He was appointed by President Lyndon Baines Johnson [in 1968] to the U.S. District Judge. Amoungst his achievements were that he changed the educational system of children as well as treatment of prisoners who housed the poorest and vunerable citizens This case [1972] was petitioned by an imate David Ruiz claiming alleged overcrowding and inhumane conditions. In a 188 page decision, Justice stated: "...prison officials tolerated rampant violence among inmates, guards and inmates who worked as guards under a generations-old system known as building tenders." In 2001, this matter was addressed before the Court. Reference [243 F3d 941 David Ruiz v. United States of America] for the complete ruling.

In 1977 he ruled that public schools to the child ren of illegal immigrants. He also provided bilingual education in rulings. The U. S. Supreme Court [1982] extended the ruling to include all schools - a foundation of national policy.

Justice ended federal oversight of the System in Texas in 2002.

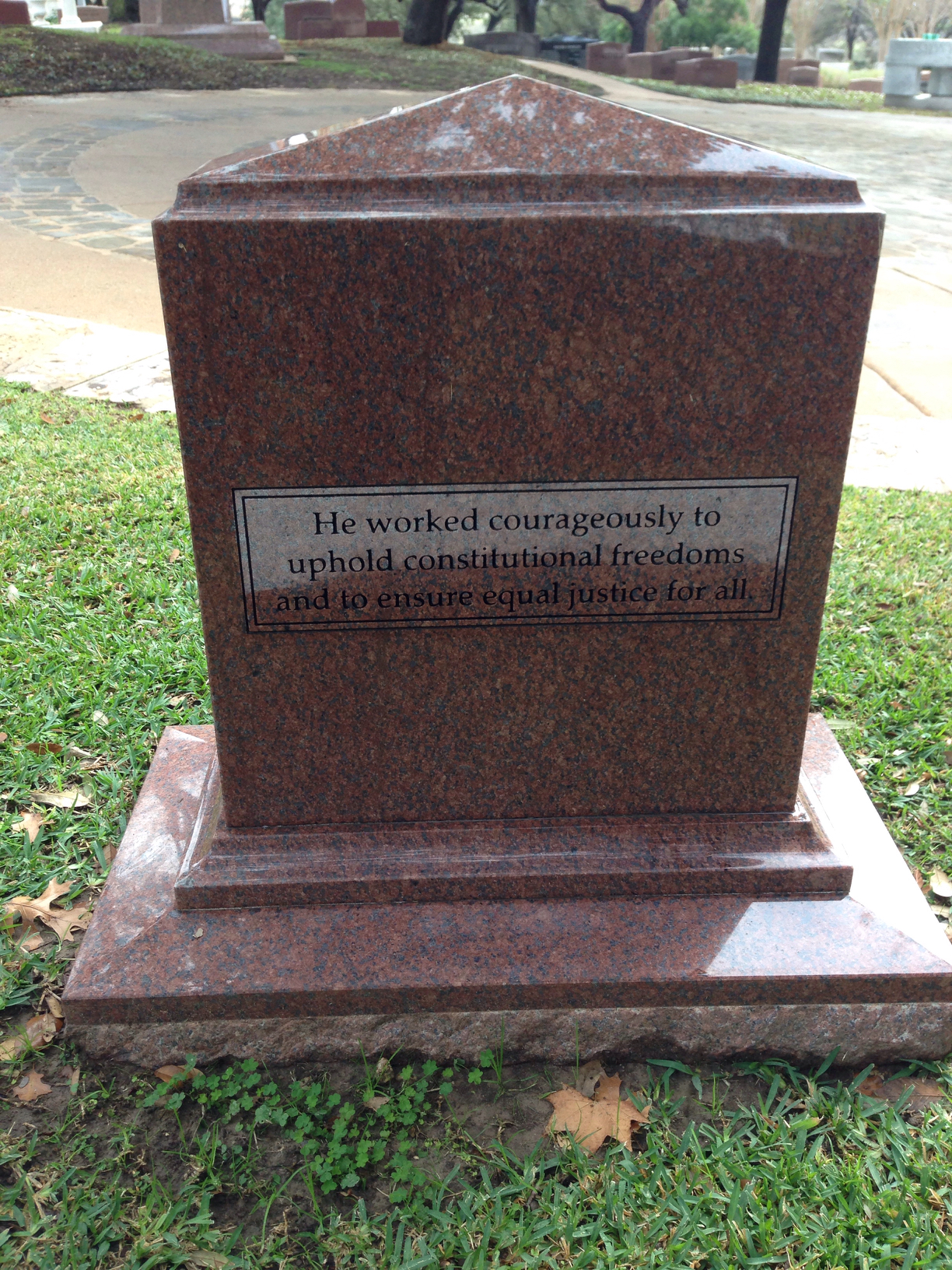

He is survived by his Wife, his daughter, Ellen and and a grandchild.∼His destiny was all in a name. "Judge Justice." William Wayne Justice was a giant in Texas history, the foreman of an audacious legal assembly line that churned out bulging packages of civil rights, equal justice and opportunities for the least among us. Justice, a soft-spoken federal judge who roared in his class action rulings on human rights over the past 41 years, died Tuesday in Austin, sources close to the family told the Tyler Morning Telegraph. He was 89 and was still serving as a U.S. district judge in Austin, although illness had kept him out of the office for months. Justice was a legend in his own time. The very mention of his made-for-Hollywood name could turn state officials and conservative taxpayers red with anger but melt the hearts of reform advocates fighting to better the lives of overlooked people who had no clout. People either thought "Judge Justice" was an oxymoron or simply redundant. But today, most agree that William Wayne Justice shoved Texas, against its will, into the mainstream of society. His legal compassion forever changed the lives of millions of schoolchildren, prisoners, minorities, immigrants and people with disabilities in Texas. He ordered the integration of public schools and public housing. He outlawed crowding, beatings and inhumane medical care in prisons and youth lockups. He ordered that community homes be provided to people with mental disabilities who were living in large institutions. He expanded voting opportunities. And that was just the tip of the docket. Justice also changed the landscape of public education. He ordered education for undocumented immigrant children and bilingual classrooms. And, back in the nonconformist hippie days of 1970, he ruled that bearded and long-haired students, including Vietnam veterans, had a right to attend public college. "I held that that was silly," he said in June 2009 while reminiscing about the old Tyler Junior College rule forbidding long hair on male students. Some of the class action cases, many of which were the largest institutional reform lawsuits in America, dragged on for decades and outlasted a long string of Texas governors, lawyers and even some of the original plaintiffs. All the while, the genteel and courtly judge slept easily at night and always kept his number listed in the public telephone directory in the conservative East Texas town of Tyler, where he served for 30 years before moving to Austin's federal court in 1998 to be closer to his daughter. He chose to ignore the many death threats, mountains of hate mail and cold shoulders from strangers and close neighbors alike. He recently recalled walking into a Tyler gas station after striking down the long-hair ban. "The place went silent," he said, and the old-timers stared into their coffee cups. It was just another daily snub for a man who challenged people's prejudices. One of the coffee drinkers looked out the window, saw a couple of long-haired young men and said, "They ought to be in the penitentiary." William Wayne Justice was "perhaps the single most influential agent for change in 20th-century Texas history," according to his official biographer, Frank Kemerer, who was a professor at the University of North Texas for almost 30 years. "Through a series of momentous judicial decisions, his influence would sweep across the Texas landscape far beyond the geographic boundaries of his court and out into the nation," he wrote in "William Wayne Justice: A Judicial Biography" (University of Texas Press). Justice was at the top of the list of so-called activist judges who, as a general group, are often accused by former President George W. Bush and other legal conservatives of interpreting the U.S. Constitution too expansively. But Justice took to heart a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1958 that, in essence, the Constitution and its amendments are "not static" and must draw "meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society." "I was never underprivileged, but I have human feelings. If you see someone in distress, well, you want to help them if you can," Justice told the American-Statesman in 2006. "I hope people remember me for someone trying to do justice. That's what I've tried to do." The late Barbara Jordan, the first black woman from the South to serve in the U.S. Congress when she was elected from Texas in 1972, once said Justice "helped officials in Texas state government see their duty clearly." It may be difficult for Texas newcomers or younger generations to picture the slight, humble man with the lopsided grin who worked out regularly at the YMCA as someone who once was so despised by many Texans that bumper stickers called him the "most hated man in Texas." Thirty of his more than 40 years as a federal judge were spent in Tyler, where more than 10,000 of the 65,000 residents signed a petition to try to have him impeached. Repair people refused to work on his home, and when he entered a restaurant, other patrons walked out. But today's 21st-century Texas is different from the segregation and close-minded thinking that pervaded the state in 1968, when President Lyndon Johnson appointed Justice to the federal bench in East Texas, where the judge was born and raised. Justice's courtroom in Tyler was just 35 miles from the smaller and more liberal town of Athens, where he was born on Feb. 25, 1920. Justice's father had been a flamboyant and highly successful criminal lawyer in Athens who added his son's name to the law office door when the boy was only 7. William Wayne Justice, a lifelong bookworm and sports enthusiast, knew he wanted to be a lawyer. He attended undergraduate school at the University of Texas and graduated from its law school in early 1942. He then served nearly four years in the Army during World War II, ending up in India as a first lieutenant. He practiced law with his father during the 1940s and 1950s. He was swept off his feet in the mid-1940s by a beautiful young woman named Sue Rowan, who became his wife on March 16, 1947. They had one child, Ellen, who lives in Austin with her husband. While practicing law, Justice served two terms in the part-time position of Athens city attorney. Both Wayne and Sue Justice became active in Democratic politics and befriended the late U.S. senator from Texas, liberal Ralph Yarborough. In 1961, Justice was named U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Texas. He was reappointed in 1966. By the time Justice was sworn in as a federal judge two years later, he had amassed broad experience in the courtroom. Though he had never been the victim of discrimination or deprivation, he had been introduced to the downtrodden world and woes of the have-nots through his legal work, his parents' guidance and the views of his humanitarian wife. In addition, a series of childhood illnesses that he overcame, such as chronic whooping cough, had given him valuable insight into the suffering of the underdog. "It's when you're weak like that, you get picked on, and I guess that's where I developed an attitude where I can understand the people that are oppressed," he told the American-Statesman in 2006. Justice's ascension to the federal bench came at a time of social revolution and upheaval in America, and he was ready. It didn't take long for him to begin roiling the status quo in rulings that were received like bombshells from the bench. He threw himself into one of the early cases filed in his court, the dispute about whether Tyler Junior College could require male students to have short hair, trimmed mustaches and no beards to ensure a peaceful campus. "Unconstitutional," Justice quickly ruled. The best and worst of men throughout history sported hairstyles popular in their day, he said. Further, he noted, nearly every delegate to the Constitutional Convention would have be

∼UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE.

He graduated from the University of Texas School of Law in 1942. He joined the United States Army where he served in India during World War II. He began practicing law in Athens, Texas with his attorney father in 1946. He and his father were known as a voice for the disadvantaged. He served as City Attorney in Athens for eight years. Then in 1961, he was selected by President John F. Kennedy to serve as the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Texas. In 1968, he was appointed to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas by President Lyndon B. Johnson. In 1998 he took senior status and later sat by designation in the Western District of Texas. In November 1970, he ordered the Texas Education Agency to begin desegregating the Texas public schools system. His decision was upheld on appeal by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. In 1982 he made it manditory so that children of undocumented immigrants could attend public schools through grade 12, tuition free.

He was appointed by President Lyndon Baines Johnson [in 1968] to the U.S. District Judge. Amoungst his achievements were that he changed the educational system of children as well as treatment of prisoners who housed the poorest and vunerable citizens This case [1972] was petitioned by an imate David Ruiz claiming alleged overcrowding and inhumane conditions. In a 188 page decision, Justice stated: "...prison officials tolerated rampant violence among inmates, guards and inmates who worked as guards under a generations-old system known as building tenders." In 2001, this matter was addressed before the Court. Reference [243 F3d 941 David Ruiz v. United States of America] for the complete ruling.

In 1977 he ruled that public schools to the child ren of illegal immigrants. He also provided bilingual education in rulings. The U. S. Supreme Court [1982] extended the ruling to include all schools - a foundation of national policy.

Justice ended federal oversight of the System in Texas in 2002.

He is survived by his Wife, his daughter, Ellen and and a grandchild.∼His destiny was all in a name. "Judge Justice." William Wayne Justice was a giant in Texas history, the foreman of an audacious legal assembly line that churned out bulging packages of civil rights, equal justice and opportunities for the least among us. Justice, a soft-spoken federal judge who roared in his class action rulings on human rights over the past 41 years, died Tuesday in Austin, sources close to the family told the Tyler Morning Telegraph. He was 89 and was still serving as a U.S. district judge in Austin, although illness had kept him out of the office for months. Justice was a legend in his own time. The very mention of his made-for-Hollywood name could turn state officials and conservative taxpayers red with anger but melt the hearts of reform advocates fighting to better the lives of overlooked people who had no clout. People either thought "Judge Justice" was an oxymoron or simply redundant. But today, most agree that William Wayne Justice shoved Texas, against its will, into the mainstream of society. His legal compassion forever changed the lives of millions of schoolchildren, prisoners, minorities, immigrants and people with disabilities in Texas. He ordered the integration of public schools and public housing. He outlawed crowding, beatings and inhumane medical care in prisons and youth lockups. He ordered that community homes be provided to people with mental disabilities who were living in large institutions. He expanded voting opportunities. And that was just the tip of the docket. Justice also changed the landscape of public education. He ordered education for undocumented immigrant children and bilingual classrooms. And, back in the nonconformist hippie days of 1970, he ruled that bearded and long-haired students, including Vietnam veterans, had a right to attend public college. "I held that that was silly," he said in June 2009 while reminiscing about the old Tyler Junior College rule forbidding long hair on male students. Some of the class action cases, many of which were the largest institutional reform lawsuits in America, dragged on for decades and outlasted a long string of Texas governors, lawyers and even some of the original plaintiffs. All the while, the genteel and courtly judge slept easily at night and always kept his number listed in the public telephone directory in the conservative East Texas town of Tyler, where he served for 30 years before moving to Austin's federal court in 1998 to be closer to his daughter. He chose to ignore the many death threats, mountains of hate mail and cold shoulders from strangers and close neighbors alike. He recently recalled walking into a Tyler gas station after striking down the long-hair ban. "The place went silent," he said, and the old-timers stared into their coffee cups. It was just another daily snub for a man who challenged people's prejudices. One of the coffee drinkers looked out the window, saw a couple of long-haired young men and said, "They ought to be in the penitentiary." William Wayne Justice was "perhaps the single most influential agent for change in 20th-century Texas history," according to his official biographer, Frank Kemerer, who was a professor at the University of North Texas for almost 30 years. "Through a series of momentous judicial decisions, his influence would sweep across the Texas landscape far beyond the geographic boundaries of his court and out into the nation," he wrote in "William Wayne Justice: A Judicial Biography" (University of Texas Press). Justice was at the top of the list of so-called activist judges who, as a general group, are often accused by former President George W. Bush and other legal conservatives of interpreting the U.S. Constitution too expansively. But Justice took to heart a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in 1958 that, in essence, the Constitution and its amendments are "not static" and must draw "meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society." "I was never underprivileged, but I have human feelings. If you see someone in distress, well, you want to help them if you can," Justice told the American-Statesman in 2006. "I hope people remember me for someone trying to do justice. That's what I've tried to do." The late Barbara Jordan, the first black woman from the South to serve in the U.S. Congress when she was elected from Texas in 1972, once said Justice "helped officials in Texas state government see their duty clearly." It may be difficult for Texas newcomers or younger generations to picture the slight, humble man with the lopsided grin who worked out regularly at the YMCA as someone who once was so despised by many Texans that bumper stickers called him the "most hated man in Texas." Thirty of his more than 40 years as a federal judge were spent in Tyler, where more than 10,000 of the 65,000 residents signed a petition to try to have him impeached. Repair people refused to work on his home, and when he entered a restaurant, other patrons walked out. But today's 21st-century Texas is different from the segregation and close-minded thinking that pervaded the state in 1968, when President Lyndon Johnson appointed Justice to the federal bench in East Texas, where the judge was born and raised. Justice's courtroom in Tyler was just 35 miles from the smaller and more liberal town of Athens, where he was born on Feb. 25, 1920. Justice's father had been a flamboyant and highly successful criminal lawyer in Athens who added his son's name to the law office door when the boy was only 7. William Wayne Justice, a lifelong bookworm and sports enthusiast, knew he wanted to be a lawyer. He attended undergraduate school at the University of Texas and graduated from its law school in early 1942. He then served nearly four years in the Army during World War II, ending up in India as a first lieutenant. He practiced law with his father during the 1940s and 1950s. He was swept off his feet in the mid-1940s by a beautiful young woman named Sue Rowan, who became his wife on March 16, 1947. They had one child, Ellen, who lives in Austin with her husband. While practicing law, Justice served two terms in the part-time position of Athens city attorney. Both Wayne and Sue Justice became active in Democratic politics and befriended the late U.S. senator from Texas, liberal Ralph Yarborough. In 1961, Justice was named U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Texas. He was reappointed in 1966. By the time Justice was sworn in as a federal judge two years later, he had amassed broad experience in the courtroom. Though he had never been the victim of discrimination or deprivation, he had been introduced to the downtrodden world and woes of the have-nots through his legal work, his parents' guidance and the views of his humanitarian wife. In addition, a series of childhood illnesses that he overcame, such as chronic whooping cough, had given him valuable insight into the suffering of the underdog. "It's when you're weak like that, you get picked on, and I guess that's where I developed an attitude where I can understand the people that are oppressed," he told the American-Statesman in 2006. Justice's ascension to the federal bench came at a time of social revolution and upheaval in America, and he was ready. It didn't take long for him to begin roiling the status quo in rulings that were received like bombshells from the bench. He threw himself into one of the early cases filed in his court, the dispute about whether Tyler Junior College could require male students to have short hair, trimmed mustaches and no beards to ensure a peaceful campus. "Unconstitutional," Justice quickly ruled. The best and worst of men throughout history sported hairstyles popular in their day, he said. Further, he noted, nearly every delegate to the Constitutional Convention would have be

∼UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE.

He graduated from the University of Texas School of Law in 1942. He joined the United States Army where he served in India during World War II. He began practicing law in Athens, Texas with his attorney father in 1946. He and his father were known as a voice for the disadvantaged. He served as City Attorney in Athens for eight years. Then in 1961, he was selected by President John F. Kennedy to serve as the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Texas. In 1968, he was appointed to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas by President Lyndon B. Johnson. In 1998 he took senior status and later sat by designation in the Western District of Texas. In November 1970, he ordered the Texas Education Agency to begin desegregating the Texas public schools system. His decision was upheld on appeal by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. In 1982 he made it manditory so that children of undocumented immigrants could attend public schools through grade 12, tuition free.