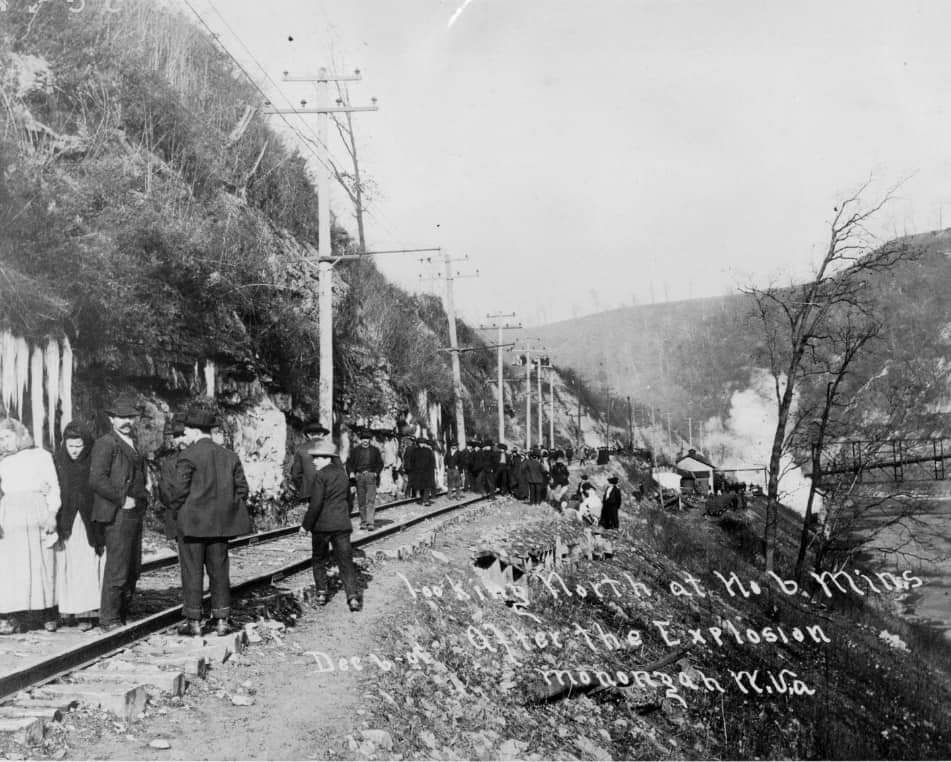

Rescuers going into the mouth of the No. 6 mine, newspaper photo.

On Friday, December 6, 1907, there were officially 367 men in the two mines, although the actual number was much higher as officially registered workers often took their children and other relatives into the mine to help. At 10:28 AM an explosion occurred that killed most of the men inside the mine instantly. The blast caused considerable damage to both the mine and the surface. The ventilation systems, necessary to keep fresh air supplied to the mine, were destroyed along with many railcars and other equipment. Inside the mine the timbers supporting the roof were blown down which caused further problems as the roof collapsed. An official cause of the explosion was not determined, but investigators at the time believed that an electrical spark or one of the miners' open flame lamps ignited coal dust or methane gas.[1]

Rescue attempts

Artistic view of the explosion at the No. 8 mine.

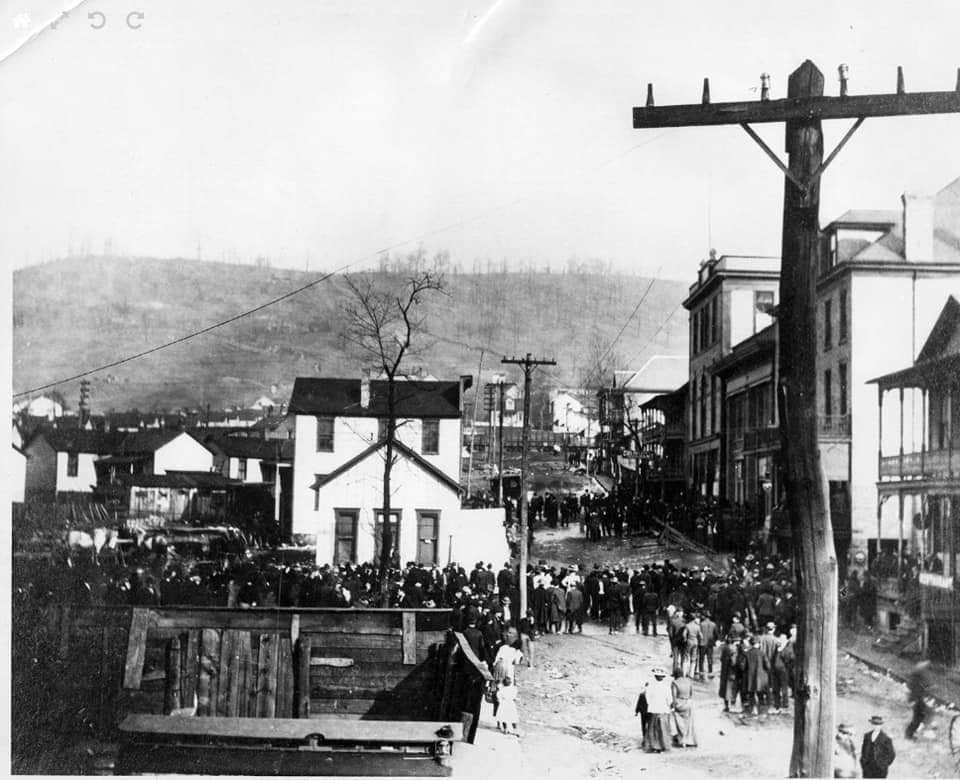

During the early days of coal mining, time was of the essence to bring people out alive. The first volunteer rescuers entered the two mines twenty-five minutes after the initial explosion.[2] The biggest threats to rescuers were the fumes, particularly "blackdamp", a mix of carbon dioxide and nitrogen that contains no oxygen, and "whitedamp", which is carbon monoxide. The lack of breathing apparatus at the time made venturing into these areas impossible. Rescuers could only stay in the mine for 15 minutes at a time.[3] In a vain effort to protect themselves, some of the miners tried to cover their faces with jackets or other pieces of cloth. While this might have been able to filter out particulate matter, it would not have been able to protect the miners in an oxygen-free environment.[4] The toxic fume problems were compounded by the infrastructural damage caused by the initial explosion: mines require large ventilation fans to prevent toxic gas buildup, and the explosion at Monongah had destroyed all of the ventilation equipment. The inability to clear the mine of gases transformed the rescue effort into a recovery effort. One Polish miner was rescued, and four Italian miners escaped.[5] The official death toll stood at 362, 171 of them Italian migrants.[5]

As a result of the explosion, along with other disasters, the public began demanding additional oversight to help regulate the mines. In 1910 Congress created the United States Bureau of Mines, with the goal of investigating and inspecting mines to reduce explosions and to limit the waste of human and natural resources. In addition, the Bureau of Mines set up field officers that would train mine crews, provide rescue services, and investigate disasters when they do occur.[6]

Memorials

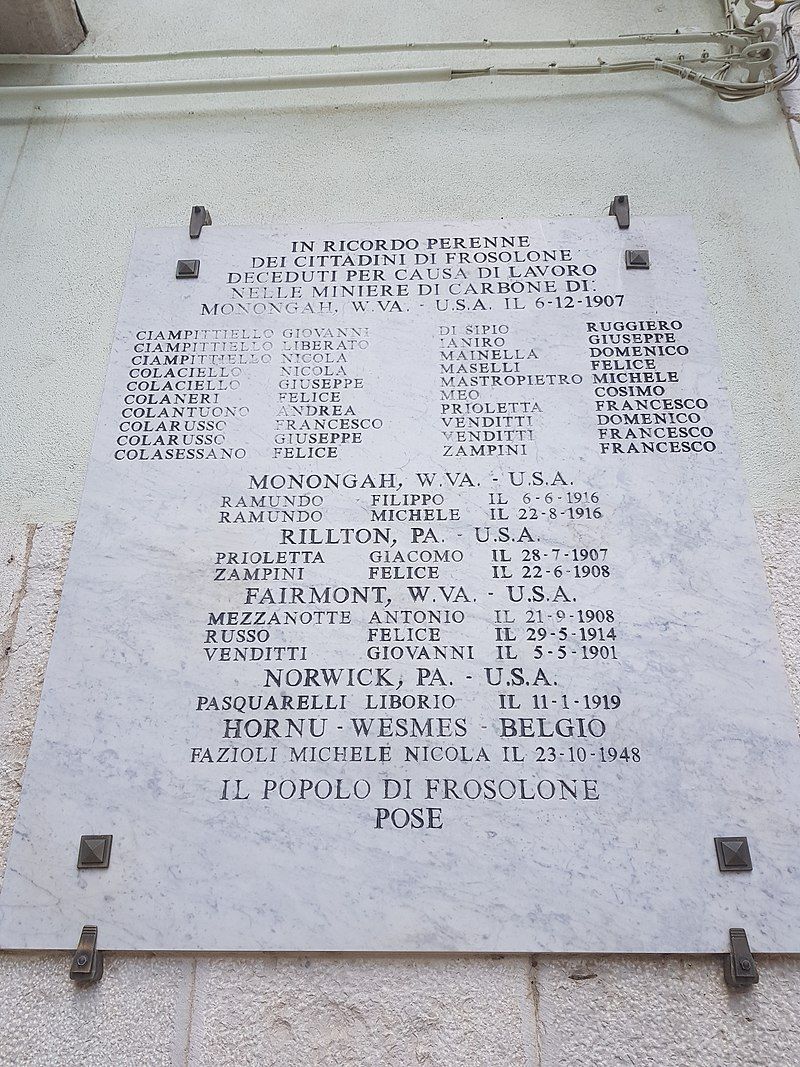

In 2003, to commemorate the explosion, the Italian commune of San Giovanni in Fiore, from which many of the miners had emigrated, erected a memorial with the inscription Per non dimenticare minatori calabresi morti nel West Virginia (USA). Il sacrificio di quegli uomini forti tempri le nuove generazioni. Monongah, 6 dicembre 1907; San Giovanni in Fiore, 6 dicembre 2003 ("Lest we forget the Calabrian miners dead in West Virginia (USA). The sacrifice of those strong men shall bolster new generations. Monongah, December 6, 1907, San Giovanni in Fiore, December 6, 2003")[7]

In 2007, there was a statue that was dedicated to the widowers from the mine explosion. The statue can be referred to as the Monongah Heroine.[8] The Monongah Heroine shows a woman named Caterina Davia. She is pictured in the statue due to her love for her husband who was lost in the explosion. She would show her love by loading up coal for 29 years and dumping it in her backyard as a tribute to him. This statue was meant to show that traditions should never be forgotten and that was the goal of Father Joseph Briggs who had it put there.[9]

In 2007, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the explosion, the Italian region of Molise presented a bell to the town of Monongah. Today the bell sits in the Monongah town square.[10]

In 2009, the President of the Italian Republic, Giorgio Napolitano, conferred the honor of "Stella al Merito del Lavoro" (Star of Reward of Work) upon the victims of the disaster.[11]

Relief Fund

After the deadly explosion there was a race to find ways to help those affected by it. There were many committees that were put together solely for the Monongah Mine Disaster. The main committee in charge of this disaster was the Monongah Mine Relief Committee after two other committees agreed on a merger. Once the Monongah Mine Relief Committee was created there were two committees within the it to split up further jobs. The two subcommittees were the Subscription Committee and Executive Committee. The Executive Committee was in charge of raising awareness around the nation about what had happened in the Monongah Mine Disaster. While the Subscription Committee was in charge of finding ways to receive aid.[12]

There were also other people who helped with the relief fund and they created relief funds of their own to help the cause. One of these people would be Andrew Carnegie and his Hero Relief Fund. This Hero Relief Fund was for those who were killed trying to save those trapped in the mine but were not employed by the mining company. After the assembly of the Monongah Mine Relief Committee Carnegie's foundation had donated $35,000 to them to help with relief funds. The Red Cross helped out as well thanks to a woman named Margaret F. Byington. She would help with the survey they had made for the survivors. This survey would be given to family to assess what they needed help with. With the involvement of Byington the Red Cross would make drastic changes to their policies as this was the first manmade disaster they had assisted on.[13]

Preventions

Even after the end of investigations the true cause of the disaster may never be known, but problems from those investigations arose. After realizing these problems it became aware to people that there could be more safety protocols in place to better benefit the miners. One of these problems, would be that the two mines were connected which would allow for more casualties. It was known to be catastrophic as many states had banned it from being put into place. Even after this problem came to a mining panel the companies did nothing to phase out the connection between the two mines. The next problem would be the introduction of using mechanical equipment as this would increase the amount of dust in the mines. The dust would increase the probability of there being a fire. The last prevention was the lack of watering and dust removal systems being up to standard. A contributing factor to this was immigrant workers were not aware of this.

Rescuers going into the mouth of the No. 6 mine, newspaper photo.

On Friday, December 6, 1907, there were officially 367 men in the two mines, although the actual number was much higher as officially registered workers often took their children and other relatives into the mine to help. At 10:28 AM an explosion occurred that killed most of the men inside the mine instantly. The blast caused considerable damage to both the mine and the surface. The ventilation systems, necessary to keep fresh air supplied to the mine, were destroyed along with many railcars and other equipment. Inside the mine the timbers supporting the roof were blown down which caused further problems as the roof collapsed. An official cause of the explosion was not determined, but investigators at the time believed that an electrical spark or one of the miners' open flame lamps ignited coal dust or methane gas.[1]

Rescue attempts

Artistic view of the explosion at the No. 8 mine.

During the early days of coal mining, time was of the essence to bring people out alive. The first volunteer rescuers entered the two mines twenty-five minutes after the initial explosion.[2] The biggest threats to rescuers were the fumes, particularly "blackdamp", a mix of carbon dioxide and nitrogen that contains no oxygen, and "whitedamp", which is carbon monoxide. The lack of breathing apparatus at the time made venturing into these areas impossible. Rescuers could only stay in the mine for 15 minutes at a time.[3] In a vain effort to protect themselves, some of the miners tried to cover their faces with jackets or other pieces of cloth. While this might have been able to filter out particulate matter, it would not have been able to protect the miners in an oxygen-free environment.[4] The toxic fume problems were compounded by the infrastructural damage caused by the initial explosion: mines require large ventilation fans to prevent toxic gas buildup, and the explosion at Monongah had destroyed all of the ventilation equipment. The inability to clear the mine of gases transformed the rescue effort into a recovery effort. One Polish miner was rescued, and four Italian miners escaped.[5] The official death toll stood at 362, 171 of them Italian migrants.[5]

As a result of the explosion, along with other disasters, the public began demanding additional oversight to help regulate the mines. In 1910 Congress created the United States Bureau of Mines, with the goal of investigating and inspecting mines to reduce explosions and to limit the waste of human and natural resources. In addition, the Bureau of Mines set up field officers that would train mine crews, provide rescue services, and investigate disasters when they do occur.[6]

Memorials

In 2003, to commemorate the explosion, the Italian commune of San Giovanni in Fiore, from which many of the miners had emigrated, erected a memorial with the inscription Per non dimenticare minatori calabresi morti nel West Virginia (USA). Il sacrificio di quegli uomini forti tempri le nuove generazioni. Monongah, 6 dicembre 1907; San Giovanni in Fiore, 6 dicembre 2003 ("Lest we forget the Calabrian miners dead in West Virginia (USA). The sacrifice of those strong men shall bolster new generations. Monongah, December 6, 1907, San Giovanni in Fiore, December 6, 2003")[7]

In 2007, there was a statue that was dedicated to the widowers from the mine explosion. The statue can be referred to as the Monongah Heroine.[8] The Monongah Heroine shows a woman named Caterina Davia. She is pictured in the statue due to her love for her husband who was lost in the explosion. She would show her love by loading up coal for 29 years and dumping it in her backyard as a tribute to him. This statue was meant to show that traditions should never be forgotten and that was the goal of Father Joseph Briggs who had it put there.[9]

In 2007, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the explosion, the Italian region of Molise presented a bell to the town of Monongah. Today the bell sits in the Monongah town square.[10]

In 2009, the President of the Italian Republic, Giorgio Napolitano, conferred the honor of "Stella al Merito del Lavoro" (Star of Reward of Work) upon the victims of the disaster.[11]

Relief Fund

After the deadly explosion there was a race to find ways to help those affected by it. There were many committees that were put together solely for the Monongah Mine Disaster. The main committee in charge of this disaster was the Monongah Mine Relief Committee after two other committees agreed on a merger. Once the Monongah Mine Relief Committee was created there were two committees within the it to split up further jobs. The two subcommittees were the Subscription Committee and Executive Committee. The Executive Committee was in charge of raising awareness around the nation about what had happened in the Monongah Mine Disaster. While the Subscription Committee was in charge of finding ways to receive aid.[12]

There were also other people who helped with the relief fund and they created relief funds of their own to help the cause. One of these people would be Andrew Carnegie and his Hero Relief Fund. This Hero Relief Fund was for those who were killed trying to save those trapped in the mine but were not employed by the mining company. After the assembly of the Monongah Mine Relief Committee Carnegie's foundation had donated $35,000 to them to help with relief funds. The Red Cross helped out as well thanks to a woman named Margaret F. Byington. She would help with the survey they had made for the survivors. This survey would be given to family to assess what they needed help with. With the involvement of Byington the Red Cross would make drastic changes to their policies as this was the first manmade disaster they had assisted on.[13]

Preventions

Even after the end of investigations the true cause of the disaster may never be known, but problems from those investigations arose. After realizing these problems it became aware to people that there could be more safety protocols in place to better benefit the miners. One of these problems, would be that the two mines were connected which would allow for more casualties. It was known to be catastrophic as many states had banned it from being put into place. Even after this problem came to a mining panel the companies did nothing to phase out the connection between the two mines. The next problem would be the introduction of using mechanical equipment as this would increase the amount of dust in the mines. The dust would increase the probability of there being a fire. The last prevention was the lack of watering and dust removal systems being up to standard. A contributing factor to this was immigrant workers were not aware of this.

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement