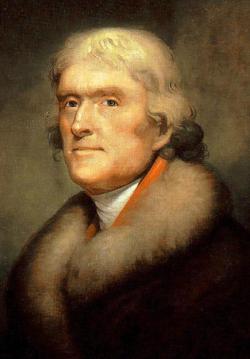

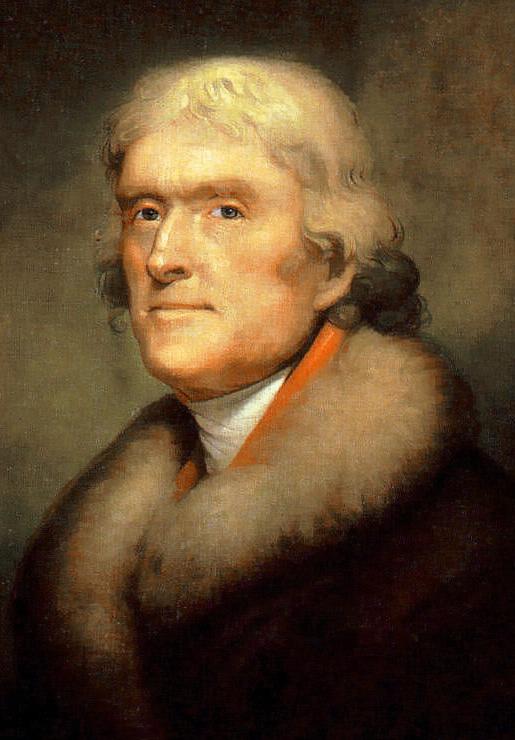

3rd United States President, 2nd United States Vice President, Virginia Governor, Declaration of Independence Signer. A philosopher, statesman, scholar, attorney, planter, architect, violinist, writer, archaeologist, and natural scientist. He wished to be remembered as the author of the Declaration of Independence and of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom as well as the founder of the University of Virginia. Born of a moderately well-off planter family, Jefferson was early imbued by his father, Peter, with a love of both nature and books. His mother, Jane, was a descendent of the noted Randolph family of Virginia. He studied with two private schoolmasters, the Reverend William Douglas and the Reverend James Maury; the latter was a plaintiff in the famous Parson's Cause case, for whom he was to have profound respect all his life. After Peter Jefferson's sudden death in 1757 left him "completely on his own," he entered the College of William and Mary in 1760 and applied himself to his studies while beginning the collection of his eventually-massive library. (Jefferson's meticulous record of his purchases, in which he noted not only the book, but the edition and printing number, has enabled modern scholars to reconstruct his library at Monticello.) While at college, he met and frequently dined with three men who taught him Enlightenment Philosophy and altered the course of his thought and life: Governor Francis Fauquier, attorney and scholar George Wythe, and professor William Small. The March 1764 rejection of his romantic advances to Rebecca Burwell triggered the first bout of Jefferson's famous headaches which were to reoccur in times of stress until his 1809 retirement from the White House. The precise diagnosis remains unclear, with some authorities speculating a migraine variant, though others say he suffered from tension headaches. He later read law with Wythe, was admitted to the Virginia Bar in 1767, and, despite being shy and a poor public speaker, was a successful attorney in the various county courts on the judicial circuit. (When compared with his then-friend, and sometimes legal rival, it was said that "Patrick Henry speaks to the heart, Jefferson to the mind.") Jefferson was elected to the House of Burgesses from Albemarle County, Virginia, in 1768 and while in Williamsburg he met, around 1770, a wealthy widow named Martha Wayles Skelton. The couple married on New Years Day in 1772 and set up life at Jefferson's new home at Monticello, which was still under construction. "Patty" Jefferson was never very healthy, and six pregnancies in ten years (only daughters Patsy and Polly would survive to adulthood), completely destroyed her strength. She died in 1782, leaving Jefferson prostrated for weeks. According to legend, he promised her on her deathbed that he would never remarry, and, whatever the truth of that story, he never did. He published "A Summary View of the Rights of British America" in 1774, setting forth his view that loyalty was owed only to the Crown, not to Parliament. This was much further on the road to independence..."the God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time"...than the public was then ready to travel. After serving in the Continental Congress of 1775, he was returned in 1776 and tasked with writing the Declaration of Independence after Benjamin Franklin declined as he would not write a document subject to the editing of others. The work was not generally known as Jefferson's until later; he resented certain of the revisions for the remainder his life, and the precise meanings of some phrases shall be debated eternally. Returning home, he was assigned the job, along with Edmund Pendleton and George Wythe, of revising the laws of Virginia; success mixed with failure. He got rid of entail and primogeniture (laws restricting inheritance to first-born sons), and limited capital punishment (which he had wanted to abolish), but his 1779 Bill Establishing Religious Freedom was stalled until James Madison pushed it through in 1786. Jefferson served two thoroughly-miserable one-year terms as Governor of Virginia, during which time the Capital was moved to Richmond. An investigation of his conduct in escaping from British troops resulted in the final, permanent, and probably unjustified, rupture of his relationship with Patrick Henry. In 1780, Jefferson received one of his proudest honors, election to the Philadelphia-based American Philosophical Society, of which he was to serve as president from 1797 until 1815. In 1782, he began work on "Notes on the State of Virginia," his only published book, which was released in France in 1785 and in England in 1787. In 1785, he was sent to Paris as the American Minister where through correspondence, he kept up on events. Of Shay's 1787 Rebellion, he wrote that "the tree of liberty must be refreshed with the blood of patriots and tyrants from time to time." Being in France, he was denied an active hand in the framing of the Constitution. In August of 1786, he met, thru painter John Trumbull, the beautiful married artist Maria Cosway, with either an illicit romance or merely an improper friendship of short duration resulting. During one of their escapades Jefferson fractured his right wrist and had problems with it ever after. The end of the affair brought forth the famous "My Head and My Heart" letter, still one of Jefferson's most studied writings. For whatever reason, the relationship was not renewed on Maria's subsequent visits to Paris, though letters were exchanged over the years. Returning to America in 1789 for what he thought would be a brief stay, he was appointed the first Secretary of State and was to be completely unhappy in the job. His document on weights and measures, which would have put the United States on the metric system, was rejected. His successful 1790 mediation of the assumption-location controversy between Madison and Hamilton, which placed the nation's Capital in its present location in Washington, D.C., while making the federal government responsible for the states' Revolutionary War debts, led to another lifelong regret. His advice to meet the Barbary Pirates with military force rather than with negotiation and ransom would have to wait until he was President. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton frequently undercut him by secretly feeding classified information to British representative George Hammond. The 1793 "Citizen Genet Affair" strained his devotion to France. Hatred for Hamilton and a growing rupture with John Adams, and, to a lesser extent, George Washington, resulted in his founding, with Madison, of the Republican Party. Jefferson retired to Monticello at the end of 1793, but was called upon to run for President in 1796. Getting the second-highest vote total, he became Adams' Vice President and was again miserable, forced to fight the Alien and Sedition Acts at personal risk. In 1800, he once more opposed Adams in one of the nastiest campaign in American history. Called a "howling atheist," he remained silent. (Jefferson's religion, like much else, was private, with his views known only to him. A lifelong Anglican, he was not an atheist, and was probably either a Deist or a Unitarian.) Accused by muckraker James Callender of producing mulatto children with his slave Sally Hemings, he also kept silent. While much invective has been spewed and untold quantities of ink committed to paper, more than two centuries of scholarship has failed to find the slightest hard evidence of a Tom-and-Sally sexual relationship. Narrowly defeating Adams, and after a House of Representatives fight with his running mate, Aaron Burr, he became the third President of the United States. Following a conciliatory inaugural address, his first term was filled with triumphs including the Louisiana Purchase and the starting of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. This second term saw mostly trouble: the Aaron Burr treason trial of 1807 transformed his relations with John Marshall from courteous mutual dislike to blind hatred, and the failed trade embargo against England. Retiring to Monticello, he renewed, at the behest of Dr. Benjamin Rush, his friendship and correspondence with John Adams, with the letters continuing to provide a treasure-trove for students of both men. After paying his father-in-law's debts, Jefferson was essentially impoverished for his last 50 years, spending too much on Monticello, lavish entertaining, food, wine, and, mostly, books. In 1814, he negotiated the sale of his 6,487-volume library for $23,950 to replace the Library of Congress which had been burned by the British in 1814 during the War of 1812, though stating "I cannot live without books," he was to acquire approximately another 1,000 prior to his death. In 1819, Jefferson saw his final dream realized when the Legislature approved the University of Virginia. He designed the buildings, hired the professors, saw the first students admitted in 1825, and even invited them two at a time to his home for dinner, with a young Edgar Allan Poe receiving suggestions for future reading. Reasonably healthy, albeit with some chronic urinary problems, for what was then considered far-advanced age, he functioned fairly well until his last few months. He died on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence (the same day as former President John Adams) of a chronic gastric problem, probably cancer. He continues to be the subject of countless books, the definitive biographies being Dumas Malone's six volume "Jefferson and His Time" (1948 through 1981) and Merrill Peterson's "Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation" (1970). His tombstone is a replacement, the original having been destroyed by souvenir hunters. Jefferson left a multitude of quotes and while certainly no single one can define such a multifaceted man, this one stands out: "I have sworn on the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man." On April 29, 1962, President John F. Kennedy held a dinner at the White House, honoring Nobel Prize winners from the Western Hemisphere. In the President's opening remarks, he famously stated: "I want to tell you how welcome you are to the White House. I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone."

3rd United States President, 2nd United States Vice President, Virginia Governor, Declaration of Independence Signer. A philosopher, statesman, scholar, attorney, planter, architect, violinist, writer, archaeologist, and natural scientist. He wished to be remembered as the author of the Declaration of Independence and of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom as well as the founder of the University of Virginia. Born of a moderately well-off planter family, Jefferson was early imbued by his father, Peter, with a love of both nature and books. His mother, Jane, was a descendent of the noted Randolph family of Virginia. He studied with two private schoolmasters, the Reverend William Douglas and the Reverend James Maury; the latter was a plaintiff in the famous Parson's Cause case, for whom he was to have profound respect all his life. After Peter Jefferson's sudden death in 1757 left him "completely on his own," he entered the College of William and Mary in 1760 and applied himself to his studies while beginning the collection of his eventually-massive library. (Jefferson's meticulous record of his purchases, in which he noted not only the book, but the edition and printing number, has enabled modern scholars to reconstruct his library at Monticello.) While at college, he met and frequently dined with three men who taught him Enlightenment Philosophy and altered the course of his thought and life: Governor Francis Fauquier, attorney and scholar George Wythe, and professor William Small. The March 1764 rejection of his romantic advances to Rebecca Burwell triggered the first bout of Jefferson's famous headaches which were to reoccur in times of stress until his 1809 retirement from the White House. The precise diagnosis remains unclear, with some authorities speculating a migraine variant, though others say he suffered from tension headaches. He later read law with Wythe, was admitted to the Virginia Bar in 1767, and, despite being shy and a poor public speaker, was a successful attorney in the various county courts on the judicial circuit. (When compared with his then-friend, and sometimes legal rival, it was said that "Patrick Henry speaks to the heart, Jefferson to the mind.") Jefferson was elected to the House of Burgesses from Albemarle County, Virginia, in 1768 and while in Williamsburg he met, around 1770, a wealthy widow named Martha Wayles Skelton. The couple married on New Years Day in 1772 and set up life at Jefferson's new home at Monticello, which was still under construction. "Patty" Jefferson was never very healthy, and six pregnancies in ten years (only daughters Patsy and Polly would survive to adulthood), completely destroyed her strength. She died in 1782, leaving Jefferson prostrated for weeks. According to legend, he promised her on her deathbed that he would never remarry, and, whatever the truth of that story, he never did. He published "A Summary View of the Rights of British America" in 1774, setting forth his view that loyalty was owed only to the Crown, not to Parliament. This was much further on the road to independence..."the God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time"...than the public was then ready to travel. After serving in the Continental Congress of 1775, he was returned in 1776 and tasked with writing the Declaration of Independence after Benjamin Franklin declined as he would not write a document subject to the editing of others. The work was not generally known as Jefferson's until later; he resented certain of the revisions for the remainder his life, and the precise meanings of some phrases shall be debated eternally. Returning home, he was assigned the job, along with Edmund Pendleton and George Wythe, of revising the laws of Virginia; success mixed with failure. He got rid of entail and primogeniture (laws restricting inheritance to first-born sons), and limited capital punishment (which he had wanted to abolish), but his 1779 Bill Establishing Religious Freedom was stalled until James Madison pushed it through in 1786. Jefferson served two thoroughly-miserable one-year terms as Governor of Virginia, during which time the Capital was moved to Richmond. An investigation of his conduct in escaping from British troops resulted in the final, permanent, and probably unjustified, rupture of his relationship with Patrick Henry. In 1780, Jefferson received one of his proudest honors, election to the Philadelphia-based American Philosophical Society, of which he was to serve as president from 1797 until 1815. In 1782, he began work on "Notes on the State of Virginia," his only published book, which was released in France in 1785 and in England in 1787. In 1785, he was sent to Paris as the American Minister where through correspondence, he kept up on events. Of Shay's 1787 Rebellion, he wrote that "the tree of liberty must be refreshed with the blood of patriots and tyrants from time to time." Being in France, he was denied an active hand in the framing of the Constitution. In August of 1786, he met, thru painter John Trumbull, the beautiful married artist Maria Cosway, with either an illicit romance or merely an improper friendship of short duration resulting. During one of their escapades Jefferson fractured his right wrist and had problems with it ever after. The end of the affair brought forth the famous "My Head and My Heart" letter, still one of Jefferson's most studied writings. For whatever reason, the relationship was not renewed on Maria's subsequent visits to Paris, though letters were exchanged over the years. Returning to America in 1789 for what he thought would be a brief stay, he was appointed the first Secretary of State and was to be completely unhappy in the job. His document on weights and measures, which would have put the United States on the metric system, was rejected. His successful 1790 mediation of the assumption-location controversy between Madison and Hamilton, which placed the nation's Capital in its present location in Washington, D.C., while making the federal government responsible for the states' Revolutionary War debts, led to another lifelong regret. His advice to meet the Barbary Pirates with military force rather than with negotiation and ransom would have to wait until he was President. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton frequently undercut him by secretly feeding classified information to British representative George Hammond. The 1793 "Citizen Genet Affair" strained his devotion to France. Hatred for Hamilton and a growing rupture with John Adams, and, to a lesser extent, George Washington, resulted in his founding, with Madison, of the Republican Party. Jefferson retired to Monticello at the end of 1793, but was called upon to run for President in 1796. Getting the second-highest vote total, he became Adams' Vice President and was again miserable, forced to fight the Alien and Sedition Acts at personal risk. In 1800, he once more opposed Adams in one of the nastiest campaign in American history. Called a "howling atheist," he remained silent. (Jefferson's religion, like much else, was private, with his views known only to him. A lifelong Anglican, he was not an atheist, and was probably either a Deist or a Unitarian.) Accused by muckraker James Callender of producing mulatto children with his slave Sally Hemings, he also kept silent. While much invective has been spewed and untold quantities of ink committed to paper, more than two centuries of scholarship has failed to find the slightest hard evidence of a Tom-and-Sally sexual relationship. Narrowly defeating Adams, and after a House of Representatives fight with his running mate, Aaron Burr, he became the third President of the United States. Following a conciliatory inaugural address, his first term was filled with triumphs including the Louisiana Purchase and the starting of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. This second term saw mostly trouble: the Aaron Burr treason trial of 1807 transformed his relations with John Marshall from courteous mutual dislike to blind hatred, and the failed trade embargo against England. Retiring to Monticello, he renewed, at the behest of Dr. Benjamin Rush, his friendship and correspondence with John Adams, with the letters continuing to provide a treasure-trove for students of both men. After paying his father-in-law's debts, Jefferson was essentially impoverished for his last 50 years, spending too much on Monticello, lavish entertaining, food, wine, and, mostly, books. In 1814, he negotiated the sale of his 6,487-volume library for $23,950 to replace the Library of Congress which had been burned by the British in 1814 during the War of 1812, though stating "I cannot live without books," he was to acquire approximately another 1,000 prior to his death. In 1819, Jefferson saw his final dream realized when the Legislature approved the University of Virginia. He designed the buildings, hired the professors, saw the first students admitted in 1825, and even invited them two at a time to his home for dinner, with a young Edgar Allan Poe receiving suggestions for future reading. Reasonably healthy, albeit with some chronic urinary problems, for what was then considered far-advanced age, he functioned fairly well until his last few months. He died on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence (the same day as former President John Adams) of a chronic gastric problem, probably cancer. He continues to be the subject of countless books, the definitive biographies being Dumas Malone's six volume "Jefferson and His Time" (1948 through 1981) and Merrill Peterson's "Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation" (1970). His tombstone is a replacement, the original having been destroyed by souvenir hunters. Jefferson left a multitude of quotes and while certainly no single one can define such a multifaceted man, this one stands out: "I have sworn on the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man." On April 29, 1962, President John F. Kennedy held a dinner at the White House, honoring Nobel Prize winners from the Western Hemisphere. In the President's opening remarks, he famously stated: "I want to tell you how welcome you are to the White House. I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone."

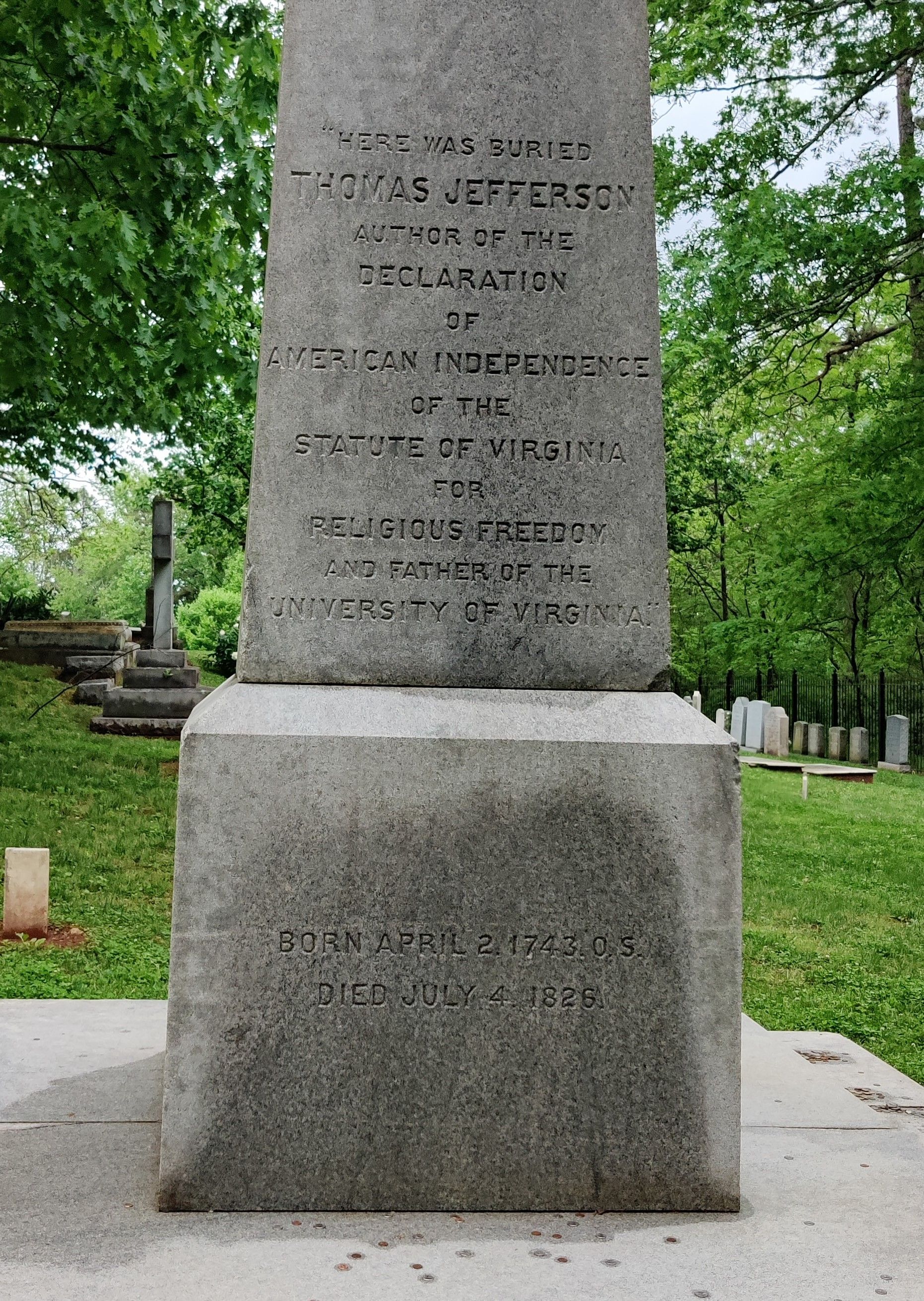

Inscription

"HERE WAS BURIED

THOMAS JEFFERSON

AUTHOR OF THE

DECLARATION

OF

AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE

OF THE

STATUTE OF VIRGINIA

FOR

RELIGIOUS FREEDOM

AND FATHER OF THE

UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA."

BORN APRIL 2, 1743. O.S.

DIED JULY 4, 1826.

Family Members

-

Jane Jefferson

1740–1765

-

![]()

Mary Jefferson Bolling

1741–1803

-

![]()

Thomas Jefferson

1743–1826

-

Elizabeth Jefferson

1744–1774

-

![]()

Martha Jefferson Carr

1746–1811

-

Peter Field Jefferson

1748–1748

-

Unnamed Son Jefferson

1750–1750

-

![]()

Lucy Jefferson Lewis

1752–1810

-

Anna Scott Jefferson Marks

1755–1828

-

Randolph Jefferson

1755–1815

-

![]()

Patsy Jefferson Randolph

1772–1836

-

Jane Randolph Jefferson

1774–1775

-

Infant Son Jefferson

1777–1777

-

![]()

Mary "Maria" Jefferson Eppes

1778–1804

-

Lucy Elizabeth Jefferson I

1780–1781

-

Lucy Elizabeth Jefferson II

1782–1784

-

William Beverly Hemings

1798 – unknown

-

Harriet Hemings

1801 – unknown

-

James Madison Hemings

1805–1877

-

![]()

Eston Hemings Jefferson

1808–1856

Advertisement

See more Jefferson memorials in:

Records on Ancestry

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement