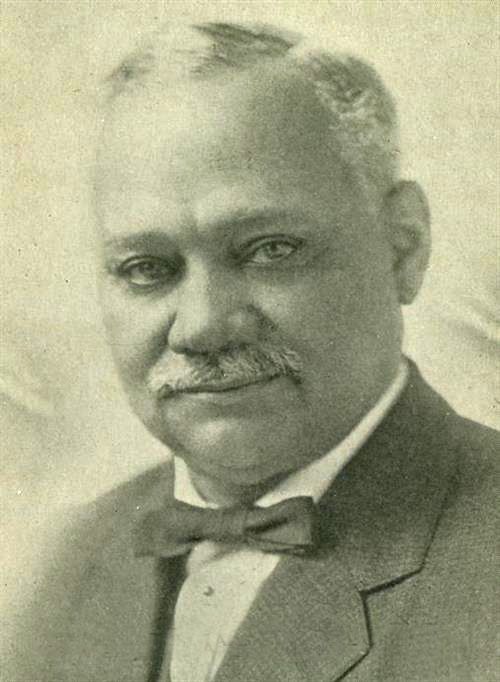

Scipio Jones was born to a slave, Jemmima Jones, in 1863 in the area of Tulip (Dallas County). His father is generally considered to be Dr. Sanford Reamey, a prominent citizen of Tulip and the owner of Jemmima at the time of Jones’s birth. Jones attended schools for African Americans in the Tulip area and later moved to Little Rock, attending Walden Seminary (now Philander Smith College), where he completed the four-year college preparatory course in only three years. He then attended Bethel Institute (now Shorter College) in North Little Rock (Pulaski County), from which he received a bachelor’s degree in 1885. During the next four years, Jones taught public school while studying law on his own time. On June 15, 1889, Jones passed the bar. His credentials were accepted by the Supreme Court of Arkansas in 1900 and by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1905.

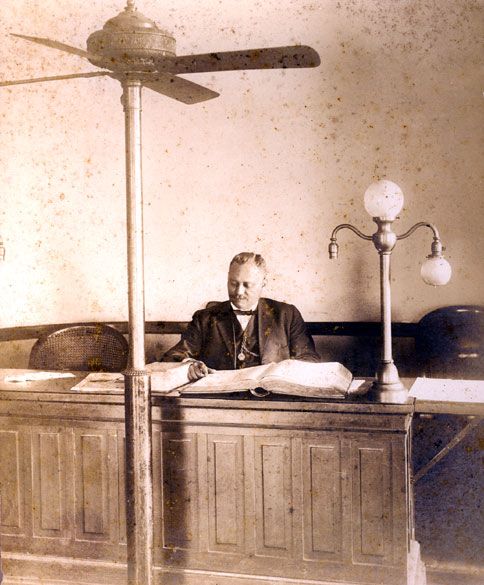

Jones practiced law in Little Rock for the rest of his life. He frequently represented indigent citizens and worked to correct abuse and injustice in Arkansas’s penal system; Jones twice served in temporary capacity as a judge. He was elected a special judge to hear a case in the Little Rock Municipal Court when the regular judge disqualified himself. In 1924, Jones was elected a special chancellor in Pulaski County Chancery Court.

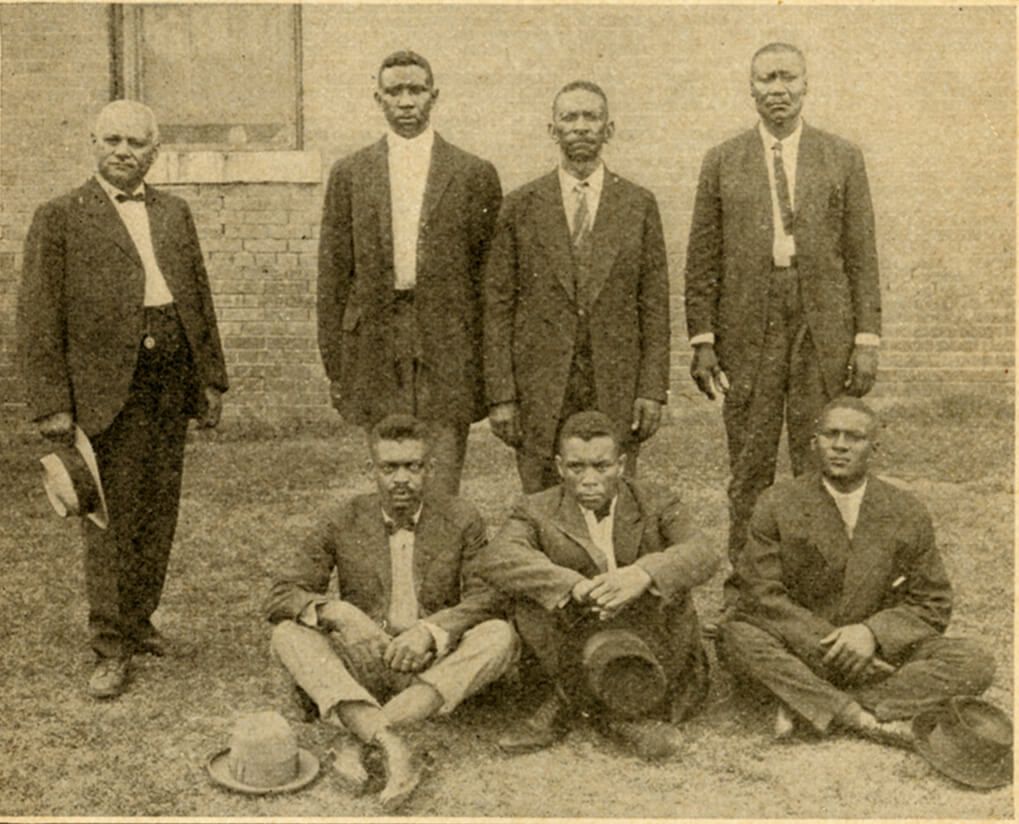

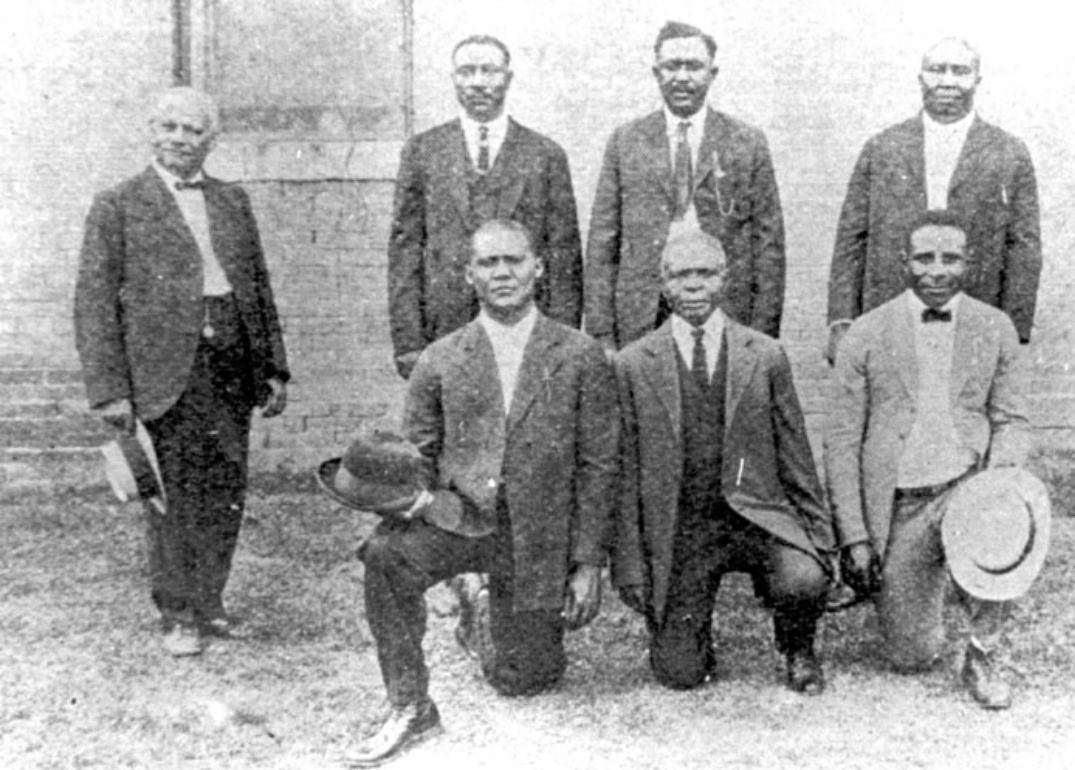

The most significant case in which Jones was involved, though, was the defense of twelve black men arrested during the Elaine Massacre. Between November 3 and 17, 1919, twelve men were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death for murder in their roles in a supposed black uprising; the trials were marked by weak evidence, a lack of cross-examination of witnesses, and short deliberations by the local juries. Jones was hired by African-American citizens of Little Rock on November 24, 1919, to work with the firm of George W. Murphy, an attorney hired by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), to defend the twelve condemned men. By January 14, 1925, all twelve defendants had been released. In one legal brief, Jones described his case as “the greatest case against peonage and mob law ever fought in the land.”

As a leader in the African-American community in Little Rock, Jones is also recognized as responsible for preventing a repeat of the Elaine Massacre in the state’s capital city. He and other community leaders persuaded their fellow African-American citizens to remain out of sight and avoid confrontation amidst the mob violence surrounding the lynching of John Carter on May 4, 1927.

Jones was, at times, criticized for his non-confrontational approach to race relations. He counted many leading white citizens of Arkansas among his friends, including Governor George Donaghey, and Jones—like John Bush of the Mosaic Templars of America (MTA)—worked with Booker T. Washington in building a black middle- and upper-class society separate from white society. However, when the leaders of the Republican Party in Arkansas sought to exclude African Americans from the workings of the party, Jones resisted. In 1900 and 1902, Jones worked to present a slate of delegates from Pulaski County to the state Republican Party convention, which included African Americans. In both cases, the slate was rejected by party leadership. Jones himself ran for the Little Rock school board in 1902 but was defeated by a vote of 2,202 to 181 after the Arkansas Gazette published warnings about the danger of having a black man seated on the school board.

In 1920, Jones helped to organize a separate party convention for black voters after the Pulaski County convention was moved without advance notice being given to African Americans, but both the state and national party conventions refused to seat the black delegates. In 1924, the Republican state committee did agree to hold party conventions in “places where all Republicans can attend” and expanded its committee to include two positions reserved for African Americans. On May 1, 1928, Jones was chosen as a delegate from Arkansas to the Republican National Convention. He also served in this position in 1940. In 1930, Jones was among a group of African-American lawyers who sued (unsuccessfully) the Democratic Party in Arkansas to reverse rules that prevented black citizens from voting in the Democratic state primary elections.

In addition to his legal and political careers, Jones attempted to gain income through investments, although he appears not to have been successful. Jones is said to have owned roughly ten houses in Little Rock around 1907, including a “splendid” house in which he and his family lived at 1808 Ringo Street. Jones was a major stockholder in the Arkansas Realty and Investment Company and was also elected president of the company. The corporation failed and was dissolved on June 19, 1911. Jones also heavily invested in the People’s Ice and Fuel Company of Little Rock, which succeeded for a time but failed during the Depression.

Jones was married twice. His first wife, Carrie Edwards Jones, was twenty-five when they were married on March 14, 1896. They had a daughter, Hazel, who died as a young adult. After the death of Carrie, Jones married Lillie M. Jackson of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) in 1917. The couple had no children.

Jones died in his home in Little Rock on March 28, 1943. His funeral at Bethel AME Church in Little Rock (where Jones had been a member for over fifty years) was attended by many government and political leaders, both black and white. He was buried at Haven of Rest Cemetery in Little Rock. Among the honors given to Jones are two significant buildings named for him. The junior and senior high school in North Little Rock was named for him from its construction in 1928 until its closing (due to the end of segregated education) in 1970. The U.S. post office at 1700 Main Street in Little Rock was named for Jones in 2007.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Scipio Africanus JonesScipio Africanus Jones was born in Dallas County, Arkansas, around August 1863-64. Jones was first admitted to practice in the circuit court of Pulaski County (Little Rock), Arkansas, on June 15, 1889, and to the state Supreme Court on November 26, 1900. Ultimately, Scipio Jones would be admitted to practice before the United States District Court in 1901, to the United States Supreme Court in 1905, and to the United States Court of Appeals in 1914.

After education both at Philander Smith College and Shorter College in Little Rock, Jones followed the traditional route of studying law under the mentorship of several lawyers (in his case, prominent white Little Rock lawyers), later passing a bar examination administered by three other members of the Little Rock bar.

After admission, Jones quickly developed a good business practice. He was active in the Wonder State Bar Association, a Black lawyers’ group, and in Booker T. Washington’s National Negro Business League (NNBL). He was instrumental in creating a “black lawyers’ auxiliary” in 1909. When the National Negro Bar Association held its organizational meeting in Little Rock, Jones was selected as its first treasurer. The initial goal of the group was to support Black businessmen, but organizing also provided a means of communication between Black lawyers across the country. In 1914, its goals expanded to include protecting the civil rights of all Black citizens. The NNBA soon separated from the Business League and, in 1926, was incorporated in its own right.

Jones, in addition to his business practice, also devoted time to cases involving racial and other discrimination. Beginning in 1901, in at least five cases, Jones presented the argument that criminal convictions of defendants should be overturned because the juries that indicted or convicted them included no African-Americans and the verdicts were therefore discriminatory and unconstitutional. In 1918, Jones made the same argument in a trial court motion to squash an indictment against a man for forging divorce decrees. This legal argument later would be used successfully by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in its work.

Jones is reported to have won a civil case against white Shriners who had sold fraternal regalia to African-American Shriners, then tried to prevent them from using it. In 1905, Scipio Jones was part of a successful fight against an unfair county convict labor leasing system. Jones also is reported to have sued a planter for mistreating convicts leased to him.

The case that made Scipio Jones a national legal figure, however, arose out of the “riots” of 1919 occurring near Elaine, Arkansas. Three days of fighting between whites and African-Americans between September 30 and October 4 resulted in the deaths of five white men and an untold number of Blacks (estimates range between 25 and several hundred). One hundred-forty-three African-American men were arrested by the authorities, and 73 were indicted by a grand jury. Twelve of them were convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death in hasty trials. George W. Murphy, a white attorney, and Scipio Jones represented the twelve, while Jones alone negotiated on behalf of about 60 others sentenced to prison terms.

Almost four years later, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that the circumstances existing at the time had not allowed the defendants a fair trial (Moore v. Dempsey), and sent the case back to Arkansas for a new trial. By 1925, all 12 of the condemned men and the others sentenced to prison terms were released.

In 1930, Jones and other African-American lawyers represented the Arkansas Negro Democratic Association (ANDA) in a suit against the Democratic Party to win the right to vote in Democratic primaries. Although they took the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, they lost. Just before his death in 1943, Jones joined with other African-American attorneys and the NAACP in an equal pay demand by a Little Rock African-American public school teacher. Although Jones died before the verdict, the suit was successful. Scipio Jones appears as attorney of record in forty-five published opinions.

Jones was the first African-American lawyer to create a record of appearances before the state Supreme Court. He appeared in that court and in the federal district court in 45 cases between 1891 and 1943. Jones was respected by white members of the bar, and twice, in 1915 and in 1924, was elected by them to preside over cases when the usual judge had a conflict. Once in circuit court and once in chancery court, Scipio Jones presided over matters involving Black parties and witnesses.

Jones was an active Republican all his life. In 1891, he worked against passage of the “Separate Coach” bill. In 1902, he, Archie V. Jones (no relation), and J. A. Robinson created the Independent Political League and offered their own slate of candidates for county offices in opposition to the regular political parties. In 1911, he headed the Negro State Suffrage League, which successfully opposed efforts to amend the state constitution to insert a “grandfather clause” and impose other educational requirements for voting. Thereafter, and into the 1920s, he worked with other Black lawyers in fighting for Black power and influence in candidate selection and issues within the Republican Party, holding their own state conventions in 1914 and 1916. When the Republicans held their 1920 state convention in a segregated hotel, Jones, J.A. Hibbler, J.R. Booker, W.A. Singfield, W.L. Purifoy, and others attended and refused to leave until the lights were turned off. They then held their own separate convention. Despite these differences with the party, Jones was the state’s most prominent Black Republican after Mifflin Gibbs’ death in 1915. Jones served as a delegate to the GOP’s National Conventions in 1912, 1928 and in 1940.

He also provided leadership for other lawyers. Scipio Jones had working and mentoring relationships with a number of African-American attorneys, both his peers and younger men. He shared a practice with John A. Robinson from 1893 through 1896. Later, between 1900 and 1903, he partnered with Archie V. Jones. City directories show attorney John W. Gaines in a partnership with Scipio Jones between 1906 and 1908. In 1908, Thomas J. Price began a fairly lengthy partnership with Jones. In 1912, John Gaines rejoined Scipio Jones and Thomas J. Price to create Jones, Price & Gaines. That relationship lasted until 1915, when Price left the office and Milton Wayman Guy arrived, changing the firm name to Jones, Gaines & Guy. This union lasted only one year. In 1916, Guy was on his own and in 1917, John Gaines returned to solo practice.

After 1917, Scipio Jones was not listed in a partnership, but only as a solo practitioner. However, he continued to work with a number of lawyers on an ad hoc basis. For example, Thomas Price, J.R. Booker and John Hibbler worked with Jones in the Elaine cases. Scipio Jones practiced in Pulaski County for a total of 54 years. He is listed as attorney of record in 27 civil cases between 1909 and 1944 and 18 criminal law cases between 1901 and 1943.

Scipio Jones also ventured into business and civic affairs in the larger community. He ran, unsuccessfully, for a place on the Little Rock School Board in 1903. He helped the city of Little Rock obtain a large loan by threatening to withdraw client funds from the banks. In 1908, he created the Arkansas Realty and Investment Company with attorney Thomas J. Price and others. This business was intended to help Blacks purchase homes. It failed after three years. He engineered the purchase by the Mosaic Templars (an Arkansas-created fraternal organization) of $125,000 in Liberty Bonds during World War I. Jones was an early member of the first Arkansas branch of the NAACP in Little Rock in 1926. He also served as director of the United Charities drive (a predecessor of the United Way).

In 1941, Scipio Jones pressured the University of Arkansas directly to provide tuition assistance for an African-American graduate student who could not obtain legal education in the state. He was successful, but only in part. The University paid his client’s tuition and the state legislature later appropriated money for the purpose, but the money was deducted from the budget of Arkansas Mechanical & Normal College, which provided the only state-supported higher education in Arkansas for Blacks at that time.

Scipio Jones was married about 1890 to Carrie, who was from Louisiana. They had a child Hazel, born about 1892. As of 1900, he owned his own home. Carrie died before 1910, when the census reports him living alone and widowed. Jones remarried, some time between 1910 and 1920, to Lillie, age 44, an Arkansas native. A servant is also shown as residing in the home in 1920. Scipio Jones died on March 2, 1943.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Prominent African-American attorney in Arkansas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Husband of Carrie E. Jones (buried at Fraternal Cemetery in Little Rock).

Scipio Jones was born to a slave, Jemmima Jones, in 1863 in the area of Tulip (Dallas County). His father is generally considered to be Dr. Sanford Reamey, a prominent citizen of Tulip and the owner of Jemmima at the time of Jones’s birth. Jones attended schools for African Americans in the Tulip area and later moved to Little Rock, attending Walden Seminary (now Philander Smith College), where he completed the four-year college preparatory course in only three years. He then attended Bethel Institute (now Shorter College) in North Little Rock (Pulaski County), from which he received a bachelor’s degree in 1885. During the next four years, Jones taught public school while studying law on his own time. On June 15, 1889, Jones passed the bar. His credentials were accepted by the Supreme Court of Arkansas in 1900 and by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1905.

Jones practiced law in Little Rock for the rest of his life. He frequently represented indigent citizens and worked to correct abuse and injustice in Arkansas’s penal system; Jones twice served in temporary capacity as a judge. He was elected a special judge to hear a case in the Little Rock Municipal Court when the regular judge disqualified himself. In 1924, Jones was elected a special chancellor in Pulaski County Chancery Court.

The most significant case in which Jones was involved, though, was the defense of twelve black men arrested during the Elaine Massacre. Between November 3 and 17, 1919, twelve men were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death for murder in their roles in a supposed black uprising; the trials were marked by weak evidence, a lack of cross-examination of witnesses, and short deliberations by the local juries. Jones was hired by African-American citizens of Little Rock on November 24, 1919, to work with the firm of George W. Murphy, an attorney hired by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), to defend the twelve condemned men. By January 14, 1925, all twelve defendants had been released. In one legal brief, Jones described his case as “the greatest case against peonage and mob law ever fought in the land.”

As a leader in the African-American community in Little Rock, Jones is also recognized as responsible for preventing a repeat of the Elaine Massacre in the state’s capital city. He and other community leaders persuaded their fellow African-American citizens to remain out of sight and avoid confrontation amidst the mob violence surrounding the lynching of John Carter on May 4, 1927.

Jones was, at times, criticized for his non-confrontational approach to race relations. He counted many leading white citizens of Arkansas among his friends, including Governor George Donaghey, and Jones—like John Bush of the Mosaic Templars of America (MTA)—worked with Booker T. Washington in building a black middle- and upper-class society separate from white society. However, when the leaders of the Republican Party in Arkansas sought to exclude African Americans from the workings of the party, Jones resisted. In 1900 and 1902, Jones worked to present a slate of delegates from Pulaski County to the state Republican Party convention, which included African Americans. In both cases, the slate was rejected by party leadership. Jones himself ran for the Little Rock school board in 1902 but was defeated by a vote of 2,202 to 181 after the Arkansas Gazette published warnings about the danger of having a black man seated on the school board.

In 1920, Jones helped to organize a separate party convention for black voters after the Pulaski County convention was moved without advance notice being given to African Americans, but both the state and national party conventions refused to seat the black delegates. In 1924, the Republican state committee did agree to hold party conventions in “places where all Republicans can attend” and expanded its committee to include two positions reserved for African Americans. On May 1, 1928, Jones was chosen as a delegate from Arkansas to the Republican National Convention. He also served in this position in 1940. In 1930, Jones was among a group of African-American lawyers who sued (unsuccessfully) the Democratic Party in Arkansas to reverse rules that prevented black citizens from voting in the Democratic state primary elections.

In addition to his legal and political careers, Jones attempted to gain income through investments, although he appears not to have been successful. Jones is said to have owned roughly ten houses in Little Rock around 1907, including a “splendid” house in which he and his family lived at 1808 Ringo Street. Jones was a major stockholder in the Arkansas Realty and Investment Company and was also elected president of the company. The corporation failed and was dissolved on June 19, 1911. Jones also heavily invested in the People’s Ice and Fuel Company of Little Rock, which succeeded for a time but failed during the Depression.

Jones was married twice. His first wife, Carrie Edwards Jones, was twenty-five when they were married on March 14, 1896. They had a daughter, Hazel, who died as a young adult. After the death of Carrie, Jones married Lillie M. Jackson of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) in 1917. The couple had no children.

Jones died in his home in Little Rock on March 28, 1943. His funeral at Bethel AME Church in Little Rock (where Jones had been a member for over fifty years) was attended by many government and political leaders, both black and white. He was buried at Haven of Rest Cemetery in Little Rock. Among the honors given to Jones are two significant buildings named for him. The junior and senior high school in North Little Rock was named for him from its construction in 1928 until its closing (due to the end of segregated education) in 1970. The U.S. post office at 1700 Main Street in Little Rock was named for Jones in 2007.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Scipio Africanus JonesScipio Africanus Jones was born in Dallas County, Arkansas, around August 1863-64. Jones was first admitted to practice in the circuit court of Pulaski County (Little Rock), Arkansas, on June 15, 1889, and to the state Supreme Court on November 26, 1900. Ultimately, Scipio Jones would be admitted to practice before the United States District Court in 1901, to the United States Supreme Court in 1905, and to the United States Court of Appeals in 1914.

After education both at Philander Smith College and Shorter College in Little Rock, Jones followed the traditional route of studying law under the mentorship of several lawyers (in his case, prominent white Little Rock lawyers), later passing a bar examination administered by three other members of the Little Rock bar.

After admission, Jones quickly developed a good business practice. He was active in the Wonder State Bar Association, a Black lawyers’ group, and in Booker T. Washington’s National Negro Business League (NNBL). He was instrumental in creating a “black lawyers’ auxiliary” in 1909. When the National Negro Bar Association held its organizational meeting in Little Rock, Jones was selected as its first treasurer. The initial goal of the group was to support Black businessmen, but organizing also provided a means of communication between Black lawyers across the country. In 1914, its goals expanded to include protecting the civil rights of all Black citizens. The NNBA soon separated from the Business League and, in 1926, was incorporated in its own right.

Jones, in addition to his business practice, also devoted time to cases involving racial and other discrimination. Beginning in 1901, in at least five cases, Jones presented the argument that criminal convictions of defendants should be overturned because the juries that indicted or convicted them included no African-Americans and the verdicts were therefore discriminatory and unconstitutional. In 1918, Jones made the same argument in a trial court motion to squash an indictment against a man for forging divorce decrees. This legal argument later would be used successfully by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in its work.

Jones is reported to have won a civil case against white Shriners who had sold fraternal regalia to African-American Shriners, then tried to prevent them from using it. In 1905, Scipio Jones was part of a successful fight against an unfair county convict labor leasing system. Jones also is reported to have sued a planter for mistreating convicts leased to him.

The case that made Scipio Jones a national legal figure, however, arose out of the “riots” of 1919 occurring near Elaine, Arkansas. Three days of fighting between whites and African-Americans between September 30 and October 4 resulted in the deaths of five white men and an untold number of Blacks (estimates range between 25 and several hundred). One hundred-forty-three African-American men were arrested by the authorities, and 73 were indicted by a grand jury. Twelve of them were convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death in hasty trials. George W. Murphy, a white attorney, and Scipio Jones represented the twelve, while Jones alone negotiated on behalf of about 60 others sentenced to prison terms.

Almost four years later, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that the circumstances existing at the time had not allowed the defendants a fair trial (Moore v. Dempsey), and sent the case back to Arkansas for a new trial. By 1925, all 12 of the condemned men and the others sentenced to prison terms were released.

In 1930, Jones and other African-American lawyers represented the Arkansas Negro Democratic Association (ANDA) in a suit against the Democratic Party to win the right to vote in Democratic primaries. Although they took the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, they lost. Just before his death in 1943, Jones joined with other African-American attorneys and the NAACP in an equal pay demand by a Little Rock African-American public school teacher. Although Jones died before the verdict, the suit was successful. Scipio Jones appears as attorney of record in forty-five published opinions.

Jones was the first African-American lawyer to create a record of appearances before the state Supreme Court. He appeared in that court and in the federal district court in 45 cases between 1891 and 1943. Jones was respected by white members of the bar, and twice, in 1915 and in 1924, was elected by them to preside over cases when the usual judge had a conflict. Once in circuit court and once in chancery court, Scipio Jones presided over matters involving Black parties and witnesses.

Jones was an active Republican all his life. In 1891, he worked against passage of the “Separate Coach” bill. In 1902, he, Archie V. Jones (no relation), and J. A. Robinson created the Independent Political League and offered their own slate of candidates for county offices in opposition to the regular political parties. In 1911, he headed the Negro State Suffrage League, which successfully opposed efforts to amend the state constitution to insert a “grandfather clause” and impose other educational requirements for voting. Thereafter, and into the 1920s, he worked with other Black lawyers in fighting for Black power and influence in candidate selection and issues within the Republican Party, holding their own state conventions in 1914 and 1916. When the Republicans held their 1920 state convention in a segregated hotel, Jones, J.A. Hibbler, J.R. Booker, W.A. Singfield, W.L. Purifoy, and others attended and refused to leave until the lights were turned off. They then held their own separate convention. Despite these differences with the party, Jones was the state’s most prominent Black Republican after Mifflin Gibbs’ death in 1915. Jones served as a delegate to the GOP’s National Conventions in 1912, 1928 and in 1940.

He also provided leadership for other lawyers. Scipio Jones had working and mentoring relationships with a number of African-American attorneys, both his peers and younger men. He shared a practice with John A. Robinson from 1893 through 1896. Later, between 1900 and 1903, he partnered with Archie V. Jones. City directories show attorney John W. Gaines in a partnership with Scipio Jones between 1906 and 1908. In 1908, Thomas J. Price began a fairly lengthy partnership with Jones. In 1912, John Gaines rejoined Scipio Jones and Thomas J. Price to create Jones, Price & Gaines. That relationship lasted until 1915, when Price left the office and Milton Wayman Guy arrived, changing the firm name to Jones, Gaines & Guy. This union lasted only one year. In 1916, Guy was on his own and in 1917, John Gaines returned to solo practice.

After 1917, Scipio Jones was not listed in a partnership, but only as a solo practitioner. However, he continued to work with a number of lawyers on an ad hoc basis. For example, Thomas Price, J.R. Booker and John Hibbler worked with Jones in the Elaine cases. Scipio Jones practiced in Pulaski County for a total of 54 years. He is listed as attorney of record in 27 civil cases between 1909 and 1944 and 18 criminal law cases between 1901 and 1943.

Scipio Jones also ventured into business and civic affairs in the larger community. He ran, unsuccessfully, for a place on the Little Rock School Board in 1903. He helped the city of Little Rock obtain a large loan by threatening to withdraw client funds from the banks. In 1908, he created the Arkansas Realty and Investment Company with attorney Thomas J. Price and others. This business was intended to help Blacks purchase homes. It failed after three years. He engineered the purchase by the Mosaic Templars (an Arkansas-created fraternal organization) of $125,000 in Liberty Bonds during World War I. Jones was an early member of the first Arkansas branch of the NAACP in Little Rock in 1926. He also served as director of the United Charities drive (a predecessor of the United Way).

In 1941, Scipio Jones pressured the University of Arkansas directly to provide tuition assistance for an African-American graduate student who could not obtain legal education in the state. He was successful, but only in part. The University paid his client’s tuition and the state legislature later appropriated money for the purpose, but the money was deducted from the budget of Arkansas Mechanical & Normal College, which provided the only state-supported higher education in Arkansas for Blacks at that time.

Scipio Jones was married about 1890 to Carrie, who was from Louisiana. They had a child Hazel, born about 1892. As of 1900, he owned his own home. Carrie died before 1910, when the census reports him living alone and widowed. Jones remarried, some time between 1910 and 1920, to Lillie, age 44, an Arkansas native. A servant is also shown as residing in the home in 1920. Scipio Jones died on March 2, 1943.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Prominent African-American attorney in Arkansas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Husband of Carrie E. Jones (buried at Fraternal Cemetery in Little Rock).

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement