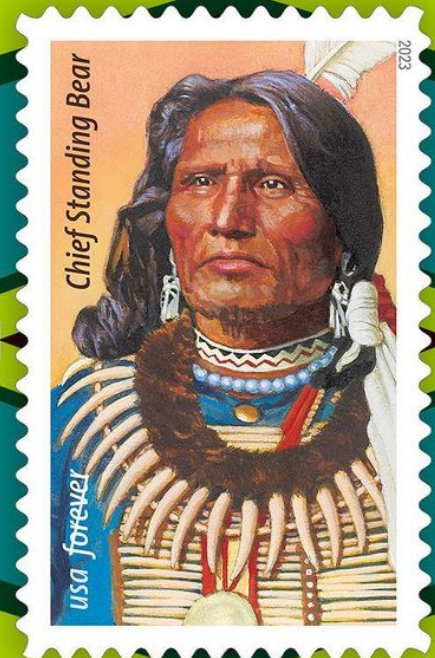

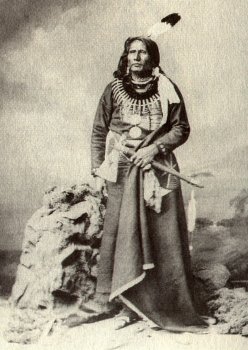

The Ponca lived with the Omaha, the Qapaw (Akana), and the Kaw (Kawnana) along the Atlantic coast in Virginia and the Carolinas. Sometime in the 1500s they migrated to the territory we now call Minnesota. Due to their conflicts with the Sioux we find that by the time of the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1803 they had settled along the Nebraska- South Dakota boarder near the Missouri and the swift running water (Niobrara) rivers. Their tribes were confused with the Sioux and although they tried to convince the Army they were not Souix they were ordered to Oklahoma after Little Big Horn. Chief Standing Bear was arrested for leaving the Oklahoma territories several times.

Standing Bear took the US government to court because he felt he could not live on the reservation lands allotted to the Poncas in Oklahoma. The fact that someone was suing the government was news and the fact that a chief from an unknown small Indian tribe was doing this made it big news. He argued successfully in U.S. District Court in 1879 that Native Americans are "persons within the meaning of the law" and have the right of habeas corpus. His wife Susette Primeau was also a signatory on the 1879 writ that initiated the famous court case.

The Ponca had arrived too late to plant crops, and were not provided farming equipment promised by the government. In 1878 they moved 150 miles west to the Salt Fork of the Arkansas River, south of present-day Ponca City, Oklahoma, and by spring nearly a third of the tribe had perished to starvation, malaria and related causes. Standing Bear's eldest son, Bear Shield, was among the dead, and Standing Bear had promised to bury him in the Niobrara River valley, so he left with 65 followers. They reached the Omaha Reservation, where they were welcomed as relatives, but word of their arrival in Nebraska soon reached the government. They were arrested by orders of Brigadier General George Crook, of the U.S. Army, himself under orders from the Secretary of the Interior, Carl Schurz. Standing Bear and the others were taken to Fort Omaha and detained. Although they were ordered back to Indian Territory at once, Crook, appalled by the conditions under which the Poncas were held, delayed their return so they could rest, regain their health, and seek legal redress

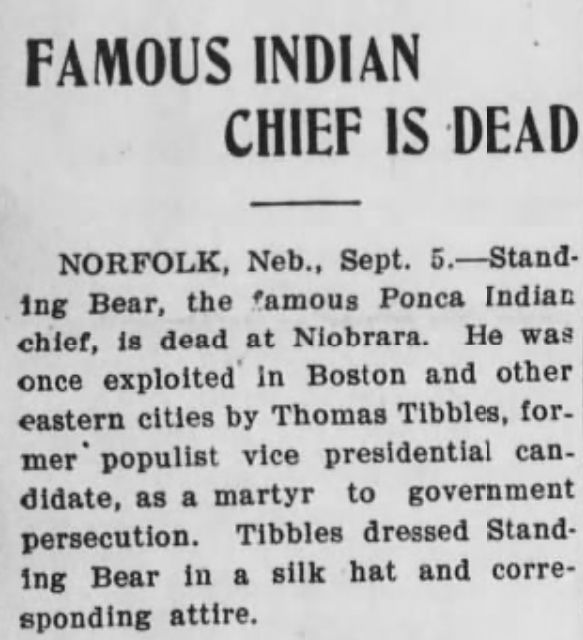

Crook told their story to Thomas Tibbles of the Omaha Daily Herald, who publicized it widely. Attorney John L. Webster offered his services pro bono, and he was joined by Andrew J. Poppleton, chief attorney of the Union Pacific Railroad, who also volunteered his services. In April 1879, Standing Bear sued for a writ of habeas corpus in U.S. District Court in Omaha, Nebraska. The case is called United States ex rel. Standing Bear v. Crook. General Crook was named as the formal defendant because he was holding the Poncas under color of law.

On May 12, 1879, Judge Elmer S. Dundy ruled that: "an Indian is a person" within the meaning of the habeas corpus act, and that the government had failed to show a basis under law for the Poncas' captivity. They were therefore freed immediately. This case received the attention of the Hayes administration, and provisions were made for some of the tribe to return to the Niobrara Valley.

In 1990 President George H. W. Bush signed the Ponca Restoration Act, which also conceded land owned by the Episcopalian Church back to the reservation.

The Ponca lived with the Omaha, the Qapaw (Akana), and the Kaw (Kawnana) along the Atlantic coast in Virginia and the Carolinas. Sometime in the 1500s they migrated to the territory we now call Minnesota. Due to their conflicts with the Sioux we find that by the time of the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1803 they had settled along the Nebraska- South Dakota boarder near the Missouri and the swift running water (Niobrara) rivers. Their tribes were confused with the Sioux and although they tried to convince the Army they were not Souix they were ordered to Oklahoma after Little Big Horn. Chief Standing Bear was arrested for leaving the Oklahoma territories several times.

Standing Bear took the US government to court because he felt he could not live on the reservation lands allotted to the Poncas in Oklahoma. The fact that someone was suing the government was news and the fact that a chief from an unknown small Indian tribe was doing this made it big news. He argued successfully in U.S. District Court in 1879 that Native Americans are "persons within the meaning of the law" and have the right of habeas corpus. His wife Susette Primeau was also a signatory on the 1879 writ that initiated the famous court case.

The Ponca had arrived too late to plant crops, and were not provided farming equipment promised by the government. In 1878 they moved 150 miles west to the Salt Fork of the Arkansas River, south of present-day Ponca City, Oklahoma, and by spring nearly a third of the tribe had perished to starvation, malaria and related causes. Standing Bear's eldest son, Bear Shield, was among the dead, and Standing Bear had promised to bury him in the Niobrara River valley, so he left with 65 followers. They reached the Omaha Reservation, where they were welcomed as relatives, but word of their arrival in Nebraska soon reached the government. They were arrested by orders of Brigadier General George Crook, of the U.S. Army, himself under orders from the Secretary of the Interior, Carl Schurz. Standing Bear and the others were taken to Fort Omaha and detained. Although they were ordered back to Indian Territory at once, Crook, appalled by the conditions under which the Poncas were held, delayed their return so they could rest, regain their health, and seek legal redress

Crook told their story to Thomas Tibbles of the Omaha Daily Herald, who publicized it widely. Attorney John L. Webster offered his services pro bono, and he was joined by Andrew J. Poppleton, chief attorney of the Union Pacific Railroad, who also volunteered his services. In April 1879, Standing Bear sued for a writ of habeas corpus in U.S. District Court in Omaha, Nebraska. The case is called United States ex rel. Standing Bear v. Crook. General Crook was named as the formal defendant because he was holding the Poncas under color of law.

On May 12, 1879, Judge Elmer S. Dundy ruled that: "an Indian is a person" within the meaning of the habeas corpus act, and that the government had failed to show a basis under law for the Poncas' captivity. They were therefore freed immediately. This case received the attention of the Hayes administration, and provisions were made for some of the tribe to return to the Niobrara Valley.

In 1990 President George H. W. Bush signed the Ponca Restoration Act, which also conceded land owned by the Episcopalian Church back to the reservation.

Inscription

Age 70 years.

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement