Born in Montreal, Quebec, to Napoléon and Marie Bourassa, Henri Bourassa was a grandson of the pro-democracy reformist politician Louis-Joseph Papineau. He was educated at Montreal's École polytechnique and at Holy Cross College in Worcester, Massachusetts. In 1890, he became mayor of the town of Montebello, Quebec, at age 22.

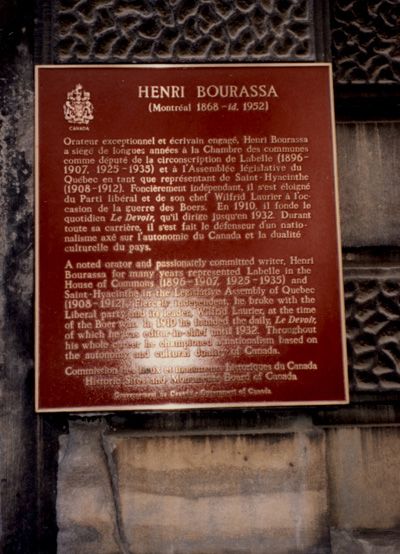

In 1896, he was elected to the House of Commons as an independent Liberal for Labelle County, but resigned in 1899 to protest against the sending of Canadian troops to the Second Boer War. He was re-elected soon after his resignation. He argued that Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier was un vendu ("a sell-out") to British imperialism and its supporters in Canada.

To counter what he perceived to be the evils of imperialism, in 1903 he created the Nationalist League (Ligue Nationaliste) to instill a pan-Canadian nationalist spirit in the Francophone population. The League opposed political dependence on either Britain or the United States, supporting instead Canadian autonomy within the British Empire.

Bourassa left the federal parliament in 1907, but remained active in Quebec politics. He continued to criticize Laurier, opposing Laurier's attempts to build a Canadian navy in 1911, which he believed would draw Canada into future imperial wars between Britain and Germany. He supported the eventual creation of an independent navy, but did not want it to be under British command, as Laurier had planned. Bourassa's attacks depleted Laurier's strength in Quebec, contributing to the Liberal Party's loss in the 1911 election. Ironically, Bourassa's moves aided in the election of the Conservatives, who held more staunchly Imperialist policies than the Liberals.

In 1910, he founded the newspaper Le Devoir to promote the Nationalist League, and served as its editor until 1932.

In 1913, Bourassa denounced the government of Ontario as "more Prussian than Prussia" during the Ontario Schools Question crisis (see Regulation 17), after Ontario almost banned the use of French in their schools and made English the official language of instruction. He charged his compatriots to see their enemies inside Canada, in 1915:

The enemies of the French language, of French civilization in Canada, are not the Boches on the shores of the Spree; but the English-Canadian anglicizers, the Orange intriguers, or Irish priests. Above all they are French Canadians weakened and degraded by the conquest and three centuries of colonial servitude. Let no mistake be made: if we let the Ontario minority be crushed, it will soon be the turn of other French groups in English Canada." [in Wade v 2 p 671]

Bourassa led French Canadian opposition to the participation in World War I, especially Robert Borden's plans to implement conscription in 1917. He agreed that the war was necessary for the survival of France and Britain, but felt that only those Canadians who volunteered for service should be sent to the battlefields of Europe. His opposition to conscription brought him the anglophone public's disfavour, as expressed by hostile crowd amassed in Ottawa that threw vegetables and eggs during his oration.[1]

Three months after stating that he had nothing more to do with politics, he returned to the House of Commons in the 1925 election with his election as an Independent MP, and remained until his defeat in the 1935 election. In the 1930s, Bourassa demanded that Canada keep its gates shut to Jewish immigrants, as did many other Canadian politicians of the time.

Bourassa also opposed the Conscription crisis of 1944 in World War II, though less effectively, and was a member of the Bloc populaire. His influence on Quebec's politics can still be seen today in all major provincial parties.

According to Michael C. Macmillan, Bourassa's political thought was largely a combination of Whig liberalism, Catholic social thought, and traditional Quebec political thought. He was distinctly liberal in his anti-imperialism and general support for civil liberties for French Canadians, while his approach to economic questions was essentially Catholic. While Bourassa embraced the ultramontane idea that the Church was responsible for faith, morals, discipline, and administration, he resisted Church involvement in the political sphere and rejected the corporatism espoused by the Church. Bourassa opposed state intervention wherever possible and increasingly throughout his career emphasized the need for moral reform.[2]

As Levitt has shown, attitudes of historians, both Anglophone and Francophone, toward Bourassa consistently have been colored by the position of each historian on the major issues Bourassa addressed. Goldwin Smith, a fellow anti-imperialist, introduced him into historical literature in 1902. The isolationism of the 1930s and the biculturalism of the 1960s (Bourassa, while a champion of Francophone rights, always opposed separatism) occasioned favourable treatment among Anglophones, while Lionel Groulx, his onetime foe, described him as "l'incomparable Éveilleur." Bourassa's position on social issues - Catholic, moderately reformist, emphasizing the family and agricultural values - likewise has called forth praise and blame.[3]

Upon his death in Outremont, Quebec in 1952, Henri Bourassa was interred in Montreal's Cimetière Notre-Dame-des-Neiges.

Henri Bourassa Blvd., Henri-Bourassa metro station, and the federal riding of Bourassa, all in Montreal, are named for him. He is not related to Robert Bourassa, the former premier of Quebec.

Member contributor #47133515

Born in Montreal, Quebec, to Napoléon and Marie Bourassa, Henri Bourassa was a grandson of the pro-democracy reformist politician Louis-Joseph Papineau. He was educated at Montreal's École polytechnique and at Holy Cross College in Worcester, Massachusetts. In 1890, he became mayor of the town of Montebello, Quebec, at age 22.

In 1896, he was elected to the House of Commons as an independent Liberal for Labelle County, but resigned in 1899 to protest against the sending of Canadian troops to the Second Boer War. He was re-elected soon after his resignation. He argued that Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier was un vendu ("a sell-out") to British imperialism and its supporters in Canada.

To counter what he perceived to be the evils of imperialism, in 1903 he created the Nationalist League (Ligue Nationaliste) to instill a pan-Canadian nationalist spirit in the Francophone population. The League opposed political dependence on either Britain or the United States, supporting instead Canadian autonomy within the British Empire.

Bourassa left the federal parliament in 1907, but remained active in Quebec politics. He continued to criticize Laurier, opposing Laurier's attempts to build a Canadian navy in 1911, which he believed would draw Canada into future imperial wars between Britain and Germany. He supported the eventual creation of an independent navy, but did not want it to be under British command, as Laurier had planned. Bourassa's attacks depleted Laurier's strength in Quebec, contributing to the Liberal Party's loss in the 1911 election. Ironically, Bourassa's moves aided in the election of the Conservatives, who held more staunchly Imperialist policies than the Liberals.

In 1910, he founded the newspaper Le Devoir to promote the Nationalist League, and served as its editor until 1932.

In 1913, Bourassa denounced the government of Ontario as "more Prussian than Prussia" during the Ontario Schools Question crisis (see Regulation 17), after Ontario almost banned the use of French in their schools and made English the official language of instruction. He charged his compatriots to see their enemies inside Canada, in 1915:

The enemies of the French language, of French civilization in Canada, are not the Boches on the shores of the Spree; but the English-Canadian anglicizers, the Orange intriguers, or Irish priests. Above all they are French Canadians weakened and degraded by the conquest and three centuries of colonial servitude. Let no mistake be made: if we let the Ontario minority be crushed, it will soon be the turn of other French groups in English Canada." [in Wade v 2 p 671]

Bourassa led French Canadian opposition to the participation in World War I, especially Robert Borden's plans to implement conscription in 1917. He agreed that the war was necessary for the survival of France and Britain, but felt that only those Canadians who volunteered for service should be sent to the battlefields of Europe. His opposition to conscription brought him the anglophone public's disfavour, as expressed by hostile crowd amassed in Ottawa that threw vegetables and eggs during his oration.[1]

Three months after stating that he had nothing more to do with politics, he returned to the House of Commons in the 1925 election with his election as an Independent MP, and remained until his defeat in the 1935 election. In the 1930s, Bourassa demanded that Canada keep its gates shut to Jewish immigrants, as did many other Canadian politicians of the time.

Bourassa also opposed the Conscription crisis of 1944 in World War II, though less effectively, and was a member of the Bloc populaire. His influence on Quebec's politics can still be seen today in all major provincial parties.

According to Michael C. Macmillan, Bourassa's political thought was largely a combination of Whig liberalism, Catholic social thought, and traditional Quebec political thought. He was distinctly liberal in his anti-imperialism and general support for civil liberties for French Canadians, while his approach to economic questions was essentially Catholic. While Bourassa embraced the ultramontane idea that the Church was responsible for faith, morals, discipline, and administration, he resisted Church involvement in the political sphere and rejected the corporatism espoused by the Church. Bourassa opposed state intervention wherever possible and increasingly throughout his career emphasized the need for moral reform.[2]

As Levitt has shown, attitudes of historians, both Anglophone and Francophone, toward Bourassa consistently have been colored by the position of each historian on the major issues Bourassa addressed. Goldwin Smith, a fellow anti-imperialist, introduced him into historical literature in 1902. The isolationism of the 1930s and the biculturalism of the 1960s (Bourassa, while a champion of Francophone rights, always opposed separatism) occasioned favourable treatment among Anglophones, while Lionel Groulx, his onetime foe, described him as "l'incomparable Éveilleur." Bourassa's position on social issues - Catholic, moderately reformist, emphasizing the family and agricultural values - likewise has called forth praise and blame.[3]

Upon his death in Outremont, Quebec in 1952, Henri Bourassa was interred in Montreal's Cimetière Notre-Dame-des-Neiges.

Henri Bourassa Blvd., Henri-Bourassa metro station, and the federal riding of Bourassa, all in Montreal, are named for him. He is not related to Robert Bourassa, the former premier of Quebec.

Member contributor #47133515

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement