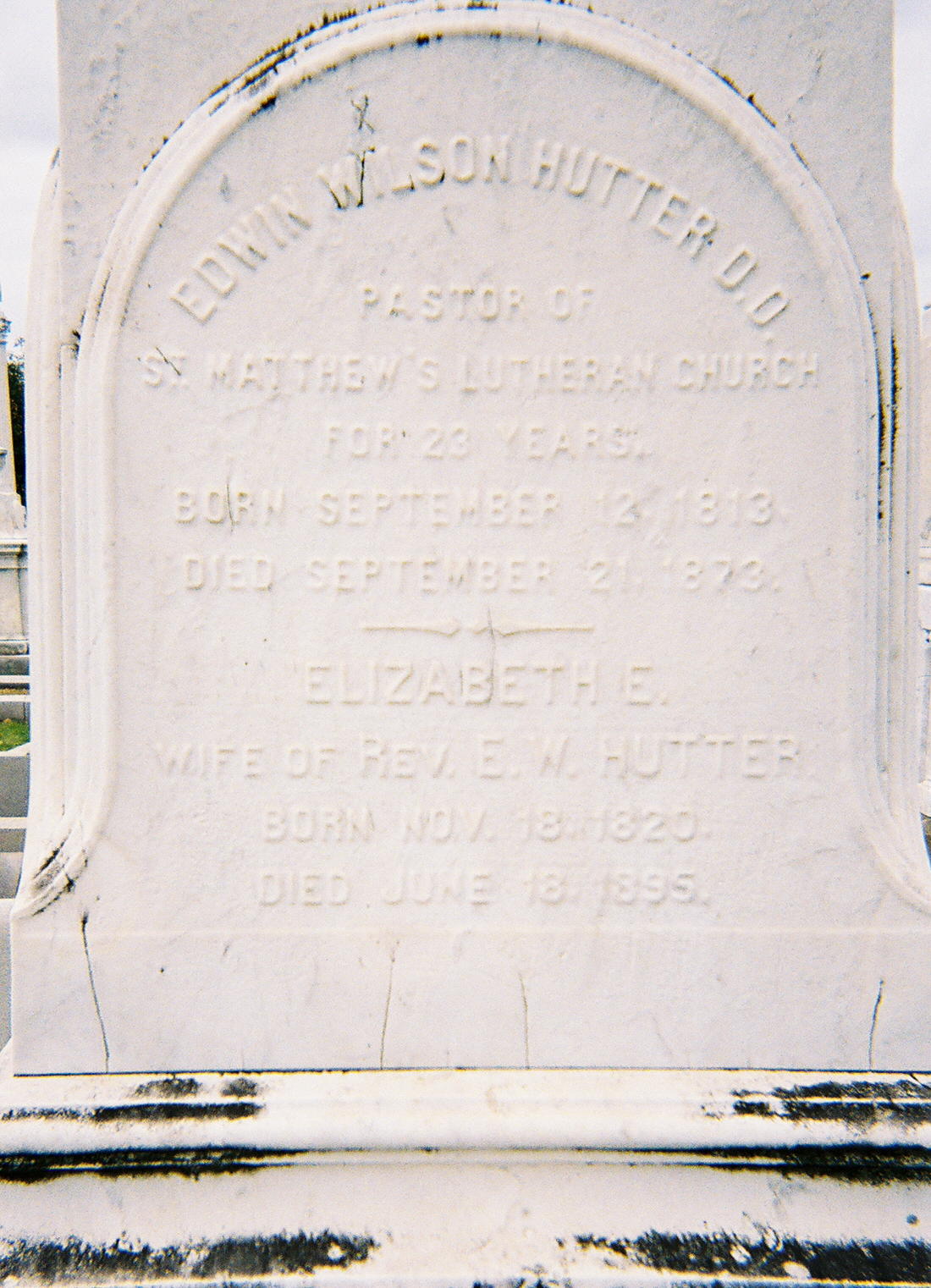

In 1871 Edwin Hutter's health began to fail, but he continued to labor unremittingly on behalf of his church and parishioners, as well as orphaned children and so many others. His condition worsened, and he passed away on September 21, 1873, less than two weeks after his 60th birthday.

Although Elizabeth never ceased to grieve for her beloved husband, she rallied and continued to be very active in philanthropic works and civic causes for her remaining 22 years. In addition to serving as state inspector of schools for war orphans and as President of the Board of Managers for the Northern Home for Friendless Children, Elizabeth Hutter was active in raising contributions of supplies and funds to aid refugees in times of crisis, such as after the Great Chicago Fire of October 1871 and the Johnstown Flood of May 1889. In 1876 she headed the Executive Committee of the State Educational Department for the Centennial Exposition held here in Philadelphia and was presented with a gold medal as a token of appreciation for her services.

On June 18, 1895, after a brief illness she died in her home on Race Street. Four days later she was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery, where she was laid next to her husband. Their two children and several other family members are buried nearby.

But Elizabeth Hutter's legacy continues. Renamed the Northern Home for Children, the organization she had founded in 1853 remained at 23rd and Brown Streets until 1923, when it moved to its current six-acre site in the Roxborough section of Philadelphia. Now known as Northern Children's Services, this social agency still continues to provide assistance to children at risk; it offers a broad range of preventative and interventional services each year to some 3000 children and their families in the Delaware Valley.

Elizabeth E. Hutter is still a homefront hero.

Elizabeth Embich Shindel Hutter was the daughter of Jacob and Elizabeth (Leisenring)Shindel. She was married to Edwin Wilson Hutter,a long-time Lutheran Minister. They were the parents of Christian Jacob and James Buchanan Hutter.

* Info supplied by Nancy Lowe.

ELIZABETH E. HUTTER, HOMEFRONT HERO

During the Civil War Elizabeth E. Hutter was a volunteer nurse, Union Volunteer Refreshment Saloon worker, fundraiser for the United States Sanitary Commission and other causes, advocate for children orphaned by the War, and personal friend of Abraham Lincoln. A woman of remarkable intelligence and energy, a natural leader who was also highly personable, she was unswerving in her commitment to community and country. Elizabeth Hutter well deserves to be lauded as a Philadelphia homefront hero.

Elizabeth Eimbich Shindel was born on November 18, 1821 in Lebanon, PA to a proud Pennsylvania Deutch family that espoused education, industry, and good works, including both acts of charity and commitment to civic causes. The Shindels were also patriots: her great-grandfather and grandfather had served in the Revolutionary War, her father in the War of 1812, and her brother and various cousins would serve in the Union Army during the Civil War.

Although her father died six days before her ninth birthday, the extended Shindel family, which included several Lutheran ministers, ensured that she and her siblings received good educations and personal mentoring. In her early teens Elizabeth was sent to the prestigious Moravian Seminary for Girls in Bethlehem, PA, an institution that offered a rigorous academic curriculum.

It was during her sojourn in Bethlehem that Elizabeth made the acquaintance of Edwin Wilson Hutter. Although only in his mid-20s, Edwin Hutter was already the editor/publisher of several newspapers, as well as postmaster of Allentown, PA. The couple was married at the Zion Lutheran Church in Lebanon on March 25, 1838. Elizabeth was only 17 years old, but the marriage proved to be a lasting, happy alliance of like minds and spirits.

Edwin's career continued on an upward trajectory. He was awarded a succession of political appointments in Harrisburg, the state capital. He also acquired additional newspapers, including the Lancaster Intelligencer and Journal. While living in Lancaster, the Hutters became close friends with James Buchanan, then a U.S. Senator, and his niece Harriet Lane. Thus when James Buchanan was appointed Secretary of State in 1845 during the Polk administration, Edwin Hutter was invited to serve as Buchanan's personal secretary.

And so the Hutters moved to the nation's capital, where Elizabeth soon established herself as a star of Washington society. The Hutters counted among their guests and friends such eminent persons as Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, John Calhoun, Chief Justice Roger Taney, General Winfield Scott, Zachary Taylor, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and more. They also made the acquaintance of Abraham Lincoln when he arrived in Washington in 1847 to serve a term in Congress.

Edwin became Assistant Secretary of State during the War with Mexico, and it looked like the Hutters would be staying in Washington. However, the Hutters were then struck by personal tragedy when they lost both of their young sons, Christian Jacob and James Buchanan Hutter, to scarlet fever. Completely stricken, Elizabeth and Edwin turned to their faith for comfort. Even though President Polk tried to keep Edwin in public life by offering him the position of U.S. Minister to Rome, he decided to leave politics to become a pastor.

In 1849 he went to Baltimore for his seminary studies and then was ordained by the Lutheran Synod of Pennsylvania in June of 1850. In August, after he had given guest sermons at several Philadelphia churches, Edwin was invited to serve as pastor of St. Matthew's Evangelical Lutheran Church. The Hutters moved to Philadelphia in September, 1850, and embraced the City of Brotherly Love as their permanent home.

Both Hutters dedicated themselves to benevolent works. By 1851 Elizabeth was on the Board of Managers of the Philadelphia Rosine Association, a group dedicated to helping women of the streets. Two years later she spearheaded the founding of the Northern Home for Friendless Children, a residential facility that could care for or facilitate placements for destitute children whose parents or guardians had died or were otherwise unable to provide for them.

Through vigorous fundraising efforts, which included a series of benefit concerts, floral fairs and more, Elizabeth and other concerned citizens were able to raise sufficient monies to build a large facility at 23rd and Brown Streets in Philadelphia, where up to 100 children at a time could be comfortably housed. In addition to food, shelter and clothing, Northern Home children also received schooling and training in practical trades. Elizabeth Hutter became President of its Board of Managers, a position that she held until shortly before her death 42 years later.

When the War of the Rebellion broke out in April, 1861, the Hutters were galvanized to support the Union cause and render aid to its defenders. Both spent many hours at the Union Volunteer Refreshment Saloon, located not far from the train depot at Broad and Prime (now Washington) Streets in the Southwark section of the city. There they helped provide hot meals and other accommodations to the troops passing to or from the front. Like its neighbor, the Cooper Shop Refreshment Saloon, the Union Volunteer Refreshment Saloon soon expanded to include a small hospital, where Elizabeth helped tend to sick and wounded soldiers while Edwin offered spiritual solace.

The Hutters also began making forays to the Washington, DC area and to Northern Virginia to deliver much-needed supplies of food, clothing, and sometimes money to Federal recruits. In July 1861, responding to an urgent telegram from their friend, the former congressman, now President Lincoln, the Hutters were issued a special Presidential pass and were thus the first civilians to go the front to help the wounded after the First Battle of Bull Run.

As the War progressed and the numbers of casualties continued to mount, more and more military hospitals were established to take care of the sick and wounded. Elizabeth served as a volunteer nurses at various local hospitals, and Edwin joined her in providing what comfort they could for those suffering bodies and souls. On July 4, 1863, traveling again under a special Presidential pass, Elizabeth Hutter arrived by special car at Gettysburg, where she and other volunteers stayed there for many days to help care for the wounded, both Union and Confederate.

In 1864 Elizabeth Hutter co-chaired the Committee of Labor, Income and Revenue for the Great Central Fair, which was held that June at Logan Square, Philadelphia, to raise money for the U.S. Sanitary Commission. The Fair was a regional effort, endorsed by the governors of New Jersey and Delaware as well as Pennsylvania; it was a cause enthusiastically embraced by all loyal and charitable citizens, and about a hundred special committees were formed to work diligently to ensure the its success. Each committee was in charge of a distinct channel of contribution, all centering in the end in the common reservoir of fundraising for the Sanitary Commission. Elizabeth Hutter's committee raised almost a quarter of million dollars, still a lot of money today, but a phenomenal amount in 1864.

The Northern Home for Friendless Children had opened its doors to needy children whose fathers had volunteered to serve the Union, whether or not those brave men survived the ordeals of War. It was understood that if a child's father died in service, the Northern Home would provide permanent care for that orphan. As the War continued, Elizabeth Hutter could see that the battlefield carnage was resulting in ever-growing numbers of these orphans. Thus she proposed the creation of institutions to provide shelter and education specifically for these children who had been left bereft by the War. She spearheaded the fundraising campaign to build the Philadelphia Soldiers' and Sailors' Orphans Institute, which officially opened in March 1865 adjacent to the Northern Home for Friendless Children.

It became a model for many such institutions. Elizabeth Hutter met with President Lincoln at the White House on several occasions during the War, including an appointment in early November 1864 and again in February 1865, when she discussed with him the establishment of a network of similar asylums in each state to help care for war orphans.

The North celebrated joyously the news of General Lee's surrender on April 9, 1865. Then, less than a week later, came the shocking news that President Lincoln had been assassinated. As a patriotic citizen, Elizabeth Hutter mourned the death of this great leader; as a person, she grieved the loss of a dear friend. On April 22nd she and two other Philadelphia ladies were accorded the sorrowful honor of laying a cross of white flowers on Lincoln's casket as he lay in state at Independence Hall, in the very room where the Declaration of Independence had been signed.

The Civil War had finally ended, but it had left in its wake thousands of needy children. In 1866, former Union General, now Pennsylvania Governor John W. Geary appointed Elizabeth Hutter to be "Lady Inspector of the Department of Soldiers' Orphans." She was the first woman in the history of the Commonwealth to be granted a Governor's commission, and she served in this role up until the early 1880s.

In 1871 Edwin Hutter's health began to fail, but he continued to labor unremittingly on behalf of his church and parishioners, as well as orphaned children and so many others. His condition worsened, and he passed away on September 21, 1873, less than two weeks after his 60th birthday.

Although Elizabeth never ceased to grieve for her beloved husband, she rallied and continued to be very active in philanthropic works and civic causes for her remaining 22 years. In addition to serving as state inspector of schools for war orphans and as President of the Board of Managers for the Northern Home for Friendless Children, Elizabeth Hutter was active in raising contributions of supplies and funds to aid refugees in times of crisis, such as after the Great Chicago Fire of October 1871 and the Johnstown Flood of May 1889. In 1876 she headed the Executive Committee of the State Educational Department for the Centennial Exposition held here in Philadelphia and was presented with a gold medal as a token of appreciation for her services.

On June 18, 1895, after a brief illness she died in her home on Race Street. Four days later she was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery, where she was laid next to her husband. Their two children and several other family members are buried nearby.

But Elizabeth Hutter's legacy continues. Renamed the Northern Home for Children, the organization she had founded in 1853 remained at 23rd and Brown Streets until 1923, when it moved to its current six-acre site in the Roxborough section of Philadelphia. Now known as Northern Children's Services, this social agency still continues to provide assistance to children at risk; it offers a broad range of preventative and interventional services each year to some 3000 children and their families in the Delaware Valley.

Elizabeth E. Hutter is still a homefront hero.