Mr. Burns, who was 83 years old, died of complications following triple-bypass heart surgery in April.

''Arthur Burns was a staunch supporter of the Federal Reserve as an institution and a firm friend of many of us within it,'' said Paul A. Volcker, current chairman of the Federal Reserve, in a statement. He ''brought to his position force of personality, intellectual vigor and physical endurance.'' Served Under Eisenhower

Highly respected within the economics profession for his scholarship, Mr. Burns received greater public notice for his service in Washington, which began in 1953 when he became chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

His position of greatest influence was as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, from 1970 to 1978, one of the nation's most tumultuous and difficult economic periods.

From that post, as well as from all others, the Austrian-born Mr. Burns brought to bear an intellectual conservatism and a firm conviction of the dangers of inflation that was tempered by a commitment to a New Deal role for government in promoting economic prosperity.

''The only responsible course open to us,'' he once said, ''is to fight inflation tenaciously.'' But he promptly added: ''There is no way to turn back the clock and restore the environment of a bygone era. We can no longer cope with inflation by letting recessions run their course'' or by cutting programs that help the sick, the aged or the poor.

Although he served almost exclusively under Republican Presidents, Mr. Burns frequently made his mark by asserting a philosophical independence. On several issues, he clung to unpopular views that later became widely accepted, often by Democrats. PU FIRST AND LAST ADD BURNS OBIT pu first and last Burns Obit xxx by Democrats In 1969 and 1970, he advocated restraints on wage increases. In 1974 and 1975, when a deepening recession led to political moves to end the Federal Reserve Board's independence, Mr. Burns insisted that monetary restraint be maintained. And when Ronald Reagan suggested in 1980 and 1981 that people's ''expectations'' were important in determining economic performance, Mr. Burns reiterated his conviction that concrete action to reduce the budget deficit was more important than tax reductions aimed at expectations.

To all of his jobs, he brought a legendary capacity for hard work, an unfailingly courteous manner, a rarely questioned sense of integrity and a mind acknowledged even by his critics to be extraordinary.

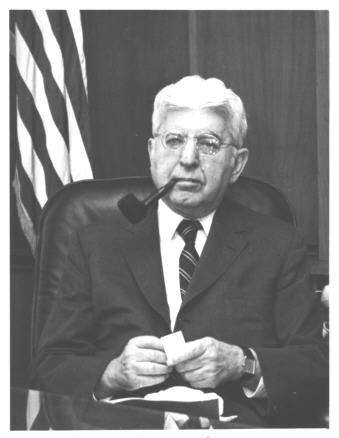

Throughout, he was an unmistakable presence to millions of Americans, with his bushy gray hair parted down the middle, wire-rimmed spectacles, jutting pipe and precise, slightly nasal voice that maintained its soft-spoken tone under the most scathing questioning. Held Many Advisory Posts

Mr. Burns also served as President Richard M. Nixon's adviser on economic and other matters in 1969, as the Ambassador to West Germany from 1981 to 1985 and in an array of advisory posts. Since returning from Bonn, he had resumed his place as distinguished scholar in residence at the American Enterprise Institute.

As Ambassador, he quickly gained wide respect. West Germany's Chancellor, Helmut Schmidt, thanked President Reagan for sending him Mr. Burns, calling him ''one of the most knowledgeable financial and monetary experts in the world.'' The two were very close and Mr. Burns was considered a highly successful Ambassador.

Mr. Burns presided over the Federal Reserve at a time when the nation's inflation accelerated. In retrospect, the performance of the Federal Reserve in controlling the money supply during Mr. Burns's tenure received mixed grades. And if the public eventually awoke to the dangers of inflation, Mr. Burns's role in that educational process sometimes seemed indistinct.

''I devoted a good part of my life to trying to awaken the country to the dangers of inflation,'' he once said in a reflective moment. ''I don't know that I achieved any great success'' in this regard ''after I left the academic world.'' Graduated With Honors

Arthur Frank Burns was born in Stanislau, Austria, on April 27, 1904, the son of Nathan and Sarah Juran Burns. His parents brought him to this country when he was 10 and settled in Bayonne, N.J., where his father operated a small paint-contracting business.

Burns was born in Stanislau (now Ivano-Frankivsk), Austrian Poland (Galicia), a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1904 to Polish-Jewish parents, Sarah Juran and Nathan Burnseig, who worked as a house painter. He showed aptitude early in his childhood, when he translated the Talmud into Polish and Russian by age six and debated socialism at age nine.[2] In 1914, he immigrated to Bayonne, New Jersey, with his parents.[1] He graduated from Bayonne High School.[3]

At age 17, Burns enrolled in Columbia University on a scholarship offered by the university secretary. He worked in jobs ranging from postal clerk to shoe salesman during his time at Columbia as a student before earning his B.A. and M.A. in 1925, graduating Phi Beta Kappa.[4]

Young Arthur worked his way through school as a postal clerk, waiter, theater usher, dishwasher, oil tanker mess boy and salesman. He graduated with Phi Beta Kappa honors from Columbia University in 1925 and received a master's degree the same year.

In 1930, while working for his Ph.D. at Columbia and teaching economics at Rutgers, Mr. Burns came to the attention of Wesley Clair Mitchell, perhaps the most eminent American economist of his day and the founder and principal luminary of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

While still pursuing his career in teaching, Mr. Burns began his lifelong study of business cycles at the bureau and became Mr. Mitchell's protege.

Mr. Burns, who remained a professor at Rutgers until 1944, succeeded Mr. Mitchell as director of research of the National Bureau and served from 1945 to 1953. In 1945, he also became a professor at Columbia University.

Then, President Eisenhower, who while president of Columbia had met Mr. Burns, brought him to Washington. The political activity of members of the President's Council of Economic Advisers during the Administration of Harry S. Truman had turned Congress against the agency.

As chairman, Mr. Burns took the council out of politics and reconverted it into a general economics staff. It concentrated on giving technical advice and information to the President and on planning.

At the outset of his tenure he was faced with the minor economic contraction of 1953-54. In mid-1953, Mr. Burns urged President Eisenhower to spend more and tax less, with the result that the recession was relatively brief and mild. Restored Council's Prestige

After four years, Mr. Burns had restored the prestige of the council and won an established place for it in the Government. A nominal Democrat who had voted for Mr. Eisenhower, he achieved high respect from both parties in Congress.

By the end of 1956, Mr. Burns wanted to go back to research and teaching, and he returned to his professorship at Columbia. The National Bureau of Economic Research elected him its president.

When Mr. Nixon was elected President in 1968, he persuaded Mr. Burns to become his White House counselor as part of an understanding that Mr. Burns would be appointed chairman of the Federal Reserve when William McChesney Martin's term ended in early 1970.

During his brief tenure in the White House, Mr. Burns worked on a variety of projects, some unrelated to his economics background. He became Fed chairman on Feb. 1, 1970. In 1971, President Nixon, confronted by a mounting economic crisis, chose to impose full-scale wage and price controls while abandoning fixed exchange-rate values and ending the convertibility of dollars to gold. Mr. Burns, who had previously spoken out on the need to restrain wages, supported the wage and price controls but expressed doubt about ending the dollar-gold link.

Mr. Burns's most difficult time at the Federal Reserve came in 1974 and 1975. For the first time, his integrity was subjected to scrutiny, following a charge that he had made the money supply grow faster than was prudent, particularly in 1972, to aid President Nixon's re-election effort. In the elecpercent, compared with 6 percent durcreases were widely considered excessive.

''In my own judgment - and I think I know my own mind - one could not have been less political in a partisan sense than I was,'' Mr. Burns said in 1980. ''The election of 1972 had absolutely no influence on anything I did at the Fed.''

At the same time, Mr. Burns was being blamed - particularly by Democrats on Capitol Hill - for having brought on the 1974-75 recession by imposing a particularly tight hold on the money supply. Congressional Pressure

Shortly afterward, recession worries helped ignite another confrontation between the board and Capitol Hill as efforts were begun to make the secretive central bank disclose more of its policy decisions to Congress and, thereby, to the public. In 1975, by joint Congressional resolution, the Federal Reserve was forced for the first time to make public its target for the money supply.

These changes, as well as proposals for direct Congressional controls, were steadfastly opposed by Mr. Burns as an encroachment on the board's independence, although after the disclosure policy had been in effect for a year, he pronounced the change ''welcome.'' Nonetheless, he continued to resist further efforts to open the Federal Reserve to public scrutiny.

In the end, supporters and critics agreed that his tenacity helped defuse a major threat to the board's independence. His effort was aided by a tolerance for nearly endless discussion and debate, and at the Federal Reserve he often got his way by simply wearing out the opposition.

At the same time, Mr. Burns was intensifying his campaign to hold down the Federal budget deficit, an effort born of the belief that large Government borrowing helped to raise interest rates and made the Federal Reserve's job more difficult. Prophetic View on Inflation

In words that were to become prophetic, Mr. Burns warned in early 1976 that ''in the current inflationary environment, the conventional tools of stabilization policy cannot be counted on to restore full employment.''

After his departure from the Federal Reserve in 1978, when President Carter declined to reappoint him as chairman, Mr. Burns established a base in the American Enterprise Institute from which he continued to influence public policy, particularly as an adviser to Ronald Reagan.

In 1980, he served as founding chairman of the Committee to Fight Inflation, a gathering of a dozen prominent former economic policy makers united in their conviction that restrained policies were central to reducing inflation.

Mr. Burns married Helen Bernstein in 1930. They had two sons, David, a lawyer, and Joseph, an economist. The family spent summers at its farm in Ely, Vt., where Mr. Burns found artistic relaxation in painting pictures of New England homes. He is survived by his wife and two sons.

A private graveside service will be held on Sunday, a spokesman for the American Enterprise Institute said. A public memorial service will be held on July 22 at a site yet to be designated.

A version of this article appears in print on June 27, 1987, Section 1, Page 1 of the National edition of the New York Times Newspaper with the headline: Arthur F. Burns Is Dead at 83; A Shaper of Economic Policy & Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_F._Burns∼Politician. Burns was Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board and chairman of Council of economic advisers. From 1981 to 1985, Burns was the United States Ambassador to Germany.

Mr. Burns, who was 83 years old, died of complications following triple-bypass heart surgery in April.

''Arthur Burns was a staunch supporter of the Federal Reserve as an institution and a firm friend of many of us within it,'' said Paul A. Volcker, current chairman of the Federal Reserve, in a statement. He ''brought to his position force of personality, intellectual vigor and physical endurance.'' Served Under Eisenhower

Highly respected within the economics profession for his scholarship, Mr. Burns received greater public notice for his service in Washington, which began in 1953 when he became chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

His position of greatest influence was as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, from 1970 to 1978, one of the nation's most tumultuous and difficult economic periods.

From that post, as well as from all others, the Austrian-born Mr. Burns brought to bear an intellectual conservatism and a firm conviction of the dangers of inflation that was tempered by a commitment to a New Deal role for government in promoting economic prosperity.

''The only responsible course open to us,'' he once said, ''is to fight inflation tenaciously.'' But he promptly added: ''There is no way to turn back the clock and restore the environment of a bygone era. We can no longer cope with inflation by letting recessions run their course'' or by cutting programs that help the sick, the aged or the poor.

Although he served almost exclusively under Republican Presidents, Mr. Burns frequently made his mark by asserting a philosophical independence. On several issues, he clung to unpopular views that later became widely accepted, often by Democrats. PU FIRST AND LAST ADD BURNS OBIT pu first and last Burns Obit xxx by Democrats In 1969 and 1970, he advocated restraints on wage increases. In 1974 and 1975, when a deepening recession led to political moves to end the Federal Reserve Board's independence, Mr. Burns insisted that monetary restraint be maintained. And when Ronald Reagan suggested in 1980 and 1981 that people's ''expectations'' were important in determining economic performance, Mr. Burns reiterated his conviction that concrete action to reduce the budget deficit was more important than tax reductions aimed at expectations.

To all of his jobs, he brought a legendary capacity for hard work, an unfailingly courteous manner, a rarely questioned sense of integrity and a mind acknowledged even by his critics to be extraordinary.

Throughout, he was an unmistakable presence to millions of Americans, with his bushy gray hair parted down the middle, wire-rimmed spectacles, jutting pipe and precise, slightly nasal voice that maintained its soft-spoken tone under the most scathing questioning. Held Many Advisory Posts

Mr. Burns also served as President Richard M. Nixon's adviser on economic and other matters in 1969, as the Ambassador to West Germany from 1981 to 1985 and in an array of advisory posts. Since returning from Bonn, he had resumed his place as distinguished scholar in residence at the American Enterprise Institute.

As Ambassador, he quickly gained wide respect. West Germany's Chancellor, Helmut Schmidt, thanked President Reagan for sending him Mr. Burns, calling him ''one of the most knowledgeable financial and monetary experts in the world.'' The two were very close and Mr. Burns was considered a highly successful Ambassador.

Mr. Burns presided over the Federal Reserve at a time when the nation's inflation accelerated. In retrospect, the performance of the Federal Reserve in controlling the money supply during Mr. Burns's tenure received mixed grades. And if the public eventually awoke to the dangers of inflation, Mr. Burns's role in that educational process sometimes seemed indistinct.

''I devoted a good part of my life to trying to awaken the country to the dangers of inflation,'' he once said in a reflective moment. ''I don't know that I achieved any great success'' in this regard ''after I left the academic world.'' Graduated With Honors

Arthur Frank Burns was born in Stanislau, Austria, on April 27, 1904, the son of Nathan and Sarah Juran Burns. His parents brought him to this country when he was 10 and settled in Bayonne, N.J., where his father operated a small paint-contracting business.

Burns was born in Stanislau (now Ivano-Frankivsk), Austrian Poland (Galicia), a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1904 to Polish-Jewish parents, Sarah Juran and Nathan Burnseig, who worked as a house painter. He showed aptitude early in his childhood, when he translated the Talmud into Polish and Russian by age six and debated socialism at age nine.[2] In 1914, he immigrated to Bayonne, New Jersey, with his parents.[1] He graduated from Bayonne High School.[3]

At age 17, Burns enrolled in Columbia University on a scholarship offered by the university secretary. He worked in jobs ranging from postal clerk to shoe salesman during his time at Columbia as a student before earning his B.A. and M.A. in 1925, graduating Phi Beta Kappa.[4]

Young Arthur worked his way through school as a postal clerk, waiter, theater usher, dishwasher, oil tanker mess boy and salesman. He graduated with Phi Beta Kappa honors from Columbia University in 1925 and received a master's degree the same year.

In 1930, while working for his Ph.D. at Columbia and teaching economics at Rutgers, Mr. Burns came to the attention of Wesley Clair Mitchell, perhaps the most eminent American economist of his day and the founder and principal luminary of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

While still pursuing his career in teaching, Mr. Burns began his lifelong study of business cycles at the bureau and became Mr. Mitchell's protege.

Mr. Burns, who remained a professor at Rutgers until 1944, succeeded Mr. Mitchell as director of research of the National Bureau and served from 1945 to 1953. In 1945, he also became a professor at Columbia University.

Then, President Eisenhower, who while president of Columbia had met Mr. Burns, brought him to Washington. The political activity of members of the President's Council of Economic Advisers during the Administration of Harry S. Truman had turned Congress against the agency.

As chairman, Mr. Burns took the council out of politics and reconverted it into a general economics staff. It concentrated on giving technical advice and information to the President and on planning.

At the outset of his tenure he was faced with the minor economic contraction of 1953-54. In mid-1953, Mr. Burns urged President Eisenhower to spend more and tax less, with the result that the recession was relatively brief and mild. Restored Council's Prestige

After four years, Mr. Burns had restored the prestige of the council and won an established place for it in the Government. A nominal Democrat who had voted for Mr. Eisenhower, he achieved high respect from both parties in Congress.

By the end of 1956, Mr. Burns wanted to go back to research and teaching, and he returned to his professorship at Columbia. The National Bureau of Economic Research elected him its president.

When Mr. Nixon was elected President in 1968, he persuaded Mr. Burns to become his White House counselor as part of an understanding that Mr. Burns would be appointed chairman of the Federal Reserve when William McChesney Martin's term ended in early 1970.

During his brief tenure in the White House, Mr. Burns worked on a variety of projects, some unrelated to his economics background. He became Fed chairman on Feb. 1, 1970. In 1971, President Nixon, confronted by a mounting economic crisis, chose to impose full-scale wage and price controls while abandoning fixed exchange-rate values and ending the convertibility of dollars to gold. Mr. Burns, who had previously spoken out on the need to restrain wages, supported the wage and price controls but expressed doubt about ending the dollar-gold link.

Mr. Burns's most difficult time at the Federal Reserve came in 1974 and 1975. For the first time, his integrity was subjected to scrutiny, following a charge that he had made the money supply grow faster than was prudent, particularly in 1972, to aid President Nixon's re-election effort. In the elecpercent, compared with 6 percent durcreases were widely considered excessive.

''In my own judgment - and I think I know my own mind - one could not have been less political in a partisan sense than I was,'' Mr. Burns said in 1980. ''The election of 1972 had absolutely no influence on anything I did at the Fed.''

At the same time, Mr. Burns was being blamed - particularly by Democrats on Capitol Hill - for having brought on the 1974-75 recession by imposing a particularly tight hold on the money supply. Congressional Pressure

Shortly afterward, recession worries helped ignite another confrontation between the board and Capitol Hill as efforts were begun to make the secretive central bank disclose more of its policy decisions to Congress and, thereby, to the public. In 1975, by joint Congressional resolution, the Federal Reserve was forced for the first time to make public its target for the money supply.

These changes, as well as proposals for direct Congressional controls, were steadfastly opposed by Mr. Burns as an encroachment on the board's independence, although after the disclosure policy had been in effect for a year, he pronounced the change ''welcome.'' Nonetheless, he continued to resist further efforts to open the Federal Reserve to public scrutiny.

In the end, supporters and critics agreed that his tenacity helped defuse a major threat to the board's independence. His effort was aided by a tolerance for nearly endless discussion and debate, and at the Federal Reserve he often got his way by simply wearing out the opposition.

At the same time, Mr. Burns was intensifying his campaign to hold down the Federal budget deficit, an effort born of the belief that large Government borrowing helped to raise interest rates and made the Federal Reserve's job more difficult. Prophetic View on Inflation

In words that were to become prophetic, Mr. Burns warned in early 1976 that ''in the current inflationary environment, the conventional tools of stabilization policy cannot be counted on to restore full employment.''

After his departure from the Federal Reserve in 1978, when President Carter declined to reappoint him as chairman, Mr. Burns established a base in the American Enterprise Institute from which he continued to influence public policy, particularly as an adviser to Ronald Reagan.

In 1980, he served as founding chairman of the Committee to Fight Inflation, a gathering of a dozen prominent former economic policy makers united in their conviction that restrained policies were central to reducing inflation.

Mr. Burns married Helen Bernstein in 1930. They had two sons, David, a lawyer, and Joseph, an economist. The family spent summers at its farm in Ely, Vt., where Mr. Burns found artistic relaxation in painting pictures of New England homes. He is survived by his wife and two sons.

A private graveside service will be held on Sunday, a spokesman for the American Enterprise Institute said. A public memorial service will be held on July 22 at a site yet to be designated.

A version of this article appears in print on June 27, 1987, Section 1, Page 1 of the National edition of the New York Times Newspaper with the headline: Arthur F. Burns Is Dead at 83; A Shaper of Economic Policy & Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_F._Burns∼Politician. Burns was Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board and chairman of Council of economic advisers. From 1981 to 1985, Burns was the United States Ambassador to Germany.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement