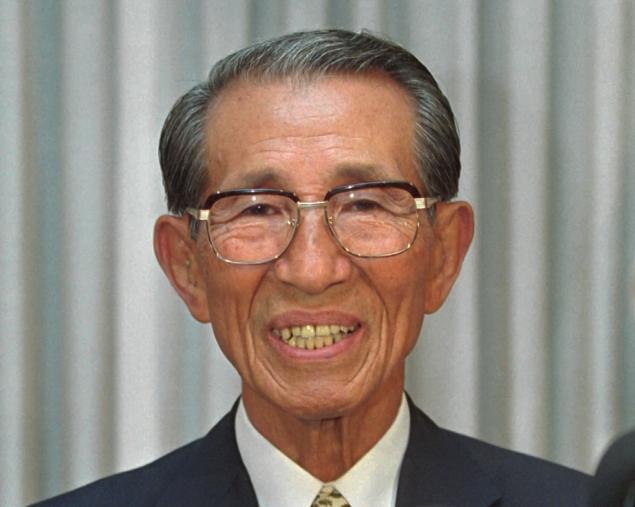

Tokyo (AFP) - A Japanese soldier who hid in the Philippine jungle for three decades, refusing to believe World War II was over until his former commander returned and ordered him to surrender, has died in Tokyo aged 91.

Hiroo Onoda waged a guerilla campaign in Lubang Island near Luzon until he was finally persuaded in 1974 that peace had broken out, ignoring leaflet drops and successive attempts to convince him the Imperial Army had been defeated.

He died in a Tokyo hospital on Thursday of heart failure.

Onoda was the last of several dozen so-called holdouts scattered around Asia, men who symbolised the astonishingly dogged perseverance of those called upon to fight for their emperor.

Their number included a soldier arrested in the jungles of Guam in 1972.

Trained as an intelligence officer and guerrilla tactics coach, Onoda was dispatched to Lubang in 1944 and ordered never to surrender, never to resort to suicidal attacks and to hold firm until reinforcements arrived.

He and three other soldiers continued to obey that order long after Japan's 1945 defeat.

Their existence became widely known in 1950, when one of their number emerged and returned to Japan.

The others continued to survey military facilities in the area, attacking local residents and occasionally fighting with Philippine forces, although one of them died soon afterwards.

Tokyo declared them dead after nine years of fruitless search.

However, in 1972, Onoda and the other surviving soldier got involved in a shoot-out with Philippine troops. His comrade died, but Onoda managed to escape.

The incident caused a sensation in Japan, which took his family members to Lubang in the hope of persuading him that hostilities were over.

Onoda later explained he had believed attempts to coax him out were the work of a puppet regime installed in Tokyo by the United States.

He read about his home country in newspapers that searchers deliberately scattered in the jungle for him to find, but dismissed their content as propaganda.

The regular overflight by US planes during the long years of the Vietnam war also convinced him that the battle he had joined was still being played out across Asia.

It was not until 1974, when his old commanding officer visited him in his jungle hideout to rescind the original order, that Onoda's War eventually ended.

Asked at a press conference in Japan after his return what he had been thinking about for the last 30 years, he told reporters: "Carrying out my orders."

But the Japan that Onoda returned to was much changed. The country he had left, and the one he had believed he was still fighting for, was in the grip of a militarist government, bent on realizing what it thought was its divine right to dominate the region.

Crippled by years of increasingly unsuccessful war, its economy was in ruins and its people were hungry.

But the Japan of 1974 was in the throes of a decades-long economic boom and in thrall to Western culture. It was also avowedly pacifist.

Onoda had difficultly adapting to the new reality and, in 1975, emigrated to Brazil to start a cattle ranch, although he continued to travel back and forth.

In 1984, still very much a celebrity, he established a youth camp, where he taught young Japanese some of the survival techniques he had used during his 30 years in hiding, when he lived on wild cows and bananas.

He returned to Lubang in 1996 on a visit, reportedly at the invitation of the local government, despite his having been involved in the killing of dozens of Filipinos during his three-decade battle.

He made a donation to the local community, which was reportedly used to set up a scholarship.

Late into his life, he enjoyed good health and boasted of a fine memory, honed by the need to remember the intelligence he had gathered.

Until recently, Onoda had been active in speaking engagements across Japan and in 2013 appeared on national broadcaster NHK.

"I lived through an era called a war. What people say varies from era to era," he told NHK last May.

"I think we should not be swayed by the climate of the time, but think calmly," he said.

His birth information. Onoda was born in March 1922 in Wakayama, western Japan, according to his organization. He was raised in a family with six siblings in a village near the ocean.

TOKYO (CNN) -

A Japanese soldier who hunkered down in the jungles of the Philippines for nearly three decades, refusing to believe that World War II had ended, has died in Tokyo. Hiroo Onoda was 91 years old.

In 1944, Onoda was sent to the small island of Lubang in the western Philippines to spy on U.S. forces in the area. Allied forces defeated the Japanese imperial army in the Philippines in the latter stages of the war, but Onoda, a lieutenant, evaded capture. While most of the Japanese troops on the island withdrew or surrendered in the face of oncoming American forces, Onoda and a few fellow holdouts hunkered down in the jungles, dismissing messages saying the war was over.

For 29 years, he survived on food gathered from the jungle or stolen from local farmers.

After losing his comrades to various circumstances, Onoda was eventually persuaded to come out of hiding in 1974.

His former commanding officer traveled to Lubang to see him and tell him he was released from his military duties.

In his battered old army uniform, Onoda handed over his sword, nearly 30 years after Japan surrendered..

"Every Japanese soldier was prepared for death, but as an intelligence officer I was ordered to conduct guerrilla warfare and not to die," Onoda told CNN affiliate, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. "I had to follow my orders as I was a soldier."

He returned to Japan, where he received a hero's welcome, a figure from a different era emerging into post-war modernity.

But anger remained in the Philippines, where he was blamed for multiple killings.

The Philippines government pardoned him. But when he returned to Lubang in 1996, relatives of people he was accused of killing gathered to demand compensation.

After his return to Japan, he moved to Brazil in 1975 and set up a cattle ranch.

"Japan's philosophy and ideas changed dramatically after World War II," Onoda told ABC. "That philosophy clashed with mine so I went to live in Brazil."

In 1984, he set up an organization, Onoda Shizenjyuku, to train young Japanese in the survival and camping skills he had acquired during his decades in Lubang's jungles.

His adventures are detailed in his book "No Surrender: My Thirty-year War." The Japan Times excerpted some of the book's highlights in 2007.

Here is a sample:

-- "Men should never compete with women. If they do, the guys will always lose. That is because women have a lot more endurance. My mother said that, and she was so right."

-- "If you have some thorns in your back, somebody needs to pull them out for you. We need buddies. The sense of belonging is born in the family and later includes friends, neighbors, community and country. That is why the idea of a nation is really important."

-- "Life is not fair and people are not equal. Some people eat better than others."

-- "Once you have burned your tongue on hot miso soup, you even blow on the cold sushi. This is how the Japanese government now behaves toward the U.S. and other nations."

Onoda was born in March 1922 in Wakayama, western Japan, according to his organization. He was raised in a family with six siblings in a village near the ocean.

Hiroyasu Miwa, a staff member of the organization that Onodo started in 1984, said Onodo died of pneumonia Thursday afternoon at St. Luke's Hospital in Tokyo. He had been sick since December.

Ever the faithful soldier, Onoda did not regret the time he had lost.

"I became an officer and I received an order," Onodo told ABC. "If I could not carry it out, I would feel shame. I am very competitive."

Copyright 2014 by CNN NewSource. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Tokyo (AFP) - A Japanese soldier who hid in the Philippine jungle for three decades, refusing to believe World War II was over until his former commander returned and ordered him to surrender, has died in Tokyo aged 91.

Hiroo Onoda waged a guerilla campaign in Lubang Island near Luzon until he was finally persuaded in 1974 that peace had broken out, ignoring leaflet drops and successive attempts to convince him the Imperial Army had been defeated.

He died in a Tokyo hospital on Thursday of heart failure.

Onoda was the last of several dozen so-called holdouts scattered around Asia, men who symbolised the astonishingly dogged perseverance of those called upon to fight for their emperor.

Their number included a soldier arrested in the jungles of Guam in 1972.

Trained as an intelligence officer and guerrilla tactics coach, Onoda was dispatched to Lubang in 1944 and ordered never to surrender, never to resort to suicidal attacks and to hold firm until reinforcements arrived.

He and three other soldiers continued to obey that order long after Japan's 1945 defeat.

Their existence became widely known in 1950, when one of their number emerged and returned to Japan.

The others continued to survey military facilities in the area, attacking local residents and occasionally fighting with Philippine forces, although one of them died soon afterwards.

Tokyo declared them dead after nine years of fruitless search.

However, in 1972, Onoda and the other surviving soldier got involved in a shoot-out with Philippine troops. His comrade died, but Onoda managed to escape.

The incident caused a sensation in Japan, which took his family members to Lubang in the hope of persuading him that hostilities were over.

Onoda later explained he had believed attempts to coax him out were the work of a puppet regime installed in Tokyo by the United States.

He read about his home country in newspapers that searchers deliberately scattered in the jungle for him to find, but dismissed their content as propaganda.

The regular overflight by US planes during the long years of the Vietnam war also convinced him that the battle he had joined was still being played out across Asia.

It was not until 1974, when his old commanding officer visited him in his jungle hideout to rescind the original order, that Onoda's War eventually ended.

Asked at a press conference in Japan after his return what he had been thinking about for the last 30 years, he told reporters: "Carrying out my orders."

But the Japan that Onoda returned to was much changed. The country he had left, and the one he had believed he was still fighting for, was in the grip of a militarist government, bent on realizing what it thought was its divine right to dominate the region.

Crippled by years of increasingly unsuccessful war, its economy was in ruins and its people were hungry.

But the Japan of 1974 was in the throes of a decades-long economic boom and in thrall to Western culture. It was also avowedly pacifist.

Onoda had difficultly adapting to the new reality and, in 1975, emigrated to Brazil to start a cattle ranch, although he continued to travel back and forth.

In 1984, still very much a celebrity, he established a youth camp, where he taught young Japanese some of the survival techniques he had used during his 30 years in hiding, when he lived on wild cows and bananas.

He returned to Lubang in 1996 on a visit, reportedly at the invitation of the local government, despite his having been involved in the killing of dozens of Filipinos during his three-decade battle.

He made a donation to the local community, which was reportedly used to set up a scholarship.

Late into his life, he enjoyed good health and boasted of a fine memory, honed by the need to remember the intelligence he had gathered.

Until recently, Onoda had been active in speaking engagements across Japan and in 2013 appeared on national broadcaster NHK.

"I lived through an era called a war. What people say varies from era to era," he told NHK last May.

"I think we should not be swayed by the climate of the time, but think calmly," he said.

His birth information. Onoda was born in March 1922 in Wakayama, western Japan, according to his organization. He was raised in a family with six siblings in a village near the ocean.

TOKYO (CNN) -

A Japanese soldier who hunkered down in the jungles of the Philippines for nearly three decades, refusing to believe that World War II had ended, has died in Tokyo. Hiroo Onoda was 91 years old.

In 1944, Onoda was sent to the small island of Lubang in the western Philippines to spy on U.S. forces in the area. Allied forces defeated the Japanese imperial army in the Philippines in the latter stages of the war, but Onoda, a lieutenant, evaded capture. While most of the Japanese troops on the island withdrew or surrendered in the face of oncoming American forces, Onoda and a few fellow holdouts hunkered down in the jungles, dismissing messages saying the war was over.

For 29 years, he survived on food gathered from the jungle or stolen from local farmers.

After losing his comrades to various circumstances, Onoda was eventually persuaded to come out of hiding in 1974.

His former commanding officer traveled to Lubang to see him and tell him he was released from his military duties.

In his battered old army uniform, Onoda handed over his sword, nearly 30 years after Japan surrendered..

"Every Japanese soldier was prepared for death, but as an intelligence officer I was ordered to conduct guerrilla warfare and not to die," Onoda told CNN affiliate, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. "I had to follow my orders as I was a soldier."

He returned to Japan, where he received a hero's welcome, a figure from a different era emerging into post-war modernity.

But anger remained in the Philippines, where he was blamed for multiple killings.

The Philippines government pardoned him. But when he returned to Lubang in 1996, relatives of people he was accused of killing gathered to demand compensation.

After his return to Japan, he moved to Brazil in 1975 and set up a cattle ranch.

"Japan's philosophy and ideas changed dramatically after World War II," Onoda told ABC. "That philosophy clashed with mine so I went to live in Brazil."

In 1984, he set up an organization, Onoda Shizenjyuku, to train young Japanese in the survival and camping skills he had acquired during his decades in Lubang's jungles.

His adventures are detailed in his book "No Surrender: My Thirty-year War." The Japan Times excerpted some of the book's highlights in 2007.

Here is a sample:

-- "Men should never compete with women. If they do, the guys will always lose. That is because women have a lot more endurance. My mother said that, and she was so right."

-- "If you have some thorns in your back, somebody needs to pull them out for you. We need buddies. The sense of belonging is born in the family and later includes friends, neighbors, community and country. That is why the idea of a nation is really important."

-- "Life is not fair and people are not equal. Some people eat better than others."

-- "Once you have burned your tongue on hot miso soup, you even blow on the cold sushi. This is how the Japanese government now behaves toward the U.S. and other nations."

Onoda was born in March 1922 in Wakayama, western Japan, according to his organization. He was raised in a family with six siblings in a village near the ocean.

Hiroyasu Miwa, a staff member of the organization that Onodo started in 1984, said Onodo died of pneumonia Thursday afternoon at St. Luke's Hospital in Tokyo. He had been sick since December.

Ever the faithful soldier, Onoda did not regret the time he had lost.

"I became an officer and I received an order," Onodo told ABC. "If I could not carry it out, I would feel shame. I am very competitive."

Copyright 2014 by CNN NewSource. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Records on Ancestry

Advertisement