Fort Collins Coloradoan, June 20, 2015 by Erin Udell

He sounded like the hero in an old Western.

Six feet tall, straight and lithe, the Fort Collins Express described Joseph Mason as a man with a tawny complexion, clear, large eyes and hair as "black as jet."

Mason wasn't his real name, and English wasn't his first language, but the black-bearded French Canadian found his footing in Fort Collins. He settled here in 1862 at the age of 22.

That next winter, after six feet of snow and torrential rain in the Cache la Poudre Valley, he's said to have convinced Lt. James Hanna to move the flooded Army post Camp Collins from Laporte to where Fort Collins is today.

There, Mason was known as the first white settler. He built its first store, became its first sheriff and served as its first postmaster.

In 1870, Mason married Luella Blake in the second wedding performed in the town's history. The couple had four children, but Mason had another fledgling all his own. The city was his baby and, with an eye for opportunity, he was going to put it on the map.

Sitting at his home in Silver Spring, Maryland, the great-grandnephew of Joseph Mason rattles off the remaining Masons over the phone. There are his three older brothers — all still alive — and their sons. Then there's his son and grandsons.

"In Maryland, it's not a big piece of history," Charles N. Mason Jr. said of his family.

But out West, it's a different story.

"Joseph Mason is a big piece of Fort Collins," he said. "He's sort of a footnote of Colorado history."

Charles, 84, is the great-grandson of Augustin Mason, one of Joseph's older brothers.

After finding some family papers and getting them translated from French, Charles started hunting down more information, becoming a sort of Mason family historian.

Starting in the 1970s, whenever he flew into Denver for business trips during his time at the Department of Labor, Charles said he would take a few days off and drive up to Fort Collins, where his great-grandfather ventured in 1866 at the urging of his baby brother, Joseph.

There, Charles would go through documents and visit with Col. Joe Mason, Joseph Mason's grandson, who died in Fort Collins in the 1970s. He had no children.

Charles' research has been primarily focused around Joseph Mason's brother and that family line — he wrote a small book about Augustin in the 1990s — but he has collected information on Joseph.

Retired for more than 20 years, Charles has piles of research he's starting to finally write up. The stack of papers on Joseph Mason is about six to eight inches thick and he's only written up to about 1863, when Joseph was just finding himself out West — back before the black bottle, the duel over Mary Polzell, the escape of Happy Jack and the hoof to the head that killed him.

Born as Joseph Messier, Mason was the baby of a 10-person family of farmers near Montreal.

He immigrated to the United States, where he lived in New England as a teenager and Americanized his name. By 19, he had joined an expedition to explore the headwaters of the Yellowstone River. That winter, in February 1860, he left the party and arrived in Laporte, where he found a small settlement of trappers and mountaineers, according to an article in the Fort Collins Review.

After spending some time in the state's mining camps, Mason returned to the Cache la Poudre Valley.

By that time — 1862 — he was 22 and on the lookout for land. He purchased a farm just northwest of Fort Collins from a Native American widow. And when flooding threatened to destroy Camp Collins, Mason successfully made the case to make Fort Collins its new home.

Some accounts say his argument was made stronger by the "contents of a black bottle" in his pocket.

Mason, no doubt, had some selfish reasons for recommending the site. It was just a mile downstream from his land. And, according to a newspaper article written by Bruce Roldo, he would gain a market for hay and protection from the camp's soldiers.

But it also made sense. The site was close to the river, but situated on high, dry land with good drainage and a better view of the county.

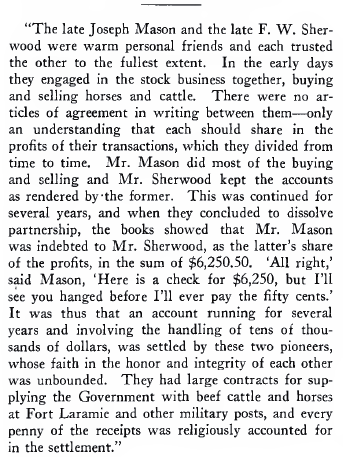

Mason was named one of the sutlers of the fort, giving him the power to erect buildings near the camp and sell goods to soldiers. He built a little concrete store where he offered a small glass of beer for 25 cents and a pint of whiskey for $3, according to the Review. He later ran the Lindell mill and sold horses and beef to Fort Laramie and other military posts.

In 1871, he was elected the first sheriff in Fort Collins and even had a brush with noted Northern Colorado criminal Happy Jack — Mason arrested him, only to have Happy Jack escape his custody.

And, in true Wild West fashion, he was also dragged into a duel with a blacksmith over a Native American maiden named Mary Polzell. Mason accepted the blacksmith's challenge and met him on the banks of the Platte River.

"It was a fizzle," according to an account in Ansel Watrous' "History of Larimer County, Colorado."

"The blacksmith's teeth began to chatter as the umpire paced the ground, and when the seconds loaded the pistols his knees gave way," Watrous wrote. "He fell to the ground a limp and limpsy lover."

Mason later found love closer to home with Luella Blake, whose father owned a hotel on the Overland Trail near Longmont. He married her — 10 years his junior — in 1870.

After 11 years of marriage, four children and almost two decades in Fort Collins, Mason met his untimely end at 41. Some accounts say he was leaving a sick friend's house when his horse refused to cross Dry Creek stream. Others say he was at his friend F.W. Sherwood's farm, breaking a horse to harness.

Either way, on Feb. 17, 1881, he took a hoof to the head, leaving doctors to pull 62 shards of skull from a fracture nearly the shape of a horseshoe behind his right eyebrow, according to the Fort Collins Courier. Telegrams were sent, summoning the best doctors and surgeons from Denver and Cheyenne. And he even rallied the next day, waking up and talking about his business affairs.

But, after an operation, Mason never woke up. He died at 1 p.m. in his home at the corner of Pine and Jefferson streets.

"A feeling of unutterable sadness pervaded every heart, and there was mourning in every home," according to the Fort Collins Courier, which called Mason's funeral the largest and most imposing the city had ever seen.

Friends came from miles away to honor an honorable man and, according to the Courier, recognize the one thing was clear ever since Mason came to stay in the Cache la Poudre Valley.

"From that day until the day of his death, amid all the trials and discouragements incident to pioneer life, he never lost faith in the future of Fort Collins."

Fort Collins Coloradoan, June 20, 2015 by Erin Udell

He sounded like the hero in an old Western.

Six feet tall, straight and lithe, the Fort Collins Express described Joseph Mason as a man with a tawny complexion, clear, large eyes and hair as "black as jet."

Mason wasn't his real name, and English wasn't his first language, but the black-bearded French Canadian found his footing in Fort Collins. He settled here in 1862 at the age of 22.

That next winter, after six feet of snow and torrential rain in the Cache la Poudre Valley, he's said to have convinced Lt. James Hanna to move the flooded Army post Camp Collins from Laporte to where Fort Collins is today.

There, Mason was known as the first white settler. He built its first store, became its first sheriff and served as its first postmaster.

In 1870, Mason married Luella Blake in the second wedding performed in the town's history. The couple had four children, but Mason had another fledgling all his own. The city was his baby and, with an eye for opportunity, he was going to put it on the map.

Sitting at his home in Silver Spring, Maryland, the great-grandnephew of Joseph Mason rattles off the remaining Masons over the phone. There are his three older brothers — all still alive — and their sons. Then there's his son and grandsons.

"In Maryland, it's not a big piece of history," Charles N. Mason Jr. said of his family.

But out West, it's a different story.

"Joseph Mason is a big piece of Fort Collins," he said. "He's sort of a footnote of Colorado history."

Charles, 84, is the great-grandson of Augustin Mason, one of Joseph's older brothers.

After finding some family papers and getting them translated from French, Charles started hunting down more information, becoming a sort of Mason family historian.

Starting in the 1970s, whenever he flew into Denver for business trips during his time at the Department of Labor, Charles said he would take a few days off and drive up to Fort Collins, where his great-grandfather ventured in 1866 at the urging of his baby brother, Joseph.

There, Charles would go through documents and visit with Col. Joe Mason, Joseph Mason's grandson, who died in Fort Collins in the 1970s. He had no children.

Charles' research has been primarily focused around Joseph Mason's brother and that family line — he wrote a small book about Augustin in the 1990s — but he has collected information on Joseph.

Retired for more than 20 years, Charles has piles of research he's starting to finally write up. The stack of papers on Joseph Mason is about six to eight inches thick and he's only written up to about 1863, when Joseph was just finding himself out West — back before the black bottle, the duel over Mary Polzell, the escape of Happy Jack and the hoof to the head that killed him.

Born as Joseph Messier, Mason was the baby of a 10-person family of farmers near Montreal.

He immigrated to the United States, where he lived in New England as a teenager and Americanized his name. By 19, he had joined an expedition to explore the headwaters of the Yellowstone River. That winter, in February 1860, he left the party and arrived in Laporte, where he found a small settlement of trappers and mountaineers, according to an article in the Fort Collins Review.

After spending some time in the state's mining camps, Mason returned to the Cache la Poudre Valley.

By that time — 1862 — he was 22 and on the lookout for land. He purchased a farm just northwest of Fort Collins from a Native American widow. And when flooding threatened to destroy Camp Collins, Mason successfully made the case to make Fort Collins its new home.

Some accounts say his argument was made stronger by the "contents of a black bottle" in his pocket.

Mason, no doubt, had some selfish reasons for recommending the site. It was just a mile downstream from his land. And, according to a newspaper article written by Bruce Roldo, he would gain a market for hay and protection from the camp's soldiers.

But it also made sense. The site was close to the river, but situated on high, dry land with good drainage and a better view of the county.

Mason was named one of the sutlers of the fort, giving him the power to erect buildings near the camp and sell goods to soldiers. He built a little concrete store where he offered a small glass of beer for 25 cents and a pint of whiskey for $3, according to the Review. He later ran the Lindell mill and sold horses and beef to Fort Laramie and other military posts.

In 1871, he was elected the first sheriff in Fort Collins and even had a brush with noted Northern Colorado criminal Happy Jack — Mason arrested him, only to have Happy Jack escape his custody.

And, in true Wild West fashion, he was also dragged into a duel with a blacksmith over a Native American maiden named Mary Polzell. Mason accepted the blacksmith's challenge and met him on the banks of the Platte River.

"It was a fizzle," according to an account in Ansel Watrous' "History of Larimer County, Colorado."

"The blacksmith's teeth began to chatter as the umpire paced the ground, and when the seconds loaded the pistols his knees gave way," Watrous wrote. "He fell to the ground a limp and limpsy lover."

Mason later found love closer to home with Luella Blake, whose father owned a hotel on the Overland Trail near Longmont. He married her — 10 years his junior — in 1870.

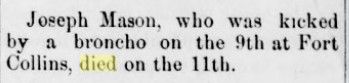

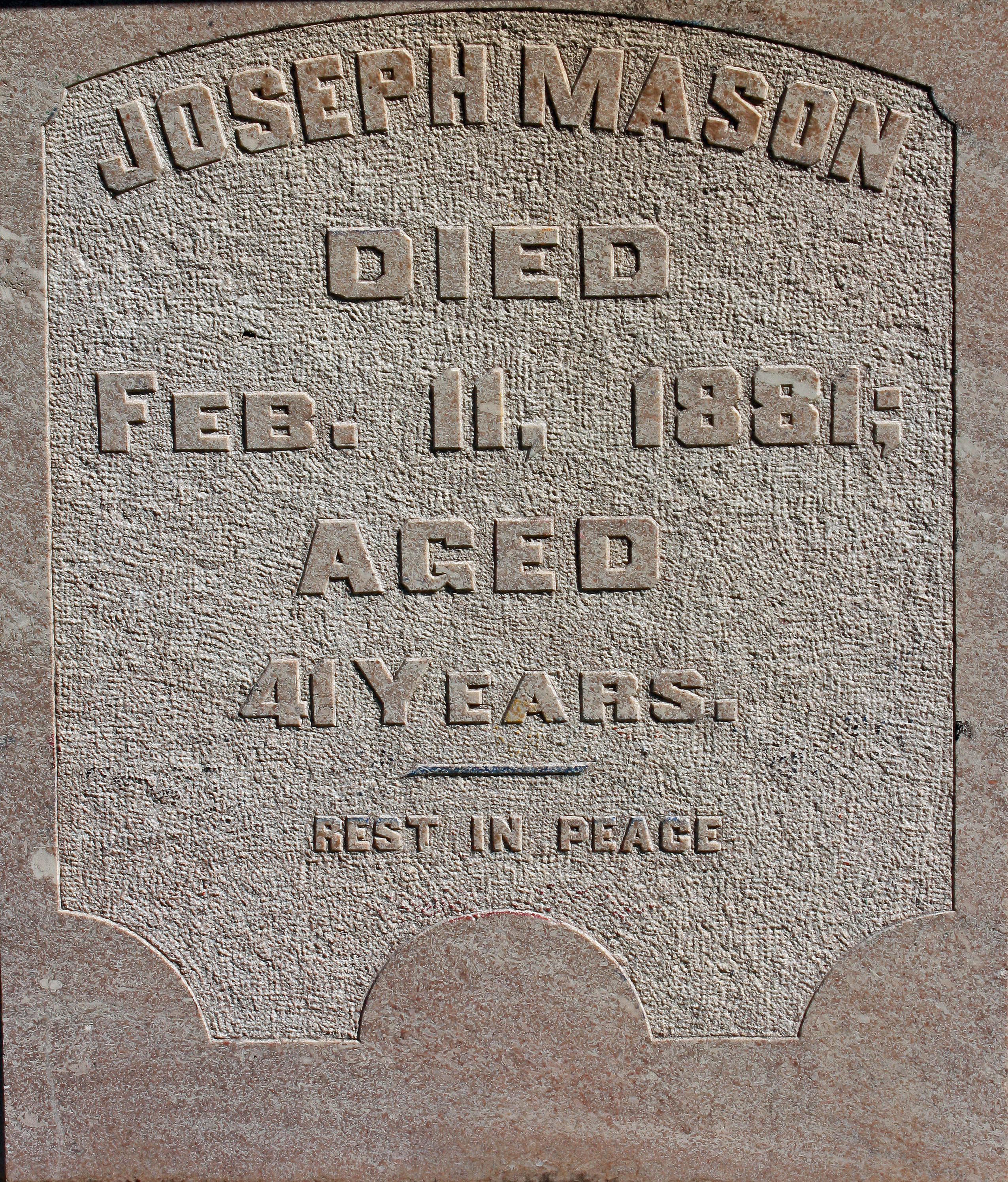

After 11 years of marriage, four children and almost two decades in Fort Collins, Mason met his untimely end at 41. Some accounts say he was leaving a sick friend's house when his horse refused to cross Dry Creek stream. Others say he was at his friend F.W. Sherwood's farm, breaking a horse to harness.

Either way, on Feb. 17, 1881, he took a hoof to the head, leaving doctors to pull 62 shards of skull from a fracture nearly the shape of a horseshoe behind his right eyebrow, according to the Fort Collins Courier. Telegrams were sent, summoning the best doctors and surgeons from Denver and Cheyenne. And he even rallied the next day, waking up and talking about his business affairs.

But, after an operation, Mason never woke up. He died at 1 p.m. in his home at the corner of Pine and Jefferson streets.

"A feeling of unutterable sadness pervaded every heart, and there was mourning in every home," according to the Fort Collins Courier, which called Mason's funeral the largest and most imposing the city had ever seen.

Friends came from miles away to honor an honorable man and, according to the Courier, recognize the one thing was clear ever since Mason came to stay in the Cache la Poudre Valley.

"From that day until the day of his death, amid all the trials and discouragements incident to pioneer life, he never lost faith in the future of Fort Collins."

Gravesite Details

One of the first pioneer settlers of Larmier County, Colorado and Fort Collins. Farmer and merchant. Donated some of land for the land grant college that is now Colorado State University. Died from being kicked by a horse.